Ignaz Semmelweis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- The Hungarian form of this personal name is Semmelweis Ignác Fülöp. This article uses the Western name order.

| Ignaz Semmelweis | |

Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis.

Pen-drawing by Jenő Doby, showing Semmelweis 1860, age 42. |

|

| Born | July 1, 1818 Buda, Hungary |

|---|---|

| Died | August 13, 1865 Vienna, Austria |

| Nationality | Hungarian, Austrian (Austro-Hungarian) |

| Fields | Obstetrics |

| Known for | Hand washing standards in obstetrical clinics |

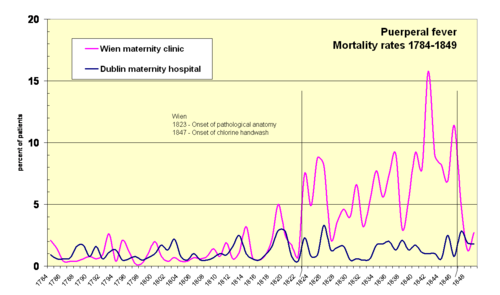

Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis[1] (1818 – 1865) was a Hungarian physician. He discovered that cases of puerperal fever, also known as childbed fever, could be cut drastically if doctors washed their hands in a chlorine solution before gynaecological examinations.

While employed as assistant to the professor of the maternity clinic at the Vienna General Hospital in Austria in 1847, Semmelweis introduced hand washing with chlorinated lime solutions for interns who had performed autopsies. This immediately reduced the incidence of fatal puerperal fever from about 10 percent (range 5–30 percent) to about 1–2 percent. At the time, diseases were attributed to many different and unrelated causes. Each case was considered unique, just like a human person is unique. Semmelweis' hypothesis, that there was only one cause, that all that mattered was cleanliness, was extreme at the time, and was largely ignored, rejected or ridiculed. He was dismissed from the hospital and harassed by the medical community in Vienna, which eventually forced him to move to Pest.

Semmelweis was outraged by the indifference of the medical profession and began writing open and increasingly angry letters to prominent European obstetricians, at times denouncing them as irresponsible murderers. His contemporaries, including his wife, believed he was losing his mind, and in 1865 he was committed to an asylum. He died there only 14 days later, possibly after being severely beaten by guards. Semmelweis' practice only earned widespread acceptance years after his death, when Louis Pasteur developed the germ theory of disease which offered a theoretical explanation for Semmelweis' findings. He is considered a pioneer of antiseptic procedures.

[edit] Parents and early life

Ignaz Semmelweis was born on July 1, 1818 in Tabán, a sector of what is now Budapest. It was then part of the Habsburg empire, now Hungary. He was the fifth child out of ten of a prosperous grocer family of József and Terézia Müller Semmelweis. The family was German-speaking and perhaps Jewish.[2]

His father, József Semmelweis (1778–1846), was born in Kismarton, Kingdom of Hungary, Austrian Empire (today Eisenstadt, Austria). József achieved permission to set up shop in Buda in 1806[3] and, in the same year, opened a wholesale business with spices and general consumer goods[4] named zum Weißen Elephanten (the White Elephant) in Heindl-Haus in Tabán (today a museum). By 1810, he was a wealthy man when he married Terézia Müller, daughter of the famous vehicle builder Fülöp Müller.[5]

Semmelweis began studying law at the University of Vienna in the autumn of 1837, but by the following year, for reasons that are no longer known, he had changed to medicine. He was awarded his doctorate degree in medicine in 1844. After failing to obtain an appointment in a clinic for internal medicine, Semmelweis decided to specialize in obstetrics. [6] Some of his teachers included Carl von Rokitansky, Josef Skoda and Ferdinand von Hebra.

|

Child portrait of Ignác Semmelweis from 1830. Oil painting by Lénart Landau (1790–1868), a painter from Pest |

[edit] Discovery of cadaverous poisoning

Semmelweis was appointed assistant to Professor Klein in the 'First Obstetrical Clinic of the Vienna General Hospital on the 1st July 1846.[7] A comparable position today would be "head resident".[8] His duties were, amongst others, to examine patients each morning in preparation for the professor's rounds, supervise difficult deliveries and teach obstetrical students. He was also responsible for the clerical records.

Maternity institutions were set up all over Europe to address problems of infanticide of "illegitimate" children. They were set up as gratis institutions and offered to care for the infants, which made them attractive to underprivileged women, including prostitutes. In return for the free services, the women would subject themselves to the training of doctors and midwives. There were two maternity clinics at the Viennese hospital. The First Clinic had an average maternal mortality rate due to puerperal fever of about 10% (actual rates fluctuated wildly). The Second Clinic's rate was considerably lower, averaging less than 4%. This fact was known outside the hospital. The two clinics admitted on alternate days but women begged to be admitted to the Second Clinic due to the bad reputation of the First Clinic.[9] Semmelweis described desperate women begging on their knees not to be admitted to the First Clinic.[10] Some women even preferred to give birth in the streets, pretending to have given sudden birth en route to the hospital (a practice known as street births), which meant they would still qualify for the child care benefits without having been admitted to the clinic. Semmelweis was puzzled that puerperal fever was rare amongst women giving street births. "To me, it appeared logical that patients who experienced street births would become ill at least as frequently as those who delivered in the clinic. [...] What protected those who delivered outside the clinic from these destructive unknown endemic influences?"[11]

