Mirtazapine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

|

Mirtazapine

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

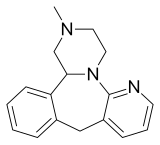

| 2-methyl-1,2,3,4,5a,9a,10,14b-octahydrobenzo[c]pyrazino[1,2-a]pyrido[3,2-f]azepine | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | N06 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C17H19N3 |

| Mol. mass | 265.36 |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Half life | 37 hours (females), 26 hours (males) |

| Excretion | 75% urine 15% feces |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. |

C |

| Legal status |

Prescription only |

| Routes | Oral tablet, Soluble tablet |

Mirtazapine is an antidepressant introduced by Organon International in 1994 used for the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Mirtazapine has a tetracyclic chemical structure and is classified as a Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressant (NaSSA). Mirtazapine and maprotiline are the only tetracyclic antidepressants that have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat depression. Because of its unique structure, mirtazapine has fewer anticholinergic effects, serotonin-related side effects and adrenergic side effects (such as orthostatic hypotension and sexual dysfunction) compared to other antidepressants. Antihistaminic side effects of drowsiness and weight gain are prominent. It is most useful as an add-on medication to enhance the effectiveness of agents such as duloxetine, bupropion and venlafaxine in severe and treatment-resistant depression. Mirtazapine is relatively safe if an overdose is taken.

Contents |

[edit] Trade names

Mirtazapine is marketed under the tradenames:

- Avanza, Axit and Mirtazon in Australia

- Míron in Iceland

- Mirtabene in Austria

- Mirtaz in India and Srilanka

- Mirtazapin in Finland and Denmark

- Mirzagen in Saudi Arabia

- Mirzaten , Mizapin Sol and Remeron in Hungary, Poland and Slovakia

- Norset in France

- Noxibel in Bolivia

- Promyrtil in Chile

- Psidep in Portugal

- Remergil in Germany

- Remergon in Belgium

- Esprital in Czech Republic

- Remeron in Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Israel, Italy, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Romania, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States.

- Rexer in Spain

- Zispin in Ireland and the United Kingdom

[edit] Indications

[edit] Approved use

Mirtazapine is primarily used to treat the symptoms of moderate to severe depression.

[edit] Unapproved and off-label use

There is evidence that mirtazapine can be used to treat insomnia, panic disorder (PD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) sleep apnea, and pruritus. It can also be used to offset the gastro-intestinal side effects of SSRIs .

Mirtazapine has been reported to be effective in the prophylactic treatment of chronic tension headache. Due to the common side effect of weight gain, it may also be beneficial to patients who are underweight or have reduced appetite.

There is some evidence that mirtazapine may have a beneficial effect in Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) by reducing JC virus proliferation. It is being used now (2008) cautiously in immunosuppressed PML patients to evaluate its efficacy.

Due to its anti-emetic properties via 5HT-3 receptor antagonism, mirtazapine is helpful in the treatment of many nausea and emesis-enducing conditions. Mirtazapine has proven helpful in treating the digestive disorder gastroparesis, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, vomiting following gastric bypass surgery, and hyperemesis gravidarum.

[edit] Veterinary use

Mirtazapine is used off-label as an appetite stimulant in dogs and cats. Cats are often only given this medication once every three days, which can be convenient for owners.

Anecdotal evidence also suggests that mirtazapine may be effective in treating certain vomiting or anorexia-related conditions in dogs and cats. Any such use is still off-label, however.

[edit] Mechanism of action

It is thought to work by blocking presynaptic Alpha-2 adrenergic receptors that normally inhibit the release of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and serotonin, thereby increasing active levels in the synapse. Mirtazapine is a potent antagonist of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors. Mirtazapine has no significant affinity for the 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors.

[edit] Side effects

Interestingly, its side-effect profile can be used for benefit in certain clinical situations. The drowsiness, increased appetite, and weight gain that it causes are useful in patients with depressive disorders with prominent sleep and appetite disturbances.

In addition, it can be used in patients who suffer from nausea, since it is a 5HT-3 antagonist, the target of the popular anti-emetic ondansetron (Zofran).

At lower doses, mirtazapine is primarily antihistaminergic, causing sedation, which can be beneficial in depressed patients who have difficulty falling asleep. Higher doses are generally less sedating as its antihistaminergic properties are thought to be offset by increased noradrenaline release.

