Business process management

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Business process management (BPM) is a field of management focused on aligning organizations with the wants and needs of clients. It is a holistic management approach[citation needed] that promotes business effectiveness and efficiency while striving for innovation, flexibility and integration with technology. Business process management attempts to continuously improve processes. It could therefore be described as a "process optimization process".

[edit] Overview

A business process is "a collection of related, structured activities that produce a service or product that meet the needs of a client."[citation needed] These processes are critical to any organization as they generate revenue and often represent a significant proportion of costs. BPM articles and pundits often discuss BPM from one of two viewpoints: people and technology.

Roughly speaking, the idea of (business) process is as traditional as concepts of tasks, department, production, outputs. The current management and improvement approach, with formal definitions and technical modeling, has been around since the early 1990s (see business process modeling). However there has been a common confusion in the IT community, as the term 'business process' is often used as synonymous of management of middleware processes; or integrating application software tasks. This viewpoint may be overly restrictive. This should be kept in mind when reading software engineering papers which refer to 'business processes' or 'business process modeling.'

Although the initial focus of BPM was on the automation of mechanistic business processes, it has since been extended to integrate human-driven processes in which human interaction takes place in series or parallel with the mechanistic processes. A common form is where individual steps in the business process which require human intuition or judgment to be performed are assigned to the appropriate members of an organization (as with workflow systems).

More advanced forms such as human interaction management are in the complex interaction between human workers in performing a workgroup task. In this case many people and systems interact in structured, ad-hoc, and sometimes completely dynamic ways to complete one to many transactions.

BPM can be used to understand organizations through expanded views that would not otherwise be available to organize and present. These views include the relationships of processes to each other which, when included in the process model, provide for advanced reporting and analysis that would not otherwise be available. BPM is regarded by some as the backbone of enterprise content management.

[edit] History of BPM

[edit] The Three Business Process Traditions

Business Process Management, or BPM, broadly speaking, is part of management approach that is now several decades old. BPM aims at improving the way business people think about and manage their businesses. Its particular manifestations, whether they are termed “work simplification,” “six sigma,” “business process reengineering,” or “business process management,” may come and go, but the underlying impulse, to shift the way managers and employees think about the organization of business, continues to evolve.

The place to begin is with an overview of the world of business process change technologies and methodologies. In essence, there are three major process traditions: the management tradition, the quality control tradition, and the IT tradition. Too often individuals who come from one tradition are inclined to ignore or depreciate the other approaches, feeling that their approach is sufficient or superior. Today, however, the tendency is for three traditions to merging into a more comprehensive BPM tradition.

One could easily argue that each of the three traditions has roots that go right back to ancient times. Managers have always tried to make workers more productive, there have always been efforts to simplify processes and to control the quality of outputs, and, if IT is regarded as an instance of technology, then people have been trying to use technologies of one kind or another ever since the first human picked up a stick to use as a spear or a lever. All three traditions got a huge boost from the Industrial Revolution which started to change manufacturing at the end of the 18th Century. Our concern here, however, is not with the ancient roots of these traditions but the recent developments in each field and the fact that practitioners in one field often choose to ignore the efforts of those working in other traditions.

[edit] The Work Simplification\Quality Control Tradition

The Quality Control tradition as a continuation of the Work Simplification tradition. The modern roots of quality control and process improvement, in the United States, at least, date from the publication, by Frederick Winslow Taylor, of Principles of Scientific Management, in 1911 (Taylor, 1911). Taylor described a set of key ideas he believed good managers should use to improve their businesses. He argued for work simplification, for time studies, for systematic experimentation to identify the best way of performing a task, and for control systems that measured and rewarded output. Taylor’s book became an international best-seller and has influenced many in the process movement. Shigeo Shingo, one of the co-developers of the Toyota Production System, describes how he first read a Japanese translation of Taylor in 1924 and the book itself in 1931 and credits it for setting the course of his work life (Shingo, 1983)

One must keep in mind, of course, the Taylor wrote immediately after Henry Ford introduced his moving production line and revolutionized how managers thought about production. The first internal-combustion automobiles were produced by Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler in Germany in 1885. In the decades that followed, some 50 entrepreneurs in Europe and North America set up companies to build cars. In each case, the companies built cars by hand, incorporating improvements with each model. Henry Ford was one among many who tried his hand at building cars in this manner (McGraw, 1997).

In 1903, however, Henry Ford started his third company, the Ford Motor Company, and tried a new approach to automobile manufacturing. First, he designed a car that would be of high quality, not too expensive, and easy to manufacture. Next he organized a moving production line. In essence, workmen began assembling a new automobile at one end of the factory building and completed the assembly as it reached the far end of the plant. Workers at each point along the production line had one specific task to do. One group moved the chassis into place, another welded on the side panels, and still another group lowered the engine into place when each car reached their station. In other words, Henry Ford conceptualized the development of an automobile as a single process and designed and sequenced each activity in the process to assure that the entire process ran smoothly and efficiently. Clearly Ford had thought deeply about the way cars were assembled in his earlier plants and had a very clear idea of how he could improve the process.

