Yahweh

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can request an edit, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

- For more information about the name of the deity in Judaism and Christianity (Yahweh), see criticisms and theories on Yahweh or God in Abrahamic religions, which provides useful links.

Yahweh is the English rendering of יַהְוֶה, a vocalization of the Tetragrammaton יהוה that was proposed by the Hebrew scholar Gesenius in the 19th century. The stem of the name Yahweh (Yah-) remains widely accepted but disagreements continue on the ending (-weh). This pronunciation and spelling, as with many religious and scholarly issues, remains the subject of ongoing debate[1].

The 7th-11th century Masoretic Text vocalises the Hebrew term יהוה as יְהֹוָה (YeHoWah/JeHoVaH). The Masoretic text underlies the Old Testament of the most circulated Bible of the Christian world, the King James Version, as well as many of the other English language versions. However, this vocalization had been disputed by Hebrew scholars from as early as 1604 A.D. In the 19th century, the Jehovah vocalisation was finally rejected by major Hebrew scholars, who did not believe that it accurately represented the original pronunciation[2]; based on Epiphanius's Greek transcription Ιαβε (representing Yave) of a term used by some Gnostic circles, Gesenius proposed יַהְוֶה as the correction[3]

Correct pronunciation and spelling

| It has been suggested that this section be split into a new article entitled Tetragrammaton (correct pronunciation). (Discuss) |

Correct pronunciation and spelling of the name has historically been a matter of some disagreement, and the consensus view at various points in history has not been consistent.

Historical overview

Observant Jews write down but do not pronounce the Tetragrammaton, because it is considered too sacred to be used for common activities. Even ordinary prayer is considered too common for this use. The Tetragrammaton was pronounced by the High Priest on Yom Kippur when the Temple was standing in Jerusalem. Since the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, the Tetragrammaton is no longer pronounced, and while Jewish tradition holds that the correct pronunciation is known to a select few people in each generation, it is not generally known what this pronunciation is. Instead, common Jewish use has been to substitute the name "Adonai" ("My Lord") where the Tetragrammaton appears. In cases where the Tetragrammaton follows the name Adonai in biblical texts, the name Elohim ("God") is substituted instead.

The Septuagint (Greek translation) and Vulgate (Latin translation) use the word "Lord" (κύριος (kurios) and dominus, respectively). However, newer research has brought to light the oldest available copies of the Septuagint which interestingly include the Tetragrammaton inside the Greek text.

The Masoretes added vowel points (niqqud) and cantillation marks to the manuscripts to indicate vowel usage and for use in the ritual chanting of readings from the Bible in synagogue services. To יהוה they added the vowels for "Adonai" ("My Lord"), the word to use when the text was read.

Many Jews will not even use "Adonai" except when praying, and substitute other terms, e.g. HaShem ("The Name") or the nonsense word Ado-Shem, out of fear of the potential misuse of the divine name. In written English, "G-d" is a substitute used by a minority of Christians.

Parts of the Talmud, particularly those dealing with Yom Kippur, seem to imply that the Tetragrammaton should be pronounced in several ways, with only one (not explained in the text, and apparently kept by oral tradition by the Kohen Gadol) being the personal name of God.

In late Kabbalistic works the Tetragrammaton is sometimes referred to as the Name of Havayah - הוי'ה, meaning "the Name of Being/Existence". Christian Kabbalists used the form Jehovah.

Translators often render YHWH as a word meaning "Lord", e.g. Greek Κυριος, Latin Dominus, and following that, English "the Lord", Polish Pan, Welsh Arglwydd, etc. However, all of the above are inaccurate translations of the Tetragrammaton.

Because the name was no longer pronounced and its own vowels were not written, its own pronunciation was forgotten. When Christians, unaware of the Jewish tradition, started to read the Hebrew Bible, they read יְהֹוָה as written with YHWH's consonants with Adonai's vowels, and thus said or transcribed Iehovah. Today this transcription is generally recognized as mistaken; however many religious groups continue to use the form Jehovah because it is familiar.

Using the Name in the Bible

Exodus 3:15 is used to support the use of the Name YHWH: “This is my Name forever, and this is my memorial to all generations.”. The word “forever” is “olahm” which means “time out of mind, to eternity”. "The Hebrew word ‘olahm’, translated ‘for ever’ clearly doesn’t always mean literal future infinity- although in some places it can have that sense. It’s actually used in places to describe the past; events of a long time ago, but not events that happened an ‘infinitely long time’ ago. It describes the time of a previous generation (Dt. 32:7; Job 22:15); to the time just before the exile of Judah (Is. 58:12; 61:4; Mic. 7:14; Mal. 3:4); to the time of the Exodus (1 Sam. 27:8; Is. 51:9; 63:9); to the time just before the flood (Gen. 6:4)." [4] Many Scriptures do favour the use of the Name. The biblical law does not prohibit the use of the Name, but it warns against “misuse”, “blaspheming” or in ordinary terms, “taking lightly” the Name of YHWH. The Biblical texts suggest the people of the Bible - including the patriarchs - used the Name of YHWH. A wealth of scriptures support this notion.[5][unreliable source?]

Evidence

theophoric names

Yahū" or "Yehū" is a common short form for "Yahweh" in Hebrew theophoric names; as a prefix it sometimes appears as "Yehō-". This has caused two opinions:

- In former times (at least from c.1650 AD), that it was abbreviated from the supposed pronunciation "Yehowah", rather than "Yahweh" which contains no 'o'- or 'u'-type vowel sound in the middle.

