Tramadol

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

|

|

|

Tramadol

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (1R,2R)-2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | N02 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C16H25NO2 |

| Mol. mass | 263.4 g/mol |

| SMILES | & |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 68–72% Increases with repeated dosing. |

| Protein binding | 20% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic demethylation and glucuronidation |

| Half life | 5–7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | |

| Legal status | |

| Routes | oral, IV, IM, IV, rectal, sublingual, buccal |

Tramadol (INN) (pronounced /ˈtræmədɒl/) is a CNS depressant and analgesic, used for treating moderate to severe pain. It is a synthetic agent, and it appears to have actions at the μ-opioid receptor as well as the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems.[1][2][3] Tramadol was developed by the German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal GmbH in the late 1970s and marketed under the trade name Tramal.[4] Grünenthal has also cross licensed the drug to many other pharmaceutical companies that market it under various names such as MEDTRAP(NEOMED) Ultram and ULTRAM® ER. Tramadol's chemical structure is quite different from those of opiates. The closest chemical relative of tramadol in clinical use is tapentadol, which is a member of the same chemical class as tramadol and also developed by Grünethal.

Contents |

[edit] Uses

Tramadol is used to treat moderate to moderately severe pain and most types of neuralgia, including trigeminal neuralgia.[citation needed] It has been suggested that tramadol could be effective for alleviating symptoms of depression and anxiety because of its action on the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems, the involvement of which appear to play a part in its ability to alleviate the perception of pain. However, health professionals have not yet endorsed its use on a large scale for disorders such as this.[5][6]

[edit] Availability

Tramadol is usually marketed as the hydrochloride salt (tramadol hydrochloride); the tartrate is seen on rare occasions, and tramadol is available in both injectable (intravenous and/or intramuscular) and oral preparations. It is also available in conjunction with acetaminophen. The solutions suitable for injection are used in Patient Controlled Analgesia pumps under some circumstances, either as the sole agent or along with another agent such as morphine.

Specifically, tramadol comes in many forms, including:

- capsules

- tablets

- extended-release tablets

- extended-release capsules

- chewable tablets

- low-residue and/or uncoated tablets which can be taken by the sublingual and buccal routes

- suppositories

- effervescent tablets and powders

- ampoules of sterile solution for SC, IM, and IV injection

- preservative-free solutions for injection by the various spinal routes (epidural, intrathecal, caudal and others)

- powders for compounding

- liquids both with and without alcohol for oral and sublingual administration, available in regular phials and bottles, dropper bottles, bottles with a pump similar to those used with liquid soap and phials with droppers built into the cap

- tablets and capsules containing paracetamol (acetaminophen) and aspirin and other agents

Tramadol has been experimentally used in the form of an ingredient in multi-agent topical gels, creams, and solutions for nerve pain, rectal foam, concentrated retention enaema, and a skin plaster (transdermal patch) quite similar to those used with lidocaine.

Tramadol has a characteristic taste which is mildly bitter but much less so than morphine and codeine. Oral and sublingual drops and liquid preparations come with and without added flavouring. Its relative effectivness via transmucousal routes (sublingual, buccal, rectal) is around that of codeine and like codeine it is also metabolised in the liver to stronger metabolites (see below).

[edit] Dosage

Doses range from 50–400 mg daily, maximum dose of 400 mg a day according to the German package insert for both Grünethal's product Tramal 100 mg extended-release tablets and the Tramundal (Mundipharma Ges. m.b.H) 100 mg/ml dropper bottles and 100 and 200 ml dosage pump bottles), with up to 600 mg daily when given IV/IM. The formulation containing APAP contains 37.5 mg of tramadol and 325 mg of paracetamol, intended for oral administration with a common dosing recommendation of one or two tablets every four to six hours. Extended-release tablets lasting 8, 10, 12, 15, or 18 hours containing 100, 150, 200, and 250 mg of tramadol and 24-hour tablets containing up to 350 mg, and possibly 300 and/or 400 mg strengths are available in some countries.

Tramadol responds very well to opioid potentiators used to reduce the amount of medication needed to stop a given level of pain; the most effective appears to be promethazine, which also increases the percentage of the drug changed to stronger active metabolites in the liver as it does with the codeine-based opioid analgesics. Orphenadrine, hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, carisoprodol and benzodiazepines are commonly-used potentiators for tramadol and other drugs in its range of efficacy. Clonidine can reduce side effects and raise the de facto daily dosage ceiling for tramadol but may also competitively reduce the effects on nerve pain in some patients whilst having no effect or intensifying it in others.