By organizing the process as he did, Henry Ford was able to significantly reduce the price of building automobiles. As a result, he was able to sell cars for such a modest price that he made it possible for every middle-class American to own a car. At the same time, as a direct result of the increased productivity of the assembly process, Ford was able to pay his workers more than any other auto assembly workers. Within a few years, Ford’s new approach had revolutionized the auto industry, and it soon led to changes in almost every other manufacturing process as well. This success had managers throughout the world scrambling to learn about Ford’s innovations and set the stage for the tremendous popularity of Taylor’s book which seemed to explain what lay behind Ford’s achievement.

Throughout the first half of the 20th Century, engineers worked to apply Taylor’s ideas, analyzing processes, measuring and applying statistical checks whenever they could. Ben Graham, in his book on Detail Process Charting, describes the Work Simplification movement during those years, and the annual Work Simplification conferences, sponsored by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME), that were held in Lake Placid, New York (Graham, 2004). These conferences, that lasted into Sixties, were initially stimulated by a 1911 conference at on Scientific Management, held at Dartmouth College, and attended by Taylor and the various individuals who were to dominate process work in North America during the first half of the 20th Century.

The American Society for Quality (ASQ) was established in 1946 and the Work Simplification movement gradually transitioned into the Quality Control movement. In 1951, Juran’s Quality Control Handbook appeared for the first time and this magisterial book has become established at the encyclopedic source of information about the quality control movement (Juran, 1951)

In the Eighties, when US auto companies began to lose significant market share to the Japanese, many began to ask what the Japanese were doing better. The popular answer was that the Japanese had embraced an emphasis on Quality Control that they learned, ironically, from Edwards Deming, a quality guru sent to Japan by the US government in the aftermath of World War II. (Deming’s classic book is Out of the Crisis, published in 1982.) In fact, of course the story is more complex, and includes the work of native Japanese quality experts, like Shigeo Shingo and Taiichi Ohno, who were working to improve production quality well before World War II, and who joined, in the post-war period to create the Toyota Production System, and thereby became the fathers of Lean (Shiegeo, 1983; Taiichi, 1978). (The work of Shingo and Ohno work was popularized in the US by James Womack, Daniel Jones and Daniel Roos in their book The Machine That Changed the World: The story of Lean Production, 1991. This book was a commissioned study of what Japanese auto manufacturing companies were doing and introduced “lean” into the process vocabulary.) The Baldrige National Quality Awards program was established by the US Commerce Department in 1987 to encourage companies to adopt quality control techniques (www.quality.nist.gov).

[edit] TQM, Lean and Six Sigma

In the Seventies the most popular quality control methodology was termed Total Quality Management (TQM), but in the late-Eighties it began to be superseded by Six Sigma – an approach developed at Motorola (Ramias, 2005; Barney, 2003). Six Sigma combined process analysis with statistical quality control techniques, and a program of organizational rewards and emerged as a popular approach to continuous process improvement. In 2001 the ASQ established a SIG for Six Sigma and began training black belts. Since then the quality movement has gradually been superseded, at least in the US, by the current focus on Lean and Six Sigma.

Many readers may associate Six Sigma and Lean with specific techniques, like DMAIC, Just-In-Time (JIT) delivery, or the Seven Types of Waste, but, in fact, they are just as well known for their emphasis on company-wide training efforts designed to make every employee responsible for process quality. One of the most popular executives in the US, Jack Welsh, who was CEO of General Electric when his company embraced Six Sigma, not only mandated a company-wide Six Sigma effort, but made 40% of every executive’s bonus dependent on Six Sigma results. Welch went on to claim it was the most important thing he did while he was CEO of GE. In a similar way, Lean, in its original implementation as the Toyota Production System, is a company-wide program embraced with an almost religious zeal by the CEO and by all Toyota’s managers and employees. Of all the approaches to process improvement, Lean and Six Sigma come closest, at their best, in implementing an organizational transformation that embraces process throughout the organization.

Throughout most of the Nineties, Lean and Six Sigma were offered as independent methodologies, but starting in this decade, companies have begun to combine the two methodologies and tend, increasingly, to refer to the approach as Lean Six Sigma.

[edit] Capability Maturity Model

An interesting example of a more specialized development in the Quality Control tradition is the development of the Capability Maturity Model (CMM) at the Software Engineering Institute (SEI) at Carnegie Mellon University. In the early Nineties, the US Defense of Department (DoD) was concerned about the quality of the software applications being delivered, and the fact that, in many cases, the software applications were incomplete and way over budget. In essence, the DoD asked Watts Humphrey and SEI to develop a way of evaluating software organizations to determine which were likely to deliver what they promised on time and within budget. Humphrey’s and his colleagues at SEI developed a model that assumed that organizations that didn’t understand their processes and that had no data about what succeeded or failed were unlike to deliver as promised. (Paulk, 1995) They studied software shops and defined a series of steps organizations went through as they become more sophisticated in managing the software process. In essence, the five steps or levels are as follows.

1.Initial – Processes aren’t defined.

2.Repeatable – Basic departmental processes are defined and are repeated more or less consistently.

