Mirror neuron

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

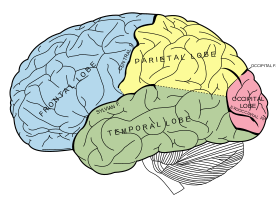

A mirror neuron is a neuron which fires both when an animal acts and when the animal observes the same action performed by another animal (especially by another animal of the same species).[1] Thus, the neuron "mirrors" the behavior of another animal, as though the observer were itself acting. These neurons have been directly observed in primates, and are believed to exist in humans and other species including birds. In humans, brain activity consistent with mirror neurons has been found in the premotor cortex and the inferior parietal cortex.

Some scientists consider mirror neurons one of the most important findings of neuroscience in the last decade. Among them is V.S. Ramachandran,[2] who believes they might be very important in imitation and language acquisition. However, despite the popularity of this field, to date no plausible neural or computational models have been put forward to describe how mirror neuron activity supports cognitive functions such as imitation.[3]

The function of the mirror system is a subject of much speculation. Many researchers in cognitive neuroscience and cognitive psychology consider that this system provides the physiological mechanism for the perception action coupling (see the common coding theory). These mirror neurons may be important for understanding the actions of other people, and for learning new skills by imitation. Some researchers also speculate that mirror systems may simulate observed actions, and thus contribute to theory of mind skills,[4][5] while others relate mirror neurons to language abilities.[6] It has also been proposed that problems with the mirror system may underlie cognitive disorders, particularly autism.[7][8] However the connection between mirror neuron dysfunction and autism remains speculative and it is unlikely that mirror neurons are related to many of the important characteristics of autism.[3]

Contents |

[edit] Discovery

In the 1980s and 1990s, Giacomo Rizzolatti was working with Giuseppe Di Pellegrino, Luciano Fadiga, Leonardo Fogassi, and Vittorio Gallese at the university of Parma, Italy. These neurophysiologists had placed electrodes in the ventral premotor cortex of the macaque monkey to study neurons specialized for the control of hand and mouth actions; for example, taking hold of an object and manipulating it. During each experiment, they recorded from a single neuron in the monkey's brain while the monkey was allowed to reach for pieces of food, so the researchers could measure the neuron's response to certain movements.[9][10] They found that some of the neurons they recorded from would respond when the monkey saw a person pick up a piece of food as well as when the monkey picked up the food. A few years later, the same group published another empirical paper and discussed the role of the mirror neuron system in action recognition, and proposed that the human Broca’s region was the homologue region of the monkey ventral premotor cortex.[11] Further experiments confirmed that approximately 10% of neurons in the monkey inferior frontal and inferior parietal cortex have 'mirror' properties and give similar responses to performed hand actions and observed actions. More recently Christian Keysers and colleagues have shown that both in humans and monkeys, the mirror system also responds to the sound of actions.[12][13] Reports on mirror neurons have been widely published[14] and confirmed[15] with mirror neurons found in both inferior frontal and inferior parietal regions of the brain. Recently, evidence from functional neuroimaging (e.g., fMRI, TMS and EEG) and behavioral strongly suggest the presence of similar mirror neurons systems in humans, where brain regions which respond during both action and the observation of action have been identified. Not surprisingly, these brain regions closely match those found in the macaque monkey.[16]

[edit] In monkeys

The only animal in which mirror neurons have been studied individually is the macaque monkey. In these monkeys, mirror neurons are found in the inferior frontal gyrus (region F5) and the inferior parietal lobule.[17]

Mirror neurons are believed to mediate the understanding of other animals' behavior. For example, a mirror neuron which fires when the monkey rips a piece of paper would also fire when the monkey sees a person rip paper, or hears paper ripping (without visual cues). These properties have led researchers to believe that mirror neurons encode abstract concepts of actions like 'ripping paper', whether the action is performed by the monkey or another animal.[18]

The function of mirror neurons in macaques is not known. Adult macaques do not seem to learn by imitation. Recent experiments suggest that infant macaqes can imitate a human's face movements, though only as neonates and during a limited temporal window.[19] However, it is not known if mirror neurons underlie this behaviour.