[edit] Side effects occurring commonly

- Drowsiness, especially at lower doses and during the first few weeks of treatment

- Vivid dreams / Nightmares as a result of regular intake

- Increased appetite

- Weight gain

- Increase in cholesterol, independent of weight gain

- Dizziness, coupled often with the effects of sickness

- Headache

- Dry mouth

[edit] Side effects occurring rarely

- Excessive urinating when taken with alcohol

- Mania

- Seizures

- Tremor

- Muscle twitching and Restless Legs Syndrome[1][2]

- Pins and needles

- Rash and skin eruptions

- Pain in the joints or muscles

- Low blood pressure

- Higher blood pressure

- Obesity

- Mild visual hallucinations (when taken during the day or when awake)

- Depersonalization / Derealization (i.e. feeling unreal, in a dream-like state)

- Oedema (swollen ankles or feet)

[edit] Dangerous side effects

Any of these side effects requires urgent medical attention. Medical advice is also required for taper-off instructions: sudden withdrawal from antidepressants can cause serious symptoms. However, sudden withdrawal can be used, under appropriate medical supervision, when the risks of continuing the antidepressant during a 'taper-off' phase are too great.

- An allergic reaction; signs of swelling of the lips, face and tongue, difficulty in breathing, rash or itching (especially affecting the whole body) or feeling faint

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and/or eyes)

- Agranulocytosis, a lowering of white blood cells used to fight infection in the body. Signs of infection such as fever, sore throat, mouth ulcers or stomach upset should be monitored closely. Occurs in 1/1000 patients.

[edit] Withdrawal symptoms

Antidepressants in general have some dependence producing effects, most notably a withdrawal syndrome. However, their dependence producing properties are not as significant as benzodiazepines. For example antidepressants have little to no abuse potential unlike benzodiazepines.[3] An abrupt or overrapid reduction of antidepressants including mirtazapine can cause a discontinuation or withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal symptoms may also occur in the neonate.[4] As with most antidepressants, a gradual and slow reduction in dose is recommended in order to minimize the discontinuation syndrome withdrawal effects.[5] Effects of sudden cessation of treatment may include:[6][7]

- Anxiety and panic attacks[8]

- Flu like symptoms

- Gastrointestinal disturbances

- Headache

- Mania or hypomania[9][10]

- Insomnia

- Irritability

- Nausea and vomiting

- Restlessness

- Sensory disturbances

[edit] Dosage

The usual starting dose for mirtazapine is 15mg once daily, usually at bedtime (because of its sedative nature and the possibility of disturbed visual perception). Doses may be increased, following medical advice, every 1-2 weeks up to a dose of 45mg.

In psychiatric inpatients doses 60, 90 and sometimes even 120 mg are used successfully for treating treatment-resistant depression.

It may be taken with or without food. Dispersible tablets (SolTab orally disintegrating tablets) can be taken without water.

[edit] Pregnancy and lactation

- Pregnancy : Sufficient data in humans is lacking. The use should be justified by the severity of the condition to be treated.

- Lactation : Sufficient data in humans is also lacking. Additionally, Mirtazapine may be found in the maternal milk in significant concentrations. The use in breastfeeding women should be carefully weighed against possible risks.

[edit] Interactions with other drugs

Because of the sedative effects of Mirtazapine, excessive sedation may result when it is used with other sedating substances, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines.

According to official prescribing information from Organon, Mirtazapine should not be used within 14 days of the use of an MAOI because of the risk of serious effects such as hypertensive emergency and hyperthermia.

[edit] References

- ^ Gillman, PK (2006). "A systematic review of the serotonergic effects of mirtazapine: implications for its dual action status". Human Psychopharmacology Clinical and Experimental 21 (2): 117–25. doi:. PMID 16342227.

- ^ Burrows GD, Kremer CM. (1997). "Mirtazapine: clinical advantages in the treatment of depression". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 17 (2S): 34S–39S. doi:. PMID 9090576.

- ^ Velazquez C, Carlson A, Stokes KA, Leikin JB. (2001). "Relative safety of mirtazapine overdose". Veterinary and Human Toxicology 43 (6): 342–344. PMID 11757992.

- ^ Gorman JM (1999). "Mirtazapine: clinical overview". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60 (17): 9–13. PMID 10446735.

- ^ Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, Bandelow B, Bond A, Davidson JR, den Boer JA, Fineberg NA, Knapp M, Scott J, Wittchen HU (2005). "Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology 19 (6): 567–596. doi:. PMID 16272179.

- ^ Goodnick PJ, Puig A, DeVane CL, Freund BV (1999). "Mirtazapine in major depression with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60 (7): 446–448. PMID 10453798.

- ^ Koran LM, Gamel NN, Choung HW, Smith EH, Aboujaoude EN (2005). "Mirtazapine for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial followed by double-blind discontinuation". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66 (4): 515–520. PMID 15816795.