3.Defined – The organization, as a whole, knows how all their processes work together and can perform them consistently.

4.Managed – Managers consistently capture data on their processes and use that data to keep processes on track.

5.Optimizing – Managers and team members continuously work to improve their processes.

Level 5, as described by CMM, is nothing less that the company-wide embrace of process quality that we see at Toyota and at GE.

Once CMM was established, SEI proceeded to gathered large amounts of information on software organizations and begin to certify organizations as being level 1, 2, etc. and the DoD began to require level 3, 4 or 5 for their software contracts. The fact that several Indian software firms were able to establish themselves as CMM Level 5 organizations is often credited with the recent, widespread movement to outsource software development to Indian companies.

Since the original SEI CMM approach was defined in 1995, it has gone through many changes. At some point there were several different models, and, recently, SEI has made an effort to pull all of the different approaches back together and have called the new version CMMI – Capability Maturity Model Integrated. At the same time, SEI has generalized the model so that CMMI extends beyond software development and can be used to describe entire companies and their overall process maturity. (Chrissis, 2007) We will consider some new developments in this approach, later, but suffice to say here that CMMI is very much in the Quality Control tradition with it emphasis on output standards and statistical measures of quality.

If one considers all of the individuals working in companies who are focused on quality control, in all its variations like Lean and Six Sigma, they surely constitute the largest body of practitioners working for process improvement today.

[edit] The Management Tradition

At this point, we’ll leave the Quality Control tradition, whose practitioners have mostly been engineers and quality control specialists, and turn to the management tradition. As with the quality control tradition, it would be easy to trace the Management Tradition to Ford and Taylor. And, as we have already suggested, there have always been executives who have been concerned with improving how their organizations functioned. By the mid-Twentieth Century however, most US managers were trained at business schools that didn’t emphasize a process approach. Most business schools are organized along functional lines, and consider Marketing, Strategy, Finance, and Operations as separate disciplines. More important, operations have not enjoyed as much attention at business schools in the past decade.

Joseph M. Juran, in an article on the United States in his Quality Control Handbook, argues that the US emerged from World War II with its production capacity in good condition while the rest of the world was in dire need of manufactured goods of all kinds. (Juran, 1951) Thus, during the 50s and 60s US companies focused on producing large quantities of goods to fulfill the demand of consumers who weren’t very concerned about quality. Having a CEO who knew about finance or marketing was often considered more important than having a CEO who knew about operations. It was only in the Eighties, when the rest of the world had caught up with the US and began to offer superior products for less cost that things began to change. As the US automakers began to lose market share to quality European and Japanese cars in the Eighties, US mangers began to refocus on operations and began to search for ways to reduce prices and improve production quality. At that point, they rediscovered, in Japan, the emphasis on process and quality that had been created in the US in the first half of the 20th Century. Unlike the quality control tradition, however, that focuses on the quality and the production of products; the management tradition has focused on the overall performance of the firm. The emphasis is on aligning strategy with the means of realizing that strategy, and on organizing and managing employees to achieve corporate goals.

[edit] Geary Rummler

The most important figure in the management tradition in the years since World War II, has been Geary Rummler, who began his career at the University of Michigan, at the very center of the US auto industry. Rummler derives his methodology from both a concern with organizations as systems and combines that with a focus on how we train, manage, and motivate employee performance. He began teaching courses at the University of Michigan in the Sixties where he emphasized the use of organization diagrams, process flowcharts to model business processes, and task analysis of jobs to determine why some employees perform better than others. Later, Rummler joined with Alan Brache to create Rummler-Brache, a company that trained large numbers of process practitioners in the Eighties and early Nineties and co-authored, with Alan Brache, one of the real classics of our field – Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart. (Rummler, 1990) Rummler always emphasized the need to improve corporate performance, and argued that process redesign was the best way to do that. He then proceeded to argue that improving managerial and employee job performance was the key to improved processes.

Unlike the work simplification and quality control literature that was primarily read by engineers and quality control experts, Rummler’s work has always been read by business managers and human resource experts.

[edit] Michael Porter

A second important guru in the Management tradition is Harvard Business School professor Michael Porter. Porter was already established as a leading business strategy theorist, but in his 1985 book, Competitive Advantage, he moved beyond strategic concepts, as they had been described until then, and argued that strategy was intimately linked with how companies organized their activities into value chains, which were, in turn, the basis for a company’s competitive advantage. (Porter, 1985)

A Value Chain supports a product line, a market, and its customers. If your company produces jeeps, then you have a Value Chain for jeeps. If you company makes loans, then you have a Value Chain for loans. A single company can have more than one value chain. Large international organizations typically have from 5-10 value chains. In essence, value chains are the ultimate processes that define a company. All other processes are defined by relating them to the value chain. Put another way, a single value chain can be decomposed into major operational process like Market, Sell, Produce, and Deliver and associated management support processes like Plan, Finance, HR and IT. In fact, it was Porter’s value chain concept that emphasized the distinction between core and support processes. The value chain has been the organizing principle that has let organizations define and arrange their processes and structure their process change efforts during the past two decades.

