Invalid proof

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2008) |

In mathematics, there are a variety of spurious proofs of obvious contradictions. Although the proofs are flawed, the errors, usually by design, are comparatively subtle. These fallacies are normally regarded as mere curiosities, but can be used to show the importance of rigor in mathematics. Pseudaria, an ancient book of false proofs, is attributed to Euclid.

This page is an evaluative and critical listing of some of the more common invalid proofs.

Contents |

[edit] Power and root

[edit] Proof that 1 = −1

[edit] Version 1

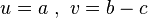

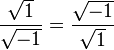

Start with the identity

Convert both sides of the equation into the vulgar fractions

Apply square roots on both sides to yield

Multiply both sides by  to obtain

to obtain

Any number's square root squared gives the original number, so

The proof is invalid because it applies the following principle for square roots incorrectly:

This is only true when x and y are positive real numbers, which is not the case in the proof above. Thus, the proof is invalid.

[edit] Version 2

By incorrectly manipulating radicals, the following invalid proof is derived:

Q.E.D.

The rule  is generally valid only if at least one of the two numbers x or y is positive, which is not the case here. Alternatively, one can view the square root as a 2-valued function over the complex numbers; in this case both sides of the above equation evaluate to {1, -1}.

is generally valid only if at least one of the two numbers x or y is positive, which is not the case here. Alternatively, one can view the square root as a 2-valued function over the complex numbers; in this case both sides of the above equation evaluate to {1, -1}.

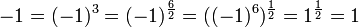

[edit] Version 3

By crossing into and out of the realm of complex numbers, the following invalid proof is derived:

Q.E.D.

The equation abc = (ab)c, when b and/or c are fractions, is generally valid only when a is positive, which is not the case here, leading to an invalid proof.

Additionally, the last step takes the square root of 1, which, depending on the situation, can be either 1 or -1

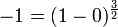

[edit] Version 4

Start with the Pythagorean identity

Raise both sides of the equation to the 3/2 power to obtain

Let x = π

Q.E.D.

In this proof, the fallacy is in the third step, where the rule (ab)c = abc is applied without ensuring that a is positive. Also, in the 4th step, not all possible roots are explored for  . Although 1 is an answer, it is not the only answer, as -1 would also work. Throwing out the erroneous 1 answer leaves a correct -1=-1.

. Although 1 is an answer, it is not the only answer, as -1 would also work. Throwing out the erroneous 1 answer leaves a correct -1=-1.

[edit] Version 5

Square both sides

Square-root both sides

Multiply i to both sides

- 1 = − 1

Q.E.D.

The error is in the fourth to fifth step, where it misuses the same square root principle used in Version 1.

is invalid because the denominator (-1) on the LHS is not a positive real number.

[edit] Proof that x=y for any real x, y

If ab = ac then b = c. Therefore, since 1x = 1y, we may deduce x = y.

Q.E.D.

The error in this proof lies in the fact that the stated rule is true only for positive  .

.

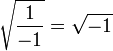

[edit] Proof that the square root of -1 = 1

Q.E.D.

The error in this proof lies in the last line, where we are ignoring the other three "fourth roots" of 1, which are -1, i and -i. Seeing as we have squared our figure and then taken roots, we can't always assume that all the roots will be correct. So the correct "fourth roots" are i and -i, which are the imaginary numbers defined to be  . This idea is shown in this next invalid proof:

. This idea is shown in this next invalid proof:

[edit] Proof that -2 = 2

Q.E.D.

Again, the error is that we have introduced another square root by squaring, then taking roots. The only correct square root of 4 here is -2.

This is the common fallacy of thinking , but that is only true if

, but that is only true if  . For real numbers, we can only say

. For real numbers, we can only say  , the absolute value of x. So, using the correct rule gives the valid

, the absolute value of x. So, using the correct rule gives the valid

This is no longer a contradiction since | − 2 | = 2.

