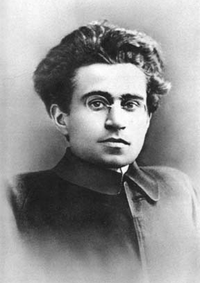

Antonio Gramsci

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article includes a list of references or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (March 2008) |

| Western Philosophy 20th-century philosophy |

|

Antonio Gramsci |

|

| Full name | Antonio Gramsci |

|---|---|

| School/tradition | Marxism |

| Main interests | Politics, Ideology, Culture |

| Notable ideas | Hegemony, Organic Intellectual, War of Position |

|

Influenced by

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Antonio Gramsci (IPA: ['ɡramʃi]) (22 January 1891–27 April 1937) is the Italian political leader and theoretician who co-founded the Partito Comunista d’Italia (PCI — Communist Party of Italy) in 1921, and was its leader in the Italian Parliament, in 1924. When the Fascist régime outlawed the PCI in 1926, they arrested and imprisoned him from 1926 until 1937. In the Marxist philosophic tradition, his writings — analyses of culture and political leadership — are intellectually most original; he is best known for the concept of cultural hegemony — whereby, the ruling class of a capitalist society coerce the working class to adopt its values in maintaining the State. [1]

Contents |

[edit] Life

| Part of a series on |

| Marxist theory |

|

|

People

|

|

Criticism

|

|

Categories

|

[edit] At Sardinia

Antonio Gramsci was born in Ales, Sardinia, Italy, in 1891, the fourth of seven sons of Francesco Gramsci, a man of the Arbëreshë ethnic Albanian minority of Italy; the surname Gramsci derives from Gramsh, a small town in Albania. Mr Gramsci was a minor public official whose corruption forced his family to itinerant residence in several Sardinian villages, settling, eventually, in Ghilarza. In 1898, he was jailed for embezzlement, thus, obliging seven-year-old Antonio to quit school and work casual jobs to support the impoverished family until his father’s release in 1904, six years later. He suffered a childhood accident that left him hunch-backed and physically stunted, thus, suffering life-long ill health. [2] In the event, he completed secondary school in Cagliari, where he lived with elder brother, Gennaro, an ex-soldier become militant socialist. In that time, Antonio Gramsci’s political sympathies lay not with Socialism, but with the Sardinian peasants and miners who perceived their poverty as consequence of the socio-economic privileges of the industrialised northern Italy, politically turning them to Sardinian nationalism in response.

[edit] At Turin

In 1911, Antonio Gramsci won a scholarship to the University of Turin , where he read literature, and studied linguistics under Matteo Bartoli, (also sitting the examination was future comrade Palmiro Togliatti). The city of Turin then was becoming industrialised; the Fiat and Lancia automobile companies were recruiting workers from Italy’s poor regions; Gramsci helped them organise trade unions; his world-view thus shaped, he joined the Partito Socialista Italiano (PSI — Italian Socialist Party) in 1913.

Despite his academic ability, poverty, ill-health, and political commitment, led to abandoning school in 1915, but, with a formidable knowledge of history and philosophy. At university, he encountered the thought of Antonio Labriola, Rodolfo Mondolfo, Giovanni Gentile, and Benedetto Croce whose Hegelian Marxism Labriola denoted the “Philosophy of Praxis” [3] — a philosophy of action about which he was ambiguous — despite later using it to outwit Fascist censors whilst a political prisoner.

Beginning in 1914, his articulate writing, commentary, and political theorising in socialist newspapers (e.g. Il Grido del Popolo) established him as a journalist of high intellectual repute. In 1916, he was co-editor of the Piedmont edition of the Avanti! (Forward) newspaper (the PSI’s official organ) and simultaneously worked at educating and politically organising the city’s workers; his first public speeches were about the writer Romain Rolland, the French Revolution, the Paris Commune, and the emancipation of women. After the Fascists arrested the PSI’s leaders, because of the August 1917 revolutionary riots, he was elected to the Party’s Provisional Committee, and editor of Il Grido del Popolo.