- [6] Recently, that, as "Yahweh" is likely an imperfective verb form, "Yahu" is its corresponding preterite or jussive short form: compare yiŝtahaweh (imperfective), yiŝtáhû (preterit or jussive short form) = "do obeisance".

Those who argue for (1) are the: George Wesley Buchanan in Biblical Archaeology Review; Smith’s 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible; Section # 2.1 The Analytical Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon (1848)[6] in its article הוה

Smith’s 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible says that "Yahweh" is possible because shortening to "Yahw" would end up as "Yahu" or similar.The Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906 in the Article:Names Of God has a very similar discussion, and also gives the form Jo or Yo (יוֹ) contracted from Jeho or Yeho (יְהוֹ). The Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1910-11, vol. 15, pp. 312, in its article "JEHOVAH", also says that "Jeho-" or "Jo" can be explained from "Yahweh", and that the suffix "-jah" can be explained from "Yahweh" better than from "Yehowah".

Chapter 1 of The Tetragrammaton and the Christian Greek Scriptures, under the heading: The Pronunciation Of Gods Name quotes from Insight on the Scriptures, Volume 2, page 7: Hebrew Scholars generally favor "Yahweh" as the most likely pronunciation. They point out that the abbreviated form of the name is Yah (Jah in the Latinized form), as at Psalm 89:8 and in the expression Hallelu-Yah (meaning "Praise Yah, you people!") (Ps 104:35; 150:1,6). Also, the forms Yehoh', Yoh, Yah, and Ya'hu, found in the Hebrew spelling of the names of Jehoshaphat, Joshaphat, Shephatiah, and others, can all be derived from Yahweh.

Using consonants as semi-vowels (v/w)

In ancient Hebrew, the letter ו, known to modern Hebrew speakers as vav, was a semivowel /w/ (as in English, not as in German) rather than a /v/.[7] The letter is referred to as waw in the academic world. Because the ancient pronunciation differs from the modern pronunciation, it is common today to represent יהוה as YHWH rather than YHVH.

In Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written and the rest are written only ambiguously, as the vowel letters double as consonants (similar to the Latin use of V to indicate both U and V). See Matres lectionis for details. For similar reasons, an appearance of the Tetragrammaton in ancient Egyptian records of the 13th century BC sheds no light on the original pronunciation.[8] Therefore it is, in general, difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced from its spelling only, and the Tetragrammaton is a particular example: two of its letters can serve as vowels, and two are vocalic place-holders, which are not pronounced.

This difficulty occurs somewhat also in Greek when transcribing Hebrew words, because of Greek's lack of a letter for consonant 'y' and (since loss of the digamma) of a letter for "w", forcing the Hebrew consonants yod and waw to be transcribed into Greek as vowels. Also, non-initial 'h' caused difficulty for Greeks and was liable to be omitted; х (chi) was pronounced as 'k' + 'h' (as in modern Hindi "lakh") and could not be used to spell 'h' as in e.g. Modern Greek Χάρρι = "Harry".

Y or J?

The English practice of transliterating the Biblical Hebrew Yodh as "j" and pronouncing it "dzh" (/dʒ/) started when, in late Latin, the pronunciation of consonantal "i" changed from "y" (as in English "yet") to "dzh" but continued to be spelled "i", bringing along with it Latin transcriptions and spoken renderings of Biblical and other foreign words and names.

A direct rendering of the Hebrew yod would be "y" in English. However, most transliterations of the biblical Hebrew texts represent the Hebrew 'yod' by using the English letter 'J'. This letter, and the accompanying 'J' sound/pronunciation is clearly evident in anglicized versions of Hebrew proper nouns, i.e. names such as Jesus*, Jeremiah, Joshua**, Judah, Job, Jerusalem, Jehoshaphat, and Jehovah. Although it can be argued that the 'Y' form is more correct i.e. more like the Jewish/Hebrew pronunciations, in the English-speaking world, this 'J' form for such Bible names is now the norm and has been so for centuries.

The letters "J" and "V" as distinct from "I" and "U" relates back to 1565 when a Parisian printer (Gille Beyes) changed 'J' and ‘V’ from indistinct vowels into consonants. In the Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, we find that the J sound as we now know it has only been in the English language since the 1700s, prior to this, the J was a capital I. Some centre column references in the Bible affirm this.[citation needed]

Kethib and Qere and Qere perpetuum

The original consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible was provided with vowel marks by the Masoretes to assist reading. In places where the consonants of the text to be read (the Qere) differed from the consonants of the written text (the Kethib), they wrote the Qere in the margin as a note showing what was to be read. In such a case the vowels of the Qere were written on the Kethib. For a few very frequent words the marginal note was omitted: this is called Q're perpetuum.

One of these frequent cases was God's name, that should not be pronounced, but read as "Adonai" ("My Lord [plural of majesty]"), or, if the previous or next word already was "Adonai", or "Adoni" ("My Lord"), as "Elohim" ("God"). This combination produces יְהֹוָה and יֱהֹוִה respectively, non-words that would spell "yehovah" and "yehovih" respectively.

The oldest manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, such as the Aleppo Codex and the Codex Leningradensis mostly write יְהוָה (yehvah), with no pointing on the first H; this points to its Qere being 'Shema', which is Aramaic for "the Name".