Carbamazepine and some other agents can affect metabolism in such a way that tramadol single and 24-hour doses may have to be increased by as much as 120 per cent to have the same effect. In some patients, fluoxetine use within 15 days prior to starting tramadol can reduce the effectiveness of tramadol by the same Cytochrome p450-related mechanism that causes fluoxetine to wipe out the usefulness of codeine, dihydrocodeine, and similar drugs for a similar period. Combining fluoxetine and tramadol can increase the potential of some tramadol side effects and if done requires very close medical supervision and often can be made less problematic by the addition of a drug with antiserotonergic effects such as cyproheptadine, various phenothiazines, and anticonvulsants if the continuation of fluoxetine is important.

In addition to its use as the primary centrally-acting analgesic, tramadol can also be used with opioids in the place of adjuvants such as duloxetine to help combat neuropathic pain by broadening the spectrum of actions of the primary opioid (however, care should be exercised in giving duloxetine or SSRIs in combination with tramadol due to the possibility of serotonin syndrome); this is very useful with morphine, codeine, and its derivatives, somewhat useful with methadone, piritramide, and levorphanol (possibly because tramadol duplicates much more of the spectrum of effects of these drugs) and should be used only very cautiously with pethidine and most of its derivatives due to additive effects which can have toxic CNS and peripheral effects. Tramadol can generally be used alongside many other commonly used adjuvants like orphenadrine and related drugs, although those with impacts on serotonin and norepinephrine levels such as amitryptiline, cyclobenzaprine, duloxetine, and MAO inhibitors should be used alongside tramadol with caution and often with reduced doses of both agents.

Tramadol is used in topical creams, ointments, gels, liquids, and similar forms -- usually specially compounded -- for use against chronic nerve pain by means of application to the skin above the nerve involved as well as related trigger points and possibly other locations in the dermatome in question, often in conjunction with ketamine, ketoprofen and other NSAIDs, amide type and other local anaesthetics (most often lidocaine), and/or and other pain drugs of the adjuvant, atypical & potentiator type. The spectrum of tramadol's actions make it suitable for this purpose whereas most other opioids may not work in this fashion. In this respect tramadol's action is more like that of cyclobenzaprine and first-generation tricyclic anti-depressants like amitryptiline than it is like many other opioids.

[edit] Off-label and investigational uses

- diabetic neuropathy[7][8]

- postherpetic neuralgia[9][10]

- fibromyalgia[11]

- restless legs syndrome[12]

- opiate withdrawal management[13][14]

- migraine headache[15]

- obsessive-compulsive disorder[16]

- premature ejaculation[17]

[edit] Veterinary

Tramadol is used to treat post-operative, injury-related, and chronic (e.g. cancer-related) pain in dogs and cats [4] as well as rabbits, coatis, many small mammals including rats and flying squirrels, guinea pigs, ferrets and raccoons. Tramadol comes in ampoules in addition to the tablets, capsules, powder for reconstitution and oral syrups and liquids; the fact that its characteristic taste is not very bitter and can be masked in food and diluted in water makes for a number of means of administration. No data which would lead to a definitive determination of the efficacy and safety of tramadol in reptiles or amphibians is available at this time, and following the pattern of all other drugs it appears that tramadol can be used to relieve pain in marsupials such as North American opossums, Short-Tailed Opossums, sugar gliders, wallabies, and kangaroos amongst others.

[edit] Mechanism of action

The mode of action of tramadol has yet to be fully understood, but it is believed to work through modulation of the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems in addition to its mild agonism of the μ-opioid receptor. The contribution of non-opioid activity is demonstrated by the analgesic effects of tramadol not being fully antagonised by the μ-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone.

Tramadol is marketed as a racemic mixture with a weak affinity for the μ-opioid receptor (approximately 1/6000th that of morphine; Gutstein & Akil, 2006). The (+)-enantiomer is approximately four times more potent than the (-)-enantiomer in terms of μ-opioid receptor affinity and 5-HT reuptake, whereas the (-)-enantiomer is responsible for noradrenaline reuptake effects (Shipton, 2000). These actions appear to produce a synergistic analgesic effect, with (+)-tramadol exhibiting 10-fold higher analgesic activity than (-)-tramadol (Goeringer et al., 1997).

