Maximum likelihood

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is a popular statistical method used for fitting a mathematical model to data. The modeling of real world data using estimation by maximum likelihood offers a way of tuning the free parameters of the model to provide a good fit.

The method was pioneered by geneticist and statistician Sir R. A. Fisher between 1912 and 1922.

The method of maximum likelihood corresponds to many well-known estimation methods in statistics. For example, suppose you are interested in the heights of Americans. You have a sample of some number of Americans, but not the entire population, and record their heights. Further, you are willing to assume that heights are normally distributed with some unknown mean and variance. The sample mean is then the maximum likelihood estimator of the population mean, and the sample variance is a close approximation to the maximum likelihood estimator of the population variance (see examples below).

For a fixed set of data and underlying probability model, maximum likelihood picks the values of the model parameters that make the data "more likely" than any other values of the parameters would make them. Maximum likelihood estimation gives a unique and easy way to determine solution in the case of the normal distribution and many other problems, although in very complex problems this may not be the case. If a uniform prior distribution is assumed over the parameters, the maximum likelihood estimate coincides with the most probable values thereof.

Contents |

[edit] Motivational example

As a motivational example, let X be a binomial random variable with n = 10 and an unknown parameter p. Further suppose that x = 3, a realization of the random variable X, is observed. As in all estimation problems, the goal is to estimate the unknown parameter p. The fundamental idea in maximum likelihood estimation is to calculate the probability of generating the observed value x = 3, that is, P(X = 3), under the different possible values that p can take. By construction of the binomial distribution, p is a probability and therefore ![p \in [0, 1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/5/0/550abf67410399d394e58560a62f657a.png) . In order to calculate these probabilities, we view the binomial distribution as a function of p, holding x fixed at 3 :

. In order to calculate these probabilities, we view the binomial distribution as a function of p, holding x fixed at 3 :

In this example, L is the likelihood function. Here is a plot a of L:

As can be seen on the graph, it turns out that the probability of generating x = 3 is the largest when p = 0.3. Hence  will be the maximum likelihood estimate of p. Of course, in general, inference will not be based on a single observed value x but on a random sample

will be the maximum likelihood estimate of p. Of course, in general, inference will not be based on a single observed value x but on a random sample  yielding observations

yielding observations  . Supposing that the random variables

. Supposing that the random variables  are independent and identically distributed, the likelihood function is a product of binomial densities, regarded as a function of p.

are independent and identically distributed, the likelihood function is a product of binomial densities, regarded as a function of p.

[edit] Principles

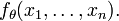

Consider a family Dθ of probability distributions parameterized by an unknown parameter θ (which could be vector-valued), associated with either a known probability density function (continuous distribution) or a known probability mass function (discrete distribution), denoted as fθ. We draw a sample  of n values from this distribution, and then using fθ we compute the (multivariate) probability density associated with our observed data,

of n values from this distribution, and then using fθ we compute the (multivariate) probability density associated with our observed data,

As a function of θ with x1, ..., xn fixed, this is the likelihood function

The method of maximum likelihood estimates θ by finding the value of θ that maximizes  . This is the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) of θ:

. This is the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) of θ:

From a simple point of view, the outcome of a maximum likelihood analysis is the maximum likelihood estimate. This can be supplemented by an approximation for the covariance matrix of the MLE, where this approximation is derived from the likelihood function. A more complete outcome from a maximum likelihood analysis would be the likelihood function itself, which can be used to construct improved versions of confidence intervals compared to those obtained from the approximate variance matrix. See also Likelihood Ratio Test.

Commonly, one assumes that the data drawn from a particular distribution are independent, identically distributed (iid) with unknown parameters. This considerably simplifies the problem because the likelihood can then be written as a product of n univariate probability densities:

and since maxima are unaffected by monotone transformations, one can take the logarithm of this expression to turn it into a sum:

The maximum of this expression can then be found numerically using various optimization algorithms.