Gérard Gertoux wrote that in the Leningrad Codex of 1008-1010, the Masoretes used 7 different vowel pointings [i.e. 7 different Q're's] for YHWH.[9]

Frequency of use in scripture

According to the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon, יְהֹוָה (Qr אֲדֹנָי) occurs 6518 times, and יֱהֹוִה (Qr אֱלֹהִים) occurs 305 times in the Masoretic Text. Since the scribes admit removing it at least 134 different times and inserting Adonai, we may conclude that the four letter Name יהוה appeared about 7,000 times.

It appears 6,823 times in the Jewish Bible, according to the Jewish Encyclopedia, and 6,828 times each in the Biblia Hebraica and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia texts of the Hebrew Scriptures.

The vocalizations of יְהֹוָה and אֲדֹנָי are not identical

The schwa in YHWH (the vowel under the first letter, ְ) and the hataf patakh in 'DNY (the vowel under its first letter, ֲ), appear different. One reason suggested[who?] is that the spelling יֲהֹוָה (with the hataf patakh) risks that a reader might start pronouncing "Yah", which is a form of the Name, thus completing the first half of the full Name[citation needed]. Alternatively, the vocalization can be attributed to Biblical Hebrew phonology[10], where the hataf patakh is grammatically identical to a schwa, always replacing every schwa naḥ under a guttural letter. Since the first letter of אֲדֹנָי is a guttural letter, while the first letter of יְהֹוָה is not, the hataf patakh under the (guttural) aleph reverts to a regular schwa under the (non-guttural) yodh.

Very old scrolls

The discovery of the Qumran scrolls has added support to some parts of this position[clarification needed]. These scrolls are unvocalized, showing that the position of those who claim that the vowel marks were already written by the original authors of the text is untenable. Many of these scrolls write (only) the tetragrammaton in paleo-Hebrew script, showing that the Name was treated specially. See this link.

The text in the Codex Leningrad B 19A, 1008 A.D, shows יהוה with various different vowel points, indicating that the name was to be read as Yehwah', Yehwih, and a number of times as Yehowah, as in Genesis 3:15. The Aleppo and Leningrad codices do not use the holem (o) in their vocalization, but it is used in a few instances, so that the (systematic) spelling "Yehovah" is more recent than about 1000 A.D. or from a different tradition. Nevertheless, this spelling does appear in both codices.

Josephus's description of vowels

Josephus in Jewish Wars, chapter V, verse 235, wrote "τὰ ἱερὰ γράμματα· ταῦτα δ' ἐστὶ φωνήεντα τέσσαρα" ("...[engraved with] the holy letters; and they are four vowels"), presumably because Hebrew yod and waw, even if consonantal, would have to be transcribed into the Greek of the time as vowels.

Conclusions

Various people draw various conclusions from this Greek material.

William Smith writes in his 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible" about the different Hebrew forms supported by these Greek forms:

- ... The votes of others are divided between יַהְוֶה (yahveh) or יַהֲוֶה (yahaveh), supposed to be represented by the Ιαβέ of Epiphanius mentioned above, and יַהְוָה (yahvah) or יַהֲוָה (yahavah), which Fürst holds to be the Ιευώ of Porphyry, or the Ιαού of Clemens Alexandrinus.

Early Greek and Latin forms

The writings of the Church Fathers contain several references to God's name in Greek or Latin. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1907)] and B.D. Eerdmans: [11]

- Diodorus Siculus[12] writes Ἰαῶ (Iao);

- Irenaeus reports[13] that the Gnostics formed a compound Ἰαωθ (Iaoth) with the last syllable of Sabaoth. He also reports[14] that the Valentinian heretics use Ἰαῶ (Iao);

- Clement of Alexandria[15] writes Ἰαοὺ (Iaou) - see also below;

- Origen of Alexandria,[16] Iao;

- Porphyry,[17] Ἰευώ (Ieuo);

- Epiphanius (d. 404), who was born in Palestine and spent a considerable part of his life there, gives[18] Ia and Iabe (one codex Iaue);

- Pseudo-Jerome,[19] tetragrammaton legi potest Iaho;

- Theodoret (d. c. 457) writes Ἰάω (Iao); he also reports[20] that the Samaritans say Ἰαβέ (Iabe), Ἰαβαι (Iabai), while the Jews say Ἀϊά (Aia).[21] (The latter is probably not יהוה but אהיה Ehyeh = "I am" (Exod. iii. 14), which the Jews counted among the names of God.)

- James of Edessa (cf.[22]), Jehjeh;

- Jerome[23] speaks of certain ignorant Greek writers who transcribed the Hebrew Divine name יהוה as ΠΙΠΙ.

Clement's Stromata

Clement of Alexandria writes in Stromata V, 6:34-35

- "Πάλιν τὸ παραπέτασμα τῆς εἰς τὰ ἅγια τῶν ἁγίων παρόδου, κίονες τέτταρες αὐτόθι, ἁγίας μήνυμα τετράδος διαθηκῶν παλαιῶν, ἀτὰρ καὶ τὸ τετράγραμμον ὄνομα τὸ μυστικόν, ὃ περιέκειντο οἷς μόνοις τὸ ἄδυτον βάσιμον ἦν· λέγεται δὲ Ἰαουε, ὃ μεθερμηνεύεται ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἐσόμενος. Καὶ μὴν καὶ καθʼ Ἕλληνας θεὸς τὸ ὄνομα τετράδα περιέχει γραμμάτων."