As Porter defines it, a competitive advantage refers to a situation in which one company manages to dominate an industry for a sustained period of time. An obvious example, in our time, is Wal-Mart, a company that completely dominates retail sales in the US and seems likely to continue to do so for the foreseeable future. “Ultimately,” Porter concludes, “all differences between companies in cost or price derive from the hundreds of activities required to create, produce, sell, and deliver their products or services such as calling on customers, assembling final products, and training employees…” In other words, “activities... are the basic units of competitive advantage.” This conclusion is closely related to Porter’s analysis of a value chain. A value chain consists of all the activities necessary to produce and sell a product or service. Today we would probably use the word “processes” rather than “activity,” but the point remains the same. Companies succeed because they understand what their customers will buy and proceed to generate the product or service their customers want by means of a set of activities that create, produce, sell and deliver the product or service.

So far the conclusion seems like a rather obvious conclusion, but Porter goes further. He suggests that companies rely on one of two approaches when they seek to organize and improve their activities or processes. They either rely on an approach which Porter terms “operational effectiveness” or they rely on “strategic positioning.” “Operational effectiveness,” as Porter uses the term, means performing similar activities better than rivals perform them. In essence, this is the “best practices” approach we hear so much about. Every company looks about, determines what appears to be the best way of accomplishing a given task and then seeks to implement that process in their organization. Unfortunately, according to Porter, this isn’t an effective strategy. The problem is that everyone else is also trying to implement the same best practices. Thus, everyone involved in this approach gets stuck on a treadmill, moving faster all the time, while barely managing to keep up with their competitors. Best practices don’t give a company a competitive edge – they are too easy to copy. Everyone who has observed companies investing in software systems that don’t improve productivity or price but just maintain parity with one’s competitors understands this. Worse, this approach drives profits down because more and more money is consumed in the effort to copy the best practices of competitors. If every company is relying on the same processes then no individual company is in a position to offer customers something special for which they can charge a premium. Everyone is simply engaged in an increasingly desperate struggle to be the low cost producer, and everyone is trying to get there by copying each others best practices while their margins continue to shrink. As Porter sums it up: “Few companies have competed successfully on the basis of operational effectiveness over an extended period, and staying ahead of rivals gets harder every day.”

The alternative is to focus on evolving a unique strategic position and then tailoring the company’s value chain to execute that unique strategy. “Strategic positioning,” Porter explains, “means performing different activities from rivals’ or performing similar activities in different ways.” He goes on to say that “While operational effectiveness is about achieving excellence in individual activities, or functions, strategy is about combining activities.” Indeed, Porter insists that those who take strategy seriously need to have lots of discipline, because they have to reject all kinds of options to stay focused on their strategy.

Rounding out his argument, Porter concludes “Competitive advantage grows out of the entire system of activities. The fit among activities substantially reduces cost or increases differentiation.” He goes on to warn that “Achieving fit is difficult because it requires the integration of decisions and actions across many independent subunits.” Obviously we are just providing the barest summary of Porter’s argument. In essence, however, it is a very strong argument for defining a goal and then shaping and integrating a value chain to assure that all the processes in the value chain work together to achieve the goal.

The importance of this approach, according to Porter, is derived from the fact that “Positions built on systems of activities are far more sustainable than those built on individual activities.” In other words, while rivals can usually see when you have improved a specific activity, and duplicate it, they will have a much harder time figuring out exactly how you have integrated all your processes. They will have an even harder time duplicating the management discipline required to keep the integrated whole functioning smoothly.

Porter’s work on strategy and value chains assured that most modern discussion of business strategy are also discussions of how value chains or processes will be organized. This, in turn, has led to a major concern with how a company aligns its strategic goals with its specific processes and many of the current concerns we discuss in the following pages represent efforts to address this issue.

[edit] Balanced Scorecard

One methodology very much in the management tradition is the Balanced Scorecard methodology developed by Robert S. Kaplan and David P. Norton. (Kaplan, 1996) Kaplan and Norton began by developing an approach to performance measurement that emphasized a scorecard that considers a variety of different metrics of success. At the same time, the Scorecard methodology proposed a way of aligning departmental measures and managerial performance evaluations in hierarchies that could systemize all of the measures undertaken in an organization. Later they linked the scorecard with a model of the firm that stressed that people make processes work, that processes generated happy customers, and that happy customers generated financial results. (Kaplan, 2004) In other words, Kaplan and Norton have created a model that begins with strategy, links that to process and people, and then, in turn, links that to measures that determine if the operations are successfully implementing the strategy.

In its initial use, the Balanced Scorecard methodology was often used by functional organizations, but there are now a number of new approaches that tie the scorecard measures directly to value chains and business processes, and process people are increasingly finding the scorecard approach a systematic way to align process measures from specific activities to strategic goals.