This contrasts with seeking an unbiased estimator of θ, which may not necessarily yield the MLE but which will yield a value that (on average) will neither tend to over-estimate nor under-estimate the true value of θ.[citation needed]

Note that the maximum likelihood estimator may not be unique, or indeed may not even exist.

[edit] Properties

[edit] Functional invariance

The maximum likelihood estimator selects the parameter value which gives the observed data the largest possible probability (or probability density, in the continuous case). If the parameter consists of a number of components, then we define their separate maximum likelihood estimators, as the corresponding component of the MLE of the complete parameter. Consistent with this, if  is the MLE for θ, and if g is any function of θ, then the MLE for α = g(θ) is by definition

is the MLE for θ, and if g is any function of θ, then the MLE for α = g(θ) is by definition

It maximizes the so-called profile likelihood:

[edit] Bias

For small samples, the bias of maximum-likelihood estimators can be substantial.

[edit] Example

Consider a case where n tickets numbered from 1 to n are placed in a box and one is selected at random (see uniform distribution); thus, the sample size is 1). If n is unknown, then the maximum-likelihood estimator  of n is the number m on the drawn ticket. (The likelihood is 0 for n < m, 1/n for n ≥ m, and this is greatest when n = m. Note that the maximum likelihood estimate of n occurs at the lower extreme of possible values {m, m + 1, ...}, rather than somewhere in the "middle" of the range of possible values, which would result in less bias.) The expected value of the number m on the drawn ticket, and therefore the expected value of

of n is the number m on the drawn ticket. (The likelihood is 0 for n < m, 1/n for n ≥ m, and this is greatest when n = m. Note that the maximum likelihood estimate of n occurs at the lower extreme of possible values {m, m + 1, ...}, rather than somewhere in the "middle" of the range of possible values, which would result in less bias.) The expected value of the number m on the drawn ticket, and therefore the expected value of  , is (n + 1)/2. As a result, the maximum likelihood estimator for n will systematically underestimate n by (n − 1)/2 with a sample size of 1.

, is (n + 1)/2. As a result, the maximum likelihood estimator for n will systematically underestimate n by (n − 1)/2 with a sample size of 1.

[edit] Asymptotics

In many cases, estimation is performed using a set of independent identically distributed measurements. These may correspond to distinct elements from a random sample, repeated observations, etc. In such cases, it is of interest to determine the behavior of a given estimator as the number of measurements increases to infinity, referred to as asymptotic behaviour.

Under certain (fairly weak) regularity conditions, which are listed below, the MLE exhibits several characteristics which can be interpreted to mean that it is "asymptotically optimal". These characteristics include:

- The MLE is asymptotically unbiased, i.e., its bias tends to zero as the sample size increases to infinity.

- The MLE is asymptotically efficient, i.e., it achieves the Cramér-Rao lower bound when the sample size tends to infinity. This means that no asymptotically unbiased estimator has lower asymptotic mean squared error than the MLE.

- The MLE is asymptotically normal. As the sample size increases, the distribution of the MLE tends to the Gaussian distribution with mean θ and covariance matrix equal to the inverse of the Fisher information matrix.

Since the Cramér-Rao bound only speaks of unbiased estimators while the maximum likelihood estimator is usually biased, asymptotic efficiency as defined here does not mean anything: perhaps there are other nearly unbiased estimators with much smaller variance. However, it can be shown that among all regular estimators, which are estimators which have an asymptotic distribution which is not dramatically disturbed by small changes in the parameters, the asymptotic distribution of the maximum likelihood estimator is the best possible, i.e., most concentrated. [1]

Some regularity conditions which ensure this behavior are:

- The first and second derivatives of the log-likelihood function must be defined.

- The Fisher information matrix must not be zero, and must be continuous as a function of the parameter.

- The maximum likelihood estimator is consistent.