The translation[7] of Clement's Stromata in Volume II of the classic Ante-Nicene Fathers series renders this as:

- "... Further, the mystic name of four letters which was affixed to those alone to whom the adytum was accessible, is called Jave, which is interpreted, 'Who is and shall be.' The name of God, too [i.e. θεὸς], among the Greeks contains four letters."[24]

Of Clement's Stromata there is only one surviving manuscript, the Codex L (Codex Laurentianus V 3), from the 11th century. Other sources are later copies of that ms. and a few dozen quotations from this work by other authors. For Stromata V,6:34, Codex L has ἰαοὺ. The critical edition by Otto Stählin (1905) gives the forms

- "ἰαουέ Didymus Taurinensis de pronunc. divini nominis quatuor literarum (Parmae 1799) p. 32ff, ἰαοὺ L, ἰὰ οὐαὶ Nic., ἰὰ οὐὲ Mon. 9.82 Reg. 1888 Taurin. III 50 (bei Did.), ἰαοῦε Coisl. Seg. 308 Reg. 1825."

and has Ἰαουε in the running text. The Additions and Corrections page gives a reference to an author who rejects the change of ἰαοὺ into Ἰαουε.[25]

Other editors give similar data. A catena (Latin: chain) referred to by A. le Boulluec [26] ("Coisl. 113 fol. 368v") and by Smith’s 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible" ("a catena to the Pentateuch in a MS. at Turin") is reported to have "ια ουε".

Jehovah (and similar)

Later, Christian Europeans who did not know about the Q're perpetuum custom took these spellings at face value, producing the form "Jehovah" and spelling variants of it. The Catholic Encyclopedia [1913, Vol. VIII, p. 329] states: “Jehovah (Yahweh), the proper name of God in the Old Testament." Had they known about the Q're perpetuum, the term "Jehovah" may have never come in to being[27]. For more information, see the page Jehovah. Alternatively, most scholars recognise Jehovah to be “grammatically impossible” Jewish Encyclopedia (Vol VII, p. 8).

Delitzsch prefers "יַהֲוָה" (yahavah) since he considered the shwa quiescens below ה ungrammatical. In his 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible", William Smith prefers the form "יַהֲוֶה" (yahaveh). Many other variations have been proposed.

יַהְוֶה = Yahweh

| This section may be too long. |

In the early 19th century Hebrew scholars were still critiquing "Jehovah" [a.k.a. Iehovah and Iehouah] because they believed that the vowel points of יְהֹוָה were not the actual vowel points of God's name. The Hebrew scholar Wilhelm Gesenius [1786-1842] had suggested that the Hebrew punctuation יַהְוֶה, which is transliterated into English as "Yahweh", might more accurately represent the actual pronunciation of God's name than the Biblical Hebrew punctuation "יְהֹוָה", from which the English name Jehovah has been derived.

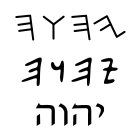

Wilhelm Gesenius is noted for being one of the greatest Hebrew and biblical scholars [8]. His proposal to read YHWH as "יַהְוֶה" (see image to the right) was based in large part on various Greek transcriptions, such as [[iabe|ιαβε]], dating from the first centuries AD, but also on the forms of theophoric names.

- In his Hebrew Dictionary Gesenius (see image of German text) supports the pronunciation "Yahweh" because of the Samaritan pronunciation Ιαβε reported by Theodoret, and that the theophoric name prefixes YHW [Yeho] and YH [Yo] can be explained from the form "Yahweh".

-

- Today many scholars accept Gesenius's proposal to read YHWH as יַהְוֶה.

- (Here 'accept' does not necessarily mean that they actually believe that it describes the truth, but rather that among the many vocalizations that have been proposed, none is clearly superior[neutrality disputed][weasel words][original research?]. That is, 'Yahweh' is the scholarly convention, rather than the scholarly consensus[neutrality disputed][weasel words][original research?].)

In the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1910,in the article Jehovah (Yahweh), under the sub-title:"To take up the ancient writers", the editors wrote:

The judicious reader will perceive that the Samaritan pronunciation Jabe probably approaches the real sound of the Divine name closest; the other early writers transmit only abbreviations or corruptions of the sacred name. Inserting the vowels of Jabe into the original Hebrew consonant text, we obtain the form Jahveh (Yahweh), which has been generally accepted by modern scholars as the true pronunciation of the Divine name. It is not merely closely connected with the pronunciation of the ancient synagogue by means of the Samaritan tradition, but it also allows the legitimate derivation of all the abbreviations of the sacred name in the Old Testament.

In Smith’s 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible", the author displays some of the above forms and concludes:

- But even if these writers were entitled to speak with authority, their evidence only tends to show in how many different ways the four letters of the word יהוה could be represented in Greek characters, and throws no light either upon its real pronunciation or its punctuation.

On the other hand however, is the common belief that the true name was never lost, the Encyclopedia Judaica concludes:

"The true pronunciation of the name YHWH was never lost. Several early Greek writers of the Christian church testify that the name was pronounced Yahweh."