[edit] Division by zero

[edit] Proof that 2 = 1

1. Let a and b be equal non-zero quantities

2. Multiply through by a

3. Subtract

4. Factor both sides

5. Divide out

6. Observing that

7. Combine like terms on the left

8. Divide by the non-zero b

Q.E.D.[1]

The fallacy is in line 5: the progression from line 4 to line 5 involves division by (a − b), which is zero since a equals b. Since division by zero is undefined, the argument is invalid. Deriving that the only possible solution for lines 5, 6, and 7, namely that a = b = 0, this flaw is evident again in line 7, where one must divide by b (0) in order to produce the fallacy (not to mention that the only possible solution denies the original premise that a and b are nonzero). A similar invalid proof would be to say that 2(0) = 1(0) (which is true) therefore, by dividing by zero, 2 = 1. This invalid proof was suggested by Srinivasa Ramanujan[citation needed].

[edit] Proof that all numbers are equal to 1

Suppose we have the following system of linear equations:

Dividing the first equation by c1, we get  Let us now try to solve the system via Cramer's rule:

Let us now try to solve the system via Cramer's rule:

Since each column of the coefficient matrix is equal to the resultant column vector, we have

for all i. Substituting this back into  , we get

, we get

.

.

Q.E.D.

This proof is fallacious because Cramer's rule can only be applied to systems with a unique solution; however, all the equations in the system are obviously equivalent, and insufficient to provide a unique solution. The fallacy occurs when we try to divide | Ai | by | A | , as both are equal to 0.

[edit] Proof that all numbers are equal

Multiplying any number by 0 gives an answer of zero. For example

Rearranging the equation gives

However, by the same reasoning

and since

substitution gives

The same method can be used to show that any number is equal to any other number, and hence all numbers are equal.

Q.E.D.

The fallacy is in the incorrect assumption that division by 0 gives a well-defined value.

[edit] Calculus

[edit] Proof that 2 = 1

By the common intuitive meaning of multiplication we can see that

It can also be seen that for a non-zero x

Now we multiply through by x

Then we take the derivative with respect to x

Now we see that the right hand side is x which gives us

Finally, dividing by our non-zero x we have

Q.E.D.

This proof is false because the differentiation is ignoring the 'x' in the subscript (off  ). As you are differentiation with respect to x, it clearly cannot be held constant. Once this x is accounted for in the differentiation, using the Liebniz rule, the correct answer is obtained:

). As you are differentiation with respect to x, it clearly cannot be held constant. Once this x is accounted for in the differentiation, using the Liebniz rule, the correct answer is obtained:

We take the derivative with respect to x

- 2x = x + x

As expected.

It is often claimed that the original proof is false because both sides of the equation in line 3 represent an integer, and so after differentiating you should get 0 = 0 (as the derivative of a constant function is 0). This is fundamentally incorrect on several levels. Firstly, a function that is only defined on the integers is *not* necessarily a constant function; secondly, the derivative of such a function is *not* 0, it is undefined (picture a graph of the function; it would consist of 'dots'; so have no meaningful slope); and finally, the equation works perfectly well for non-integer values (for example,  ) as evidenced by the fact that, when the differentiation is done correctly, the paradox is eliminated.

) as evidenced by the fact that, when the differentiation is done correctly, the paradox is eliminated.

[edit] Proof that 0 = 1

Begin with the evaluation of the indefinite integral

Through integration by parts, let

and dv = dx

and dv = dx

Thus,

and v = x

and v = x

Hence, by integration by parts

Q.E.D.

The error in this proof lies in an improper use of the integration by parts technique. Upon use of the formula, a constant, C, must be added to the right-hand side of the equation. This is due to the derivation of the integration by parts formula; the derivation involves the integration of an equation and so a constant must be added. In most uses of the integration by parts technique, this initial addition of C is ignored until the end when C is added a second time. However, in this case, the constant must be added immediately because the remaining two integrals cancel each other out.

In other words, the second to last line is correct (1 added to any antiderivative of 1/x is still an antiderivative of 1/x); but the last line is not. You cannot cancel  because they are not necessarily equal. There are infinitely many antiderivatives of a function, all differing by a constant. In this case, the antiderivatives on both sides differ by 1.

because they are not necessarily equal. There are infinitely many antiderivatives of a function, all differing by a constant. In this case, the antiderivatives on both sides differ by 1.