Semmelweis was severely troubled and literally sickened that his First Clinic had a much higher mortality rate due to puerperal fever than the Second Clinic. It "made me so miserable that life seemed worthless".[12] The two clinics used almost the same techniques, and Semmelweis started a meticulous work eliminating all possible differences, even including religious practices. The only major difference was the individuals who worked there. The First Clinic was the teaching service for medical students, while the Second Clinic had been selected in 1841 for the instruction of midwives only.

| First clinic | Second clinic | ||||||

| Year | Births | Deaths | Rate (%) | Births | Deaths | Rate (%) | |

| 1841 | 3,036 | 237 | 7.8 | 2,442 | 86 | 3.5 | |

| 1842 | 3,287 | 518 | 15.8 | 2,659 | 202 | 7.6 | |

| 1843 | 3,060 | 274 | 9.0 | 2,739 | 164 | 6.0 | |

| 1844 | 3,157 | 260 | 8.2 | 2,956 | 68 | 2.3 | |

| 1845 | 3,492 | 241 | 6.9 | 3,241 | 66 | 2.0 | |

| 1846 | 4,010 | 459 | 11.4 | 3,754 | 105 | 2.8 | |

He excluded "overcrowding" as a cause because the Second Clinic was always more crowded as stated above but the mortality was lower. He eliminated climate as a cause because the climate was not different, and so on. The breakthrough for Ignaz Semmelweis occurred in 1847 following the death of his good friend Jakob Kolletschka who had been accidentally poked with a student's scalpel while performing a postmortem examination. Kolletschka's own autopsy showed a pathological situation similar to that of the women who were dying from puerperal fever. Semmelweis immediately proposed a connection between cadaveric contamination and puerperal fever.

He concluded that he and the medical students carried "cadaverous particles" on their hands[13] from the autopsy room to the patients they examined in the First Obstetrical Clinic. This explained why the student midwives in the Second Clinic who were not engaged in autopsies and had no contact with corpses experienced a much lower mortality rate. There were still opportunities for midwives to contaminate their hands, however. In a lecture in 1846 Jakob Kolletschka is reputed to have said, "It is here no uncommon thing for midwives, especially in the commencement of their practice, to pull off legs and arms of infants, and even to pull away the entire body and leave the head in the uterus. Such occurrences are not altogether uncommon; they often happen."[14]

The germ theory of disease had not yet been developed at the time. Thus, Semmelweis concluded that some unknown "cadaverous material" caused childbed fever. He instituted a policy of using a solution of chlorinated lime for washing hands between autopsy work and the examination of patients and the mortality rate dropped ten-fold, comparable to the Second Clinic's. The mortality rate in April 1847 was 18.3 percent, handwashing was instituted mid-May, the rates in June were 2.2 percent, July 1.2 percent, August 1.9 percent and, for the first time since the introduction of anatomical orientation, the death rate was zero in two months in the year following this discovery.

[edit] Ideas ran contrary to established medical opinion

Semmelweis' observations went against all established scientific medical opinion of the time. The theory of diseases was highly influenced by ideas of an imbalance of the basic "four humours" in the body, a theory known as dyscrasia, for which the main treatment was bloodlettings. Medical texts at the time emphasized that each case of disease was unique, the result of a personal imbalance, and the main difficulty of the medical profession was to establish precisely each patient's unique situation, case by case.

The findings from autopsies of deceased women also showed a confusing multitude of various physical signs, which emphasised the belief that puerperal fever was not one, but many different, yet unidentified, diseases. Semmmelweis' main finding — that all instances of puerperal fever could be traced back to only one single cause: lack of cleanliness — was simply unacceptable. His findings also ran against the conventional wisdom that diseases spread in the form of "bad air", also known as miasmas or vaguely as "unfavourable atmospheric-cosmic-terrestrial influences". Semmelweis' groundbreaking idea — that harmful infectious particles could sit in minuscule amounts on fingers — was contrary to all established medical understanding.

As a result, his ideas were rejected by the medical community. Other more subtle factors may also have played a role. Some doctors, for instance, were offended at the suggestion that they should wash their hands; they felt that their social status as gentlemen was inconsistent with the idea that their hands could be unclean.[15]

Specifically, Semmelweis' claims were thought to lack scientific basis, since he could offer no acceptable explanation for his findings. Such a scientific explanation was made possible only some decades later when the germ theory of disease was developed by Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, and others.

During 1848 Ignaz Semmelweis widened the scope of his washing protocol to include all instruments coming in contact with patients in labor, and used mortality-rate time series to document his success in virtually eliminating puerperal fever from the hospital ward.