[edit] Business Process Frameworks

Another development very much in the management tradition is the Supply Chain Council and its SCOR framework. The Supply Chain Council is a consortium of some 1000 companies. Attendees at SCC conferences, who meet throughout the world each year, are almost entirely senior supply chain managers. These are individuals who are interested in how companies supply chains work and how they can be combined with the supply chains of partners and distributors to achieve maximum results and efficiencies. In 1996 the SCC began to publish information about its Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) framework. The SCOR framework describes a supply chain in terms of three high level processes: Source, Make and Deliver, which it then subdivides into subprocesses. The framework defines measures for each process and subprocess and describes best practices used with each. (www.supply-chain.org)

A similar development occurred at the TeleManagement Forum, a consortium of Telecom executives. In 1997 the TMForum introduced its Telecom Operations Model (TOM), which has been extended to be the eTOM model. The business process framework provides a complete framework for all of the business processes used at a Telecom company. (www.tmforum.org)

Even more recently the Value Chain Group (VCG) has released a Value Reference Model (VRM) that provides generic processes capable of describing an entire value chain. (www.value-chain.org) The key thing to note about SCC, TMForum and VCG efforts is that they are driven by business executives who are interested in rapidly defining the processes and metrics for their organizations. In all three cases, best practices are more likely to describe management and employee practices than to consider software issues.

[edit] Business Process Reengineering

One can argue about where the Business Process Reengineering (BPR) movement should be placed. Some would place it in the management tradition because it motivated lots of senior executives to rethink their business strategies. The emphasis in BPR on value chains certainly derives from Porter. Others would place it in the IT tradition because it emphasized using IT to redefine work processes and automate them wherever possible. It probably sits on line between the two traditions, and we’ll consider in more detail under the IT tradition.

[edit] The Information Technology Tradition

The third tradition involves the use of computers and software applications to automate work processes. This movement began in the late Sixties and grew rapidly in the Seventies with an emphasis on automating back office operations like book keeping and record keeping and has progressed to the automation of a wide variety of jobs, either by doing the work with computers, or by providing desktop computers to assist humans in performing their work.

When Rummler began to work on process redesign in the late Sixties, he never considered automation. It was simply too specialized. Instead, all of his engagements involved straightening out the flow of the process and then working to improve how the managers and employees actually implemented the process. That continued to be the case through the early part of the Seventies, but began to change in the late Seventies as more and more core processes, at production facilities and in document processing operations, began to be automated.

We will not attempt to review the rapid evolution of IT systems, from mainframes to minis to PCs, or the way IT moved from the back office to the front office. Suffice to say that, for those who lived through it, computers seemed to come from nowhere and within two short decades, completely changed the way we think about the work and the nature of business. Today, it is hard to remember what the world was like without computer systems. And that it all happened in about 40 years. Perhaps the most important change, to date, occurred in 1995 when the Internet and the Web began to radically alter the way customers interacted with companies. In about two years we transitioned from thinking about computers as tools for automating internal business processes to thinking of them as a communication media that facilitated radically new business models. The Internet spread computer literacy throughout the entire population of developed countries and has forced every company to reconsider how its business works. And it is now driving the rapid and extensive outsourcing of processes and the worldwide integration of business activities.

The IT tradition is the youngest, and also the most complex tradition to describe in a brief way. Prior to the beginning of the Nineties, there was lots of work that focused on automating processes, but it was rarely described as process work, but rather referred as software automation. As it proceeded jobs were changed or eliminated and companies became more dependent on processes, but in spite of lots of arguments about how IT supported business, IT largely operated independently of the main business and conceptualized itself as a service.

[edit] Business Process Reengineering

That changed at the beginning of the Nineties with Business Process Reengineering (BPR), which was kicked off, more or less simultaneously, in 1990, by two articles: Michael Hammer’s “Reengineering Work: Don’t Automate, Obliterate” (Harvard Business Review, July/August 1990) and Thomas Davenport and James Short’s “The New Industrial Engineering: Information Technology and Business Process Redesign” (Sloan Management Review, Summer 1990). Later, in 1993, Davenport wrote a book, Process Innovation: Reengineering Work through Information Technology, and Michael Hammer joined with James Champy to write Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution.

Champy, Davenport, and Hammer insisted that companies must think in terms of comprehensive processes, similar to Porter’s value chains and Rummler’s Organization Level. If a company focused only on new product development, for example, the company might improve the new product development subprocess, but it might not improve the overall value chain. Worse, one might improve new product development process at the expense of the overall value chain. If, for example, new process development instituted a system of checks to assure higher-quality documents, it might produce superior reports, but take longer to produce them, delaying marketing and manufacturing’s ability to respond to sudden changes in the marketplace. Or the new reports might be organized in such a way that they made better sense to the new process development engineers, but became much harder for marketing or manufacturing readers to understand. In this sense, Champy, Davenport, and Hammer were very much in the Management Tradition.

At the same time, however, these BPR gurus argued that the major force driving changes in business was IT. They provided numerous examples of companies that had changing business processes in an incremental manner, adding automation to a process in a way that only contributed an insignificant improvement. Then they considered examples in which companies had entirely reconceptualized their processes, using the latest IT techniques to allow the process to function in a radically new way. In hindsight, BPR began our current era, and starting at that point, business people began to accept that IT was not simply a support process that managed data, but a radical way of transforming the way processes were done, and henceforth, an integral part of every business process.

