Batman

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Batman | |

Second printing cover of Batman #608 (Oct. 2002). Pencils by Jim Lee and inks by Scott Williams. |

|

| Publication information | |

|---|---|

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| First appearance | Detective Comics #27 (May 1939). |

| Created by | Bob Kane (concept) Bill Finger (uncredited) |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Bruce Wayne |

| Team affiliations | Batman Family Justice League Wayne Enterprises Outsiders |

| Partnerships | Robin |

| Notable aliases | Matches Malone |

Batman (originally referred to as the Bat-Man and still referred to at times as the Batman) is a fictional character, a comic book superhero co-created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger (although only Kane receives official credit), appearing in publications by DC Comics. The character first appeared in Detective Comics #27 in May 1939. Batman's secret identity is Bruce Wayne, a wealthy industrialist, playboy, and philanthropist. Witnessing the murder of his parents as a child, Wayne trains himself both physically and intellectually and dons a bat-themed costume in order to fight crime.[1] Batman operates in the fictional American Gotham City, assisted by various supporting characters including his sidekick Robin and his butler Alfred Pennyworth, and fights an assortment of villains influenced by the characters' roots in film and pulp magazines. Unlike most superheroes, he does not possess any superpowers; he makes use of intellect, detective skills, science and technology, wealth, physical prowess, and intimidation in his war on crime.

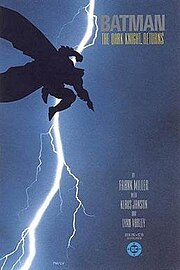

Batman became a popular character soon after his introduction, and gained his own comic book title, Batman, in 1940. As the decades wore on, differing takes on the character emerged. The late 1960s Batman television series utilized a camp aesthetic associated with the character for years after the show ended. Various creators worked to return the character to his dark roots, culminating in the 1986 miniseries Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, by writer-artist Frank Miller. The successes of director Tim Burton's 1989 film Batman and Christopher Nolan's 2005 reboot Batman Begins also helped to reignite popular interest in the character.[2] A cultural icon, Batman has been licensed and adapted into a variety of media, from radio to television and film, and appears on a variety of merchandise sold all over the world.

Contents |

Publication history

Creation

In early 1938, the success of Superman in Action Comics prompted editors at the comic book division of National Publications (the future DC Comics) to request more superheroes for its titles. In response, Bob Kane created "the Bat-Man".[3] Collaborator Bill Finger recalled Kane

| “ | ...had an idea for a character called 'Batman', and he'd like me to see the drawings. I went over to Kane's, and he had drawn a character who looked very much like Superman with kind of ... reddish tights, I believe, with boots ... no gloves, no gauntlets ... with a small domino mask, swinging on a rope. He had two stiff wings that were sticking out, looking like bat wings. And under it was a big sign ... BATMAN.[4] | ” |

Finger offered such suggestions as giving the character a cowl instead of a simple domino mask, a cape instead of wings, and gloves, and removing the red sections from the original costume.[5][6] Finger said he devised the name Bruce Wayne for the character's secret identity: "Bruce Wayne's first name came from Robert Bruce, the Scottish patriot. Wayne, being a playboy, was a man of gentry. I searched for a name that would suggest colonialism. I tried Adams, Hancock ... then I thought of Mad Anthony Wayne".[7]

Various aspects of Batman's personality, character history, visual design and equipment were inspired by contemporary popular culture of the 1930s, including movies, pulp magazines, comic strips, newspaper headlines, and even aspects of Kane himself.[8] Kane noted especially the influence of the films The Mark of Zorro (1920) and The Bat Whispers (1930) in the creation of the iconography associated with the character, while Finger drew inspiration from literary characters Doc Savage, The Shadow, and Sherlock Holmes in his depiction of Batman as a master sleuth and scientist.[9]

Kane, in his 1989 autobiography, detailed Finger's contributions to Batman's creation:

| “ | One day I called Bill and said, 'I have a new character called the Bat-Man and I've made some crude, elementary sketches I'd like you to look at'. He came over and I showed him the drawings. At the time, I only had a small domino mask, like the one Robin later wore, on Batman's face. Bill said, 'Why not make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him, and take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious?' At this point, the Bat-Man wore a red union suit; the wings, trunks, and mask were black. I thought that red and black would be a good combination. Bill said that the costume was too bright: 'Color it dark gray to make it look more ominous'. The cape looked like two stiff bat wings attached to his arms. As Bill and I talked, we realized that these wings would get cumbersome when Bat-Man was in action, and changed them into a cape, scalloped to look like bat wings when he was fighting or swinging down on a rope. Also, he didn't have any gloves on, and we added them so that he wouldn't leave fingerprints.[10] | ” |

Kane signed away ownership in the character in exchange for, among other compensation, a mandatory byline on all Batman comics. This byline did not, originally, say "Batman created by Bob Kane"; his name was simply written on the title page of each story. The name disappeared from the comic book in the mid-1960s, replaced by credits for each story's actual writer and artists. In the late 1970s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster began receiving a "created by" credit on the Superman titles, along with William Moulton Marston being given the byline for creating Wonder Woman, Batman stories began saying "Created by Bob Kane" in addition to the other credits.

Finger did not receive the same recognition. While he had received credit for other DC work since the 1940s, he began, in the 1960s, to receive limited acknowledgment for his Batman writing; in the letters page of Batman #169 (Feb. 1965) for example, editor Julius Schwartz names him as the creator of the Riddler, one of Batman's recurring villains. However, Finger's contract left him only with his writing page rate and no byline. Kane wrote, "Bill was disheartened by the lack of major accomplishments in his career. He felt that he had not used his creative potential to its fullest and that success had passed him by".[7] At the time of Finger's death in 1974, DC had not officially credited Finger as Batman co-creator.

Jerry Robinson, who also worked with Finger and Kane on the strip at this time, has criticized Kane for failing to share the credit. He recalled Finger resenting his position, stating in a 2005 interview with The Comics Journal:

| “ | Bob made him more insecure, because while he slaved working on Batman, he wasn't sharing in any of the glory or the money that Bob began to make, which is why... [he was] going to leave [Kane's employ]. ... [Kane] should have credited Bill as co-creator, because I know; I was there. ... That was one thing I would never forgive Bob for, was not to take care of Bill or recognize his vital role in the creation of Batman. As with Siegel and Shuster, it should have been the same, the same co-creator credit in the strip, writer and artist.[11] | ” |

Although Kane initially rebutted Finger's claims at having created the character, writing in a 1965 open letter to fans that "it seemed to me that Bill Finger has given out the impression that he and not myself created the ''Batman, t' [sic] as well as Robin and all the other leading villains and characters. This statement is fraudulent and entirely untrue." Kane himself also commented on Finger's lack of credit. "The trouble with being a 'ghost' writer or artist is that you must remain rather anonymously without 'credit'. However, if one wants the 'credit', then one has to cease being a 'ghost' or follower and become a leader or innovator".[12]

In 1989, Kane revisited Finger's situation, recalling in an interview,

| “ | In those days it was like, one artist and he had his name over it [the comic strip] — the policy of DC in the comic books was, if you can't write it, obtain other writers, but their names would never appear on the comic book in the finished version. So Bill never asked me for it [the byline] and I never volunteered — I guess my ego at that time. And I felt badly, really, when he [Finger] died.[13] | ” |

Early years

The first Batman story, "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate," was published in Detective Comics #27 (May 1939). Finger said, "Batman was originally written in the style of the pulps",[14] and this influence was evident with Batman showing little remorse over killing or maiming criminals and was not above using firearms. Batman proved a hit character, and he received his own solo title in 1940, while continuing to star in Detective Comics. By that time, National was the top-selling and most influential publisher in the industry; Batman and the company's other major hero, Superman, were the cornerstones of the company's success.[15] The two characters were featured side-by-side as the stars of World's Finest Comics, which was originally titled World's Best Comics when it debuted in fall 1940. Creators including Jerry Robinson and Dick Sprang also worked on the strips during this period.