[edit] Hesitant publication of results and first signs of trouble

Toward the end of 1847, accounts of Semmelweis's work began to spread around Europe. Semmelweis and his students wrote letters to the directors of several prominent maternity clinics describing their recent observations. Ferdinand von Hebra, the editor of a leading Austrian medical journal, announced Semmelweis's discovery in the December 1847[16] and April 1848[17] issues of the medical journal. Hebra claimed that Semmelweis's work had a practical significance comparable to that of Edward Jenner's introduction of cowpox inoculations to prevent smallpox.[18]

In late 1848, one of Semmelweis' former students wrote a lecture explaining Semmelweis' work. The lecture was presented before the Royal Medical and Surgical Society in London and a review published in the Lancet, a prominent medical journal.[19] A few months later, another of Semmelweis's former students published a similar essay in a French periodical.[20]

As accounts of the dramatic reduction in mortality rates in Vienna were being circulated throughout Europe, Semmelweis had reason to expect that the chlorine washings would be widely adopted, saving tens of thousands of lives. Early responses to his work also gave clear signs of coming trouble, however. Some physicians had clearly misinterpreted his claims. James Young Simpson, for instance, saw no difference between Semmelweis' groundbreaking findings and the British idea suggested by Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1843 that childbed fever was contagious (i.e. that infected persons could pass the infection to others).[21] Indeed, initial responses to Semmelweis' findings were that he had said nothing new.[22]

In fact, Semmelweis was warning against all decaying organic matter — not just against a specific contagion that originated from victims of childbed fever themselves. This misunderstanding, and others like it, occurred partly because Semmelweis's work was known only through secondhand reports written by his colleagues and students. At this crucial stage, Semmelweis himself published nothing. These and similar misinterpretations would continue to cloud discussions of his work throughout the century.[23]

Some accounts emphasise that Semmelweis refused to communicate his method officially to the learned circles of Vienna,[24] nor was he eager to explain it on paper.

[edit] Political turmoil and dismissal from the Vienna hospital

In 1848 a series of tumultous revolutions swept across Europe. The resulting political turmoil would affect Semmelweis' career. In Vienna on 13 March 1848, students demonstrated in favor of increased civil rights, including trial by jury and freedom of expression. The demonstration was led by medical students and young faculty members and were joined by workers from the suburbs. Two days later in Hungary, demonstrations and uprisings led to the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and a full scale war against the ruling Habsburgs of the Austrian Empire. In Vienna, the March demonstration was followed by months of general unrest.[25]

There is no evidence that Semmelweis was personally involved in the events of 1848. It is known that some of his brothers were punished for active participation in the Hungarian independence movement, and it seems likely that the Hungarian born Semmelweis was sympathetic to the cause. Semmelweis's superior, professor Johann Klein, is described as a conservative Austrian, likely at unease with the independence movements and at alarmed with the other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. It seems likely that Klein mistrusted Semmelweis.[26]

When Semmelweis' term was about to expire Carl Braun also applied for the position of assistant in the First Clinic, possibly at Klein's own invitation. Semmelweis and Braun were the only two applicants for the post. Semmelweis's predecessor, Breit, had been granted a two-year extension[27] . Semmelweis's application for an extension was supported by Josef Škoda and Carl von Rokitansky and by most of the medical faculty. But Klein chose Braun for the position. Semmelweis was obliged to leave the obstetrical clinic when his term expired on 20 March 1849.[28]

The day his term expired, Semmelweis petitioned the Viennese authorities to be made docent of obstetrics. A docent was a private lecturer who taught students and who had access to some university facilities. At first, because of Klein's opposition, Semmelweis's petition was denied. He reapplied, but had to wait until 10 Oct 1850 (almost 1½ year) before finally being appointed docent of theoretical obstetrics[29]. The terms refused him access to cadavers and limited him to teaching students by using leather fabricated mannequins only. A few days after being notified of his appointment, Semmelweis left Vienna abruptly and returned to Pest. It appears that he left without so much as saying good-bye to his former friends and colleagues, a move which may have offended them[30]. According to his own account, he left Vienna because he was "unable to endure further frustrations in dealing with the Viennese medical establishment".[31]

[edit] Life in Pest-Buda (since 1873 Budapest)

During 1848–1849 some 70,000 troops from the Habsburg-ruled Austrian Empire thwarted the Hungarian independence movement, executed or imprisoned its leaders and in the process destroyed parts of Pest. It seems likely that Semmelweis, upon arriving from the Habsburg Vienna in 1850, was not warmly welcomed in Pest.

On 20 May 1851 Semmelweis took the relatively insignificant position of unpaid, honorary head physician of the obstetric ward of Pest's small St. Rochus Hospital. He held that position for six years, until June 1857. [32] [33] Childbed fever was rampant at the clinic; at a visit in 1850, just after returning to Pest, Semmelweis found one fresh corpse, another patient in severe agony, and four others seriously ill with the disease. After taking over in 1851, Semmelweis virtually eliminated the disease. During 1851–1855 only 8 patients died from childbed fever out of 933 births (0.85 percent).[34]

Despite the impressive results, Semmelweis's ideas were not accepted by the other obstetricians in Budapest.[35] The professor of obstetrics at the University of Pest, Ede Flórián Birly, never adopted Semmelweis' methods. He continued to believe that puerperal fever was due to uncleanliness of the bowel.[36] Therefore, extensive purges was the preferred treatment.