BPR has received mixed reviews. Hammer, especially, often urged companies to attempt more than they reasonably could. Thus, for example, several companies tried to use existing technologies to pass information about their organizations and ended up with costly failures. Keep in mind these experiments were taking place in 1990-1995, before most people knew anything about the Internet. Applications that were costly and unlikely to succeed in that period, when infrastructures and communication networks were all proprietary became simple to install once companies adopted the Internet and learned to use email and web browsers. Today, even though many might suggest that BPR was a failure, its prescriptions have largely been implemented. Whole industries, like book and music retailers and newspapers are rapidly going out of business while customers now use online services to identify and acquire books, download music and provide the daily news. Many organizations have eliminated sales organizations and retail stores and interface with their customers online. And processes that were formerly organized separately are now all available online, allowing customers to rapidly move from information gathering, to pricing, to purchasing.

Much more important, for our purposes, is the change in attitude on the part of today’s business executives. Almost every executive today uses a computer and is familiar with the rapidity with which software is changing what can be done. Video stores have been largely replaced by services that deliver movies via mail, directly to customers. But the very companies that have been created to deliver movies by mail are aware that in only a few years movies will be downloaded from servers and their existing business model will be obsolete. In other words, today’s executives realize that there is no sharp line between the company’s business model and what the latest information technology will facilitate. IT is no longer a service – it has become the essence of the company’s strategy. Companies no longer worry about reengineering major processes and are more likely to consider getting out of an entire line of business and jumping into an entirely new line of business to take advantage of an emerging development in information or communication technology.

[edit] Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) Applications

By the late Nineties, most process practitioners would have claimed to have abandoned BPR, and were focusing, instead on more modest process redesign projects. Davenport wrote Mission Critical, a book that suggested that Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) applications could solve lots of process problems, and by the end of the decade most large companies had major ERP installation projects underway. (Davenport, 2000) ERP solved some problems and created others. Meanwhile, workflow applications also came into the own in the late Nineties, helping to automate lots of document processing operations. (Aalst, 2000)

[edit] CASE and Process Modeling Tools

The interest in Computer Aided Software Engineering (CASE) tools, originally created in the Eighties to help software engineers create software from the diagrams created by software developers using structured methodologies, declined, rapidly in the early Nineties as companies embraced minis, PCs and a variety on non-COBOL development languages and new object-oriented development methodologies. (McClure, 1989) The CASE vendors survived, however, by redesigning their tools and repositioning themselves as business process modeling tools. Thus, as companies embraced BPR in the mid-Nineties they did it, in part, by teaching business people to use modeling tools to better understand their processes. (Scheer, 1994)

[edit] Expert Systems and Business Rules

In a similar way, software developed to support Expert Systems development in the Eighties morphed into business rule tools in the Nineties. The expert systems movement failed, not because it was impossible to capture the rules that human experts used to analyze and solve complex problems, but because it was impossible to maintain the expert systems once they were developed. To capture the rules used by a physician to diagnose a complex problem required tens of thousands of rules. Moreover the knowledge kept changing and physicians needed to keep reading and attending conferences to stay up-to-date. (Harmon, 1985, 1993) As the interest in expert systems faded, however, others noticed that small systems designed to help mid-level employees perform tasks were much more successful. Even more successful were systems designed to see that policies were accurately implemented throughout the organizations. (Ross, Gradually, companies in industries like insurance and banking established business rule groups to develop and maintain systems that enforced policies implemented in their business processes. Processes analysis and business rule analysis have not yet fully merged, but everyone now realizes that they are two sides of the same coin. As a process is executed, decisions are made. Many of those decisions can be described in terms of business rules. By the same token, no one wants to deal with huge rule bases, and process models provide an ideal way to structure where and how business rules will be used.

[edit] Business Process Management Systems

The main development within the IT movement during the decade, however, has been Business Process Management Systems (BPMS). In essence, BPMS is more a concept than a well-defined technology. Howard Smith and Peter Fingar defined a BPMS approach in their book, Business Process Management: The Third Wave. (Smith, 1983). They argued that the Internet and Internet Protocols like XML made it possible for companies to combine traditional workflow and Enterprise Application Integration (EAI) approaches to create a tool that would let business managers model and edit their own business processes. Their argument, like the claims of Hammer, Champy, and Davenport, a decade earlier, were ahead of reality, but what they propose will probably come about in the course of the next decade. In the meantime, workflow and EAI vendors began to acquire each other and offer new BPMS products. The best of these tools make it possible for software savvy business process analysts to capture business processes in models, automate them, and later modify them. In fact, however, there have been few applications developed, to date, that really fulfill Smith and Fingar’s ideal. Most of the “BPMS” systems developed, to date, are really workflow or EAI applications that could have been developed 5-10 years ago. They were developed by IT developers, not business managers, and they will be maintained by IT professionals.