Over the course of the first few Batman strips elements were added to the character and the artistic depiction of Batman evolved. Kane noted that within six issues he drew the character's jawline more pronounced, and lengthened the ears on the costume. "About a year later he was almost the full figure, my mature Batman," Kane said.[16] Batman's characteristic utility belt was introduced in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939), followed by the boomerang-like batarang and the first bat-themed vehicle in #31 (Sept. 1939). The character's origin was revealed in #33 (Nov. 1939), unfolding in a two-page story that establishes the brooding persona of Batman, a character driven by the loss of his parents. Written by Finger, it depicts a young Bruce Wayne witnessing the death of his parents as part of a street robbery. Days later, at their grave, the child vows that "by the spirits of my parents [I will] avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals".[17][18][19]

The early, pulp-inflected portrayal of Batman started to soften in Detective Comics #38 (April 1940) with the introduction of Robin, Batman's kid sidekick.[20] Robin was introduced, based on Finger's suggestion Batman needed a "Watson" with whom Batman could talk.[21] Sales nearly doubled, despite Kane's preference for a solo Batman, and it sparked a proliferation of "kid sidekicks".[22] The first issue of the solo spin-off series Batman was notable not only for introducing two of his most persistent antagonists, the Joker and Catwoman, but for a story in which Batman shoots some monstrous giants to death. That story prompted editor Whitney Ellsworth to decree that the character could no longer kill or use a gun.[23]

By 1942, the writers and artists behind the Batman comics had established most of the basic elements of the Batman mythos.[24] In the years following World War II, DC Comics "adopted a postwar editorial direction that increasingly de-emphasized social commentary in favor of lighthearted juvenile fantasy." The impact of this editorial approach was evident in Batman comics of the postwar period; removed from the "bleak and menacing world" of the strips of the early 1940s, Batman was instead portrayed as a respectable citizen and paternal figure that inhabited a "bright and colorful" environment.[25]

The 1950s and early 1960s

Batman was one of the few superhero characters to be continuously published as interest in the genre waned during the 1950s. In the story "The Mightiest Team in the World" in Superman #76 (June 1952), Batman teams up with Superman for the first time and the pair discovers each other's secret identity.[26] Following the success of this story, World's Finest Comics was revamped so it featured stories starring both heroes together, instead of the separate Batman and Superman features that had been running before.[27] The team-up of the characters was "a financial success in an era when those were few and far between;"[28] this series of stories ran until the book's cancellation in 1986.

Batman comics were among those criticized when the comic book industry came under scrutiny with the publication of psychologist Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent in 1954. Wertham's thesis was that children imitated crimes committed in comic books, and that these works corrupt the morals of the youth. Wertham criticized Batman comics for their supposed homosexual overtones and argued that Batman and Robin were portrayed as lovers.[29] Wertham's criticisms raised a public outcry during the 1950s, eventually leading to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority. The tendency towards a "sunnier Batman" in the postwar years intensified after the introduction of the Comics Code.[30] It has also been suggested by scholars that the characters of Batwoman (in 1956) and Bat-Girl (in 1961) were introduced in part to refute the allegation that Batman and Robin were gay, and the stories took on a campier, lighter feel.[31]

In the late 1950s Batman stories gradually become more science fiction-oriented, an attempt at mimicking the success of other DC characters that had dabbled in the genre.[32] New characters such as Batwoman, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were introduced. Batman's adventures often involved odd transformations or bizarre space aliens. In 1960, Batman debuted as a member of the Justice League of America in The Brave and the Bold #28 (February 1960), and went on to appear in several Justice League comic series starting later that same year.

"New Look" Batman and camp

By 1964, sales on Batman titles had fallen drastically. Bob Kane noted that, as a result, DC was "planning to kill Batman off altogether."[33] In response to this, editor Julius Schwartz was assigned to the Batman titles. He presided over drastic changes, beginning with 1964's Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), which was cover-billed as the "New Look". Schwartz introduced changes designed to make Batman more contemporary, and to return him to more detective-oriented stories. He brought in artist Carmine Infantino to help overhaul the character. The Batmobile was redesigned, and Batman's costume was modified to incorporate a yellow ellipse behind the bat-insignia. The space aliens and characters of the 1950s such as Batwoman, Ace, and Bat-Mite were retired. Batman's butler Alfred was killed off, and replaced with Aunt Harriet, who came to live with Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson.[34]

The debut of the Batman television series in 1966 had a profound influence on the character. The success of the series increased sales throughout the comic book industry, and Batman reached a circulation of close to 900,000 copies.[36] Elements such as the character of Batgirl and the show's campy nature were introduced into the comics; the series also initiated the return of Alfred. Although both the comics and TV show were successful for a time, the camp approach eventually wore thin and the show was canceled in 1968. In the aftermath, the Batman comics themselves lost popularity once again. As Julius Schwartz noted, "When the television show was a success, I was asked to be campy, and of course when the show faded, so did the comic books."[37]

Starting in 1969, writer Dennis O'Neil and artist Neal Adams made a deliberate effort to distance Batman from the campy portrayal of the 1960s TV series and to return the character to his roots as a "grim avenger of the night".[38] O'Neil said his idea was "simply to take it back to where it started. I went to the DC library and read some of the early stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane and Finger were after".[39]

O'Neil and Adams first collaborated on the story "The Secret of the Waiting Graves" (Detective Comics #395, Jan. 1970). Few stories were true collaborations between O'Neil, Adams, Schwartz, and inker Dick Giordano, and in actuality these men were mixed and matched with various other creators during the 1970s; nevertheless the influence of their work was "tremendous".[40] Giordano said: "We went back to a grimmer, darker Batman, and I think that's why these stories did so well . . . Even today we're still using Neal's Batman with the long flowing cape and the pointy ears."[41] While the work of O'Neil and Adams was popular with fans, the acclaim did little to help declining sales; the same held true with a similarly acclaimed run by writer Steve Englehart and penciler Marshall Rogers in Detective Comics #471-476 (Aug. 1977 - April 1978), which went on to influence the 1989 movie Batman and be adapted for Batman: The Animated Series, which debuted in 1992.[42] Regardless, circulation continued to drop through the 1970s and 1980s, hitting an all-time low in 1985.[43]

The Dark Knight Returns and later

Frank Miller's 1986 limited series Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, which tells the story of a 50 year old Batman coming out of retirement in a possible future, reinvigorated the character. The Dark Knight Returns was a financial success and has since become one of the medium's most noted touchstones.[44] The series also sparked a major resurgence in the character's popularity.[45]

That year Dennis O'Neil took over as editor of the Batman titles and set the template for the portrayal of Batman following DC's status quo-altering miniseries Crisis on Infinite Earths. O'Neil operated under the assumption that he was hired to revamp the character and as a result tried to instill a different tone in the books than had gone before.[46] One outcome of this new approach was the "Year One" storyline in Batman #404-407 (Feb.-May 1987), in which Frank Miller and artist David Mazzucchelli redefined the character's origins. Writer Alan Moore and artist Brian Bolland continued this dark trend with 1988's 48-page one-shot Batman: The Killing Joke, in which the Joker, attempting to drive Commissioner Gordon insane, cripples Gordon's daughter Barbara, and then kidnaps and tortures the commissioner, physically and psychologically.