In April of 1919, he, Palmiro Togliatti, Angelo Tasca, and Umberto Terracini founded the weekly newspaper L’Ordine Nuovo (The New Order). In October, despite hostile, factional divisions, the PSI joined the Third International (1919–1943 aka the Comintern). To wit, on perceiving that L’Ordine Nuovo as ideologically closest to the Bolsheviks, Vladimir Lenin supported Gramsci’s faction against Amadeo Bordiga’s extreme-Left, anti-parliamentary faction — because Gramsci advocated workers’ councils, spontaneously organised in the Biennio rosso (Red Biennium, 1918–20) labour and agricultural strikes, as the workers’ effective means for controlling production. Despite believing he concorded with Lenin’s policy of “All power to the Soviets”, Bordiga attacked Gramsci for betraying syndicalism, (see Georges Sorel, Daniel DeLeon), and, at the workers’ defeat, in spring of 1920, Gramsci was almost alone in defending the councils.

[edit] The Partito Comunista d’Italia

When the workers’ councils failed to become a national political movement, Gramsci decided upon a vanguard Leninist Communist Party to lead them. The men of L’Ordine Nuovo thought the centrist PSI timid, and allied themselves with Bordiga’s faction, and founded the PCI — the Partito Comunista d’Italia (Communist Party of Italy) on 21 January 1921, at Livorno; and, against Bordiga, he supported the anti-Fascist Arditi del Popolo (People’s Squads, established June 1921) to fight the paramilitary Squadre d’Azione (Action Squads) aka the Blackshirts, [4] who made feasible the violent ascent to power of the PNF — the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party, established 1921) lead by Benito Mussolini. [5] Despite being a PCI co-founder, Gramsci was subordinate to Bordiga, who dominated it, and its programme, with emphatic discipline, central command, and ideologic purity — until losing its leadership in 1924.

In 1922, Gramsci represented the PCI at the Third International, in Russia; there, he met, and later married, the violinist Julia Schucht, with whom he had two sons. [6] His mission to Moscow coincided with Fascism’s Italian ascent; he then returned with orders fostering (despite the PCI’s leaders) a united Leftist front against Fascism. Ideally, the PCI would have been the front’s centre (and Moscow’s control of the Italian Left) but, the PSI traditionally held said leadership, and opposed the Communist Pary of Italy as too radical and too young.

In late 1922 and early 1923, the Mussolini suppressed every opposition party, arresting most of the PCI’s leaders, including Bordiga; in late 1923, Moscow sent Gramsci to Vienna to revive the PCI, then torn with internecine strife. In 1924, as the leader, he was elected Deputy for the Veneto, organising and launching L'Unità (Unity), the PCI’s official newspaper. In January 1926, at the Lyons Congress, the PCI adopted his programme for a united front restoring Italian democracy.

In 1926 Joseph Stalin’s manœuvring in the Bolshevik Party prompted Gramsci to write to the Comintern, deploring Leon Trotsky’s opposition and his faults, however, in Moscow, PCI representative Palmiro Togliatti read Gramsci’s anti-Trotsky letter, and did not deliver it; that became a never-resolved political conflict between them.

[edit] Political imprisonment and death

On 9 November 1926, using an attempted assassination of Mussolini (occurred days earlier), the Fascist Government effected “emergency” laws to suppress its political enemies; Gramsci was jailed in the Regina Cœli (Queen of Heaven) prison — despite his parliamentary immunity as PCI leader. At trial, the prosecutor said: “For twenty years, we must stop this brain from functioning”; [7] the Court sentenced him to five years’ confinement at Ustica island, north of Sicily; the next year, he was re-sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment at Turi, near Bari.

The isolation and meagre medical attention, aggravated his normally poor health to continual decline. In 1932, the USSR and Fascist Italy failed at exchanging political prisoners, Gramsci included. Two years later, in 1934, because of his much deteriorated health, the Fascists granted him conditional freedom, after hospitalisations at Civitavecchia, Formia, and Rome. To wit, on 27 April 1937, the forty-six-year-old Antonio Gramsci died in Rome, shortly upon release from political prison, and was buried in the Roman Protestant Cemetery.