In adult monkeys, mirror neurons may enable the monkey to understand what another monkey is doing, or to recognise the other monkey's action.[20]

[edit] In humans

It is not normally possible to study single neurons in the human brain, so scientists cannot be certain that humans have mirror neurons. However, the results of brain imaging experiments using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have shown that the human inferior frontal cortex and superior parietal lobe is active when the person performs an action and also when the person sees another individual performing an action. It has been suggested that these brain regions contain mirror neurons, and they have been defined as the human mirror neuron system.[21]. However, a recent study shows that the signal measured by fMRI from human 'mirror neuron regions' is not necessarily generated by true mirror neurons (that is, individual neurons which respond only to the same action in self and other) [22]. For this reason, research in humans focuses on the "mirror neuron system" rather than "mirror neurons".

Several indirect measures have been used to study the mirror neuron system in humans. For example, when a person observes another person's action, his motor cortex becomes more excitable.[23] This excitability can be measured by recording the size of a motor evoked potential (MEP) induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation. The changes in MEP size are taken as a measure of mirror neuron system activity, because MEPs come from primary motor cortex which is closely connected to the mirror neuron regions of the brain. Although indirect, MEPs modulation provides the evidence that in humans the motor system of the observer actively "resonates" on the basis of the various phases of the observed action (i.e. seeing a hand closing onto an object induces a facilitation of the observer's corticospinal channels leading to hand closure). Recent data suggests that these changes in MEP size can be strongly influenced by training on different stimulus-response mappings, with the strongest enhancement for well-learned mappings.[24]

Eye tracking provides another indirect measure that may reflect mirror neuron processing. Upon moving his or her hand, a person's eyes move ahead of the hand to look at the object the person will grasp. Similarly, when watching someone else's action, a person's eyes are also likely to anticipate what the other person will do.[25]

[edit] Evidence against mirror neurons

Two recent studies cast doubt on the importance of mirror neurons in the human brain [26] [27]. These fMRI studies suggest that the signal changes seen in 'mirror neuron regions' of the human brain are not necessarily due to the firing of mirror neurons themselves, but may reflect other processes.

[edit] Development

Human infant data using eye-tracking measures suggest that the mirror neuron system develops before 12 months of age, and that this system may help human infants understand other people's actions.[28] A critical question concerns how mirror neurons acquire mirror properties. Two closely related models postulate that mirror neurons are trained through Hebbian or Associative learning.[29][30] However, if premotor neurons need to be trained by action in order to acquire mirror properties, it is unclear how newborn babies are able to mimic the facial gestures of another person (imitation of unseen actions), as suggested by the work of Meltzoff and Moore (unless this is a special type of imitation not supported by mirror neurons).

[edit] Possible functions

[edit] Understanding intentions

Many studies link mirror neurons to understanding goals and intentions. Fogassi et al. (2005)[31] recorded the activity of 41 mirror neurons in the inferior parietal lobe (IPL) of two rhesus macaques. The IPL has long been recognized as an association cortex that integrates sensory information. The monkeys watched an experimenter either grasp an apple and bring it to his mouth or grasp an object and place it in a cup. In total, 15 mirror neurons fired vigorously when the monkey observed the "grasp-to-eat" motion, but registered no activity while exposed to the "grasp-to-place" condition. For four other mirror neurons, the reverse held true: they activated in response to the experimenter eventually placing the apple in the cup but not to eating it. Only the type of action, and not the kinematic force with which models manipulated objects, determined neuron activity. It was also significant that neurons fired before the monkey observed the human model starting the second motor act (bringing the object to the mouth or placing it in a cup). Therefore, IPL neurons "code the same act (grasping) in a different way according to the final goal of the action in which the act is embedded".[31] They may furnish a neural basis for predicting another individual’s subsequent actions and inferring intention.[31]

[edit] Empathy

Stephanie Preston and Frans de Waal,[32] Jean Decety,[33][34] and Vittorio Gallese[35][36] have independently argued that the mirror neuron system is involved in empathy. A large number of experiments using functional MRI, electroencephalography and magnetoencephalography have shown that certain brain regions (in particular the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and inferior frontal cortex) are active when a person experiences an emotion (disgust, happiness, pain, etc.) and when he or she sees another person experiencing an emotion.[37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42][43] However, these brain regions are not quite the same as the ones which mirror hand actions, and mirror neurons for emotional states or empathy have not yet been described in monkeys. More recently, Christian Keysers at the Social Brain Lab and colleagues have shown that people that are more empathic according to self-report questionnaires have stronger activations both in the mirror system for hand actions[44] and the mirror system for emotions[45], providing more direct support to the idea that the mirror system is linked to empathy.