The Batman comics garnered major attention in 1988 when DC Comics created a 900 number for readers to call to vote on whether Jason Todd, the second Robin, lived or died. Voters decided in favor of Jason's death by a narrow margin of 28 votes (see Batman: A Death in the Family).[47] The following year saw the release of Tim Burton's Batman feature film, which firmly brought the character back to the public's attention, grossing millions of dollars at the box office, and millions more in merchandising. In the same year, the first issue of Legends of the Dark Knight, the first new solo Batman title in nearly fifty years, sold close to a million copies.[48]

The 1993 "Knightfall" story arc introduced a new villain, Bane, who critically injures Bruce Wayne. Jean-Paul Valley, known as Azrael, is called upon to wear the Batsuit during Wayne's convalescence. Writers Doug Moench, Chuck Dixon, and Alan Grant worked on the Batman titles during "Knightfall", and would also contribute to other Batman crossovers throughout the 1990s. 1998's "Cataclysm" storyline served as the precursor to 1999's "No Man's Land", a year-long storyline that ran through all the Batman-related titles dealing with the effects of an earthquake-ravaged Gotham City. At the conclusion of "No Man's Land", O'Neil stepped down as editor and was replaced by Bob Schreck.

In 2003, writer Jeph Loeb and artist Jim Lee began "Batman: Hush", a 12-issue run on Batman that introduced a new villain, Hush, which guest-starred every major supporting character and Batman villain, and laid the groundwork for the return of Jason Todd. Lee's first regular comic book work in nearly a decade, the series became #1 on the Diamond Comic Distributors sales chart for the first time since Batman #500 (Oct. 1993). Lee then teamed with Frank Miller on All-Star Batman and Robin, which debuted with the best-selling issue in 2005,[49] as well as the highest sales in the industry since 2003.[50] Starting in 2006, the regular writers on Batman and Detective Comics were Grant Morrison and Paul Dini, respectively. Batman is on hiatus during the months of March, April, and May 2009 as the status quo is changed in the miniseries Batman: Battle for the Cowl. In June 2009, Judd Winick is to return to writing Batman and Greg Rucka is to return to writing Detective Comics.

Fictional character history

Batman's history has undergone various revisions, both minor and major. Few elements of the character's history have remained constant. Scholars William Uricchio and Roberta E. Pearson noted in the early 1990s, "Unlike some fictional characters, the Batman has no primary urtext set in a specific period, but has rather existed in a plethora of equally valid texts constantly appearing over more than five decades."[51]

The central fixed event in the Batman stories is the character's origin story.[52] As a little boy, Bruce Wayne is horrified and traumatized to see his parents, the physician Dr. Thomas Wayne and his wife Martha, being murdered by a mugger in front of his very eyes. This drives him to fight crime in Gotham City as Batman. Pearson and Uricchio also noted beyond the origin story and such events as the introduction of Robin, "Until recently, the fixed and accruing and hence, canonized, events have been few in number,"[52] a situation altered by an increased effort by later Batman editors such as Dennis O'Neil to ensure consistency and continuity between stories.[53]

Golden Age

In Batman's first appearance in Detective Comics #27, he is already operating as a crime fighter.[54] Batman's origin is first presented in Detective Comics #33 in November 1939, and is later fleshed out in Batman #47. As these comics state, Bruce Wayne is born to Dr. Thomas Wayne and his wife Martha, two very wealthy and charitable Gotham City socialites. Bruce is brought up in Wayne Manor, with its wealthy splendor, and leads a happy and privileged existence until the age of eight, when his parents are killed by a small-time criminal named Joe Chill while on their way home from a movie theater. Bruce Wayne swears an oath to rid the city of the evil that had taken his parents' lives. He engages in intense intellectual and physical training; however, he realizes that these skills alone would not be enough. "Criminals are a superstitious and cowardly lot", Wayne remarks, "so my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts. I must be a creature of the night, black, terrible..." As if responding to his desires, a bat suddenly flies through the window, inspiring Bruce to assume the persona of Batman.[55]

In early strips, Batman's career as a vigilante earns him the ire of the police. During this period Wayne has a fiancée named Julie Madison.[56] Wayne takes in an orphaned circus acrobat, Dick Grayson, who becomes his sidekick, Robin. Batman also becomes a founding member of the Justice Society of America,[57] although he, like Superman, is an honorary member,[58] and thus only participates occasionally. Batman's relationship with the law thaws quickly, and he is made an honorary member of Gotham City's police department.[59] During this time, butler Alfred Pennyworth arrives at Wayne Manor, and after deducing the Dynamic Duo's secret identities joins their service.[60]

Silver Age

The Silver Age of comic books in DC Comics is sometimes held to have begun in 1956 when the publisher introduced Barry Allen as a new, updated version of The Flash. Batman is not significantly changed by the late 1950s for the continuity which would be later referred to as Earth-One. The lighter tone Batman had taken in the period between the Golden and Silver Ages led to the stories of the late 1950s and early 1960s that often feature a large number of science-fiction elements, and Batman is not significantly updated in the manner of other characters until Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), in which Batman reverts to his detective roots, with most science-fiction elements jettisoned from the series.

After the introduction of DC Comics' multiverse in the 1960s, DC established that stories from the Golden Age star the Earth-Two Batman, a character from a parallel world. This version of Batman partners with and marries the reformed Earth-Two Catwoman, Selina Kyle (as shown in Superman Family #211) and fathers Helena Wayne, who, as the Huntress, becomes (along with the Earth-Two Robin) Gotham's protector once Wayne retires from the position to become police commissioner, a position he occupies until he is killed during one final adventure as Batman. Batman titles however often ignored that a distinction had been made between the pre-revamp and post-revamp Batmen (since unlike The Flash or Green Lantern, Batman comics had been published without interruption through the 1950s) and would on occasion make reference to stories from the Golden Age.[61] Nevertheless, details of Batman's history were altered or expanded upon through the decades. Additions include meetings with a future Superman during his youth, his upbringing by his uncle Philip Wayne (introduced in Batman #208, Jan./Feb. 1969) after his parents' death, and appearances of his father and himself as prototypical versions of Batman and Robin, respectively.[62][63] In 1980 then-editor Paul Levitz commissioned the Untold Legend of the Batman limited series to thoroughly chronicle Batman's origin and history.

Batman meets and regularly works with other heroes during the Silver Age, most notably Superman, whom he began regularly working alongside in a series of team-ups in World's Finest Comics, starting in 1954 and continuing through the series' cancellation in 1986. Batman and Superman are usually depicted as close friends. Batman becomes a founding member of the Justice League of America, appearing in its first story in 1960s Brave and the Bold #28. In the 1970s and 1980s, Brave and the Bold became a Batman title, in which Batman teams up with a different DC Universe superhero each month.