Meanwhile, the concept of BPMS has grown, and now embraces business rules, simulation, business intelligence and executive dashboards, groupware, and SOA. In essence, vendors are struggling to pull together all of the software techniques available into a single business process management platform. To date, more emphasis has been placed on integrating software techniques than on building an interface that business managers can use. Eventually, however, someone will get there, probably by building an industry specific application-building tool – for example a BPMS product for the creation and management of call centers, or a BPMS tool for the development of insurance applications. (Miers, 2005)

A more interesting issue is how the relationship between BPMS products and ERP applications will evolve. ERP vendors like SAP, Oracle, and Microsoft have been active in the BPMS arena, and BPMS vendors have created lots of applications that, in essence, manage a set of ERP modules. It is likely that BPMS will be integrated with ERP to provide managers with more flexible ERP systems that are easier to manage.

[edit] BPMN, BPEL and Other Standards

A consortium set up to promote BPMS use, BPMI, created a business process notation, the Business Process Management Notation (BPMN) which has been widely adopted. BPMI has since merged with the Object Management Group (OMG), a major standards organization, which is now doing what standards organizations do to assure that BPMN is open and maintained. Another standards group OASIS is working to formalize a Business Process Execution Language (BPEL) and that work is going slowly. In the long run, perhaps, BPEL will be used to provide a standard underpinning for BPMS products, but it won’t happen soon. Meanwhile there are a variety of other standards initiatives underway to facilitate standardization and communication among BPMS products that may bear fruit in the next decade.

[edit] Process and the Interface Between Business and IT

Stepping back from all the specific software initiatives, there is a new spirit in IT. Executives are more aware than ever of the strategic value of computer and software technologies and seek to create ways to assure that their organizations remain current. IT is aware that business executives often perceive that IT is focused on technologies rather than on business solutions. Both executives and IT managers hope that a focus on process will provide a common meeting ground. Business executives can focus on creating business models and processes that take advantage of the emerging opportunities in the market. At the same time, IT architects can focus on business processes and explain their new initiatives in terms of improvements they can make in specific processes. If business process management platforms can be created to facilitate this discussion, that will be very useful. But even without software platforms, process seems destined to play a growing role in future discussions between business and IT managers.

One key to assuring that the process-based discussions that business and IT managers engage in are useful is to assure that both begin with a comprehensive understanding of process. A process that is limited to what can be automated with today’s techniques is too limited to facilitate useful discussions. Business executives are concerned with broader views of what a process entails. While it is impossible, today, to think of undertaking a major business process redesign project without considering what information technology can do to improve the process, at the same time, considering how employees and managers will perform to assure customer satisfaction. Employees and the management of employees are just as important as information technology and we need, more than ever, an integrated, holistic approach to the management of process change.

Business Process Management is a generic term that is used by each of the traditions described in slightly different ways. Very broadly, BPM is simply an effort on the part of today’s organizations to get control of the various efforts being undertaken to change and manage business processes. Different companies, depending on which traditions have been prevalent there in the past will approach BPM in different ways.

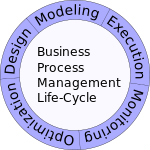

[edit] BPM life-cycle

The activities which constitute business process management can be grouped into five categories: design, modeling, execution, monitoring, and optimization.

[edit] Design

Process Design encompasses both the identification of existing processes and the design of "to-be" processes. Areas of focus include: representation of the process flow, the actors within it, alerts & notifications, escalations, Standard Operating Procedures, Service Level Agreements, and task hand-over mechanisms.

Good design reduces the number of problems over the lifetime of the process. Whether or not existing processes are considered, the aim of this step is to ensure that a correct and efficient theoretical design is prepared.

The proposed improvement could be in human to human, human to system, and system to system workflows, and might target regulatory, market, or competitive challenges faced by the businesses.

[edit] Modeling

Modeling takes the theoretical design and introduces combinations of variables, for instance, changes in the cost of materials or increased rent, that determine how the process might operate under different circumstances.

It also involves running "what-if analysis" on the processes: "What if I have 75% of resources to do the same task?" "What if I want to do the same job for 80% of the current cost?"

[edit] Execution

One of the ways to automate processes is to develop or purchase an application that executes the required steps of the process; however, in practice, these applications rarely execute all the steps of the process accurately or completely. Another approach is to use a combination of software and human intervention; however this approach is more complex, making the documentation process difficult.

As a response to these problems, software has been developed that enables the full business process (as developed in the process design activity) to be defined in a computer language which can be directly executed by the computer. The system will either use services in connected applications to perform business operations (e.g. calculating a repayment plan for a loan) or, when a step is too complex to automate, will ask for human input. Compared to either of the previous approaches, directly executing a process definition can be more straightforward and therefore easier to improve. However, automating a process definition requires flexible and comprehensive infrastructure, which typically rules out implementing these systems in a legacy IT environment.

Business rules have been used by systems to provide definitions for governing behavior, and a business rule engine can be used to drive process execution and resolution.

[edit] Monitoring

Monitoring encompasses the tracking of individual processes, so that information on their state can be easily seen, and statistics on the performance of one or more processes can be provided. An example of the tracking is being able to determine the state of a customer order (e.g. ordered arrived, awaiting delivery, invoice paid) so that problems in its operation can be identified and corrected.