The serotonergic modulating properties of tramadol mean that it has the potential to interact with other serotonergic agents. There is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when tramadol is taken in combination with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. SSRIs) or with use of a light box, since these agents not only potentiate the effect of 5-HT but also inhibit tramadol metabolism. Tramadol is also thought to have some NMDA-type antagonist effects which has given it a potential application in neuropathic pain states.

[edit] Metabolism

Tramadol undergoes hepatic metabolism via the cytochrome P450 isozyme CYP2D6, being O- and N-demethylated to five different metabolites. Of these, M1 (O-Desmethyltramadol) is the most significant since it has 200 times the μ-affinity of (+)-tramadol, and furthermore has an elimination half-life of nine hours, compared with six hours for tramadol itself. In the 6% of the population who have slow CYP2D6 activity, there is therefore a slightly reduced analgesic effect. Phase II hepatic metabolism renders the metabolites water-soluble and they are excreted by the kidneys. Thus reduced doses may be used in renal and hepatic impairment.

[edit] Adverse effects and drug interactions

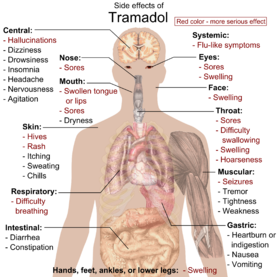

The most commonly reported adverse drug reactions are nausea, vomiting, sweating and constipation. Drowsiness is reported, although it is less of an issue than for opioids. Patients prescribed tramadol for general pain relief along with other agents have reported uncontrollable withdrawal-like nervous tremors if weaning off the medication happens too quickly. Respiratory depression, a common side effect of most opioids, is not clinically significant in normal doses. By itself, it can decrease the seizure threshold. When combined with SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, or in patients with epilepsy, the seizure threshold is further decreased. Seizures have been reported in humans receiving excessive single oral doses (700 mg) or large intravenous doses (300 mg). An Australian study found that of 97 confirmed new-onset seizures, eight were associated with Tramadol, and that in the authors' First Seizure Clinic, "Tramadol is the most frequently suspected cause of provoked seizures" (Labate 2005). Seizures caused by tramadol are most often tonic-clonic seizures, more commonly known in the past as grand mal seizures. Also when taken with SSRIs, there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome or serotonin storm. Dosages of coumadin/warfarin may need to be reduced for anticoagulated patients to avoid bleeding complications. Constipation can be severe especially in the elderly requiring manual evacuation of the bowel.[citation needed] Furthermore, there are suggestions that chronic opioid administration may induce a state of immune tolerance, [19] although Tramadol, in contrast to typical opioids may enhance immune function. [20][21][22] Some have also stressed the negative effects of opioids on cognitive functioning and personality. [23]

[edit] Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Tramadol is in FDA pregnancy category C; animal studies have shown its use to be dangerous during pregnancy and human studies are lacking. Therefore, the drug should not be taken by women who are pregnant unless "the potential benefits outweigh the risks".[24]

Tramadol causes serious or fatal[citation needed] side effects in a newborn, including neonatal withdrawal syndrome, if the mother uses the medication during pregnancy or labor. Use of tramadol by nursing mothers is not recommended by the manufacturer because the drug passes into breast milk.[24] However, the absolute dose excreted in milk is quite low, and tramadol is generally considered to be acceptable for use in breastfeeding mothers.[25]

[edit] Dependency

[edit] Physical dependence and withdrawal

Tramadol is associated with the development of a physical dependence and a withdrawal syndrome.[26] Tramadol causes typical opiate-like withdrawal symptoms as well as atypical withdrawal symptoms including seizures. The atypical withdrawal effects are probably related to tramadol's effect on serotonin and norepinephrin reuptake. Symptoms may include anxiety, anguish, pins and needles, sweating, and palpitations. It is recommended that patients physically dependent on pain killers take their medication regularly to prevent onset of withdrawal symptoms and when the time comes to discontinue their tramadol, to do so gradually over a period of time which will vary according to the individual patient and dose and length of time on the drug.[27][28][29][30]

[edit] Psychological dependence and drug misuse

Some controversy exists regarding the dependence/addiction liability of tramadol. Grünenthal has promoted it as an opioid with a lower risk of opioid dependence than that of traditional opioids, claiming little evidence of such dependence in clinical trials. They offer the theory that since the M1 metabolite is the principal agonist at μ-opioid receptors, the delayed agonist activity reduces dependence liability. The noradrenaline reuptake effects may also play a role in reducing dependence.