After professor Birly died in 1854, Semmelweis applied for the position. So did Carl Braun — Semmelweis's nemesis and successor as Johann Klein's assistant in Vienna — and Braun received more votes from his Hungarian colleagues than Semmelweis did. Semmelweis was eventually appointed in 1855, but only because the Viennese authorities overruled the wishes of the Hungarians because Braun did not speak Hungarian. As professor of obstetrics, Semmelweis instituted chlorine washings at the University of Pest maternity clinic. Once again he attained impressive results[35].

Semmelweis had now achieved dramatic successes at three obstetrical facilities — even so, his ideas continued to be ridiculed and rejected both in Vienna and in Pest-Buda.

He built a large private practice[citation needed]. Semmelweis turned down an offer in 1857 to become professor of obstetrics at the University of Zurich.[37] The same year, Semmelweis married the nineteen years younger Mária Weidenhoffer (1837–1910). She was the daughter of a successful merchant in Pest.[38]

|

Carl Braun, Semmelweis' nemesis, picture approx. 1880 |

[edit] Rejection by the medical community

- One of the first to respond to Semmelweis' 1848 communications was James Young Simpson who wrote a stinging letter. Simpson surmised that the English obstetrical literature must be totally unknown in Vienna, otherwise Semmelweis would have known that the English have long regarded childbed fever as contagious and would have employed chlorine washings to protect against it.[39]

- Semmelweis's views were much more favorably received in England than on the continent, but he was more often cited than understood. The English consistently regarded Semmelweis as having supported their theory of contagion. A typical example was W. Tyler Smith who claimed that Semmelweis "made out very conclusively" that "miasms derived from the dissecting room will excite puerperal disease."[40]

- In 1856, Semmelweis' assistant József Fleischer reported the successful results of handwashings at St. Rochus and Pest maternity institutions in the Viennese Medical Weekly (Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift)[35]. The editor remarked sarcastically that it was time people stopped being misled about the theory of chlorine washings.[41] A popular translation into English is "it was time to stop the nonsense of hand washing with chlorine", e.g. found Encyclopedia Britannica.[42] There is little support for the nonsense translation however.[43]

In 1858 Semmelweis finally published his own account of his work in an essay entitled, "The Etiology of Childbed Fever".[44] Two years later he published a second essay, "The Difference in Opinion between Myself and the English Physicians regarding Childbed Fever".[45] In 1861, Semmelweis finally published his main work "Die Ätiologie, der Begriff und die Prophylaxis des Kindbettfiebers" (German for "The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever").

In his 1861 book, Semmelweis lamented the slow adoption of his ideas: "Most medical lecture halls continue to resound with lectures on epidemic childbed fever and with discourses against my theories. […] The medical literature for the last twelve years continues to swell with reports of puerperal epidemics, and in 1854 in Vienna, the birthplace of my theory, 400 maternity patients died from childbed fever. In published medical works my teachings are either ignored or attacked. The medical faculty at Würzburg awarded a prize to a monograph[46] written in 1859 in which my teachings were rejected". [47]

- In Berlin, the professor of obstetrics, Joseph Hermann Schmidt, approved of obstetrical students having ready access to morgues in which they could spend time while waiting for the labor process.[48]

- In a textbook, Carl Braun, Semmelweis's successor as assistant in the first clinic, identified 30 causes of childbed fever; only the 28th of these was cadaverous infection. Other causes included conception and pregnancy, uremia, pressure exerted on adjacent organs by the shrinking uterus, emotional traumata, mistakes in diet, chilling, and atmospheric epidemic influences. [49] The impact of Braun's views are clearly visible in the rising mortality rates in the 1850s.

- Ede Flórián Birly, Semmelweis' predecessor as Professor of Obstetrics at the University of Pest, never accepted Semmelweis' teachings; he continued to believe that puerperal fever was due to uncleanliness of the bowel. [50]

- August Breisky, an obstetrician in Prague, rejected Semmelweis's book as "naive" and he referred to it as "the Koran of puerperal theology". Breisky objected that Semmelweis had not proved that puerperal fever and pyemia are identical, and he insisted that other factors beyond decaying organic matter certainly had to be included in the etiology of the disease. [51]

- Carl Edvard Marius Levy, head of the Copenhagen maternity hospital and an outspoken critic of Semmelweis' ideas, had reservations concerning the unspecific nature of cadaverous particles and that the supposed quantities were unreasonably small. "If Dr. Semmelweis had limited his opinion regarding infections from corpses to puerperal corpses, I would have been less disposed to denial than I am. […] And, with due respect for the cleanliness of the Viennese students, it seems improbable that enough infective matter or vapor could be secluded around the fingernails to kill a patient." [52] In fact, Robert Koch later used precisely this fact to prove that various infecting materials contained living organisms which could reproduce in the human body, i.e. that since the poison could be neither chemical nor physical in operation, it must be biological. [53]

- At a conference of German physicians and natural scientists, most of the speakers rejected his doctrine, including the celebrated Rudolf Virchow,[54] who was a scientist of the highest authority of his time.[55]

It has been contended [56] that Semmelweis could have had an even greater impact if he had managed to communicate his findings more effectively and avoid antagonising the medical establishment, even given the opposition from entrenched viewpoints.