In addition, this information can be used to work with customers and suppliers to improve their connected processes. Examples of the statistics are the generation of measures on how quickly a customer order is processed or how many orders were processed in the last month. These measures tend to fit into three categories: cycle time, defect rate and productivity.

The degree of monitoring depends on what information the business wants to evaluate and analyze and how business wants it to be monitored, in real-time or ad-hoc. Here, business activity monitoring (BAM) extends and expands the monitoring tools in generally provided by BPMS.

Process mining is a collection of methods and tools related to process monitoring. The aim of process mining is to analyze event logs extracted through process monitoring and to compare them with an 'a priori' process model. Process mining allows process analysts to detect discrepancies between the actual process execution and the a priori model as well as to analyze bottlenecks.

[edit] Optimization

Process optimization includes: retrieving process performance information from modeling or monitoring phase; identifying the potential or actual bottlenecks and the potential opportunities for cost savings or other improvements; and then, applying those enhancements in the design of the process. Overall, this creates greater business value.

[edit] Practice

Whilst the steps can be viewed as a cycle, economic or time constraints are likely to limit the process to one or more iterations.

In addition, organizations often start a BPM project or program with the objective to optimize an area which has been identified as an area for improvement.

In financial sector, BPM is critical to make sure the system delivers a quality service while maintaining regulatory compliance.[2]

Currently, the international standards for the task have only limited to the application for IT sectors and ISO/IEC 15944 covers the operational aspects of the business. However, some corporations with the culture of best practices do use standard operating procedures to regulate their operational process [3]

[edit] BPM Technology

BPM System (BPMS) is sometimes seen as "the whole of BPM." Some see that information moves between enterprise software packages and immediately think of Service Oriented Architecture (SOA). Others believe that "modeling is the only way to create the ‘perfect’ process," so they think of modeling as BPM.

Both of these concepts go into the definition of Business Process Management. For instance, the size and complexity of daily tasks often requires the use of technology to model efficiently. Some people view BPM as "the bridge between Information Technology (IT) and Business."

BPMS can be industry-specific, and might be driven by a specific software package such as Agilent OpenLAB BPM. Other products may focus on Enterprise Resource Planning and warehouse management.

Validation of BPMS is another technical issue which vendors and users need to be aware of, if regulatory compliance is mandatory.[4] The validation task could be performed either by an authenticated third party or by the users themselves. Either way, validation documentation will need to be generated. The validation document usually can either be published officially or retained by users[5]

[edit] Use of software

Some say that "not all activities can be effectively modeled with BPMS, and so, some processes are best left alone."[who?] Taking this viewpoint, the value in BPMS is not in automating "very simple" or "very complex" tasks: it is to be found in modeling processes where there is the most opportunity.

The alternate view is that a complete process modeling language, supported by a BPMS, is needed. The purpose of this is not purely "automation to replace manual tasks," but rather "to enhance manual tasks with computer assisted automation." In this sense, the argument over whether BPM is about "replacing human activity with automation," or simply, "analyzing for greater understanding of process," is a sterile debate. All processes that are modeled using BPMS must be executable in order to "bring to life" the software application that the human users interact with at run time.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ NIH (2007). Business Process Management (BPM) Service Pattern. Accessed 29 Nov 2008.

- ^ Oracle.com Business Process Management in the Finance Sector. Accessed 16 July 2008.

- ^ NTAID (2008). Invoice Processing Procedures for Contracts Accessed 17 Sept 2008.

- ^ FDA Guidance for Industry : Part 11, Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures - Scope and Application. Accessed 16 March 2008.

- ^ Mettler ToledoEfficient system validation. Accessed 17 march 2008.

[edit] Further reading

- James F. Chang (2006). Business Process Management Systems. ISBN 0-8493-2310-X

- Roger Burlton (2001). Business Process Management: Profiting From Process. ISBN 0-672-32063-0

- Jean-Noël Gillot (2008). The complete guide to Business Process Management. ISBN 978-2-9528-2662-4

- Paul Harmon (2007). "Business Process Change: 2nd Ed. A Guide for Business Managers and BPM and Six Sigma Professionals". Morgan Kaufmann ISBN 978-0-12-374152-3

- Keith Harrison-Broninski (2005). Human Interactions: The Heart and Soul of Business Process Management ISBN 0-929652-44-4

- John Jeston and Johan Nelis (2006) Business Process Management: Practical Guidelines to Successful Implementations ISBN 0-7506-6921-7

- Martyn Ould (2005). Business Process Management: A Rigorous Approach. ISBN 1-902505-60-3

- Howard Smith, Peter Fingar (2003). Business Process Management: The Third Wave.

- Andrew Spanyi (2003). Business Process Management Is a Team Sport: Play It to Win! ISBN 0-929652-02-3

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Business process management |

- The Process Wiki A repository (wiki) for all kinds of business processes

- BPTrends Website A free webizine that publishes artices on all aspects of business process management

- Early Aspects for Business Process Modeling (An Aspect Oriented Language for BPMN)

- Practice of innovative usage of BPMS in corporations