[edit] Language

See also:Interhemispheric foreign language learning

In humans, functional MRI studies reported that areas homologue to the monkey mirror neuron system have been found in the inferior frontal cortex, close to Broca's area, one of the hypothesized language regions of the brain. This has led to suggestions that human language evolved from a gesture performance/understanding system implemented in mirror neurons. Mirror neurons have been said to have the potential to provide a mechanism for action understanding, imitation learning, and the simulation of other people's behaviour.[46]. This hypothesis is supported by some cytoarchitectonic homologies between monkey premotor area F5 and human Broca's area [47].

[edit] Autism

Some researchers claim there is a link between mirror neuron deficiency and autism. In typical children, EEG recordings from motor areas are suppressed when the child watches another person move, and this is believed to be an index of mirror neuron activity. However, this suppression is not seen in children with autism.[48] Also, children with autism have less activity in mirror neuron regions of the brain when imitating.[49] Finally, anatomical differences have been found in the mirror neuron related brain areas in adults with autism spectrum disorders, compared to non-autistic adults. All these cortical areas were thinner and the degree of thinning was correlated with autism symptom severity, a correlation nearly restricted to these brain regions.[50] Based on these results, some researchers claim that autism is caused by a lack of mirror neurons, leading to disabilities in social skills, imitation, empathy and theory of mind.

[edit] Theory of mind

In Philosophy of mind, mirror neurons have become the primary rallying call of simulation theorists concerning our 'theory of mind.' 'Theory of mind' refers to our ability to infer another person's mental state (i.e., beliefs and desires) from their experiences or their behavior. For example, if you see a person reaching into a jar labeled 'cookies,' you might assume that he wants a cookie (even if you know the jar is empty) and that he believes there are cookies in the jar.

There are several competing models which attempt to account for our theory of mind; the most notable in relation to mirror neurons is simulation theory. According to simulation theory, theory of mind is available because we subconsciously empathize with the person we're observing and, accounting for relevant differences, imagine what we would desire and believe in that scenario.[51][52] Mirror neurons have been interpreted as the mechanism by which we simulate others in order to better understand them, and therefore their discovery has been taken by some as a validation of simulation theory (which appeared a decade before the discovery of mirror neurons).[53] More recently, Theory of Mind and Simulation have been seen as complementary systems, with different developmental time courses.[54] [55] [56]

[edit] Gender differences

The issue of gender differences in empathy is quite controversial and subjects to social desirability and stereotypes. However, a series of recent studies conducted by Yawei Cheng, using a variety of neurophysiological measures, including MEG,[57] spinal reflex excitability, [58] electroencephalography, [59] [60] have documented the presence of a gender difference in the human mirror neuron system, with female participants exhibiting stronger motor resonance than male participants.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Rizzolatti, G., & Craighero, L. (2004). The mirror-neuron system. Annual Review in Neuroscience, 27, 169-92.

- ^ V.S. Ramachandran, "Mirror Neurons and imitation learning as the driving force behind "the great leap forward" in human evolution". Edge Foundation. http://www.edge.org/3rd_culture/ramachandran/ramachandran_p1.html. Retrieved on 2006-11-16.

- ^ a b Dinstein I, Thomas C, Behrmann M, Heeger DJ (2008). "A mirror up to nature". Curr Biol 18 (1): R13–8. doi:. PMID 18177704.

- ^ Christian Keysers and Valeria Gazzola, Progress in Brain Research, 2006, [1]

- ^ Michael Arbib, The Mirror System Hypothesis. Linking Language to Theory of Mind, 2005, retrieved 2006-02-17

- ^ Hugo Théoret, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Language Acquisition: Do As You Hear, Current Biology, Vol. 12, No. 21, pp. R736-R737, 2002-10-29

- ^ Oberman LM, Hubbard EM, McCleery JP, Altschuler EL, Ramachandran VS, Pineda JA., EEG evidence for mirror neuron dysfunction in autism spectral disorders, Brain Res Cogn Brain Res.; 24(2):190-8, 2005-06

- ^ Mirella Dapretto, Understanding emotions in others: mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders, Nature Neuroscience, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 28-30, 2006-01

- ^ Di Pellegrino, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (1992). Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Experimental Brain Research, 91, 176-180.

- ^ Giacomo Rizzolatti et al. (1996) Premotor cortex and the recognition of motor actions, Cognitive Brain Research 3 131-141

- ^ Gallese, V., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., & Rizzolatti, G. (1996). Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain, 119, 593-609.