This problem can be avoided if we use definite integrals (i.e. use bounds). Then in the second to last line, 1 would be evaluated between some bounds, which would always evaluate to 1 - 1 = 0. The remaining definite integrals on both sides would indeed be equal.

[edit] Proof that 1 = 0

Take the statement

Taking the derivative of each side,

The derivative of x is 1, and the derivative of 1 is 0. Therefore,

Q.E.D.

The error in this proof is it treats x as a variable, and not as a constant as stated with x = 1 in the proof, when taking its derivative. Taking the proper derivative of x yields the correct result, 0 = 0.

[edit] Infinite series

[edit] Proof that 0 = 1

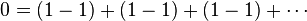

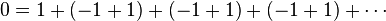

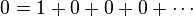

Start with the addition of an infinite succession of zeros

Then recognize that 0 = 1 − 1

Applying the associative law of addition results in

Of course − 1 + 1 = 0

And the addition of an infinite string of zeros can be discarded leaving

Q.E.D.

The error here is that the associative law cannot be applied freely to an infinite sum unless the sum is absolutely convergent (see also conditionally convergent). Here that sum is 1 − 1 + 1 − 1 + · · ·, a classic divergent series. In this particular argument, the second line gives the sequence of partial sums 0, 0, 0, ... (which converges to 0) while the third line gives the sequence of partial sums 1, 1, 1, ... (which converges to 1), so these expressions need not be equal. This can be seen as a counterexample to generalizing Fubini's theorem and Tonelli's theorem to infinite integrals (sums) over measurable functions taking negative values.

In fact the associative law for addition just states something about three-term sums: (a + b) + c = a + (b + c). It can easily be shown to imply that for any finite sequence of terms separated by "+" signs, and any two ways to insert parentheses so as to completely determine which are the operands of each "+", the sums have the same value; the proof is by induction on the number of additions involved. In the given "proof" it is in fact not so easy to see how to start applying the basic associative law, but with some effort one can arrange larger and larger initial parts of the first summation to look like the second. However this would take an infinite number of steps to "reach" the second summation completely. So the real error is that the proof compresses infinitely many steps into one, while a mathematical proof must consist of only finitely many steps. To illustrate this, consider the following "proof" of 1 = 0 that only uses convergent infinite sums, and only the law allowing to interchange two consecutive terms in such a sum, which is definitely valid:

[edit] Proof that the sum of all positive integers is negative

Define the constants S and A by

.

.

Therefore

Adding these two equations gives

Therefore, the sum of all positive integers are negative.

The error in this proof is that it assumes that divergent series obey the ordinary laws of arithmetic.

[edit] Extraneous solutions

[edit] Proof that −2 = 1

Start by attempting to solve the equation

Taking the cube of both sides yields

Replacing the expression within parenthesis by the initial equation and canceling common terms yields

Taking the cube again produces

Which produces the solution x = 2. Substituting this value into the original equation, one obtains

So therefore

Q.E.D.

In the forward direction, the argument merely shows that no x exists satisfying the given equation. If you work backward from x=2, taking the cube root of both sides ignores the possible factors of  which are non-principal cube roots of one. An equation altered by raising both sides to a power is a consequence, but not necessarily equivalent to, the original equation, so it may produce more solutions. This is indeed the case in this example, where the solution x = 2 is arrived at while it is clear that this is not a solution to the original equation. Also, every number has 3 cube roots, 2 complex and one either real or complex. Also the substitution of the first equation into the second to get the third would be begging the question when working backwards.

which are non-principal cube roots of one. An equation altered by raising both sides to a power is a consequence, but not necessarily equivalent to, the original equation, so it may produce more solutions. This is indeed the case in this example, where the solution x = 2 is arrived at while it is clear that this is not a solution to the original equation. Also, every number has 3 cube roots, 2 complex and one either real or complex. Also the substitution of the first equation into the second to get the third would be begging the question when working backwards.

