American Revolution

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- In this article, the inhabitants of the thirteen colonies that supported the American Revolution are primarily referred to as "Americans", with occasional references to "Patriots", "Whigs", "Rebels", or "Revolutionaries". Colonists who supported the British in opposing the Revolution are usually referred to as "Loyalists" or "Tories". (See section 2 below for a detailed explanation.) The geographical area of the thirteen colonies that both groups shared is often referred to simply as "America".

The American Revolution refers to the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which the Thirteen Colonies of North America overthrew the governance of the British Empire and then rejected the British monarchy to become the sovereign United States of America. In this period the colonies first rejected the authority of the Parliament of Great Britain to govern them without representation, and formed self-governing independent states.[citation needed] These states then joined[citation needed] against the British to defend that self-governance in the armed conflict from 1775 to 1783 known as the American Revolutionary War (also: American War of Independence). This resulted in the independent states[citation needed] uniting to form one nation, breaking away from the empire in 1776 with the Declaration of Independence, rejecting not only the governance of Parliament, but also now the legitimacy of the monarchy to demand allegiance. After seven years of war came effective American victory on the battlefield in October 1781, with British recognition of the United States' independence and sovereignty in 1783.

The American Revolution included a series of broad intellectual and social shifts that occurred in the early American society, such as the new republican ideals that took hold in the American population. In some states, sharp political debates broke out over the role of democracy in government, with a number of even the most liberal Founding Fathers fearing mob rule. Consequently, many issues of national governance were not settled until the Constitution of the United States (1787), including the United States Bill of Rights (1789) comprising its first 10 amendments, replaced the relatively weak Articles of Confederation (see Federalist Papers) that framed the first attempt at a national government. In contrast to the loose confederation, the Constitution enshrined the natural rights idealized by republican revolutionaries, and guaranteed them under a relatively strong federated government, as well as allowing for dramatically expanded suffrage for national elections. The American shift to republicanism, and the gradually increasing democracy, caused an upheaval of the traditional social hierarchy, and created the ethic that formed the core of American political values.[1]

Origins

The American Revolution was predicated by a number of ideas and events that, combined, led to a political and social separation of colonial possessions from the home nation and a coalescing of those former individual colonies into an independent nation.

Summary

The revolutionary era began in 1763, when the French military threat to British North American colonies ended. Adopting the policy that the colonies should pay an increased proportion of the costs associated with keeping them in the Empire, Britain imposed a series of taxes followed by other laws intended to demonstrate British authority that proved extremely unpopular. Because the colonies lacked elected representation in the governing British Parliament many colonists considered the laws to be illegitimate and a violation of their rights as Englishmen. Additionally, British mercantilist policies benefiting the home country resulted in trade restrictions, which limited the growth of the American economy and artificially constrained colonial merchants' earning potential. In 1772, Patriot groups began to create committees of correspondence, which would lead to their own Provincial Congress in most of the colonies. In the course of two years, the Provincial Congresses or their equivalents rejected the Parliament and effectively replaced the British ruling apparatus in the former colonies, culminating in 1774 with the unifying First Continental Congress.

In response to Patriot protests in Boston over Parliament's attempts to assert authority, the British sent combat troops. Consequently, the colonies mobilized their militias, and fighting broke out in 1775. First ostensibly loyal to King George III, Congress' repeated pleas for royal intervention with Parliament on their behalf only resulted in the states being declared "in rebellion", and Congress traitors. In 1776, representatives from each of the original thirteen independent states voted unanimously to adopt a Declaration of Independence, which now rejected the British monarchy as well as its Parliament. The Declaration established the United States, which was originally governed as a loose confederation through a representative government selected by state legislatures (see Second Continental Congress).

The Americans formed an alliance with France in 1778 that evened the military and naval strengths, later bringing Spain and the Dutch Republic into the conflict by their own alliance with France. Although Loyalists were estimated to comprise 15-20% of the population,[2] throughout the war the Patriots generally controlled 80-90% of the territory; the British could hold only a few coastal cities for any extended period of time. Two main British armies surrendered to the Continental Army, at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781, amounting to victory in the war for the United States. The Second Continental Congress transitioned to the Congress of the Confederation with the ratification of the Articles of Confederation earlier in 1781. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 was ratified by this new national government, and ended British claims to any of the thirteen states.