By the mathematical meaning of the word asymptotic, asymptotic properties are properties which only approached in the limit of larger and larger samples: they are approximately true when the sample size is large enough. The theory does not tell us how large the sample needs to be in order to obtain a good enough degree of approximation. Fortunately, in practice they often appear to be approximately true, when the sample size is moderately large. So in practice, inference about the estimated parameters is often based on the asymptotic Gaussian distribution of the MLE. When we do this, the Fisher information matrix is usefully estimated by the observed information matrix.

Some cases where the asymptotic behaviour described above does not hold are outlined next.

Estimate on boundary. Sometimes the maximum likelihood estimate lies on the boundary of the set of possible parameters, or (if the boundary is not, strictly speaking, allowed) the likelihood gets larger and larger as the parameter approaches the boundary. Standard asymptotic theory needs the assumption that the true parameter value lies away from the boundary. If we have enough data, the maximum likelihood estimate will keep away from the boundary too. But with smaller samples, the estimate can lie on the boundary. In such cases, the asymptotic theory clearly does not give a practically useful approximation. Examples here would be variance-component models, where each component of variance, σ2, must satisfy the constraint σ2 ≥0.

Data boundary parameter-dependent. For the theory to apply in a simple way, the set of data values which has positive probability (or positive probability density) should not depend on the unknown parameter. A simple example where such parameter-dependence does hold is the case of estimating θ from a set of independent identically distributed when the common distribution is uniform on the range (0,θ). For estimation purposes the relevant range of θ is such that θ cannot be less than the largest observation. In this instance the maximum likelihood estimate exists and has some good behaviour, but the asymptotics are not as outlined above.

Nuisance parameters. For maximum likelihood estimations, a model may have a number of nuisance parameters. For the asymptotic behaviour outlined to hold, the number of nuisance parameters should not increase with the number of observations (the sample size). A well-known example of this case is where observations occur as pairs, where the observations in each pair have a different (unknown) mean but otherwise the observations are independent and Normally distributed with a common variance. Here for 2N observations, there are N+1 parameters. It is well-known that the maximum likelihood estimate for the variance does not converge to the true value of the variance.

Increasing information. For the asymptotics to hold in cases where the assumption of independent identically distributed observations does not hold, a basic requirement is that the amount of information in the data increases indefinitely as the sample size increases. Such a requirement may not be met if either there is too much dependence in the data (for example, if new observations are essentially identical to existing observations), or if new independent observations are subject to an increasing observation error.

[edit] Examples

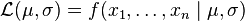

[edit] Discrete distribution, finite parameter space

Consider tossing an unfair coin 80 times (i.e., we sample something like x1=H, x2=T, ..., x80=T, and count the number of HEADS "H" observed). Call the probability of tossing a HEAD p, and the probability of tossing TAILS 1-p (so here p is θ above). Suppose we toss 49 HEADS and 31 TAILS, and suppose the coin was taken from a box containing three coins: one which gives HEADS with probability p=1/3, one which gives HEADS with probability p=1/2 and another which gives HEADS with probability p=2/3. The coins have lost their labels, so we don't know which one it was. Using maximum likelihood estimation we can calculate which coin has the largest likelihood, given the data that we observed. The likelihood function (defined below) takes one of three values:

We see that the likelihood is maximized when p=2/3, and so this is our maximum likelihood estimate for p.

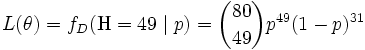

[edit] Discrete distribution, continuous parameter space

Now suppose we had only one coin but its p could have been any value 0 ≤ p ≤ 1. We must maximize the likelihood function:

over all possible values 0 ≤ p ≤ 1.

One way to maximize this function is by differentiating with respect to p and setting to zero:

which has solutions p=0, p=1, and p=49/80. The solution which maximizes the likelihood is clearly p=49/80 (since p=0 and p=1 result in a likelihood of zero). Thus we say the maximum likelihood estimator for p is 49/80.

This result is easily generalized by substituting a letter such as t in the place of 49 to represent the observed number of 'successes' of our Bernoulli trials, and a letter such as n in the place of 80 to represent the number of Bernoulli trials. Exactly the same calculation yields the maximum likelihood estimator t / n for any sequence of n Bernoulli trials resulting in t 'successes'.