In 1969, Dick Grayson attends college as part of DC Comics' effort to revise the Batman comics. Additionally, Batman also moves from Wayne Manor into a penthouse apartment atop the Wayne Foundation building in downtown Gotham City, in order to be closer to Gotham City's crime. Batman spends the 1970s and early 1980s mainly working solo, with occasional team-ups with Robin and/or Batgirl. Batman's adventures also become somewhat darker and more grim during this period, depicting increasingly violent crimes, including the first appearance (since the early Golden Age) of the Joker as a homicidal psychopath, and the arrival of Ra's al Ghul, a centuries-old terrorist who knows Batman's secret identity. In the 1980s, Dick Grayson becomes Nightwing.[1]

In the final issue of Brave and the Bold in 1983, Batman quits the Justice League and forms a new group called the Outsiders. He serves as the team's leader until Batman and the Outsiders #32 (1986) and the comic subsequently changed its title.

Modern Batman

After the 12-issue limited series Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC Comics rebooted the histories of some major characters in an attempt at updating them for contemporary audiences. Frank Miller retold Batman's origin in the storyline Year One from Batman #404-407, which emphasizes a grittier tone in the character.[64] Though the Earth-Two Batman is erased from history, many stories of Batman's Silver Age/Earth-One career (along with an amount of Golden Age ones) remain canonical in the post-Crisis universe, with his origins remaining the same in essence, despite alteration. For example, Gotham's police are mostly corrupt, setting up further need for Batman's existence. While Dick Grayson's past remains much the same, the history of Jason Todd, the second Robin, is altered, turning the boy into the orphan son of a petty crook, who tries to steal the tires from the Batmobile.[65] Also removed is the guardian Phillip Wayne, leaving young Bruce to be raised by Alfred. Additionally, Batman is no longer a founding member of the Justice League of America, although he becomes leader for a short time of a new incarnation of the team launched in 1987. To help fill in the revised backstory for Batman following Crisis, DC launched a new Batman title called Legends of the Dark Knight in 1989 and has published various miniseries and one-shot stories since then that largely take place during the "Year One" period. Various stories from Jeph Loeb and Matt Wagner also touch upon this era.

In 1988's "Batman: A Death in the Family" storyline from Batman #426-429 Jason Todd, the second Robin, is killed by the Joker.[1] Subsequently Batman begins exhibiting an excessive, reckless approach to his crime fighting, a result of the pain of losing Jason Todd. Batman works solo until the decade's close, when Tim Drake becomes the new Robin.[66] In 2005 writers resurrected the Jason Todd character and have pitted him against his former mentor.

Many of the major Batman storylines since the 1990s have been inter-title crossovers that run for a number of issues. In 1993 DC published both the "Death of Superman" storyline and "Knightfall" . In the Knightfall storyline's first phase, the new villain Bane paralyzes Batman, leading Wayne to ask Azrael to take on the role. After the end of "Knightfall", the storylines split in two directions, following both the Azrael-Batman's adventures, and Bruce Wayne's quest to become Batman once more. The story arcs realign in "KnightsEnd", as Azrael becomes increasingly violent and is defeated by a healed Bruce Wayne. Wayne hands the Batman mantle to Dick Grayson (then Nightwing) for an interim period, while Wayne trains to return to his role as Batman.[67]

The 1994 company-wide crossover Zero Hour changes aspects of DC continuity again, including those of Batman. Noteworthy among these changes is that the general populace and the criminal element now considers Batman an urban legend rather than a known force. Similarly, the Waynes' killer is never caught or identified, effectively removing Joe Chill from the new continuity, rendering stories such as "Year Two" non-canon.

Batman once again becomes a member of the Justice League during Grant Morrison's 1996 relaunch of the series, titled JLA. While Batman contributes greatly to many of the team's successes, the Justice League is largely uninvolved as Batman and Gotham City face catastrophe in the decade's closing crossover arc. In 1998's "Cataclysm" storyline, Gotham City is devastated by an earthquake. Deprived of many of his technological resources, Batman fights to reclaim the city from legions of gangs during 1999's "No Man's Land." While Lex Luthor rebuilds Gotham at the end of the "No Man's Land" storyline, he then frames Bruce Wayne for murder in the "Bruce Wayne: Murderer?" and "Bruce Wayne: Fugitive" story arcs; Wayne is eventually acquitted.

DC's 2005 limited series Identity Crisis, reveals that JLA member Zatanna had edited Batman's memories, leading to his deep loss of trust in the rest of the superhero community. Batman later creates the Brother I satellite surveillance system to watch over the other heroes. Its eventual co-opting by Maxwell Lord is one of the main events that leads to the Infinite Crisis miniseries, which again restructures DC continuity. In Infinite Crisis #7, Alexander Luthor, Jr. mentions that in the newly rewritten history of the "New Earth", created in the previous issue, the murderer of Martha and Thomas Wayne – again, Joe Chill – was captured, thus undoing the retcon created after Zero Hour. Batman and a team of superheroes destroy Brother Eye and the OMACs.

Following Infinite Crisis, Bruce Wayne, Dick Grayson, and Tim Drake retrace the steps Bruce had taken when he originally left Gotham City, to "rebuild Batman".[citation needed] In the "Face the Face" storyline, Batman and Robin return to Gotham City after their year-long absence. Part of this absence is captured in during Week 30 of the 52 series, which shows Batman fighting his inner demons.[68] Later on in 52, Batman is shown undergoing an intense meditation ritual in Nanda Parbat. This becomes an important part of the regular Batman title, which reveals that Batman was reborn as a more effective crime fighter while undergoing this ritual, having "hunted down and ate" the last traces of fear in his mind.[69][70]

At the end of the "Face the Face" story arc, Bruce adopts Tim as his son.[71] The follow-up story arc in Batman, "Batman & Son", introduces Damian Wayne, who is Batman's son with Talia al Ghul. Batman, along with Superman and Wonder Woman, reforms the Justice League in the new Justice League of America series,[72] and is leading the newest incarnation of the Outsiders.[73]

Grant Morrison's 2008 storyline, "Batman R.I.P.", featuring Batman being physically and mentally broken by the enigmatic "Black Glove", garnered much news coverage in advance of its highly-promoted conclusion, which would supposedly feature the death of Bruce Wayne.[74][75] The original intention was, in fact, not for Batman to die in the pages of "R.I.P.", but for the story to continue with the current DC event Final Crisis and have the death occur there. However, out of desire to give the storyline of "R.I.P." a suitable conclusion in and of itself, Batman appeared to die in the final chapter of the story[76] only to turn up alive in the very next issue as a prisoner of the "Crisis" villain, Darkseid. The death came a month later in the limited series Final Crisis, during which Batman confronts Darkseid. Making a rare exception, Batman uses a gun loaded with a Radion (which is poisonous to the New Gods) bullet to shoot Darkseid's shoulder just as Darkseid unleashes his Omega Sanction, the "life that is death", upon Batman.[77] However, the Omega Sanction does not actually kill its victims: instead, it sends their consciousness travelling through parallel worlds, and at the conclusion of Final Crisis it is made clear that this is the fate that has befallen the still-living Batman as he watches the passing of Anthro in the distant past.[78]

Characterization

Batman's primary character traits can be summarized as "wealth; physical prowess; deductive abilities and obsession".[52] The details and tone of Batman's characterization have varied over the years due to different interpretations. Dennis O'Neil noted that character consistency was not a major concern during early editorial regimes: "Julie Schwartz did a Batman in Batman and Detective and Murray Boltinoff did a Batman in the Brave and the Bold and apart from the costume they bore very little resemblance to each other. Julie and Murray did not coordinate their efforts, did not pretend to, did not want to, were not asked to. Continuity was not important in those days".[79]