Studies into the dependence liability of tramadol show that patients are no more likely to abuse the drug than normal NSAIDs. Despite these claims, it is apparent in community practice that dependence to this agent may occur, but in higher doses and long-term usage.[31] However, this dependence liability is considered relatively low by health authorities, such that tramadol is classified as a Schedule 4 Prescription Only Medicine in Australia, rather than as a Schedule 8 Controlled Drug like opioids (Rossi, 2004). Similarly, tramadol is not currently scheduled by the U.S. DEA, unlike opioid analgesics. It is, however, scheduled in certain states.[32] Nevertheless, the prescribing information for Ultram warns that tramadol "may induce psychological and physical dependence of the morphine-type". A controlled study that compared different medications found "the percent of subjects who scored positive for abuse at least once during the 12-month follow-up were 2.5% for NSAIDs, 2.7% for tramadol, and 4.9% for hydrocodone. When more than one hit on the dependency algorithm was used as a measure of persistence, abuse rates were 0.5% for NSAIDs, 0.7% for tramadol, and 1.2% for hydrocodone. Thus, the results of this study suggest that the prevalence of abuse/dependence over a 12-month period in a CNP population that was primarily female was equivalent for tramadol and NSAIDs, with both significantly less than the rate for hydrocodone". This means that the abuse liability of tramadol was almost the same as that of normal NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen.[33]

However, due to the possibility of convulsions at high doses, recreational use is very dangerous.[34] Tramadol can however, via agonism of μ opioid receptors, produce effects similar to those of other opioids (e.g., morphine or hydrocodone), although not nearly as intense due to tramadol's much lower affinity for the receptor. However, the metabolite M1 is produced after demethylation of the drug in the liver. The M1 metabolite has an estimated 200x greater affinity for the μ1, and μ2 opioid receptors. In addition to acting as an opioid, tramadol is also a very weak but rapidly acting serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.[35] Tramadol can cause a higher incidence of nausea, dizziness, loss of appetite compared with opiates which could deter abuse to some extent.[36] Tramadol can help alleviate withdrawal symptoms from opiates, and it is much easier to lower the quantity of its usage, compared with opiates such as hydrocodone and oxycodone.[33] It may also have large effect on sleeping patterns. High doses may prevent sleeping.[37]

[edit] Animal treatment

Tramadol for animals is one of the most reliable and useful active principles available to veterinarians for treating animals in pain. It has a dual mode of action: mu agonism and monoamine reuptake inhibition, which produces mild anti-anxiety results. Tramadol may be utilized for relieving pain in cats and dogs. This is an advantage because the use of some non-steroidal anti-inflammatory substances in these animals may be dangerous.

When animals are administered tramadol, adverse reactions can occur. The most common are: constipation, upset stomach, decreased heart rate. In case of overdose, mental alteration, pinpoint pupils and seizures may appear. In such case, veterinarians should evaluate the correct treatment for these events. Some contraindications have been noted in treated animals taking certain other drugs. Tramadol should not be co-administered with Deprenyl or any other psychoactive ingredient such as: serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. In animals, tramadol is removed from the body via liver and kidney excretion. Animals suffering from diseases in these systems should be monitored by a veterinarian, as it may be necessary to adjust the dose.

Dosage and administration of tramadol for animals: in dogs a starting dosage of 1-2 mg/kg twice a day will be useful for pain management. Cats are administered 2-4 mg/kg twice a day.