Liberalism, republicanism, and religion

John Locke's ideas on liberalism greatly influenced the political minds behind the revolution; for instance, his theory of the "social contract" implied that among humanity's natural rights was the right of the people to overthrow their leaders, should those leaders betray the historic rights of Englishmen.[3][4] In terms of writing state and national constitutions, the Americans used Montesquieu's analysis of the ideally "balanced" British Constitution.

A motivating force behind the revolution was the American embrace of a political ideology called "republicanism", which was dominant in the colonies by 1775. The "country party" in Britain, whose critique of British government emphasized that corruption was to be feared, influenced American politicians. The colonists associated the British court with luxury and inherited aristocracy, which the colonials had never welcomed and now increasingly condemned. Corruption was seen as the greatest possible evil, and civic virtue required men to put civic duty ahead of their personal desires. Men had a civic duty to fight for their country.

The "Founding Fathers" were strong advocates of republican values, particularly Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, George Washington, Thomas Paine, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton.[5] For women, "republican motherhood" became the ideal, exemplified by Abigail Adams and Mercy Otis Warren; the first duty of the republican woman was to instill republican values in her children and to avoid luxury and ostentation. The commitment of most Americans to republican values and to their rights, helped bring about the American Revolution, for Britain was increasingly seen as hopelessly corrupt and hostile to American interests; it seemed to threaten to the established liberties that Americans enjoyed.[6] The greatest threat to liberty was depicted as corruption—not just in London but at home as well.[7] The colonists associated it with luxury and, especially, inherited aristocracy, which they condemned.[8]

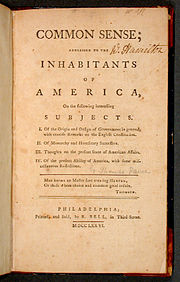

Of course the average Patriots had never heard of Locke nor read other Enlightenment thinkers. “When one farmer who had fought at Concord Bridge was asked … whether he was defending the ideas of such liberal writers, he declared for his part he had never heard of Locke or Sidney, his reading having been limited to the Bible, the Catechism, Watt’s Psalms and Hymns and the Almanac.”[9] Later, most knew about the summary of current political ideas so forcibly expressed in Tom Paine's pamphlet, Common Sense. Though it was printed in 1776 after the revolution had already started, it was a runaway best seller and was often read aloud in taverns, contributing significantly in maintaining popular support for the revolution, advocacy for separation from Great Britain, and recruitment for the Continental Army.

Dissenting (i.e. Protestant non-Church of England) churches of the day have been called the “school of democracy.”[10] Congregationalists, Baptists and Presbyterians based their principles and willingness to rebel against tyrants on their reading of the Old testament, especially Exodus, with its story of the ancient Israelites defying Pharaoh and escaping to freedom.[11] College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) President John Witherspoon was especially influential. [12] His sermons were widely read; one that examined the Israelites rebelling against Pharaoh was distributed to 500 Presbyterian churches seven weeks before the Declaration of Independence.[13] Throughout the colonies, some ministers preached Revolutionary themes in their sermons, while others, especially Church of England members, supported the King.[14] This moral motivation for Independence, unlike Enlightenment thinking, was not limited to an intellectual elite. It included rich and poor, men and women, frontiersmen and townsmen, farmers and merchants.[15]

Incendiary British legislation

The Revolution was predicated by a number of pieces of legislation originating from the British Parliament that, for Americans, were illegitimate acts of a government that had no right to pass laws on Englishmen in the Americas who did not have elected representation in that government. For the British, policy makers saw these laws as necessary to reign-in colonial subjects who had been allowed, in the name of economic development that was designed to benefit the home nation, near-autonomy for too long.

Navigation Acts

The British Empire at the time operated under the mercantile system, where economic assets, or capital, are represented by bullion (gold, silver, and trade value) held by the state, which is best increased through a positive balance of trade with other nations (exports minus imports). Merchantilism suggests that the ruling government should advance these goals through playing a protectionist role in the economy, by encouraging exports and discouraging imports, especially through the use of tariffs. Great Britain regulated the economies of the colonies through the Navigation Acts according to the doctrines of mercantilism. Widespread evasion of these laws had long been tolerated. Eventually, through the use of open-ended search warrants (Writs of Assistance), strict enforcement of these Acts became the practice. In 1761, Massachusetts lawyer James Otis argued that the writs violated the constitutional rights of the colonists. He lost the case, but John Adams later wrote, "American independence was then and there born".