A main component that defines Batman as a character is his origin story. Bob Kane said he and Bill Finger discussed the character's background and decided that "there's nothing more traumatic than having your parents murdered before your eyes."[80] Batman is thus driven to fight crime, sometimes employing illegal and morally dubious tactics (like torture and intrusive surveillance), in order to avenge the death of his parents.[52] While details of Batman's origin have varied from version to version, the "reiteration of the basic origin events holds together otherwise divergent expressions" of the character.[81] The origin is the source of many of the character's traits and attributes, which play out in many of the character's adventures.[52]

Batman is often treated as a vigilante by other characters in his stories. Frank Miller views the character as "a dionysian figure, a force for anarchy that imposes an individual order."[82] Dressed as a bat, Batman deliberately cultivates a frightening persona in order to aid him in crime fighting.[83]

Bruce Wayne

In his secret identity, Batman is Bruce Wayne, a wealthy businessman who lives in Gotham City. To the world at large, Bruce Wayne is often seen as an irresponsible, superficial playboy who lives off his family's personal fortune (amassed when Bruce's family invested in Gotham real estate before the city was a bustling metropolis)[84] and the profits of Wayne Enterprises, a major private technology firm that he inherits. However, Wayne is also known for his contributions to charity, notably through his Wayne Foundation.[85] Bruce creates the playboy public persona to aid in throwing off suspicion of his secret identity, often acting dim-witted and self-absorbed to further the act.[86]

Writers of both Batman and Superman stories have often compared the two within the context of various stories, to varying conclusions. Like Superman, the prominent persona of Batman's dual identities varies with time. Modern-age comics have tended to portray "Bruce Wayne" as the facade, with "Batman" as the truer representation of his personality[87] (in counterpoint to the post-Crisis Superman, whose "Clark Kent" persona is the 'real' personality, and "Superman" is the 'mask'[88][89]).

Skills, abilities, and resources

Unlike many superheroes, Batman has no superpowers and instead relies on "his own scientific knowledge, detective skills, and athletic prowess."[20] In the stories Batman is regarded as one of the world's greatest detectives.[90] In Grant Morrison's first storyline in JLA, Superman describes Batman as "the most dangerous man on Earth," able to defeat a team of superpowered aliens all by himself in order to rescue his imprisoned teammates.[91] He is also a master of disguise, often gathering information under the identity of Matches Malone.

Costume

Batman's costume incorporates the imagery of a bat in order to frighten criminals.[92][93][94] The details of the Batman costume change repeatedly through various stories and media, but the most distinctive elements remain consistent: a scallop-hem cape, a cowl covering most of the face featuring a pair of batlike ears, and a stylized bat emblem on the chest, plus the ever-present utility belt. The costumes' colors are traditionally blue and grey,[93][95][96][97] although this colorization arose due to the way comic book art is colored.[93] Finger and Kane conceptualized Batman as having a black cape and cowl and grey suit, but conventions in coloring called for black to be highlighted with blue.[93] This coloring has been claimed by Larry Ford, in Place, Power, Situation, and Spectacle: A Geography of Film, to be a reversion of conventional color-coding symbolism, which sees "bad guys" wearing dark colors.[98] Batman's gloves typically feature three scallops that protrude from long, gauntlet-like cuffs, although in his earliest appearances he wore short, plain gloves without the scallops. A yellow ellipse around the bat logo on the character's chest was added in 1964, and became the hero's trademark symbol, akin to the red and yellow "S" symbol of Superman.[99] The overall look of the character, particularly the length of the cowl's ears and of the cape, varies greatly depending on the artist. Dennis O'Neil said, "We now say that Batman has two hundred suits hanging in the Batcave so they don't have to look the same . . . Everybody loves to draw Batman, and everybody wants to put their own spin on it."[100]

Equipment

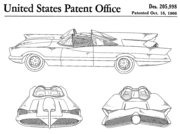

Batman utilizes a large arsenal of specialized gadgets in his war against crime, the designs of which usually share a bat motif. Batman historian Les Daniels credits Gardner Fox with creating the concept of Batman's arsenal with the introduction of the utility belt in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939) and the first bat-themed weapons the batarang and the "Batgyro" in Detective Comics #31 and #32 (September; October, 1939).[16] Batman's primary vehicle is the Batmobile, which is usually depicted as an imposing black car with large tailfins that suggest a bat's wings. Batman's other vehicles include the Batplane (aka the Batwing), Batboat, Bat-Sub, and Batcycle.

In proper practice, the "bat" prefix (as in batmobile or batarang) is rarely used by Batman himself when referring to his equipment, particularly after some portrayals (primarily the 1960s Batman live-action television show and the Super Friends animated series) stretched the practice to campy proportions. The 1960s television series Batman has an arsenal that includes such "bat-" names as the bat-computer, bat-scanner, bat-radar, bat-cuffs, bat-pontoons, bat-drinking water dispenser, bat-camera with polarized bat-filter, bat-shark repellent bat-spray, and bat-rope. The storyline "A Death in the Family" suggests that given Batman's grim nature, he is unlikely to have adopted the "bat" prefix on his own.

Batman keeps most of his field equipment in a utility belt. Over the years it is shown to contain a virtually limitless variety of crime fighting tools. Different versions of the belt have these items stored in either pouches or hard cylinders attached evenly around it.

Bat-Signal

When Batman is needed, the Gotham City police activate a searchlight with a bat-shaped insignia over the lens called the Bat-signal which shines into the night sky, creating a bat-symbol on a passing cloud which can be seen from any point in Gotham. The origin of the signal varies, depending on the continuity and medium.

In various incarnations, most notably the 1960s Batman TV series, Commissioner Gordon also has a dedicated phone line, dubbed the Bat-Phone, connected to a bright red telephone (in the TV series) which sits on a wooden base and has a transparent cake cover on top. The line connects directly to Batman's residence, Wayne Manor, specifically both to a similar phone sitting on the desk in Bruce Wayne's study and the extension phone in the Batcave.

Batcave

The Batcave is Batman's secret headquarters, consisting of a series of subterranean caves beneath his Wayne Manor. It serves as his command center for both local and global surveillance, as well as housing his vehicles and equipment for his war on crime. It also is a storeroom for Batman's memorabilia. In both the comic Batman: Shadow of the Bat (issue #45) and the 2005 film Batman Begins, the cave is said to have been part of the Underground Railroad. Of the heroes and villains who see the Batcave, few know where it is located.

Supporting characters

Batman's interactions with the characters around him, both heroes and villains, help to define the character.[52] Commissioner James "Jim" Gordon, Batman's ally in the Gotham City police, debuted along with Batman in Detective Comics #27 and has been a consistent presence since then. Later on, Batman gained Alfred as his butler and Lucius Fox as his business manager and apparently unwitting armorer. However, the most important supporting role in the Batman mythos is filled by the hero's young sidekick Robin.[101] The first Robin, Dick Grayson, eventually leaves his mentor and becomes the hero Nightwing. The second Robin, Jason Todd, is beaten to death by the Joker but later returns as an adversary. Tim Drake, the third Robin, first appears in 1989 and has gone on to star in his own comic series. Alfred, Bruce Wayne's loyal butler, father figure, and one of the few to know his secret identity, "[lends] a homey touch to Batman's environs and [is] ever ready to provide a steadying and reassuring hand" to the hero and his sidekick.[102]

Batman is at times a member of superhero teams such as the Justice League of America and the Outsiders. Batman has often been paired in adventure with his Justice League teammate Superman, notably as the co-stars of World's Finest and Superman/Batman series. In pre-Crisis continuity, the two are depicted as close friends; however, in current continuity, they have a mutually respectful but uneasy relationship, with an emphasis on their differing views on crime fighting and justice.