The editors of New Bible Dictionary (1962 write:

- The pronunciation Yahweh is indicated by transliterations of the name into Greek in early Christian literature, in the form Ιαουε (Clement of Alexandria) or Ιαβε (Theodoret; by this time β had the pronunciation of v).

The main approaches in modern attempts to determine a pronunciation of יהוה have been study of the Hebrew Bible text, study of theophoric names and study of early Christian Greek texts that contain reports about the pronunciation. Evidence from Semitic philology and archeology has been tried, resulting in a "scholarly convention to pronounce יהוה as Yahweh".

Gesenius' proposal gradually became accepted as the best scholarly reconstructed vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton.

Preferences of various modern groups

Religious groups

| This section contains information which may be of unclear or questionable importance or relevance to the article's subject matter. Please help improve this article by clarifying or removing superfluous information. |

Randy Weaver, of the Aryan Nations church, used the word Yahweh to describe God.

Bible Translations

| This section contains information which may be of unclear or questionable importance or relevance to the article's subject matter. Please help improve this article by clarifying or removing superfluous information. |

| Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (March 2009) |

| This article is in a list format that may be better presented using prose. You can help by converting this section to prose, if appropriate. Editing help is available. (March 2009) |

The New Jerusalem Bible (1966) uses "Yahweh" exclusively.

The Bible In Basic English (1949/1964) uses "Yahweh" eight times, including Exodus 6.2.

The Amplified Bible (1954/1987) uses "Yahweh" in Exodus 6.3.

The Holman Christian Standard Bible (1999/2002) uses "Yahweh" over 50 times,including Exodus 6.2.

The World English Bible (WEB) [a Public Domain work with no copyright] uses "Yahweh" some 6837 times.

The New Living Translation (1996/2004) uses "Yahweh" eight times, including Exodus 6.2.

The Rotherham Emphasized Bible retains "Yahweh" throughout the Old Testament.

The Anchor Bible retains "Yahweh" throughout the Old Testament.

The King James Version uses "Jehovah".

The American Standard Version uses "Jehovah".

Bible translators James Mofatt and Dr J. M. Power Smith declare the Tetragrammaton should have been transliterated “Yahweh”.

Modern academic books and papers

| This section contains information which may be of unclear or questionable importance or relevance to the article's subject matter. Please help improve this article by clarifying or removing superfluous information. |

| Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (March 2009) |

There are many witnesses who believe the correct name should be Yahweh; both Jewish and Christian authorities, such as the Jewish Encyclopedia. Bible Encyclopedias, lexicons, and grammars, declare the Tetragrammaton should have been transliterated “Yahweh”. Other sources include the Seventh Day Adventist Commentary Vol. 1, p511, under Exodus 3:15; Herbert Armstrong, the New Morality, pp. 128 – 129; David Neufeld, Review and Herald, December 15, 1971, page11; A New Translation of the Bible, pp 20 – 21 (Harper and Row © 1954) and J.D Douglas; New Bible Dictionary, (Wm B Eerdman’s Pub Co. © (1962), p9 as concluded: “Strictly speaking Yahweh is the only ‘Name’ of God”.

Some modern writers[specify], particularly in mythology and anthropology, use 'Yahweh' specifically, rather than 'God', to describe the Biblical God as a way of trying to display Christian and Jewish concepts as being on an even plane with concepts and deities from other religions[weasel words]. This does not necessarily represent a majority view, but the practice has grown in recent years.

Criticisms and theories of origin and meaning

Yahweh (ie. YHWH) is believed by scholars to derive from hawah[28], a Hebrew root cognate to an Arabic word meaning fall (down), and which is usually translated with this sense where it occurs in the Book of Job[29]; scholars therefore usually proffer interpretations of Yahweh along the lines of he [who] falls, he [who causes to] fall, or more figuratively he [who] casts down. Among other possibilities, it would be a suitable name for a storm deity, perhaps representing the fall of rain, the casting down of lightning, etc[30]

Biblical passages attributed by textual scholars to the priestly source expressly declare that the name Yahweh (YHWH) was unknown to the biblical patriarchs[31], and the episode of the burning bush in the Elohist text suggests that Moses and the Israelites had not known the deity under that name before, if they had previously worshipped him at all[citation needed]. The divergent Yahwist account, which suggests that Yahweh had always been worshipped, is thought to be due to the Kenite element in the Kingdom of Judah.

The Elohist account describes Jethro, a Midianite priest, meeting the Israelites near Mount Sinai, and extolling the virtues of Yahweh to them; scholars surmise therefore that Israelite use of the name Yahweh originates among the people in whose lands the mountain lay - the Midianites according to the biblical text. The region around Mount Seir, which is one of two main modern candidates for the location of Sinai, have several cult places sacred to the storm and weather god(s); at Serabit el Khadim, within this region, petroglyphs have been found which seem to confirm that Yahweh was at one time reverenced by the tribes in the area.

According to a theory, Yahweh may be a compound from Yahu or Yah, explaining why there are many theophoric names (of people and places) based on Yah but few based on Yahweh as a whole; the theory proposes that Yahu/Yah is the name of a deity worshipped throughout the Western Semitic area. Based on damaged writing at Elba, dated to the reign of Ebrum, it has been proposed by Mark Smith[32] that Yah was the original name of Yam, and that this Yah must be another form of Ea, the Babylonian version of Enki, with which Yam has several similarities. Jean Bottero and other archaeologists have consequently supported the view that Yahweh derives from this Yah, and ultimately from Enki[33][34]. It has also not gone unnoticed that the Egyptian word for moon was Yah, and the semitic moon god was Sin, after which scholars believe Sinai and the surrounding wilderness of Sin were named.