Adding Papist insult to Fascist injury, Archbishop Luigi de Magistris, of the Apostolic Penitentiary of the Holy See, claimed that the Marxist intellectual Antonio Gramsci: “Returned to the faith of his infancy [. . .] and died taking the sacraments” (cf. Julian the Apostate); [8] nevertheless, Italian State documents do not record that the Communist leader requested a priest, like-wise, witness accounts of Gramsci’s death do not record either a death-bed conversion to Roman Catholicism or his reneging of Socialist principles. [9]

[edit] Political and philosophic thought

Antonio Gramsci is an important twentieth-century intellectual, and a key theoretician of Western Marxism, second to Karl Marx, himself. [10] This reputation derives from the Lettere del carcere (Letters from Prison), published as the Prison Notebooks (1947), [11] [12] written (1929–1935) during eleven years of Fascist incarceration; they derive from some 30 notebooks and 3,000 pages of historical analyses — delineating Italian history and nationalism, Marxist theory, critical theory, and educational theory — thematically comprehended in and as:

- Cultural hegemony — the ruling class’s spiritual and cultural dominance (rule) of the working class in maintaining the capitalist state.

- The need for educating workers to develop intellectuals from the working class.

- The distinction, between the direct domination of political society (law, police, Church, et al.) and the indirect domination of civil society (family, schools, trade unions, et al.) whose leadership is constituted via ideologic consent.

- Absolute historicism.

- The critique of economic determinism.

- The critique of philosophical materialism.

[edit] Cultural hegemony

Marxists, such as V.I. Lenin, applied the concepts of political hegemony (indirect imperial rule) to establish the imperative need for the Working Class’s leadership of a democratic revolution. In turn, Antonio Gramsci sociologically developed hegemony into cultural hegemony (a class’s domination of a society by imposing its values) acutely explaining why orthodox Marxism’s “inevitable” socialist revolution had yet to occur in the early twentieth century.

To maintain the societal status quo and thwart revolution from below, Capitalism developed a “consensus culture”, wherein, the working class (proletariat) identified their best interests with the best interests of the (ruling class) bourgeoisie; besides force (arms) and power (coercion), Capitalism retains control via the hegemonic culture determining the substance of the social institutions (press, radio, Churches, labour unions, et al.) who propagate the ruling class’s ideology (values, myths, beliefs) that the working class accept-adopt as their own “common sense” view — the world as it is and should be. [13] [14]

To defend themselves against cultural hegemony from above, the proletariat must create their own, discrete culture to dispel the belief that bourgeois ideology is “natural” and “normal” for the entire society; the proletariat then would attract the support of the intelligentsia. Despite Lenin positing that culture is ancillary to political objectives, for Gramsci, attaining political power requires cultural hegemony; for a class to establish societal leadership (intellectual and moral) in modern conditions, they must transcend their own, narrow interests (economic and corporate) with an historic bloc of alliances (political compromises) with the other socio-economic classes, in order to produce and reproduce the nexus of social relations, institutions, and ideology required for leadership; thus, the importance of the superstructure in maintaining and fracturing the relations that are the foundational base of society. (see George Sorel)

Western bourgeois ideology (values, myths, beliefs) derives from religion, therefore, the polemic against hegemonic culture is against supernatural ideology; nevertheless, Gramsci was impressed with Roman Catholicism’s power over the popular mind, and the Church’s carefully preventing an excessively-wide gap between religion for the educated and religion for the uneducated. To wit, Marxism must marry Renaissance Humanism’s intellectual critique of religion to the Protestant Reformation elements that appeal to the mass populace — hence, Marxism will supersede religion only when it meets the spiritual needs of people, expressed as their experience of life; yet, ultimately, hegemonic dominance relies upon power (coercion), and, when power fails (a crisis of authority), cultural hegemony’s masks of consent fall off, and Capitalism resorts to naked, merciless force (arms) to control its working classes.

[edit] Intellectuals and education

Every man is intellectual (possessed of intellect and reason), yet, each man does not function in society as “an intellectual”. Modern intellectuals are the organisers, directors, and builders of society, who produce cultural hegemony with ideologic apparatuses (education, mass media, et cetera), and, there is a distinction between the traditional intelligentsia who (incorrectly) perceive themselves as apart from society, and the thinker intelligentsia, organic to each social class, who articulate the experiences (thoughts and feelings) that the (uneducated) mass populace are unable to express for themselves.

Creating a proletarian culture requires the type of education needed for developing organic, working-class intellectuals who will present Marxist ideology to the proletariat, from within the proletariat, in order to renovate and criticise the status quo for the mass populace. These educational ideas correspond to the theory and practice of critical pedagogy and popular education exemplified in the work of Paulo Freire and Frantz Fanon, and others; Antonio Gramsci is the intellectual mentor of contemporary adult and popular education.