Batman is involved romantically with many women throughout his various incarnations. These range from society women such as Vicki Vale and Silver St. Cloud, to allies like Wonder Woman and Sasha Bordeaux, to even villainesses such as Catwoman and Talia al Ghul, the latter of whom he sired a son, Damien. While these relationships tend to be short, Batman's attraction to Catwoman is present in nearly every version and medium in which the characters appear. Authors have gone back and forth over the years as to how Batman manages the 'playboy' aspect of Bruce Wayne's personality; at different times he embraces or flees from the women interested in attracting "Gotham's most eligible bachelor".

Other supporting characters in Batman's world include former Batgirl Barbara Gordon, Commissioner Gordon's daughter who, now confined to a wheelchair due to a gunshot wound inflicted by the Joker, serves the superhero community at large as the computer hacker Oracle; Azrael, a would-be assassin who replaces Bruce Wayne as Batman for a time; Cassandra Cain, an assassin's daughter who became the new Batgirl, Huntress, the sole surviving member of a mob family turned Gotham vigilante who has worked with Batman on occasion, Stephanie Brown, the daughter of a criminal who operated as the Spoiler and temporarily as Robin, Ace the Bat-Hound, Batman's pet dog;[103] and Bat-Mite, an extra-dimensional imp who idolizes Batman.[103]

Enemies

Batman faces a variety of foes ranging from common criminals to outlandish super-villains. Many Batman villains mirror aspects of the hero's character and development, often having tragic origin stories that lead them to a life of crime.[102] Batman's "most implacable foe" is the Joker, a clown-like criminal who as a "personification of the irrational" represents "everything Batman [opposes]."[24] Other recurring antagonists include Catwoman, the Penguin, the Riddler and Two-Face, among many others.

Cultural impact

Batman has become a pop culture icon, recognized around the world. The character's presence has extended beyond his comic book origins; events such as the release of the 1989 Batman film and its accompanying merchandising "brought the Batman to the forefront of public consciousness."[48] In an article commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the character, The Guardian wrote, "Batman is a figure blurred by the endless reinvention that is modern mass culture. He is at once an icon and a commodity: the perfect cultural artefact for the 21st century."[104] In addition, media outlets have often used the character in trivial and comprehensive surveys- Forbes Magazine estimated Bruce Wayne to be the 7th-richest fictional character with his $6.8 billion fortune[105] while BusinessWeek listed the character as one of the ten most intelligent superheroes appearing in American comics.[106]

Adaptations in other media

The character of Batman has appeared in various media aside from comic books. The character has been developed as a vehicle for newspaper syndicated comic strips, books, radio dramas, television and several theatrical feature films. The first adaptation of Batman was as a daily newspaper comic strip which premiered on October 25, 1943.[107] That same year the character was adapted in the 13-part serial Batman, with Lewis Wilson becoming the first actor to portray Batman on screen. While Batman never had a radio series of his own, the character made occasional guest appearance in The Adventures of Superman starting in 1945 on occasions when Superman voice actor Bud Collyer needed time off.[108] A second movie serial, Batman and Robin, followed in 1949, with Robert Lowery taking over the role of Batman. The exposure provided by these adaptations during the 1940s "helped make [Batman] a household name for millions who never bought a comic book."[108].

In the 1964 publication of Donald Barthelme's collection of short stories "Come Back, Dr. Caligari" Barthelme wrote "The Joker's Greatest Triumph". Batman is portrayed as a pertentious french speaking rich man and subtle alcoholic.

The Batman television series, starring Adam West, premiered in January 1966 on the ABC television network. Inflected with a camp sense of humor, the show became a pop culture phenomenon. In his memoir, Back to the Batcave, West notes his dislike for the term 'camp' as it was applied to the 1960s series, opining that the show was instead a farce or lampoon, and a deliberate one, at that. The series ran for 120 episodes, ending in 1968. In between the first and second season of the Batman television series the cast and crew made the theatrical release Batman (1966). The popularity of the Batman TV series also resulted in the first animated adaptation of Batman in the series The Batman/Superman Hour;[109] the Batman segments of the series were repackaged as Batman with Robin the Boy Wonder which produced thirty-three episodes between 1968 and 1977. From 1973 until 1984, Batman had a starring role in ABC's Super Friends series, which was animated by Hanna-Barbera. Olan Soule was the voice of Batman in all these series, but was eventually replaced during Super Friends by Adam West, who voiced the character in Filmation's 1977 series The New Adventures of Batman.

Batman returned to movie theaters in 1989, with director Tim Burton's Batman starring Michael Keaton. Burton's film was a huge success; not only was it the top-grossing film of the year, but at the time was the fifth highest-grossing film in history.[110] The film spawned three sequels: Batman Returns (1992), Batman Forever (1995) and Batman & Robin (1997), the last two of which were directed by Joel Schumacher instead of Burton, and replaced Keaton with Val Kilmer and George Clooney, respectively.

In 1992 Batman returned to television in Batman: The Animated Series, which was produced by Warner Bros. and was broadcast on the Fox television network until 1997. After that point it moved to The WB Television Network and was reworked into The New Batman Adventures. The producers of Batman: The Animated Series would go to work on the animated feature film release Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (1993), as well as the futuristic Batman Beyond and Justice League series. Like Batman: The Animated Series, these productions starred Kevin Conroy as the voice of Batman/Bruce Wayne. In 2004, a new animated series titled The Batman made its debut with Rino Romano as the title character. In 2008, this series was replaced by another animated show, Batman: The Brave and the Bold, with Diedrich Bader as Batman.

In 2005 Christopher Nolan directed Batman Begins, a reboot of the film franchise starring Christian Bale as Batman. Its sequel, The Dark Knight (2008), set the record for the highest grossing opening weekend of all time in the U.S., earning approximately $158 million,[112] and became the fastest film to reach the $400 million mark in the history of American cinema (eighteenth day of release).[113] As of November 2008[update], The Dark Knight has the second-highest domestic gross of all films.[114] An animated anthology feature set between the Nolan films, Batman: Gotham Knight, was also released in 2008. The Dark Knight also pays homage to the comic Batman by making the character's eyes white during a minor scene in the movie.

Batman has several video games based on him and his crime fighting adventures.

Homosexual interpretations

There has been some controversy over various sexual interpretations made regarding the content of Batman comics. Homosexual interpretations have been part of the academic study of Batman since psychologist Fredric Wertham asserted in 1954 Seduction of the Innocent that "Batman stories are psychologically homosexual". He claimed, "The Batman type of story may stimulate children to homosexual fantasies, of the nature of which they may be unconscious". Wertham wrote, "Only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and of the psychopathology of sex can fail to realize a subtle atmosphere of homoeroticism which pervades the adventures of the mature 'Batman' and his young friend 'Robin'".[115]

Andy Medhurst wrote in his 1991 essay "Batman, Deviance, and Camp" that Batman is interesting to gay audiences because "he was one of the first fictional characters to be attacked on the grounds of his presumed homosexuality," "the 1960s TV series remains a touchstone of camp," and "[he] merits analysis as a notably successful construction of masculinity."[116]