[edit] Breakdown, death and oblivion

Beginning from 1861 Semmelweis suffered from various nervous complaints. He suffered from severe depression and became excessively absent minded. Paintings from 1857 to 1864 show that he aged rapidly.[57] He turned every conversation to the topic of childbed fever.

After a number of unfavorable foreign reviews of his 1861 book, Semmelweis lashed out against his critics in series of Open Letters.[58] They were addressed to various prominent European obstetricians, including Späth, Scanzoni, Siebold, and to "all obstetricians". They were full of bitterness, desperation, fury, and were "highly polemical and superlatively offensive"[59] at times denouncing his critics as irresponsible murderers[60] or ignoramuses.[61] He also called upon Siebold to arrange a meeting of German obstetricians somewhere in Germany to provide a forum for discussions on puerperal fever where he would stay "until all have been converted to his theory." [62] The attacks undermined his professional credibility.

In mid-1865, his public behaviour became irritating and embarrassing to his associates. He also began to drink immoderately; he spent progressively more time away from his family, sometimes in the company of a prostitute; and his wife noticed changes in his sexual behavior. On 13 July 1865 the Semmelweis family visited friends, and during the visit Semmelweis's behavior seemed particularly inappropriate.[63]

It is impossible to appraise the nature of Semmelweis' disorder. It may have been Alzheimer's disease, a form of senile dementia, which is associated with rapid aging.[64] It may have been third stage of syphilis, a then-common disease of obstetricians who examined thousands of women at gratis institutions.[65] Or it may have been emotional exhaustion from overwork and stress.

|

Semmelweis' Open Letter to all professors of obstetrics 1862 (original) |

|||

In 1865 János Balassa wrote a document referring Semmelweis to a mental institution. On 30 July Ferdinand von Hebra lured him, under the pretense of visiting one of Hebra's "new Institutes[66]", to a Viennese insane asylum located in Lazarettgasse[67], not far from the General Hospital — definitely not one of Vienna's best. Semmelweis surmised what was happening and tried to leave. He was severely beaten by several guards, secured in a straitjacket and confined to a darkened cell. Apart from the straitjacket, treatments at the mental institution included dousing with cold water and administering castor oil, a laxative. He died after two weeks, on 13 August 1865, aged 47, from a gangreneous wound, possibly inflicted by the beating. The autopsy revealed extensive internal injuries, the cause of death pyemia — blood poisoning. In maternity clinics this would have been called childbed fever. [68]

Semmelweis was buried in Vienna on 15 August 1865. Only a few persons attended the services. Not one family member, not one in-law, not one colleague from the University of Pest was in attendance.[69] A few medical periodicals in Vienna and Budapest included brief announcements of Semmelweis's death. The rules of the Hungarian Association of Physicians and Natural Scientists specified that a commemorative address be delivered in honor of each member who had died in the preceding year. For Semmelweis there was no address; his death was never even mentioned. [70]

János Diescher was appointed Semmelweis' successor at the Pest University maternity clinic. Immediately mortality rates jumped sixfold to six percent. But there were no inquiries and no protests; the physicians of Budapest said nothing. Almost no one — either in Vienna or in Budapest — seems to have been willing to acknowledge Semmelweis's life and work. [70]

His remains were transferred to Budapest in 1891. On 11 October 1964 they were transferred once more to a space in the garden wall of the house in which he was born. The house, in the meantime, had been converted into an historical museum and library, a monument to Ignaz Semmelweis. [71]

|

János Balassa wrote Semmelweis' referral to asylum |

Ferdinand von Hebra lured him to the asylum |

[edit] Legacy

Semmelweis' advice on chlorine washings was probably more influential than he realized himself. Many doctors, particularly in Germany, appeared quite willing to experiment with the practical handwashing measures that he proposed, but virtually everyone rejected his basic and ground-breaking theoretical innovation — that the disease had only one cause, lack of cleanliness.[72] Professor Gustav Adolf Michaelis from a maternity institution in Kiel replied positively to Semmelweis' suggestions — eventually he committed suicide, however, because he felt responsible for the death of his own cousin, whom he had examined after she gave birth.[73]

On a broader scale, to a contemporary reader, Semmelweis would appear to have demonstrated glaringly evident experimental evidence, that chlorine washings reduced childbed fever. Today, it may seem absurd that his claims were rejected, precisely on the grounds of purported lack of scientific reasoning, or what today would be called a scientific proof. It is equally absurd that his unpalatable observational evidence only became palatable when seemingly-unrelated work by Louis Pasteur in Paris some more than twenty years later suddenly offered a theoretical explanation for Semmelweis' observations — the germ theory of disease.