In 1762, Patrick Henry argued the Parson's Cause in Virginia, where the legislature had passed a law and it was vetoed by the King. Henry argued, "that a King, by disallowing Acts of this salutary nature, from being the father of his people, degenerated into a Tyrant and forfeits all right to his subjects' obedience".[16]

Western Frontier

The Proclamation of 1763 restricted colonization across the Appalachian Mountains as this was to be Indian Reserve. Regardless, groups of settlers continued to move west and lay claim to these lands. The proclamation was soon modified and was no longer a hindrance to settlement, but its promulgation and the fact that it had been written without consulting Americans angered the colonists. The Quebec Act of 1774 extended Quebec's boundaries to the Ohio River, shutting out the claims of the thirteen colonies. By then, however, the Americans had little regard for new laws from London; they were drilling militia and organizing for war.[17]

Taxation without representation

By 1763, Great Britain possessed vast holdings in North America. In addition to the thirteen colonies, twenty-two smaller colonies were ruled directly by royal governors. Victory in the Seven Years' War had given Great Britain New France (Canada), Spanish Florida, and the Native American lands east of the Mississippi River. In North America there were six Colonies that remained loyal to Britain. The colonies included: Province of Quebec, Province of Nova Scotia, Colony of Bermuda, Province of West Florida and the Province of East Florida. In 1765 however, the colonists still considered themselves loyal subjects of the British Crown, with the same historic rights and obligations as subjects in Britain.[18]

The British did not expect the colonies to contribute to the interest or the retirement of debt incurred during the French and Indian War, but they did expect a portion of the expenses for colonial defense to be paid by the Americans. Estimating the expenses of defending the continental colonies and the West Indies to be approximately £200,000 annually, the British goal after the end of this war was that the colonies would be taxed for £78,000 of this needed amount.[19] The issues with the colonists were both that the taxes were high and that the colonies had no representation in the Parliament which passed the taxes. Lord North in 1775 argued for the British position that Englishmen paid on average twenty-five shillings annually in taxes whereas Americans paid only sixpence (the average Englishman, however, also earned quite a bit more while receiving more services directly from the government).[20] Colonists, however, as early as 1764, with respect to the Sugar Act, indicated that “the margin of profit in rum was so small that molasses could bear no duty whatever.”[21]

The phrase "No taxation without representation" became popular in many American circles. London argued that the colonists were "virtually represented"; but most Americans rejected the theory that men in London, who knew nothing about their needs and conditions, could represent them.[22]

New taxes 1764

In 1764, Parliament enacted the Sugar Act and the Currency Act, further vexing the colonists. Protests led to a powerful new weapon, the systemic boycott of British goods. The British pushed the colonists even further that same year by also enacting the Quartering Act, which stated that British soldiers were to be cared for by residents in certain areas.

Stamp Act 1765

In 1765 the Stamp Act was the first direct tax ever levied by Parliament on the colonies. All newspapers, almanacs, pamphlets, and official documents—even decks of playing cards—were required to have the stamps. All 13 colonies protested vehemently, as popular leaders such as Patrick Henry in Virginia and James Otis in Massachusetts, rallied the people in opposition. A secret group, the "Sons of Liberty" formed in many towns and threatened violence if anyone sold the stamps, and no one did.[23] In Boston, the Sons of Liberty burned the records of the vice-admiralty court and looted the elegant home of the chief justice, Thomas Hutchinson. Several legislatures called for united action, and nine colonies sent delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October 1765. Moderates led by John Dickinson drew up a "Declaration of Rights and Grievances" stating that taxes passed without representation violated their Rights of Englishmen. Lending weight to the argument was an economic boycott of British merchandise, as imports into the colonies fell from £2,250,000 in 1764 to £1,944,000 in 1765. In London, the Rockingham government came to power and Parliament debated whether to repeal the stamp tax or send an army to enforce it. Benjamin Franklin made the case for the boycotters, explaining the colonies had spent heavily in manpower, money, and blood in defense of the empire in a series of wars against the French and Indians, and that further taxes to pay for those wars were unjust and might bring about a rebellion. Parliament agreed and repealed the tax, but in a "Declaratory Act" of March 1766 insisted that parliament retained full power to make laws for the colonies "in all cases whatsoever".[16]