[edit] Legal status

Tramadol is not considered a controlled substance in the US but is in Australia, and is available with a normal prescription. Tramadol is available over the counter without prescription in a few countries.[38] Sweden has, as of May 2008, chosen to classify Tramadol as a controlled substance in the same way as codeine and dextropropoxyphene. This means that the substance is a scheduled drug. But unlike codeine and dextropropoxyphene, a normal prescription can be used at this time.[5] As of December 5th, 2008, Kentucky has classified Tramadol as a C-IV controlled substance. [6] Tramadol is sometimes mistakenly classified as an opiate because of its agonist activity at the μ-opioid receptor; however, chemically it is not related to opiates.[39]

[edit] Proprietary preparations

Grünenthal, which still owns the patent to tramadol, has cross-licensed the agent to pharmaceutical companies internationally. Thus, tramadol is marketed under many trade names around the world, including:

|

|

|

|

[edit] References

- ^ Dayer P, Desmeules J, Collart L (1997). "[Pharmacology of tramadol]". Drugs 53 Suppl 2: 18–24. PMID 9190321.

- ^ PMID 9075493

- ^ [1]

- ^ Tramal, What is Tramal? About its Science, Chemistry and Structure

- ^ PMID 9749830

- ^ PMID 11565620

- ^ Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, et al (1998). "Double-blind randomized trial of tramadol for the treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy". Neurology 50 (6): 1842–46. PMID 9633738.

- ^ Harati Y, Gooch C, Swenson M, et al (2000). "Maintenance of the long-term effectiveness of tramadol in treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy". J. Diabetes Complicat. 14 (2): 65–70. PMID 10959067.

- ^ Göbel H, Stadler T (1997). "[Treatment of post-herpes zoster pain with tramadol. Results of an open pilot study versus clomipramine with or without levomepromazine]" (in French). Drugs 53 Suppl 2: 34–39. PMID 9190323.

- ^ Boureau F, Legallicier P, Kabir-Ahmadi M (2003). "Tramadol in post-herpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Pain 104 (1–2): 323–31. doi:. PMID 12855342.

- ^ Bennett RM, Kamin M, Karim R, Rosenthal N (2003). "Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study". Am. J. Med. 114 (7): 537–45. doi:. PMID 12753877.

- ^ Lauerma H, Markkula J (1999). "Treatment of restless legs syndrome with tramadol: an open study". The Journal of clinical psychiatry 60 (4): 241–44. PMID 10221285.

- ^ Sobey PW, Parran TV, Grey SF, Adelman CL, Yu J (2003). "The use of tramadol for acute heroin withdrawal: a comparison to clonidine". J Addict Dis 22 (4): 13–25. PMID 14723475.

- ^ Threlkeld M, Parran TV, Adelman CA, Grey SF, Yu J (2006). "Tramadol versus buprenorphine for the management of acute heroin withdrawal: a retrospective matched cohort controlled study". Am J Addict 15 (2): 186–91. doi:. PMID 16595358.

- ^ Engindeniz Z, Demircan C, Karli N, et al (June 2005). "Intramuscular tramadol vs. diclofenac sodium for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in emergency department: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study". J Headache Pain 6 (3): 143–48. doi:. PMID 16355295.

- ^ Goldsmith TB, Shapira NA, Keck PE (1999). "Rapid remission of OCD with tramadol hydrochloride". The American journal of psychiatry 156 (4): 660–61. PMID 10200754. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/156/4/660a.

- ^ Salem EA, Wilson SK, Bissada NK, Delk JR, Hellstrom WJ, Cleves MA (2007). "Tramadol HCL has Promise in On-Demand Use to Treat Premature Ejaculation". The Journal of Sexual Medicine (OnlineEarly Articles): 070314061909001. doi:. PMID 17362279.

- ^ "MedlinePlus Drug Information: Tramadol". http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a695011.html. Retrieved on 2009-02-07, Last Revised - 07/01/2007, Last Reviewed - 09/01/2008.

- ^ Bryant et al. 1988; Rouveix 1992; cited by Collet, B.-J. (2001) Chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 87 (1), 133-143.

- ^ Anesth Analg 2000;90:1411-1414 May also cause nerve response such as severe itching. © 2000 International Anesthesia Research Society The Effects of Tramadol and Morphine on Immune Responses and Pain After Surgery in Cancer Patients

- ^ Liu Z, Gao F, Tian Y. Department of Anesthesiology, Tongji Hospital, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430030, China. Effects of morphine, fentanyl and tramadol on human immune response.

- ^ Sacerdote P, Bianchi M, Manfredi B, Panerai AE. Department of Pharmacology, University of Milan, Italy. Effects of tramadol on immune responses and nociceptive thresholds in mice.