As such, the Semmelweis story is often used in university courses with epistemology content, e.g. philosophy of science courses — demonstrating the virtues of empiricism or positivism and providing a historical account of which types of knowledge count as scientific (and thus accepted) knowledge, and which do not. It is an irony that Semmelweis' critics considered themselves positivists. They could not accept his ideas of minuscule and largely invisible amounts of decaying organic matter as a cause of every case of childbed fever. To them, Semmelweis seemed to be reverting to the speculative theories of earlier decades that were so repugnant to his positivist contemporaries.[74] (For an example of an earlier dead-end speculative theory that had halted scientific development, see phlogiston).

Other legacies of Semmelweis continues in:

- Semmelweis is now recognized as a pioneer of antiseptic policy

- Semmelweis University, a university for medicine and health-related disciplines (located in Budapest, Hungary), is named after Semmelweis; and

- The Semmelweis Orvostörténeti Múzeum[75] (Semmelweis Medical History Museum) is located in the former home of Semmelweis.

- The Semmelweis Klinik, a hospital for women only, located in Vienna, Austria.

- In 2008 Semmelweis was selected as a main motif for the Austrian 50 euro Ignaz Semmelweis commorative coin. The obverse shows a portrait of the eminent doctor together with the rod of Asclepius.

Morton Thompson's 1949 novel The Cry and the Covenant is based on the life of Semmelweiss.

Yet a legacy is the so-called Semmelweis reflex or Semmelweis effect. It is a metaphor for a certain type of human behaviour characterized by reflex-like rejection of new knowledge because it contradicts entrenched norms, beliefs or paradigms — named after Semmelweis whose perfectly reasonable hand-washing suggestions were ridiculed and rejected by his contemporaries. There is some uncertainty about the origin and generally accepted use of the expression.

[edit] Films

- That mothers might live, USA 1938: MGM (Regie Fred Zinnemann) Oscar for the best shortfilm

- Semmelweis, Hungary 1940: Mester Film (Director André De Toth)

- Semmelweis – Retter der Mütter, GDR 1950: DEFA (Director Georg C. Klaren)

- Ignaz Semmelweis – Arzt der Frauen, Western-Germany/Austria 1987: ZDF/ORF (Director Michael Verhoeven)

- Semmelweis, the Netherlands 1994: Humanistische Omroep Stichting (Director Floor Maas)

- Docteur Semmelweis, France/Poland 1995 (Director Roger Andrieux)

- Semmelweis (shortfilm), USA/Austria 2001: Belvedere Film (Director Jim Berry)

[edit] See also

- Historical mortality rates of puerperal fever

- Contemporary reaction to Ignaz Semmelweis

- The Cry and the Covenant

- Oliver Wendell Holmes

- Joseph Lister

- Semmelweis University (Budapest)

- Semmelweis Society - a pressure group for physicians that aims to alert the public to the hazards of what it calls sham peer review.

[edit] Notes

- ^ "Ignaz Semmelweis" is pronounced, using typical German pronunciation rules, as "igg-nahts zem-mull-vice" ("w" is spoken like "v" and "s" like "z" as in Sieben, seven)

- ^ Nuland, Sherwin B.; Richard Horton (25 March 2004). "'The Fool of Pest': An Exchange". New York Review of Books 51 (5). http://www.nybooks.com/articles/17009. Retrieved on 20 February 2009.

According to Nuland, the name Semmelweis is of Swabian origin, and Semmelweis' ancestors were baptized as Roman Catholics as far back as 1670. However, Horton states that "the question of whether Semmelweis's family were Jewish or retained a strong Jewish cultural identity remains contested" and argues that the issue of Semmelweis' ethnicity is "open to debate". - ^ translated from: [er] erhielt 1806 das Bürgerrecht in Buda[clarification needed]

- ^ translated from: Spezereien- und Kolonialwarengroßhandlung[clarification needed]

- ^ Antall, József; Géza Szebellédy (1973). Aus den Jahrhunderten der Heilkunde. Budapest: Corvina Verlag. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:16

- ^ Details: On July 1, 1844 Semmelweis became Assistent aspirant (in German Aspirant Assistentarztes an der Wiener Geburtshilflichen Klinik — direct translation aspirant assistent-doctor at the Vienna maternity clinik) and on the 1st July 1846 he was appointed Assistent (In german: ordentlicher Assistentarzt). However, on Oct 20, 1846 his predecessor Dr Franz Breit (obstetrician) unexpectedly returned, and Semmelweis was again denoted to Aspirant. By March 20, 1847, Dr Breit was appointed professor in Tübingen and Semmelweis resumed the Assistentarzt position. (Benedek 1983:72).

- ^ Carter 2005:56

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):69

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):70

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):81

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):86

- ^ Semmelweis' reference to "cadaverous particles" were (in German) an der Hand klebende Cadavertheile Benedek 1983:95

- ^ Lancet 2(1855): 503. Quoted in Semmelweis (1861) p126 footnote 5. See also Historical mortality rates of puerperal fever#Contamination of midwifes' hands

- ^ See for instance Charles Delucena Meigs, in which there is a link to an original source document. Thanks also to Carter (2005):9 for bringing attention to yet this detail

- ^ Hebra, Ferdinand (1847). "Höchst wichtige Erfahrungen über die Aetiologie der an Gebäranstalten epidemischen Puerperalfieber". Zeitschrift der k.k. Gesellschaft der Ärzte zu Wien 4 (1): 242–244.