[edit] Continuous distribution, continuous parameter space

For the normal distribution  which has probability density function

which has probability density function

the corresponding probability density function for a sample of n independent identically distributed normal random variables (the likelihood) is

or more conveniently:

,

,

where  is the sample mean.

is the sample mean.

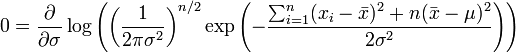

This family of distributions has two parameters: θ=(μ,σ), so we maximize the likelihood,  , over both parameters simultaneously, or if possible, individually.

, over both parameters simultaneously, or if possible, individually.

Since the logarithm is a continuous strictly increasing function over the range of the likelihood, the values which maximize the likelihood will also maximize its logarithm. Since maximizing the logarithm often requires simpler algebra, it is the logarithm which is maximized below. (Note: the log-likelihood is closely related to information entropy and Fisher information.)

which is solved by

.

.

This is indeed the maximum of the function since it is the only turning point in μ and the second derivative is strictly less than zero. Its expectation value is equal to the parameter μ of the given distribution,

which means that the maximum-likelihood estimator  is unbiased.

is unbiased.

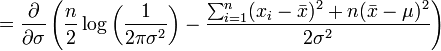

Similarly we differentiate the log likelihood with respect to σ and equate to zero:

which is solved by

.

.

Inserting  we obtain

we obtain

.

.

To calculate its expected value, it is convenient to rewrite the expression in terms of zero-mean random variables (statistical error)  . Expressing the estimate in these variables yields

. Expressing the estimate in these variables yields

.

.

Simplifying the expression above, utilizing the facts that ![E\left[\delta_i\right] = 0](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/1/e/8/1e8fa4403ce5626dcd6288f3b46b9e79.png) and

and ![E[\delta_i^2] = \sigma^2](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/7/0/a/70a488218f5c06e05db0900b82dce630.png) , allows us to obtain

, allows us to obtain

![E \left[ \widehat{\sigma^2} \right]= \frac{n-1}{n}\sigma^2](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/1/9/f195158a4533fd75a7a7a150813cfc16.png) .

.

This means that the estimator  is biased (However,

is biased (However,  is consistent).

is consistent).

Formally we say that the maximum likelihood estimator for θ = (μ,σ2) is:

In this case the MLEs could be obtained individually. In general this may not be the case, and the MLEs would have to be obtained simultaneously.

[edit] Non-independent variables

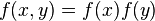

It may be the case that variables are correlated, in which case they are not independent. Two random variables X and Y are independent only if their joint probability density function is the product of the individual probability density functions, i.e.

Suppose one constructs an order-n Gaussian vector out of random variables  , where each variable has means given by

, where each variable has means given by  . Furthermore, let the covariance matrix be denoted by Σ,

. Furthermore, let the covariance matrix be denoted by Σ,

The joint probability density function of these n random variables is then given by:

In the two variable case, the joint probability density function is given by:

In this and other cases where a joint density function exists, the likelihood function is defined as above, under Principles, using this density.

[edit] Applications

Maximum likelihood estimation is used for a wide range of statistical models, including:

-

- linear models and generalized linear models;

- exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis;

- structural equation modeling;

- many situations in the context of hypothesis testing and confidence interval formation.

These uses arise across applications in widespead set of fields, including:

-

- communication systems;

- psychometrics and econometrics;

- time-delay of arrival (TDOA) in acoustic or electromagnetic detection;

- data modeling in nuclear and particle physics;

- computational phylogenetics;

- origin/destination and path-choice modeling in transport networks.

[edit] See also

- Abductive reasoning, a logical technique corresponding to maximum likelihood.

- Censoring (statistics)

- Delta method, a method for finding the distribution of functions of a maximum likelihood estimator.

- Generalized method of moments, a method related to maximum likelihood estimation.