Creators associated with the character have expressed their own opinions. Writer Alan Grant has stated, "The Batman I wrote for 13 years isn't gay. Denny O'Neil's Batman, Marv Wolfman's Batman, everybody's Batman all the way back to Bob Kane... none of them wrote him as a gay character. Only Joel Schumacher might have had an opposing view". Writer Devin Grayson has commented, "It depends who you ask, doesn't it? Since you're asking me, I'll say no, I don't think he is ... I certainly understand the gay readings, though".[117] While Frank Miller has described the relationship between Batman and the Joker as a "homophobic nightmare",[118] he views the character as sublimating his sexual urges into crime fighting, concluding, "He'd be much healthier if he were gay".[119] Burt Ward, who portrayed Robin in the 1960s television show, has also remarked upon this interpretation in his autobiography Boy Wonder: My Life in Tights; He writes that the relationship could be interpreted as a sexual one, with the show's double entendres and lavish camp also possibly offering ambiguous interpretation.[120]

Such homosexual interpretations continue to attract attention. One notable example occurred in 2000, when DC Comics refused to allow permission for the reprinting of four panels (from Batman #79, 92, 105 and 139) to illustrate Christopher York's paper All in the Family: Homophobia and Batman Comics in the 1950s.[121] Another happened in the summer of 2005, when painter Mark Chamberlain displayed a number of watercolors depicting both Batman and Robin in suggestive and sexually explicit poses.[122] DC threatened both artist and the Kathleen Cullen Fine Arts gallery with legal action if they did not cease selling the works and demanded all remaining art, as well as any profits derived from them.[123]

Notes

- ^ a b c Beatty, Scott (2008), "Batman", in Dougall, Alastair, The DC Comics Encyclopedia, London: Dorling Kindersley, pp. 40–44, ISBN 0-7566-4119-5

- ^ "The Big Question: What is the history of Batman, and why does he still appeal?". The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/film-and-tv/features/the-big-question-what-is-the-history-of-batman-and-why-does-he-still-appeal-873780.html.

- ^ Daniels, Les. Batman: The Complete History. Chronicle Books, 1999. ISBN 0-8118-4232-0, pg. 18

- ^ Steranko, Jim. The Steranko History of Comics 1. Reading, PA: Supergraphics, 1970. (ISBN 0-517-50188-0)

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 21, 23

- ^ Havholm, Peter; Sandifer, Philip (Autumn 2003). "Corporate Authorship: A Response to Jerome Christensen". Critical Inquiry 30 (1): 192. doi:. ISSN 00931896.

- ^ a b Kane, Andrae, p. 44

- ^ Daniels, Les. DC Comics: A Celebration of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes. New York: Billboard Books/Watson-Guptill Publications, 2003, ISBN 0-8230-7919-8, pg. 23

- ^ Boichel, Bill. "Batman: Commodity as Myth." The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Routledge: London, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-276-7, pg. 6–7

- ^ Kane, Andrae, p. 41

- ^ Groth, Gary (October 2005). "Jerry Robinson". The Comics Journal 1 (271): 80–81. ISSN 0194-7869. http://www.tcj.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=350&Itemid=48. Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ^ Comic Book Artist 3. Winter 1999. TwoMorrows Publishing

- ^ "Comic Book Interview Super Special: Batman" Fictioneer Press, 1989

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 25

- ^ Wright, Bradford W. Comic Book Nation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2001. ISBN 0-8018-7450-5, pg. 19

- ^ a b Daniels (1999), pg. 29

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Bob Kane (p), Sheldon Moldoff (i). "The Batman and How He Came to Be". Detective Comics (November, 1939). DC Comics. (1-2).

- ^ Detective Comics #33 (Nov. 1939), Grand Comics Database

- ^ John Jefferson Darowski, "The Mythic Symbols of Batman" December 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-20. Archived on 2008-03-20.

- ^ a b Wright, pg. 17

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 38

- ^ Daniels (2003), pg. 36

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 42

- ^ a b Boichel, pg. 9

- ^ Wright, pg. 59

- ^ Edmund Hamilton (w), Curt Swan (p). "The Mightiest Team In the World". Superman #76 (June 1952). DC Comics.

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 88

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 91

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 84

- ^ Boichel, pg. 13

- ^ York, Christopher (2000). "All in the Family: Homophobia and Batman Comics in the 1950s". The International Journal of Comic Art 2 (2): 100–110.

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 94

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 95

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Sheldon Moldoff (p). "Gotham Gang Line-Up!". Detective Comics (June, 1964). DC Comics.

- ^ Detective Comics #31 and Batman #227, Grand Comics Database

- ^ Benton, Mike. The Comic Book in America: An Illustrated History. Dallas: Taylor, 1989. ISBN 0-87833-659-1, pg. 69

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 115

- ^ Wright, pg. 233

- ^ Pearson, Roberta E.; Uricchio, William. "Notes from the Batcave: An Interview with Dennis O'Neil." The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Routledge: London, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-276-7, pg. 18

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 140

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 141

- ^ SciFi Wire (March 28, 2007): "Batman Artist Rogers is Dead": "Even though their Batman run was only six issues, the three laid the foundation for later Batman comics. Their stories include the classic 'Laughing Fish' (in which the Joker's face appeared on fish); they were adapted for Batman: The Animated Series in the 1990s. Earlier drafts of the 1989 Batman movie with Michael Keaton as the Dark Knight were based heavily on their work".

- ^ Boichel, pg. 15

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 147, 149

- ^ Wright, pg. 267

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 155, 157

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 161

- ^ a b Pearson, Roberta E.; Uricchio, William. "Introduction." The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Routledge: London, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-276-7, pg. 1

- ^ "Diamond's 2005 Year-End Sales Charts & Market Share" (http). newsarama.com. 2006. http://www.newsarama.com/marketreport/05Year_End.html. Retrieved on October 26 2006.[dead link]

- ^ "July 2005 Sales Charts: All-Star Batman & Robin Lives Up To Its Name" (http). newsarama.com. 2005. http://www.newsarama.com/marketreport/july05sales.html. Retrieved on October 26 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Pearson, pg. 185

- ^ a b c d e f Pearson; Uricchio. "'I'm Not Fooled By That Cheap Disguise.'" Pg. 186

- ^ Pearson, pg. 191

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Bob Kane (p). "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate". Detective Comics #27 (May, 1939). DC Comics.

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Bob Kane (p). "The Batman Wars Against the Dirigible of Doom". Detective Comics #33 (November, 1939). DC Comics.

- ^ She first appears in Detective Comics #31 (Sept. 1939)

- ^ Paul Levitz (w), Joe Staton (p). "The Untold Origin of the Justice Society". DC Special (August/September 1977). DC Comics.

- ^ Gardner Fox (w). All Star Comics. (Winter 1940/41). DC Comics.

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Bob Kane (p). Batman. (November, 1941). DC Comics.

- ^ Batman #16 (May 1943); his original last name, Beagle, is revealed in Detective Comics #96 (Feb. 1945)

- ^ One example is the Englehart/Rogers run of the late 1970s, which has editorial notes directing readers to issues such as Batman #1

- ^ Bill Finger (w), Sheldon Moldoff (p). "The First Batman". Detective Comics (September, 1956). DC Comics.

- ^ Edmond Hamilton (w), Dick Sprang (p). "When Batman Was Robin". Detective Comics (December, 1955). DC Comics.

- ^ Miller, Frank; David Mazzucchelli and Richmond Lewis (1987). Batman: Year One. DC Comics. p. 98. ISBN 1-85286-077-4.

- ^ Max Allan Collins (w), Chris Warner (p). "Did Robin Die Tonight?". Batman (June, 1987). DC Comics.