- ^ Hebra, Ferdinand (1848). "Fortsetzung der Erfahrungen über die Aetiologie der in Gebäranstalten epidemischen Puerperalfieber". Zeitschrift der k.k. Gesellschaft der Ärzte zu Wien 5: 64f.

- ^ Carter (2005) pp54-55

- ^ Charles Henry Felix Routh, On the Causes of the Endemic Puerperal Fever of Vienna, Medico-chirurgical Transactions 32(1849): 27-40. The lecture was delivered by Edward William Murphy since Routh was not a Fellow of the Royal Medical and Surgical Society. The review was in Lancet 2(1848): 642f. For a list of some other reviews, see Frank P. Murphy, "Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis (1818–1865): An Annotated Bibliography," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 20(1946), 653-707: 654f (Quoted from Semmelweis 1861 p175, translator Carter's footnote 8)

- ^ Wieger, Friedrich (1849). "Des moyens prophylactiques mis en usage au grand hôpital de Vienne contre l'apparition de la fièvre puerpérale". Gazette médicale de Strasbourg 9: ): 99–105.

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:10-12 (the foreword)

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:31 (the foreword)

- ^ Carter (2005) p56

- ^ Robert Reid, Microbes and Men, 1975 pp 37

- ^ Carter (2005) p57

- ^ Carter (2005) p59

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):61. See also ibid:105, that his collegue in the second clinic Franz Zipfl was granted a two year extension, as was eventually Braun himself

- ^ Carter (2005) p61

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:105

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:52

- ^ Carter (2005) p67

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):107

- ^ Carter (2005):68

- ^ Semmelweis (1861):106-108

- ^ a b c Carter (2005):69

- ^ footnote 73 by translator Carter in Semmelweis (1861) p24

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:56

- ^ They had five children. A son died shortly after birth, and a daughter died at 4 months. Another son committed suicide at age 23, possibly due to gambling debts. One daughter remained unmarried, and another had children of her own.Carter (2005):70

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:174

- ^ Semmelweis (1861) Translator Carter's footnote 12 p 176. The British quote is from "Puerperal Fever," Lancet 2(1856), 503-05: 504; also the translator's note

- ^ Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift 6 (1856) 536, quoted in Semmelweis (1861) p24

- ^ The time to stop the nonsense of hand washing with chlorine translation is e.g. found in the Semmelweis entry of Encyclopedia Britannica 2004 ed.

- ^ The page in question (page 536 of the Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift 6, 1856) is accessible on the Internet [1] (access 11 May 2008). Actual quote is "'Wir glaubten diese Chlorwaschungs-Theorie habe sich längst überlebt; die Erfahrungen und statistichen Ausweisse der meisten geburtshilflichen Anstalten protestieren gegen ubige Anschanung; es wäre an der Zeit sich von dieser Theorie nicht weiter irreführen zu lassen. D. Red." [D. Red. = Der Redacteur]. Irreführen means to misguide, deceive or mislead — there is little support for the nonsense English translation.

- ^ The report was "A gyermekágyi láz kóroktana" The Etiology of Childbed Fever published in Orvosi hetilap 2(1858); a translation into German is included in Tiberius von Györy, Semmelweis' gesammelte Werke (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1905), pp. 61-83. This was Semmelweis's first publication on the subject of puerperal fever. According to Győry the substance of the report was contained in lectures delivered before the Budapester königliche Ârzteverein in the spring of 1858. Ibid.. p. 601. Quoted in Semmelweis (1861) p112 translator Carter's footnote 21

- ^ Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis, "A gyermekágyi láz fölötti véleménykülönbség köztem s az angol orvosok közt," Orvosi hetilap 4 (1860), 849-51, 873-76, 889-93, 913-15. (Semmelweis 1861:24 note 75)

- ^ A work by Heinrich Silberschmidt, Historisch-kritische Darstellung der Pathologie des Kindbettfiebers von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die unserige,published 1859 in Erlangen, which only mentions Semmelweis incidentally and without dealing with the transfer of toxic materials by the hands of physicians and midwives whatsoever. The book was awarded a prize by the medical faculty of Würzburg at the instigation of Friedrich Wilhelm Scanzoni von Lichtenfels ref, Hauzman, Erik E (2006). "Semmelweis and his German contemporaries" (DOC). 40th International Congress on the History of Medicine, ISHM 2006. Retrieved on 2008-06-05., see also Semmelweis (1861):212 note 48

- ^ Semmelweis (1861) p169

- ^ Schmidt, Joseph Hermann (1850). "Die geburtshülfliche-klinischen Institute der königlichen Charité". Annalen des charité-Krankenhauses zu Berlin 1: 485–523: 501. quoted in Semmelweis (1861) p34