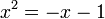

[edit] Proof that 3 = 0

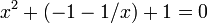

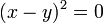

Assume the following equation for a complex x :

Then:

Divide by x (assume x is not 0)

Substituting the last expression for x in the original equation we get:

Substituting x=1 in the original equation yields:

Q.E.D.

The fallacy here is in assuming that x3 = 1 implies x = 1. There are in fact three cubed roots of unity. Two of these roots, which are complex, are the solutions of the original equation. The substitution has introduced the third one, which is real, as an extraneous solution. The equation after the substitution step is implied by the equation before the substitution, but not the other way around, which means that the substitution step could and did introduce new solutions.

[edit] Complex numbers

[edit] Proof that 1 = 3

From Euler's formula we see that

and

so we have

Taking logarithms gives

and hence

Dividing by πi gives

QED.

The mistake is that the rule ln(ex) = x is in general only valid for real x, not for complex x. The complex logarithm is actually multi-valued; and ln( − 1) = (2k + 1)πi for any integer k, so we see that πi and 3πi are two among the infinite possible values for ln(-1).

[edit] Proof that x = y for any real x, y

Let x and y be any two numbers Then let  Let

Let  Let's compute:

Let's compute:

Replacing  , we get:

, we get:

Let's compute  Replacing

Replacing  :

:

So:

Replacing  :

:

Q.E.D.

The mistake here is that from z³ = w³ one may not in general deduce z = w (unless z and w are both real, which they are not in our case).

[edit] Inequalities

[edit] Proof that 1 < 0

Let us first suppose that

Now we will take the logarithm of both sides. As long as x > 0, we can do this because logarithms are monotonically increasing. Observing that the logarithm of 1 is 0, we get

Dividing by ln (x) gives

Q.E.D.

The violation is found in the last step, the division. This step is invalid because ln(x) is negative for 0 < x < 1. While multiplication or division by a positive number preserves the inequality, multiplication or division by a negative number reverses the inequality, resulting in the correct expression 1 > 0.

[edit] Infinity

[edit] Proof that ∞ = 1/4

Since an infinitely large plane has the coordinates of (-∞,∞) × (-∞,∞), this means that

Which can be simplified into

And finally

Now combine the ∞'s:

This itself then simplifies into

And finally, to find the value of ∞ itself,

This can be checked by starting with the equation given in step 1,

Substitute in the above value of ∞ to see if it really works:

Which is then simplified to get

And that then simplifies into

Q.E.D.

This proof's fallacy is using ∞ (infinity) to represent a finite value – in reality infinity is thought of as a direction as opposed to a destination. One of the more unusual aspects of this type of invalid proof is that it can be checked, unlike many other invalid proofs, particularly ones which rely on division by zero. Also, infinity divided by itself is undefined.

[edit] Examples in geometry

[edit] Proof that any angle is zero

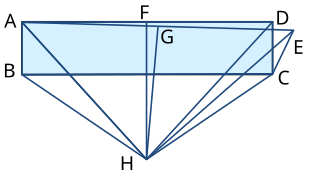

Construct a rectangle ABCD. Now identify a point E such that CD = CE and the angle DCE is a non-zero angle. Take the perpendicular bisector of AD, crossing at F, and the perpendicular bisector of AE, crossing at G. Label where the two perpendicular bisectors intersect as H and join this point to A, B, C, D, and E.

Now, AH=DH because FH is a perpendicular bisector; similarly BH = CH. AH=EH because GH is a perpendicular bisector, so DH = EH. And by construction BA = CD = CE. So the triangles ABH, DCH and ECH are congruent, and so the angles ABH, DCH and ECH are equal.

But if the angles DCH and ECH are equal then the angle DCE must be zero.

Q.E.D.

The error in the proof comes in the diagram and the final point. An accurate diagram would show that the triangle ECH is a reflection of the triangle DCH in the line CH rather than being on the same side, and so while the angles DCH and ECH are equal in magnitude, there is no justification for subtracting one from the other; to find the angle DCE you need to subtract the angles DCH and ECH from the angle of a full circle (2π or 360°).