- ^ Alan Grant (w), Norm Breyfogle (p). "Master of Fear". Batman (December, 1990). DC Comics.

- ^ Dixon, Chuck. et al. "Batman: Prodigal". Batman 512-514, Shadow of the Bat 32-34, Detective Comics 679-681, Robin 11-13. New York: DC Comics, 1995.

- ^ 52 #30

- ^ Batman #673

- ^ Batman #681

- ^ James Robinson (w), Don Kramer (p). "Face the Face – Conclusion". Batman (August, 2006). DC Comics.

- ^ Brad Meltzer (w), Ed Benes (p). "The Tornado's Path". Justice League of America (vol. 2) (August, 2006). DC Comics.

- ^ Chuck Dixon (w), Julian Lopex (p). Batman and the Outsiders (vol. 2). (November, 2007). DC Comics.

- ^ Rothstein, Simon. "Batman killed by his OWN dad". 28 November 2008. The Sun. Archived 28 November 2008.

- ^ Adams, Guy. "Holy smoke, Batman! Are you dead?" 28 November 2008, The Independent. Archived 28 November 2008.

- ^ Newsarama: "Batman R.I.P. - Finally?" 15 January 2009

- ^ Grant Morrison (w), J.G. Jones (p). "How to Murder the Earth". Final Crisis #6 (January 2009). DC Comics.

- ^ Grant Morrison (w). Final Crisis #7. (January 2009). DC Comics.

- ^ Pearson; Uricchio. "Notes from the Batcave: An Interview with Dennis O'Neil" p. 23

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 31

- ^ Pearson, pg. 194

- ^ Sharrett, Christopher. "Batman and the Twilight of the Idols: An Interview with Frank Miller." The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Routledge: London, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-276-7, pg. 44

- ^ Pearson, pg. 208

- ^ Dennis O'Neil Batman: Knightfall. 1994, Bantam Books. ISBN 0553096737

- ^ Pearson, pg. 202

- ^ Daniels, 1999, pg. ??

- ^ Scott Beatty, The Batman Handbook: The Ultimate Training Manual. 2005, Quirk Books, p51. ISBN 1594740232

- ^ Aichele, G. (1997). Rewriting Superman. In G. Aichele & T. Pippin (Eds.), The Monstrous and the Unspeakable: The Bible as Fantastic Literature (pp. 75-101). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- ^ Superman vol. 2, #53

- ^ Mike Conray, 500 Great Comicbook Action Heroes. 2002, Collins & Brown. ISBN 1844110044

- ^ Grant Morrison (w), Howard Porter (p). "War of the Worlds". JLA (March, 1997). DC Comics.

- ^ Koç, E. "Rebirth of the Gothic in the Metropolitan Legends" Çankaya Üniversitesi, Journal of Arts and Sciences (2006 Aralık)

- ^ a b c d Daniels (1999)

- ^ Widzer, M.E. (1977). The Comic-Book Superhero—A Study of the Family Romance Fantasy. Psychoanal. St. Child, 32:565-603.

- ^ Bill Schelly, Sense of Wonder: A Life in Comic Fandom : a Personal Memoir of Fandom's. 2001 TwoMorrows Publishing, p24. ISBN 1893905128

- ^ Illinca Zarifopol-Johnston, "A BatsEye View of the Republic or Victor Hugo" in Peripheries of Nineteenth-century French Studies: Views from the Edge, Timothy Bell Raser ed. 2002, University of Delaware Press, p184. ISBN 0874137659

- ^ Jim Harmon, Donald F. Glut, Great Movie Serials: Their Sound and Fury. 1973 Routledge, p234. ISBN 071300097X

- ^ Larry Ford, "Lighting and Color in the Depiction" in Place, Power, Situation, and Spectacle: A Geography of Film, Stuart C. Aitken, Leo Zonn, Leo E. Zonn eds. 1994 Rowman & Littlefield, p132. ISBN 0847678261

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 98

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 159–60

- ^ Boichel, pg. 7

- ^ a b Boichel, pg. 8

- ^ a b Daniels (1995), pg. 138

- ^ Finkelstein, David; Macfarlane, Ross (March 15, 1999). "Batman's big birthday". Guardian.co.uk. http://www.guardian.co.uk/g2/story/0,,314504,00.html. Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ^ Noer, Michael; David M.Ewalt (2006-11-20). "The Forbes Fictional 15". Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2006/11/16/forbes-fictional-rich-tech-media-cx_mn_de_06fict15_land.html. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

- ^ Pisani, Joseph (2006). "The Smartest Superheroes". www.businessweek.com. http://images.businessweek.com/ss/06/05/smart_heroes/index_01.htm. Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 50

- ^ a b Daniels (1999), pg. 64

- ^ Boichel, pg. 14

- ^ "Batman (1989)". BoxOfficeMojo.com. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=batman.htm. Retrieved on 2007-05-27.

- ^ Daniels (1999), pg. 178

- ^ "Opening Weekends". BoxOfficeMojo.com. http://boxofficemojo.com/alltime/weekends/. Retrieved on 2008-07-20.

- ^ "Fastest to $400 million". BoxOfficeMojo.com. http://boxofficemojo.com/alltime/fastest.htm?page=400&p=.htm. Retrieved on 2008-08-06.

- ^ "All Time Domestic Box Office Results". BoxOfficeMojo.com. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/alltime/domestic.htm. Retrieved on 2008-11-23.

- ^ Wertham, Fredric. Seduction of the Innocent. Rinehart and Company, Inc., 1954. pg. 189–90

- ^ Medhurst, Andy. "Batman, Deviance, and Camp." The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Routledge: London, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-276-7, pg. 150

- ^ "Is Batman Gay?". http://www.comicsbulletin.com/panel/106070953757230.htm. Retrieved on December 28 2005.

- ^ Sharrett, pg. 37-38

- ^ Sharrett, pg. 38

- ^ "Bruce Wayne: Bachelor". Ninth Art: Andrew Wheeler Comment. http://www.ninthart.com/display.php?article=963. Retrieved on June 21 2005.

- ^ Beatty, Bart (2000). "Don't Ask, Don't Tell: How Do You Illustrate an Academic Essay about Batman and Homosexuality?". The Comics Journal (228): 17–18.

- ^ "Mark Chamberlain (American, 1967)". Artnet. http://www.artnet.com/Galleries/Artists_detail.asp?G=&gid=423822183&which=&aid=424157172&ViewArtistBy=online&rta=http://www.artnet.com/ag/fulltextsearch.asp?searchstring=Mark+Chamberlain.

- ^ "Gallery told to drop 'gay' Batman". BBC. August 19, 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4167032.stm.

References

- Beatty, Scott, et al., The Batman Handbook: The Ultimate Training Manual. Quirk Books, 2005. ISBN 1-59474-023-2

- Daniels, Les. Batman: The Complete History. Chronicle Books, 1999. ISBN 0-8118-4232-0

- Daniels, Les. DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes. Bulfinch, 1995. ISBN 0-821-22076-4

- Jones, Gerard. Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book. Basic Books, 1995. ISBN 0-465-03657-0

- Pearson, Roberta E.; Uricchio, William (editors). The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media. Routledge: London, 1991. ISBN 0-85170-276-7

- Wright, Bradford W. Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. Johns Hopkins, 2001. ISBN 0-8018-7450-5

External links

![]() Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks

![]() Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote

![]() Source texts from Wikisource

Source texts from Wikisource

![]() Images and media from Commons

Images and media from Commons

![]() News stories from Wikinews

News stories from Wikinews