Townshend Act 1767 and Boston Massacre 1770

In 1767, the Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which placed a tax on a number of essential goods including paper, glass, and tea. Angered at the tax increases, colonists organized a boycott of British goods. In Boston on March 5, 1770, a large mob gathered around a group of British soldiers. The mob grew more and more threatening, throwing snowballs, rocks and debris at the soldiers. One soldier was clubbed and fell. All but one of the soldiers fired into the crowd. Eleven people were hit; Three civilians were killed at the scene of the shooting, and two died after the incident. The event quickly came to be called the Boston Massacre. Although the soldiers were tried and acquitted (defended by John Adams), the widespread descriptions soon became propaganda to turn colonial sentiment against the British. This in turn began a downward spiral in the relationship between Britain and the Province of Massachusetts.

Tea Act 1773

In June 1772, in what became known as the Gaspée Affair, a British warship that had been vigorously enforcing unpopular trade regulations was burned by American patriots. Soon afterwards, Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts reported that he and the royal judges would be paid directly from London, thus bypassing the colonial legislature.

On December 16, 1773, a group of men, led by Samuel Adams and dressed to evoke American Indians, boarded the ships of the government-favored British East India Company and dumped an estimated £10,000 worth of tea on board (approximately £636,000 in 2008) into the harbor. This event became known as the Boston Tea Party and remains a significant part of American patriotic lore.

Intolerable Acts 1774

The British government responded by passing several Acts which came to be known as the Intolerable Acts, which further darkened colonial opinion towards the British. They consisted of four laws enacted by the British parliament.[24] The first was the Massachusetts Government Act, which altered the Massachusetts charter and restricted town meetings. The second Act, the Administration of Justice Act, ordered that all British soldiers to be tried were to be arraigned in Britain, not in the colonies. The third Act was the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston until the British had been compensated for the tea lost in the Boston Tea Party (the British never received such a payment). The fourth Act was the Quartering Act of 1774, which allowed royal governors to house British troops in the homes of citizens without requiring permission of the owner. The First Continental Congress endorsed the Suffolk Resolves, which declared the Intolerable Acts to be unconstitutional, called for the people to form militias, and called for Massachusetts to form a Patriot government.

American political opposition

American political opposition was initially through the colonial assemblies such as the Stamp Act Congress, which included representatives from all thirteen colonies. In 1765, the Sons of Liberty were formed which used public demonstrations, violence and threats of violence to ensure that the British tax laws were unenforceable. While openly hostile to what they considered an oppressive Parliament acting illegally, colonists persisted in numerous petitions and pleas for intervention, to a monarchy which they still claimed loyalty. In late 1772, after the Gaspée Affair, Samuel Adams set about creating new Committees of Correspondence, which linked Patriots in all thirteen colonies and eventually provided the framework for a rebel government. In early 1773 Virginia, the largest colony, set up its Committee of Correspondence, on which Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson served.[25]

In response to the Massachusetts Government Act, Massachusetts Bay and then other colonies formed provisional governments called Provincial Congresses. In 1774, the Continental Congress was formed, made up of representatives from each of the Provincial Congresses or their equivalents, to serve as a provisional national government. Standing Committees of Safety were created in each colony for the enforcement of the resolutions by the Committee of Correspondence, Provincial Congress, and the Continental Congress.

Factions: Patriots, Loyalists and Neutrals

The population of the Thirteen Colonies was far from homogenous, particularly in their political views and attitudes. Loyalties and allegencies varied widely not only within regions and communities, but also within families and sometimes shifted during the course of the Revolution.

Patriots - The Revolutionaries

At the time, revolutionaries were called 'Patriots', 'Whigs', 'Congress-men', or 'Americans'. They included a full range of social and economic classes, but a unanimity regarding the need to defend the rights of Americans. After the war, Patriots such as George Washington, James Madison, John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay were deeply devoted to republicanism while also eager to build a rich and powerful nation, while Patriots such as Patrick Henry, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson represented democratic impulses and the agrarian plantation element that wanted a localized society with greater political equality.