- ^ Kohler et al., Science, 2002 [2]

- ^ Gazzola et al., Current Biology, 2006 [3]

- ^ Gallese et al, Action recognition in the premotor cortex, Brain, 1996

- ^ Fogassi et al, Parietal Lobe: From Action Organization to Intention Understanding, Science, 2005

- ^ Rizzolatti G., Craighero L., The mirror-neuron system, Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:169-92

- ^ Rizzolatti G., Craighero L., The mirror-neuron system, Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:169-92

- ^ Giacomo Rizzolatti and Laila Craighero Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2004. 27:169–92

- ^ Ferrari PF, Visalberghi E, Paukner A, Fogassi L, Ruggiero A, et al. (2006) Neonatal Imitation in Rhesus Macaques. PLoS Biol 4(9): e302

- ^ Giacomo Rizzolatti and Michael A. Arbib, Language within our grasp, Trends in neurosciences, Vol. 21, No. 5, 1998

- ^ Marco Iacoboni, Roger P. Woods, Marcel Brass, Harold Bekkering, John C. Mazziotta, Giacomo Rizzolatti, Cortical Mechanisms of Human Imitation, Science 286:5449 (1999)

- ^ Dinstein I, Gardner JL, Jazayeri M, Heeger DJ. Executed and observed movements have different distributed representations in human aIPS. J Neurosci. 2008 Oct 29;28(44):11231-9. PMID: 18971465

- ^ Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Pavesi G, Rizzolatti G. Motor facilitation during action observation: a magnetic stimulation study. J Neurophysiol. 1995 Jun;73(6):2608-11.

- ^ Catmur, C., Walsh, V. & Heyes, C. Sensorimotor learning configures the human mirror system. Curr. Biol. 17, 1527–1531 (2007)

- ^ Flanagan JR, Johansson RS. Action plans used in action observation. Nature. 2003 Aug 14;424(6950):769-71.

- ^ Dinstein I, Gardner JL, Jazayeri M, Heeger DJ. J Neurosci. 2008 Oct 29;28(44):11231-9.

- ^ Dinstein I, Hasson U, Rubin N, Heeger DJ. J Neurophysiol. 2007 Sep;98(3):1415-27. Epub 2007 Jun 27.

- ^ Terje Falck-Ytter, Gustaf Gredebäck & Claes von Hofsten (2006), Infants predict other people's action goals[4], Nature Neuroscience 9 (2006)

- ^ Keysers & Perrett, Trends in Cognitive Sciences 8 (2004)

- ^ Brass, M., & Heyes, C. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 9 (2005)

- ^ a b c Fogassi, Leonardo, Pier Francesco Ferrari, Benno Gesierich, Stefano Rozzi, Fabian Chersi, Giacomo Rizzolatti. 2005. Parietal lobe: from action organization to intention understanding. Science 308: 662-667.

- ^ Preston, S. D., & de Waal, F.B.M. (2002) Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25, 1-72.

- ^ Decety, J. (2002). Naturaliser l’empathie [Empathy naturalized]. L’Encéphale, 28, 9-20.

- ^ Decety, J., & Jackson, P.L. (2004). The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 3, 71-100.

- ^ Gallese, V., & Goldman, A.I. (1998). Mirror neurons and the simulation theory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 2, 493-501.

- ^ Gallese, V. (2001). The “Shared Manifold” hypothesis: from mirror neurons to empathy. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 8, 33-50.

- ^ Botvinick, M., Jha, A.P., Bylsma, L.M., Fabian, S.A., Solomon, P.E., & Prkachin, K.M. (2005). Viewing facial expressions of pain engages cortical areas involved in the direct experience of pain. NeuroImage, 25, 312-319.

- ^ Cheng, Y., Yang, C.Y., Lin, C.P., Lee, P.R., & Decety, J. (2008). The perception of pain in others suppresses somatosensory oscillations: a magnetoencephalography study. NeuroImage, 40, 1833-1840.

- ^ Morrison, I., Lloyd, D., di Pellegrino, G., & Roberts, N. (2004). Vicarious responses to pain in anterior cingulate cortex: is empathy a multisensory issue? Cognitive and Affective Behavioral Neuroscience, 4, 270-278.

- ^ Wicker et al., Neuron, 2003 [5]

- ^ Singer et al., Science, 2004 [6]

- ^ Jabbi, Swart and Keysers, NeuroImage, 2006 [7]

- ^ Lamm, C., Batson, C.D., & Decety, J. (2007). The neural substrate of human empathy: effects of perspective-taking and cognitive appraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 42-58.