- ^ "First Effective Drug For Sleep Disorder Identified". Science Daily. 2003-06-05. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2003/06/030605081837.htm. Retrieved on 2008-05-01.

- ^ Davis MP, Frandsen JL, Walsh D, Andresen S, Taylor S. (2003). "Mirtazapine for pruritus". Journal of pain and symptom management 25 (3): 288–291. doi:. PMID 12614964.

- ^ Caldis E V (2004). "Mirtazapine for treatment of nausea induced by selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.". Can J Psychiatry 49: 707. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15560319.

- ^ Bendtsen L, Jensen R (2004). "Mirtazapine is effective in the prophylactic treatment of chronic tension-type headache". Neurology 62 (10): 1706–1711. PMID 15159466.

- ^ Kim S (2006). "Mirtazapine for Severe Gastroparesis Unresponsive to Conventional Prokinetic Treatment". Psychosomatics 47: 440-442. http://psy.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/47/5/440.

- ^ Kast R E (2007). "Cancer chemotherapy and cachexia: mirtazapine and olanzapine are 5-HT3 antagonists with good antinausea effects". European Journal of Cancer Care 16: 351-354. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/117989553/PDFSTART.

- ^ Thompson D S (2000). "Mirtazapine for the Treatment of Depression and Nausea in Breast and Gynecological Oncology". Psychosomatics 41: 356-359. http://psy.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/41/4/356.

- ^ Teixeira F V (2005). "Mirtazapine (Remeron™) as Treatment for Non-Mechanical Vomiting after Gastric Bypass". Obesity Surgery 15: 707-709. http://www.springerlink.com/content/h21q680685401j1v/.

- ^ Rohde A (2003). "Mirtazapine (Remergil) for treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum: rescue of a twin". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 268: 219-221. http://www.springerlink.com/content/6dn93jy421xqdr14/.

- ^ Brooks DVM, DipABVP, Wendy C. (2007-04-30). "Mirtazapine (Remeron)". The Pet Pharmacy. http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&A=2552. Retrieved on 2008-03-06.

- ^ Nash J, Nutt D (2004). "Antidepressants". Psychiatry 6 (7): 289–294.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Bonin B, Vandel P, Kantelip JP (2000). "Mirtazapine and restless leg syndrome: a case report". Therapie 55 (5): 655–6. PMID 11201984.

- ^ Rottach KG, Schaner BM, Kirch MH, et al (November 2008). "Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants". J Psychiatr Res 43 (1): 70–5. doi:. PMID 18468624.

- ^ van Broekhoven F, Kan CC, Zitman FG (June 2002). "Dependence potential of antidepressants compared to benzodiazepines". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 26 (5): 939–43. PMID 12369270. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0278-5846(02)00209-9.

- ^ Schwarzer, V; Heep, A; Gembruch, U; Rohde, A (January 2008). "Treatment resistant hyperemesis gravidarum in a patient with type 1 diabetes mellitus: neonatal withdrawal symptoms after successful antiemetic therapy with mirtazapine". Archives of gynecology and obstetrics 277 (1): 67–9. doi:. PMID 17628816.

- ^ Vlaminck, Jj; Van, Vliet, Im; Zitman, Fg (March 2005). "Withdrawal symptoms of antidepressants" (Free full text). Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde 149 (13): 698–701. ISSN 0028-2162. PMID 15819135. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/antidepressants.html.

- ^ Benazzi, F (June 1998). "Mirtazapine withdrawal symptoms". Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 43 (5): 525. ISSN 0706-7437. PMID 9653542.

- ^ Berigan, Tr (June 2001). "Mirtazapine-Associated Withdrawal Symptoms: A Case Report" (PDF). Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry 3 (3): 143. ISSN 1523-5998. PMID 15014614. PMC: 181176. http://www.psychiatrist.com/pcc/pccpdf/v03n03/v03n0307.pdf.

- ^ Klesmer, J; Sarcevic, A; Fomari, V (August 2000). "Panic attacks during discontinuation of mirtazepine". Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 45 (6): 570–1. ISSN 0706-7437. PMID 10986577.

- ^ Maccall, C; Callender, J (October 1999). "Mirtazapine withdrawal causing hypomania". The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science 175: 390. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 10789310.

- ^ Ali, S; Milev, R (May 2003). "Switch to mania upon discontinuation of antidepressants in patients with mood disorders: a review of the literature". Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 48 (4): 258–64. ISSN 0706-7437. PMID 12776393.

[edit] External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||