[edit] The State and Civil society

Cultural hegemony derives from Gramsci’s concept of the capitalist State that rules with force (arms) and power (coerced consent). The State is not merely “the Government”, but a dualistic polity — the political society (social institutions) and the civil society (the private realm and the economy); the former operates via force, the latter via power, yet, the division is intellectual, not literal, as both societies constitute the State.

In modern Capitalism, the bourgeoisie maintain economic control of civil society with “passive revolution” permitting that some socio-economic demands (of labour unions, political parties, et al.) be met in the political sphere, momentarily transcending its immediate economic interests, to permit limited change to their cultural hegemony over the workers; examples are reformism, Fascism, Scientific Management, and the assembly line methods of Frederick Winslow Taylor and Henry Ford.

Drawing from Niccolò Machiavelli, Gramsci posits the revolutionary political party as “The Modern Prince” who will help the working class(es) develop organic intellectuals and a concomitant, proletarian cultural hegemony in civil society — whose complex nature permits first the “War of Position” (culture war), to undermine the ruling class’s cultural hegemony, then the “War of Manœvre” (armed insurrection) to establish a socialist society; the example is the Russian proletariat’s storming of the Winter Palace in the October Revolution of 1917; yet, Gramsci rejects the State-worship resultant from identifying political society with civil society, as did the Jacobins and the Fascists. The proletariat must create a self-regulating society that, then, will permit the withering away of the state upon achieving world communism.

[edit] Historicism

Like Karl Marx in his early work, Antonio Gramsci is a proponent of historicism (historical laws), wherein, “meaning” derives from the relations among practical activities (praxis) and the “objective” social processes of history — to which praxis fits. Ideas have no meaning without context (socio-historic circumstance), i.e. apart from their practical function and origin. The intellectual concepts that organise knowledge of the world do not (primarily) derive meaning from the relations among people and things, but derive their meaning(s) from the social relations among the users of the concepts; resultantly, human nature is not an immutable idea, but an idea whose (mutable) meaning varies with its historical context, moreover, philosophy and science do not reflect a reality independent of the mind, but are factually “true” in that they express the material developments their time.

Material truth is real, regardless of time and place, and scientific knowledge (including Marxism) accumulates historically — as accumulated material truth; thus, Marxism is “true”, because it is physical, material science, not metaphysical belief. Philosophically and pragmatically, Marxism is “true” because it more accurately articulates the proletariat’s class consciousness (the material truth of its time) than do other, like theories. This anti-scientistic and anti-positivist perspective derives from the idealist-æsthetic work of philosopher Benedetto Croce, yet, Gramsci’s “absolute historicism” departs from the idealist (Hegelian) tenor of Croce’s thought (the metaphysical synthesis of “historical destiny”); Gramsci repudiated that characterisation when his account of history is criticised as relativism.

[edit] Critique of economism

The article “The Revolution against Das Kapital” proposes that the Russian October Revolution invalidated the idea that Socialist revolution must await the full development of the capitalist forces of production. As Marxism is not determinist, the principle of the “causal primacy” of the forces of production is a philosophic misconception — economic and cultural changes are expressions of basic, historical processes; which is primary remains indeterminate.

The fatalistic belief political triumph was inevitable, because of “historical laws”, was common to the workers’ movement in its early years. That fatalistic belief was product of the historical circumstance of an oppressed socio-economic class that was mostly restricted to defensive action; it was an intellectual hindrance to be discarded when the workers assumed the political initiative. As a philosophy of praxis (action), Marxism cannot rely upon imperceptible “historical laws” as agents of social change; human praxis defines history, therefore, it includes the human will, yet, the will to power cannot achieve anything men want in a given context, because, when the proletariat’s political consciousness develops to the action stage, it will encounter historical circumstances that cannot be arbitrarily altered; “historical inevitability” does not determine the possible results of political action.

The critique of economism comprehends the economic determinism practiced by Italian trade union syndicalists; most settled for a reformist, gradualist approach, by refusing to struggle politically and economically. Although Gramsci viewed trade unions as a counter-hegemonic force in capitalist society, the leaders merely saw the unions as means to improve conditions within the extant political structure — which he defined as “vulgar economism”, merely covert reformism and liberalism.