- ^ Gazzola, Aziz-Zadeh and Keysers, Current Biology, 2006 [8]

- ^ Jabbi, Swart and Keysers, NeuroImage, 2006 [9]

- ^ Skoyles, John R., Gesture, Language Origins, and Right Handedness, Psycholoqy: 11,#24, 2000

- ^ Petrides, Michael, Cadoret, Genevieve, Mackey, Scott (2005). Orofacial somatomotor responses in the macaque monkey homologue of Broca's area, Nature: 435,#1235

- ^ Oberman LM, Hubbard EM, McCleery JP, Altschuler EL, Ramachandran VS, Pineda JA., EEG evidence for mirror neuron dysfunction in autism spectral disorders, Brain Res Cogn Brain Res.; 24(2):190-8, 2005-06

- ^ Mirella Dapretto, Understanding emotions in others: mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders, Nature Neuroscience, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 28-30, 2006-01

- ^ Hadjikhani and others. "Anatomical Differences in the Mirror Neuron System and Social Cognition Network in Autism". Cerebral Cortex. PMID 16306324.

- ^ Gordon, R. (1986). Folk psychology as simulation. Mind and Language 1: 158-171

- ^ Goldman, A. (1989). Interpretation psychologized. Mind and Language 4: 161–185

- ^ Gallese, V., and Goldman, A. (1998). Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mindreading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2: 493–501

- ^ Meltzoff, A.N., & Decety, J. (2003). What imitation tells us about social cognition: A rapprochement between developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience. The Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, London, 358, 491-500.

- ^ Sommerville, J. A., & Decety, J. (2006). Weaving the fabric of social interaction: Articulating developmental psychology and cognitive neuroscience in the domain of motor cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 179-200.

- ^ Keysers C and Gazzola V(2007) Integrating simulation and theory of mind: from self to social cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11(5):194-6[10]

- ^ Cheng, Y., Tzeng, O.J., Decety, J., & Hsieh, J.C. (2006). Gender differences in the human mirror system: a magnetoencephalography study. NeuroReport, 17, 1115-1119.

- ^ Cheng, Y., Decety, J., Hsieh, J.C., Hung, D., & Tzeng, O.J. (2007). Gender differences in spinal excitability during observation of bipedal locomotion. NeuroReport, 18, 887-890.

- ^ Cheng, Y., Decety, J., Yang, C.Y., Lee, S., & Chen, G. (2008). Gender differences in the Mu rhythm during empathy for pain: An electroencephalographic study. Brain Research, in press.

- ^ Cheng, Y., Lee, P., Yang, C.Y., Lin, C.P., & Decety, J. (2008). Gender differences in the mu rythm of the human mirror-neuron system. PLoS ONE, 5, e2113.

[edit] Further reading

- Preston, S. D., & de Waal, F.B.M. (2002). Empathy: Its ultimate and proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25, 1-72.

- Keysers, C., & Gazzola, V. (2006), Towards a unifying neural theory of social cognition, Progress in Brain Research.[11]

- Iacoboni M, Mazziotta JC (2007). "Mirror neuron system: basic findings and clinical applications". Ann Neurol 62: 213. doi:. PMID 17721988.

- Morsella, E., Bargh, J.A., & Gollwitzer, P.M. (Eds.) (2009). Oxford Handbook of Human Action. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rizzolatti G, Fabbri-Destro M, Cattaneo L (2009). "Mirror neurons and their clinical relevance". Nat Clin Pract Neurol 5 (1): 24–34. doi:. PMID 19129788. http://www.nature.com/ncpneuro/journal/v5/n1/full/ncpneuro0990.html.

[edit] See also

- Crosstalk (biology)

- Common coding theory

- Emotional contagion

- Empathy

- Molecular cellular cognition

- Motor cognition

- On Intelligence

- Social brain lab

[edit] External links

- NOVA scienceNOW: Mirror Neurons (including a 14 minute broadcast segment)

- On Mirror Neurons or Why It Is Okay to be a Couch Potato

- Interdisciplines: What do mirror neurons mean? (an online conference on the theoretical implications of mirror neurons)

- Mirrored emotion by Jean Decety from the University of Chicago.

- Neuroscience And Bio Behavioural Reviews.

- LiveScience article on mirror neurons in mind reading

- A primer on mirror-neurons and a critical view on their role in imitation

- Artist Amy Caron's Waves of Mu Mirror Neuron installation and performance art piece

- You remind me of me in the New York Times.