- Inferential statistics, for an alternative to the maximum likelihood estimate.

- Likelihood function, a description on what likelihood functions are.

- Maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimator, for a contrast in the way to calculate estimators when prior knowledge is postulated.

- Maximum spacing estimation, a related method that is more robust in many situations.

- Mean squared error, a measure of how 'good' an estimator of a distributional parameter is (be it the maximum likelihood estimator or some other estimator).

- Method of moments (statistics), for another popular method for finding parameters of distributions.

- Method of support, a variation of the maximum likelihood technique.

- Minimum distance estimation

- Quasi-maximum likelihood estimator, a MLE estimator that is misspecified, but still consistent.

- The Rao–Blackwell theorem, a result which yields a process for finding the best possible unbiased estimator (in the sense of having minimal mean squared error). The MLE is often a good starting place for the process.

- Sufficient statistic, a function of the data through which the MLE (if it exists and is unique) will depend on the data.

[edit] References

- ^ A.W. van der Vaart, Asymptotic Statistics (Cambridge Series in Statistical and Probabilistic Mathematics) (1998)

- Kay, Steven M. (1993). Fundamentals of Statistical Signal Processing: Estimation Theory. Prentice Hall. pp. Ch. 7. ISBN 0-13-345711-7.

- Lehmann, E. L.; Casella, G. (1998). Theory of Point Estimation. Springer. pp. 2nd ed. ISBN 0-387-98502-6.

- A paper on the history of Maximum Likelihood: Aldrich, John (1997). "R.A. Fisher and the making of maximum likelihood 1912-1922". Statistical Science 12 (3): 162–176. doi:. http://projecteuclid.org/Dienst/UI/1.0/Summarize/euclid.ss/1030037906.

- M. I. Ribeiro, Gaussian Probability Density Functions: Properties and Error Characterization (Accessed 19 March 2008)

[edit] External links

- Maximum Likelihood Estimation Primer (an excellent tutorial)

- Implementing MLE for your own likelihood function using R

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![L : [0, 1] \longmapsto \mathbf{R}, \; p \longmapsto \frac{10!}{3!(10 - 3)!} p^3 (1 - p)^{10 - 3} = 120 p^3 (1 - p)^7.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/9/4/294cfb4a48c07045d1b47e7117fdce0e.png)

![\begin{align}

{0}&{} = \frac{\partial}{\partial p} \left( \binom{80}{49} p^{49}(1-p)^{31} \right) \\

& {}\propto 49p^{48}(1-p)^{31} - 31p^{49}(1-p)^{30} \\

& {}= p^{48}(1-p)^{30}\left[ 49(1-p) - 31p \right] \\

& {}= p^{48}(1-p)^{30}\left[ 49 - 80p \right]

\end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/3/2/7/327ff4afbca81a71505cbcedad0f0173.png)

![E \left[ \widehat\mu \right] = \mu,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/a/4/fa43fb90273a7e483bd044c13fab190c.png)

![f(x_1,\ldots,x_n)=\frac{1}{(2\pi)^{n/2}\sqrt{\text{det}(\Sigma)}} \exp\left( -\frac{1}{2} \left[x_1-\mu_1,\ldots,x_n-\mu_n\right]\Sigma^{-1} \left[x_1-\mu_1,\ldots,x_n-\mu_n\right]^T \right)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/e/2/8/e28f5f95dcc04dff99de4ac2c719c596.png)

![f(x,y) = \frac{1}{2\pi \sigma_x \sigma_y \sqrt{1-\rho^2}} \exp\left[ -\frac{1}{2(1-\rho^2)} \left(\frac{(x-\mu_x)^2}{\sigma_x^2} - \frac{2\rho(x-\mu_x)(y-\mu_y)}{\sigma_x\sigma_y} + \frac{(y-\mu_y)^2}{\sigma_y^2}\right) \right]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/f/d/e/fde247acd0fcb4158054abc305e5e2aa.png)