- ^ Carl Braun's thirty causes appear in his Lehrbuch der Geburtshülfe (Vienna: Braumüller, 1857), p. 914. In the first of these, published in 1855, he mentions Semmelweis in connection with his discussion of cause number 28, cadaverous poisoning. In the later version, however, although he discusses the same cause in the same terms, all references to Semmelweis have been dropped. (Note by translator Carter in footnote 105 p34 in Semmelweis (1861)

- ^ footnote 73 by translator Carter in Semmelweis (1861) p24

- ^ The review appeared in Breisky, August (1861). Vierteljahrschrift fur die praktische Heilkunde 18 Literarischer Anzeiger 2: 1–13: 501.. The remarks quoted above appear on p. 1. Quoted in Semmelweis (1861) p41

- ^ Levy, Karl Edouard Marius (1848). "De nyeste Forsög i Födselsstiftelsen i Wien til Oplysning om Barselfeberens Aetiologie". Hospitals-Meddelelser 1: 199–211. (alternative spelling Carl Edvard Marius Levy) quoted in Semmelweis (1861) p180-181

- ^ Note by Carter (translator) footnote 17 in Semmelweis (1861) p183

- ^ "Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis - Britannica Concise" (history), Imre Zoltán, Britannica Concise, 2006, webpage: CBrit-Semmelweis: birthname, doctorate 1844, objections of superiors, mortality 18.27 to 1.27 percent, fired for politics of 1848 rebellion, his 1861 book Die Ätiologie, pathologist Rudolf Virchow rejected his doctrine.

- ^ Rudolf Virchow, professor of pathological anatomy, a scientist of the highest authority of his age. His father-in-law was the president of the Obstetrical Society of Berlin, and he was known for being in good relationship with Franz Kiwisch von Rotterau. Virchow’s great authority in medical circles potently contributed to the lack of recognition of the Semmelweis doctrine for a long time. Hauzman, Erik E (2006). "Semmelweis and his German contemporaries" (DOC). 40th International Congress on the History of Medicine, ISHM 2006. Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ^ e.g. by Nuland, Sherwin B. (2003). The Doctors' Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever and the Strange Story of Ignac Semmelweis. W W Norton & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-393-05299-0.

- ^ Senmmelweis 1861:57

- ^ The 1862 open letter is available at Austrian literature online, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek [2]. He repeatedly lashes out against Carl Braun (obstetrician) and Friedrich Wilhelm Scanzoni von Lichtenfels

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:57

- ^ Carter 2005:73

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:41

- ^ Hauzman, Erik E (2006). "Semmelweis and his German contemporaries" (DOC). 40th International Congress on the History of Medicine, ISHM 2006. Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ^ Carter 2005:74

- ^ Sherwin B. Nuland p270

- ^ Carter 2005

- ^ Benedek 1983:293

- ^ Landes-Irren-anstalt in die Lazarettgasse. (Benedek 1983:293

- ^ Carter 2005:76-78

- ^ Carter 2005:78

- ^ a b Carter 2005:79

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:58

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:48

- ^ Semmmelwies 1861:176-178

- ^ Semmelweis 1861:43

- ^ Semmelweis Orvostörténeti Múzeum — Home Page

[edit] References

- Benedek, István (1983). Ignaz Phillip Semmelweis 1818–1865. Druckerei Kner, Gyomaendrőd, Hungary: Corvina Kiadó (Translated from Hungarian to German by Brigitte Engel). ISBN 9631314596.

- William Broad and Nicholas Wade, Betrayers of the Truth: Fraud and Deceit in the Halls of Science, Simon and Schuster, NY; 1982.

- Carter, K. Codell; Barbara R. Carter (February 1, 2005). Childbed fever. A scientific biography of Ignaz Semmelweis. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1412804677.

- Louis-Ferdinand Celine, "Semmelweis",Gallimard, 1977.

- Semmelweis, Ignaz; K. Codell Carter (translator and extensive foreword) (1861). Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. University of Wisconsin Press, September 15, 1983. ISBN 0299093646.

- Nuland, Sherwin B, The Doctors' Plague: Germs, Childbed Fever, and the Strange Story of Ignác Semmelweis, 2003.

[edit] External links

- Sloan Science and Film / Short Films / Semmelweis by Jim Berry 17 minutes

- Extracts from Semmelweis' 1861 book, The Etiology, Concept, and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever were published in the January 2008 edition of Social Medicine

- BMJ: Ignaz Semmelweis

- Catholic Encyclopedia entry

- "Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis". John H. Lienhard. The Engines of Our Ingenuity. NPR. KUHF-FM Houston. 1991. No. 622. Transcript.

- Who Named it? Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis

- Tan S Y and Brown J Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis

- Caroline M De Costa, The contagiousness of childbed fever : a short history of puerperal sepsis and its treatment, eMJA The Medical Journal of Australia, MJA 2002 177 (11/12): 668-671

- review, The Fool of Pest, The New York Review of Books, 51:3 (February 26, 2004)

- The Semmelweis Society an organization dedicated to protecting physicians from sham peer review, named for Ignaz Semmelweis.

- Semmelweis's first post-stamp, Hungary, 1932