Usage of the name YHWH

| It has been suggested that this article or section be merged into Tetragrammaton. (Discuss) |

In ancient Judaism

Several centuries before the Christian era the name of their god YHWH had ceased to be commonly used by the Jews. Some of the later writers in the Old Testament employ the appellative Elohim, God, prevailingly or exclusively.

The oldest complete Septuagint (Greek Old Testament) versions, from around the second century A.D., consistently use Κυριος (= "Lord"), where the Hebrew has YHWH, corresponding to substituting Adonay for YHWH in reading the original; in books written in Greek in this period (e.g. Wisdom, 2 and 3 Maccabees), as in the New Testament, Κυριος takes the place of the name of God. However, older fragments contain the name YHWH.[35] In the P. Ryl. 458 (perhaps the oldest extant Septuagint manuscript) there are blank spaces, leading some scholars to believe that the Tetragrammaton must have been written where these breaks or blank spaces are.[36]

Josephus, who as a priest knew the pronunciation of the name, declares that religion forbids him to divulge it.

Philo calls it ineffable, and says that it is lawful for those only whose ears and tongues are purified by wisdom to hear and utter it in a holy place (that is, for priests in the Temple). In another passage, commenting on Lev. xxiv. 15 seq.: "If any one, I do not say should blaspheme against the Lord of men and gods, but should even dare to utter his name unseasonably, let him expect the penalty of death." [37]

Various motives may have concurred to bring about the suppression of the name:

- An instinctive feeling that a proper name for God implicitly recognizes the existence of other gods may have had some influence; reverence and the fear lest the holy name should be profaned among the heathen.

- Desire to prevent abuse of the name in magic. If so, the secrecy had the opposite effect; the name of the God of the Jews was one of the great names, in magic, heathen as well as Jewish, and miraculous efficacy was attributed to the mere utterance of it.

- Avoiding risk of the Name being used as an angry expletive, as reported in Leviticus 24:11 in the Bible.

In the liturgy of the Temple the name was pronounced in the priestly benediction (Num. vi. 27) after the regular daily sacrifice (in the synagogues a substitute— probably Adonai— was employed);[38] on the Day of Atonement the High Priest uttered the name ten times in his prayers and benediction.

In the last generations before the fall of Jerusalem, however, it was pronounced in a low tone so that the sounds were lost in the chant of the priests.[39]

Theophoric uses

"Yahū" or "Yehū" is a common short form for "Yahweh" in Hebrew theophoric names (a type of name including those which became western names like 'Jonathan', 'Joachin', and 'John')); as a prefix it sometimes appears as "Yehō-". In former times that was thought to be abbreviated from the supposed pronunciation "Yehowah". There is nowadays an opinion [9] that, as "Yahweh" is likely an imperfective verb form, "Yahu" is its corresponding preterite or jussive short form: compare yiŝtahaweh (imperfective), yiŝtáhû (preterit or jussive short form) = "do obeisance".

In some places, such Exodus 15:2, the name YHWH is shortened to יָהּ (Yah). This same syllable is found in Hallelu-yah. Here the ה has mappiq, i.e., is consonantal, not a mater lectionis.

It is often assumed that this is also the second element -ya of the Aramaic "Marya": the Peshitta Old Testament translates Adonai with "Mar" (Lord), and YHWH with "Marya".

In later Judaism

After the destruction of the Temple (70 C.E) the liturgical use of the name ceased, but the tradition was perpetuated in the schools of the rabbis.[40] It was certainly known in Babylonia in the latter part of the 4th century,[41] and not improbably much later. Nor was the knowledge confined to these pious circles; the name continued to be employed by healers, exorcists and magicians, and has been preserved in many places in magical papyri.

The vehemence with which the utterance of the name is denounced in the Mishna—He who pronounces the Name with its own letters has no part in the world to come![42] —suggests that this misuse of the name was not uncommon among Jews[citation needed]. Modern observant Jews no longer voice the name יהוה aloud. It is believed to be too sacred to be uttered and is often referred to as the 'Ineffable', 'Unutterable' or 'Distinctive Name'.[43][44].

In Modern Judaism

The new Jewish Publication Society Tanakh 1985 follows the traditional convention of translating the Divine Name as "the LORD" (in all caps). The Artscroll Tanakh translates the Divine Name as "HaShem" (literally, "The Name").

When the Divine Name is read during prayer, "Adonai" ("My Lord") is substituted. However, when practicing a prayer or referring to one, Orthodox Jews will say "AdoShem" instead of "Adonai". When speaking to another person "HaShem" is used.

Liturgical usage of 'Yahweh'

Among the Samaritans

The Samaritans, who otherwise shared the scruples of the Jews about the utterance of the name, seem to have used it in judicial oaths to the scandal of the rabbis.[45] (Their priests have preserved a liturgical pronunciation "Yahwe" or "Yahwa" to the present day.) [46] However, the Aramaic "Shema" (שמא) remains the everyday (including liturgical) usage of the name, akin to Hebrew "Hashem" (השם).