- ^ Maruta 1978; McNairy et al. 1984; cited by Collet, B.-J. (2001) Chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 87 (1), 133-143

- ^ a b [2]

- ^ United States National Library of Medicine

- ^ Barsotti, Ce; Mycyk, Mb; Reyes, J (January 2003). "Withdrawal syndrome from tramadol hydrochloride". The American journal of emergency medicine 21 (1): 87–8. doi:. PMID 12563592.

- ^ Choong, K; Ghiculescu, Ra (August 2008). "Iatrogenic neuropsychiatric syndromes". Australian family physician 37 (8): 627–9. ISSN 0300-8495. PMID 18704211.

- ^ Ripamonti, C; Fagnoni, E; De, Conno, F (December 2004). "Withdrawal syndrome after delayed tramadol intake". The American journal of psychiatry 161 (12): 2326–7. doi:. PMID 15569913. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/161/12/2326.

- ^ "Withdrawal syndrome and dependence: tramadol too" (Free full text). Prescrire international 12 (65): 99–100. June 2003. ISSN 1167-7422. PMID 12825576. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search/r?dbs+hsdb:@term+@rn+22204-88-2.

- ^ Senay, Ec; Adams, Eh; Geller, A; Inciardi, Ja; Muñoz, A; Schnoll, Sh; Woody, Ge; Cicero, Tj (April 2003). "Physical dependence on Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride): both opioid-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms occur". Drug and alcohol dependence 69 (3): 233–41. doi:. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 12633909.

- ^ McDiarmid, Todd; Mackler, Leslie (2005-01-01). "What is the addiction risk associated with tramadol". Journal of Family Practice 54 (1). http://www.jfponline.com/Pages.asp?AID=1849. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

- ^ Kentucky Board of Pharmacy (2008-12-08). Tramadol Listed as Schedule IV Substance in Kentucky. Press release. http://pharmacy.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/9A7E27E4-1D37-4F44-A542-C9DD5B487822/0/TramadolNotification.pdf. Retrieved on 2009-02-08.

- ^ a b Adams, Edgar; Breiner, Scott; Cicero, Theodore; Geller, Anne; Inciardi, James; Schnoll, Sidney; Senay, Edward; Woody, George (May 2006). "A Comparison of the Abuse Liability of Tramadol, NSAIDs, and Hydrocodone in Patients with Chronic Pain" (PDF). Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 31 (5): 465–76. doi:. http://paincenter.wustl.edu/c/BasicResearch/documents/CiceroJPain2006.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-01-13.

- ^ Jovanović-Cupić, V; Martinović, Z; Nesić, N (2006). "Seizures associated with intoxication and abuse of tramadol". Clinical toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.) 44 (2): 143–6. ISSN 1556-3650. PMID 16615669.

- ^ King, Steven A. (2007-06-01). "NSAIDs and Cardiovascular Disease". Psychiatric Times 24 (7). http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/showArticle.jhtml?print=true&articleID=199703448. Retrieved on 2007-08-01.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rf; Bravo, Le; Castro, F; Montoya, O; Castillo, Jm; Castillo, Mp; Daza, P; Restrepo, Jm; Rodriguez, Mf (February 2007). "Incidence of weak opioids adverse events in the management of cancer pain: a double-blind comparative trial". Journal of palliative medicine 10 (1): 56–60. doi:. ISSN 1096-6218. PMID 17298254.

- ^ Vorsanger, Gj; Xiang, J; Gana, Tj; Pascual, Ml; Fleming, Rr (March 2008). "Extended-release tramadol (tramadol ER) in the treatment of chronic low back pain" (Free full text). Journal of opioid management 4 (2): 87–97. ISSN 1551-7489. PMID 18557165. http://symptomresearch.nih.gov/chapter_1/index.htm.

- ^ Erowid

- ^ [3]

[edit] External links

- Official Website

- Press release from Johnson & Johnson regarding tramadol/acetaminophen combination pill now available in Canada

- Drugs.com - Tramadol Consumer information

- American Pain Foundation

- TramadolInfo.com - Tramadol Information Extended source of information about Tramadol

- Tramadol entry at Erowid, a member-supported organisation claiming to provide reliable, non-judgmental information about psychoactive plants and chemicals

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||