[edit] Critique of Materialism

That history and collective praxis determine whether or not a philosophic question has meaning, Gramsci’s views contradict Engels’s and Lenin’s metaphysical materialism and “copy” theory of perception. Marxism does not deal with a reality independent of the mind and experience, thus, the concept of an objective universe beyond history and praxis is analogous to believing in a supernatural god — because there is no objectivity, only the universal intersubjectivity to be established in a future Communist society, so, natural history has meaning only in relation to human history. Like primitive common sense, philosophic materialism results from uncritical thought, and could not, as Lenin said, be opposed to religious superstition. [15]

Despite that, Gramsci accepts the existence of a cruder Marxism; the proletariat as a dependent class meant that Marxism, as a philosophy, often could only be expressed as popular superstition and common sense; nonetheless, it is necessary to challenge the ideologies (values, myths, beliefs) of the educated classes, and, in doing so, Marxists must present their philosophy in sophisticated guise, and attempt to genuinely understand the views of their opponents.

[edit] Gramsci’s intellectual influence

Although his thought originates from the organized Left, Antonio Gramsci is important in contemporary cultural studies and critical theory. Centrist and right-wing theorists derive insights from his concepts, e.g. cultural hegemony; Neo-gramscianism is prevalent in neoliberal theory. Moreover, his influence upon discourse about popular culture and popular culture studies contains potential political and ideologic resistance to the dominant government and business interests.

Critics accuse him with fostering power struggles with ideas, because his analytic methods, reflected in current academic controversy, counter liberal, open-ended inquiry based on “apolitical” readings of the Western Classics. Given that he was not an teacher — but an intellectual deeply engaged with Italian culture, history, and liberal thought — it is an ironically odd, historical turn to credit and blame him for the controversies in contemporary academic politics.

His socialist legacy is disputed; Palmiro Togliatti, who led the PCI (renamed the Italian Communist Party) after World War II, and whose gradualist approach presaged Eurocommunism, said that the PCI’s practices, in that time, concorded with Gramsci’s thought; others counter that Antonio Gramsci was a Left Communist, who, likely, would have been purged from the Communist Party of Italy had Fascist imprisonment not prevented regular communication with Moscow under Joseph Stalin’s tenure.

[edit] Influences on Gramsci’s thought

- Niccolò Machiavelli — the 16th-century Italian political scientist’s theory of the State.

- Karl Marx — philosopher, historian, economist, and founder of Marxism.

- Antonio Labriola — the first, notable Italian Marxist theorist, believed Marxism’s principal feature was its history–philosophy nexus.

- Georges Sorel — French syndicalist who rejected the “inevitability” of historical progress.

- Vilfredo Pareto — Italian economist and sociologist; for his theory of interaction between the mass populace and the élite(s).

- Henri Bergson — French philosopher.

- Benedetto Croce — liberal anti-Marxist and idealist philosopher whose thought Gramsci carefully and thoroughly critiqued.

[edit] Thinkers whom Gramsci influenced

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2008) |

- Zackie Achmat

- Louis Althusser[16]

- Perry Anderson

- Michael Apple

- Giovanni Arrighi

- Zygmunt Bauman

- Homi K. Bhabha

- Gordon Brown[17]

- Judith Butler

- Noam Chomsky

- Robert W. Cox

- Alain de Benoist

- John Fiske

- Michel Foucault

- Paulo Freire

- Hugo Costa

- Eugene D. Genovese

- Stephen Gill[18]

- Paul Gottfried

- Stuart Hall

- Michael Hardt

- David Harvey

- Hamish Henderson

- Eric Hobsbawm

- Samuel P. Huntington

- Bob Jessop

- Ernesto Laclau

- Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos

- Marilena Chauí

- Chantal Mouffe

- Antonio Negri

- Luigi Nono

- Michael Omi

- Pier Paolo Pasolini

- Nicos Poulantzas

- William I Robinson

- Edward Said[19]

- Ato Sekyi-Otu

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

- E.P. Thompson

- Cornel West

- Howard Winant

- Raymond Williams

- Eric Wolf

- Howard Zinn

- Eqbal Ahmad[20]

[edit] Gramsci’s pop culture influence

Music:

- Gramsci Melodic — US (Pittsburgh) synthpop band

- Scritti Politti — Scots alternative band

[edit] See also

- Reformism

- Superstructure

- Articulation (sociology)

- Risorgimento

- Praxis School

- Liberation theology

- Abahlali baseMjondolo

- Treatment Action Campaign

[edit] Endnotes

- ^ Cambridge Biographical Encyclopedia, Second Edition, (1998), p.391

- ^ Duncan Townson, The New Penguin Dictionary of Modern History: 1789–1943 (1994), p. 327

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Second Edition, (2005) p.751

- ^ Duncan Townson, The New Penguin Dictionary of Modern History: 1789–1945 (1994), p. 84

- ^ Chambers Dictionary of World History (2000), p. 280

- ^ Picture of the Gramsci’s and their two sons in the Italian-language Antonio Gramsci Website.