Roman Catholic Church

The first edition of the official Vatican Nova Vulgata Bibliorum Sacrorum, published at 1979, used the form Iahveh for rendering the Tetragrammaton.[47] Later editions of this version replaced "Iahveh" with "Dominus".

On August 8, 2008, Bishop Arthur J. Serratelli of Paterson, N.J., chairman of the U.S. bishop's Committee on Divine Worship, announced a new Vatican directive regarding the use of the name of God in the sacred liturgy. "Specifically, the word 'Yahweh' may no longer be 'used or pronounced' in songs and prayers during liturgical celebrations."

Scriptural loss and retention of the name

Loss of the Tetragrammaton in the Septuagint

| It has been suggested that this article or section be merged into Tetragrammaton. (Discuss) |

| This article contains weasel words, vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. Such statements should be clarified or removed. (March 2009) |

Septuagint study does give some credence to the possibility that the Divine Name appeared in its original texts. Dr Sidney Jellicoe concluded that "Kahle is right in holding that LXX [= Septuagint] texts, written by Jews for Jews, retained the Divine Name in Hebrew Letters (palaeo-Hebrew or Aramaic) or in the Greek-letters imitative form ΠΙΠΙ, and that its replacement by Κύριος was a Christian innovation."[48] Jellicoe draws together evidence from a great many scholars (B. J. Roberts, Baudissin, Kahle and C.H Roberts) and various segments of the Septuagint to draw the conclusions that: a) the absence of “Adonai” from the text suggests that the insertion of the term “Kurious” was a later practice, b) in the Septuagint “Kurios”, or in English “Lord”, is used to substitute the Name YHWH, and c) the Tetragrammaton appeared in the original text, but Christian copyists removed it. There is therefore a strong possibility that the Sacred Name was once integrated within the Greek text, but eventually disappeared.

Meyer suggests as one possibility that “as modern Hebrew letters were introduced, the next step was to follow modern Jews and insert “Kurios”, Lord. This would prove this innovation was of a late date.”

Bible scholars and translators as Eusebius and Jerome (translator of the Latin Vulgate) used the Hexapla. Both attest to the importance of the sacred Name and that the most reliable manuscripts contained the Tetragrammaton in Hebrew letters.[citation needed]

Dr F. F. Bruce in the The Books and the Parchments [49] illustrates that the religious language of the Greeks is in effect, pagan. Bruce demonstrates that the words commonly used today in Christianity are pagan Greek words and substitutes; this includes words such as “Christ”,”Lord”, and “God” (The English “Jesus” is not the same as “Iesous” in Greek). For this reason, a few groups such as the Assemblies of Yahweh and the Jehovah's Witnesses have maintained that they are restoring the purity of worship - by using the sacred Names and Hebrew titles. On the other hand, Christianity still generally regards the sacred Name as a minor issue while observant Jews believe it is respectful not to speak the Name at all [50].

Later translations into European languages which descended from the Septuagint tended to follow the Greek and use each language's word for "lord": Latin "Dominus", German "der Herr", Polish "Pań", English "the Lord", French "le Seigneur", etc.

In the New Testament

| It has been suggested that this article or section be merged into Tetragrammaton. (Discuss) |

Since the Tetragrammaton does not appear in the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, virtually all translations refrain from inserting it into the English. The vast majority of New Testament translations therefore render the Greek kyrios as "lord" and theos as "God". Nevertheless, the Sacred Scriptures Bethel Edition inserts the name Yahweh in the New Testament, while the New World Translation inserts the name Jehovah in the New Testament.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Tetragrammaton |

- Adon

- Allah

- Ea

- El (god)

- Ellil

- Elohim

- God in the Bahá'í Faith, God in Christianity, God in Islam, God in Judaism

- Jehovah

- I am that I am

- -ihah

- INRI

- Jah

- List of Septuagint versions that have the Tetragrammaton

- List of Hebrew versions of the New Testament that have the Tetragrammaton

- Names of God in Judaism

- Tetragrammaton (YHWH)

- Tetragrammaton in the New Testament

- Theophoric names

- Yam (god) (Ya'a, Yaw)

"Tetragrammaton" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

"Tetragrammaton" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica. "Jehovah_(Yahweh)" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.

"Jehovah_(Yahweh)" in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.- Criticisms and theories on Yahweh

References

- ^ Encycl. Britannica, 15th edition, 1994, passim.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Changing God's Eternal Law [3]

- ^ [4].

- ^ ;The Analytical Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon by Benjamin Davidson ISBN 0913573035

- ^ (see any Hebrew grammar)

- ^ See pages 128 and 236 of the book "Who Were the Early Israelites?" by archeologist William G. Dever, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003.

- ^ refer to the table on page 144 of Gérard Gertoux's book The Name of God Y.EH.OW.Ah which is pronounced as it is written I_EH_OU_AH.

- ^ Lambdin, Thomas O.: Introduction to Biblical Hebrew, London: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1971

- ^ B.D. Eerdmans, The Name Jahu, O.T.S. V (1948) 1-29

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Histor. I, 94

- ^ Irenaeus, "Against Heresies", II, xxxv, 3, in P. G., VII, col. 840

- ^ Irenaeus, "Against Heresies", I, iv, 1, in P.G., VII, col. 481

- ^ Clement, "Stromata", V, 6, in P.G., IX, col. 60

- ^ Origen, "In Joh.", II, 1, in P.G., XIV, col. 105

- ^ according to Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica I, ix, in P.G., XXI, col. 72

- ^ Epiphanius, Panarion, I, iii, 40, in P.G., XLI, col. 685

- ^ "Breviarium in Psalmos", in P.L., XXVI, 828

- ^ Theodoret, "Ex. quaest.", xv, in P. G., LXXX, col. 244 and "Haeret. Fab.", V, iii, in P. G., LXXXIII, col. 460.