[edit] Proof that any parallelogram has infinite area

Take a parallelogram ABCD. Rule an infinite number of lines equal and parallel to CD along AD's length until ABCD is completely full of these lines. As these lines all equal CD, the total area of these lines (and thus the parallelogram) is ∞ × (CD), thus infinity.

Q.E.D.

The fallacy here is that a line does not represent an area, and can't be used in this way. Also, infinity is not a real number and is not used in conventional geometrical equations.

[edit] Proof that any triangle is isosceles

It is sufficient to prove that any two sides of a triangle are congruent.

Refer to the diagrams at MathPages article.

Given a triangle △ABC, proof that AB = AC:

- Draw a line bisecting ∠A

- Call the midpoint of line segment BC, D

- Draw the perpendicular bisector of segment BC, which contains D

- If these two lines are parallel, AB = AC, by some other theorem; otherwise they intersect at point P

- Draw line PE perpendicular to AB, line PF perpendicular to AC

- Draw lines PB and PC

- By AAS, △EAP ≅ △FAP (AP = AP; ∠PAF ≅ ∠PAE since AP bisects ∠A; ∠AEP ≅ ∠AFP are both right angles)

- By HL, △PDB ≅ △PDC (∠PDB,∠PDC are right angles; PD = PD; BD = CD because PD bisects BC)

- By SAS, △EPB ≅ △FPC (EP = FP since △EAP ≅ △FAP; BP = CP since △PDB ≅ △PDC; ∠EPB ≅ ∠FPC since they are vertical angles)

- Thus, AE ≅ AF, EB ≅ FC, and AB = AE + EB = AF + FC = AC

Q.E.D.

As a corollary, one can show that all triangles are equilateral, by showing that AB = BC and AC = BC in the same way.

All but the last step of the proof is indeed correct (those three triangles are indeed congruent). The error in the proof is the assumption in the diagram that the point P is inside the triangle. In fact, whenever AB ≠ AC, P lies outside the triangle. Furthermore, it can be further shown that, if AB is shorter than AC, then E will lie outside of AB, while F will lie within AC (and vice versa). (Any diagram drawn with sufficiently accurate instruments will verify the above two facts.) Because of this, AB is actually AE - EB, whereas AC is still AF + FC; and thus the lengths are not necessarily the same.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Harro Heuser: Lehrbuch der Analysis - Teil 1, 6th edition, Teubner 1989, ISBN 978-3835101319, page 51 (German).

[edit] External links

- Invalid proofs at Cut-the-knot (including literature references)

- More invalid proofs from AhaJokes.com

- More invalid proofs also on this page

![\sqrt[3] {1-x} + \sqrt[3] {x-3} = 1\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/1/0/e/10e278614064d15d3048b3c45b6d5c83.png)

![(1-x) + 3 \sqrt[3]{1-x} \ \sqrt[3]{x-3} \ (\sqrt[3]{1-x} + \sqrt[3]{x-3}) + (x-3) = 1\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/d/d/0/dd0ba2c0c1618ddba2dab51629df18c5.png)

![-2 + 3 \sqrt[3]{1-x} \ \sqrt[3]{x-3} = 1\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/1/d/8/1d8da54653fbced2d2a4fc0ed4eb21af.png)

![\sqrt[3]{1-x} \ \sqrt[3]{x-3} = 1\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/c/7/0/c70502e2f1da83ab9ec9ac7a06c1ed72.png)

![\sqrt[3] {1-2} + \sqrt[3] {2-3} = 1\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/0/0/f002b74f3a0e24bb4e1c5a8fc52e2f9d.png)

![\frac{}{}\infin = [\infin - (-\infin)]^2](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/9/2/e/92ee12fcf4b5ff4875709368ef89ca92.png)

![\frac{1}{4} = \left[\frac{1}{4} - \left(-\frac{1}{4}\right)\right]^2](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/f/9/bf9e306f0134dada0247d2c40bcc9b7d.png)

![\frac{1}{4} = \left[\frac{1}{2}\right]^2](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/5/b/75bdcedec38cab61e6c806c2d8219e04.png)