- ^ Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (1971), ISBN 0-85315-280-2, p. xxxix.

- ^ [1] Times Online

- ^ [2] National Catholic Reporter

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition, (1993), p. 1,119

- ^ Cambridge Biographical Encyclopedia, Second Edition, (1998), p.391

- ^ Duncan Townson, The New Penguin Dictionary of Modern History: 1789–1945, pp. 327–28

- ^ Ross hassig, Mexico and the Spanish Conquest (1994), pp. 22–3

- ^ Duncan Townson, The New Penguin Dictionary of Modern History: 1789–1945, pp. 328

- ^ Lenin: Materialism and Empirio-Criticism.

- '^ Althusser, Louis ((1977)) [(1971)]. "“Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses”" (in English). Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays. Ben Brewster, translator (2nd ed.). London: New Left Books. pp. 136n. ISBN 902308-89-0. http://www.marx2mao.com/Other/LPOE70ii.html. Retrieved on 27/09/08. "“To my knowledge Gramsci is the only one who went any distance in the road I am taking”."

- ^ “In The Red Paper of Scotland in 1975, Gordon Brown outlined his vision. So, what changed?” — Neal Ascherson, “Life on the ante-eurodiluvian Left”, The Observer, 5 November 2000.

- ^ Stephen Gill, York University, was influenced by Gramsci and Cox in writing Power and Resistance in the New World Order, Palgrave Macmillan (2002); Gramsci, Historical Materialism and International Relations, Cambridge University Press (1993); American Hegemony and the Trilateral Commission, Cambridge University Press (1991).

- ^ Said, Edward W. (2003) [(1978)]. "Introduction" (in English). Orientalism. London: Penguin Books. pp. 7. "“In any society not totalitarian, then, certain cultural forms predominate over others, just as certain ideas are more influential than others; the form of this cultural leadership is what Gramsci has identified as hegemony, an indispensable concept for any understanding of cultural life in the industrial West″."

- ^ Barsamian, David, Eqbal Ahmad: Confronting Empire (2000) South End Press. pp xxvii.

[edit] Sources

- Boggs, Carl (1984). The Two Revolutions: Gramsci and the Dilemmas of Western Marxism. London: South End Press. ISBN 0896082261.

- Bottomore, Tom (1992). The Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0631180826.

- Gramsci, Antonio (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers. ISBN 071780397X.

- Jay, Martin (1986). Marxism and Totality: The Adventures of a Concept from Lukacs to Habermas. University of California Press. ISBN 0520057422.

- Joll, James (1977). Antonio Gramsci. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0670129429.

- Kolakowski, Leszek (1981). Main Currents of Marxism, Vol. III: The Breakdown. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192851098.

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Antonio Gramsci |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Antonio Gramsci |

- Gramsci's writings at MIA

- The International Gramsci Society

- "Notes on Language". TELOS 59 (Spring 1984). New York: Telos Press

- Fondazione Instituto Gramsci

- Special issue of International Socialism journal with a collection on Gramsci's legacy

- Roberto Robaina: Gramsci and revolution: a necessary clarification

- Dan Jakopovich: Revolution and the Party in Gramsci's Thought: A Modern Application

- Gramsci’s contributions to adult and popular education

- The life and work of Antonio Gramsci

- Rare: a picture at the age of 15

- Gramsci's wife and sons

- The Praxis Prism – The Epistemology of Antonio Gramsci

- Audio and video resources on Gramsci

- Gramsci Links Archive

- Gramsci e o Brasil

- Counterhegemonic Blogspot

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Amadeo Bordiga |

Secretary of the Italian Communist Party 1924–1926 |

Succeeded by Palmiro Togliatti |

|

|||||