- ^ Footnote #8 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Aïα occurs also in the great magical papyrus of Paris, 1. 3020 (Wessely, Denkschrift. Wien. Akad., Phil. Hist. Kl., XXXVI. p. 120) and in the Leiden Papyrus, Xvii. 31."

- ^ Lamy, "La science catholique", 1891, p. 196

- ^ Jerome, "Ep. xxv ad Marcell.", in P. L., XXII, col. 429

- ^ The Rev. Alexander Roberts, D.D, and James Donaldson, LL.D., ed. "VI. — The Mystic Meaning of the Tabernacle and Its Furniture". The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. II: Fathers of the Second Century (American reprint of the Edinburgh edition ed.). pp. 452. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf02.vi.iv.v.vi.html. Retrieved on 2006-12-19.

- ^ Zu der in L übergelieferten Form ἰαου, vgl. Ganschinietz RE IX Sp. 700, 28ff, der die Änderung in ἰαουε ablehnt.

- ^ Clément d'Alexandrie. Stromate V. Tome I: Introduction, texte critique et index, par A. Le Boulluec, Traduction de † P. Voulet, s. j.; Tome II : Commentaire, bibliographie et index, par A. Le Boulluec, Sources Chrétiennes n° 278 et 279, Editions du Cerf, Paris 1981. (Tome I, pp. 80,81)

- ^ ”Job – Introduction, Anchor Bible, volume 15, page XIV and “Jehovah” Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition, volume 15

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannia, 1911

- ^ Job 37:6

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannia, 1911

- ^ Exodus 6:3

- ^ Smith, Mark S. (2001) "The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel's Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts" (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- ^ Bottero, Jean (2004) "Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia" (University Of Chicago Press) ISBN 0-226-06718-1

- ^ Cohn, Norman. Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come, The Ancient Roots of Apocalyptic Faith. New Haven and London. Yale University Press, 1993.

- ^ The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology Volume 2, page 512

- ^ Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza (Oxford:Basil Blackwell,1959) p. 222

- ^ Footnote #3 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Josephus, Ant. ii. 12, 4; Philo, Vita Mosis, iii. II (ii. 114, ed. Cohn and Wendland); ib. iii. 27 (ii. 206). The Palestinian authorities more correctly interpreted Lev. xxiv. 15 seq., not of the mere utterance of the name, but of the use of the name of God in blaspheming God."

- ^ Footnote #4 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Siphre, Num. f 39, 43; M. Sotak, iii. 7; Sotah, 38a. The tradition that the utterance of the name in the daily benedictions ceased with the death of Simeon the Just, two centuries or more before the Christian era, perhaps arose from a misunderstanding of Menahoth, 109b; in any case it cannot stand against the testimony of older and more authoritative texts.

- ^ Footnote #5 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Yoma, 39b; Jer. Yoma, iii. 7; Kiddushin, 71a."

- ^ Footnote #1 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:"R. Johannan (second half of the 3rd century), Kiddushin, 71a."

- ^ Footnote #2 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:"Kiddushin, l.c. = Pesahim, 50a"

- ^ Footnote #3 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "M. Sanhedrin, x.I; Abba Saul, end of 2nd century."

- ^ Judaism 101 on the Name of God

- ^ For example, see Insights of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik by Saul Weiss and Joseph Dov Soloveitchik, p.9. and Jewish Identity and Society in the Seventeenth Century by Minna Rozen, p.67.[5]

- ^ Footnote #4 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:Jer. Sanhedrin, x.I; R. Mana, 4th century.

- ^ Footnote #11 from page 312 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica reads: "See Montgomery, Journal of Biblical Literature, xxv. (1906), 49-51."

- ^ "Dixítque íterum Deus ad Móysen: «Hæc dices fíliis Israel: Iahveh (Qui est), Deus patrum vestrórum, Deus Abraham, Deus Isaac et Deus Iacob misit me ad vos; hoc nomen mihi est in ætérnum, et hoc memoriále meum in generatiónem et generatiónem." (Exodus 3:15)

- ^ Sidney Jellicoe, Septuagint and Modern Study (Eisenbrauns, 1989, ISBN 0931464005) pp. 271, 272.

- ^ Dr F. F. Bruce, The Books and the Parchments, (p. 159).

- ^ Judaism 101 http://www.jewfaq.org/name.htm

This article incorporates text from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Yahweh |

- Bibliography on the Tetragrammaton in the Dead Sea Scrolls

- Encyclopedia Mythica. 2004. Arbel, Ilil. "Yahweh."

- Metatron as the Tetragrammaton

- Hebrew Names of G-d (including YHVH), with audio

- Easton's Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.) 1887. "Jehovah."

- [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=52&letter=N Jewish Encyclopedia count of number of times the Tetragrammaton is used

- The Sacred Name: Yahveh or Yahweh?

- YHWH/YHVH -- Tetragrammaton

- The Sacred Name Yahweh, a publication by Qadesh La Yahweh Press