The word "patriot" refers to a person in the colonies who sided with the American Revolution. Calling the revolutionaries "patriots" is a long-standing historical convention, which began prior to the war. For example, the term “Patriot” was in use by American colonists prior to the war during the 1760s, referring to the American Patriot Party. Members of the American Patriot Party also called themselves Whigs after 1768, identifying with members of the British Whig Party, i.e., Radical Whigs and Patriot Whigs, who favored similar colonial policies.[26]

The terminology "Patriot party" was used in Virginia and Massachusetts early in colonial history during the 1600’s, with regard to groups asserting colonial rights[27] and resistance to the King.[28] A Loyalist history published in Canada describes the colonial Patriot Party in 1683 in Massachusetts: “The announcement of this decisive act [writ of quo warranto] on the part of the King produced sensation throughout the colony, and gave rise to the question, “What shall Massachusetts do?” One part of the colony advocated submission; another party advocated resistance. The former were called the “Moderate party,” the latter the “Patriot party”—the commencement of the two parties which were afterwards known as United Empire Loyalists and Revolutionists.”[28] Similarly, the "Patriot party" was known in Virginia in early colonial history during 1618: “By this time [1618] there were two distinct parties, not only in the Virginia Company, but in the Virginia Colony, the one being known as the “Court party,” the other as the “Patriot party…In 1619 the Patriot party secured the right for the settlers in Virginia to elect a Representative Assembly…This was the first representative body ever assembled on the American continent. From the first the representatives began to assert their rights.”[27]

Generally speaking, during the enlightenment era, the word "patriot" was not used interchangeably with "nationalist", as it is today. Rather, the concept of patriotism was linked to enlightenment values concerning a common good, which transcended national and social boundaries. Patriotism, thus, did not require you to stand behind your country at all costs, and there wouldn't necessarily be a contradiction between being a patriot and revolting against king and country.[29]

Class differences among the Patriots

Historians, such as J. Franklin Jameson in the early 20th century, examined the class composition of the Patriot cause, looking for evidence that there was a class war inside the revolution. In the last 50 years, historians have largely abandoned that interpretation, emphasizing instead the high level of ideological unity. Just as there were rich and poor Loyalists, the Patriots were a 'mixed lot', with the richer and better educated more likely to become officers in the Army. Ideological demands always came first: the Patriots viewed independence as a means of freeing themselves from British oppression and taxation and, above all, reasserting what they considered to be their rights. Most yeomen farmers, craftsmen, and small merchants joined the patriot cause as well, demanding more political equality. They were especially successful in Pennsylvania and less so in New England, where John Adams attacked Thomas Paine's Common Sense for the "absurd democratical notions" it proposed.[30]

Loyalists and neutrals

While there is no way of knowing the actual numbers, historians have estimated that about 15-20% of the population remained loyal to the British Crown; these were known at the time as "Loyalists", "Tories", or "King's men".[31][32] They were outnumbered by perhaps 2-1 by the patriots; the Loyalists never controlled territory unless the British Army occupied it. [2] Loyalists were typically older, less willing to break with old loyalties, often connected to the Church of England, and included many established merchants with business connections across the Empire, as well as royal officials such as Thomas Hutchinson of Boston. The revolution sometimes divided families; for example, the Franklins. William Franklin, son of Benjamin Franklin and Governor of New Jersey remained Loyal to the Crown throughout the war and never spoke to his father again. Recent immigrants who had not been fully Americanized were also inclined to support the King, such as recent Scottish settlers in the back country; among the more striking examples of this, see Flora MacDonald.[33]

Most Native Americans rejected pleas that they remain neutral and supported the king. The tribes that depended most heavily upon colonial trade tended to side with the revolutionaries, though political factors were important as well. The most prominent Native American leader siding with the king was Joseph Brant of the Mohawk nation, who led frontier raids on isolated settlements in Pennsylvania and New York until an American army under John Sullivan secured New York in 1779, forcing the Loyalist Indians permanently into Canada.[34]

Some African-American slaves became politically active and supported the king, especially in Virginia where the royal governor actively recruited black men into the British forces in return for manumission, protection for their families, and the promise of land grants. Following the war, many of these "Black Loyalists" settled in Nova Scotia, Upper and Lower Canada, and other parts of the British Empire, where the descendants of some remain today.[35]

A minority of uncertain size tried to stay neutral in the war. Most kept a low profile. However, the Quakers, especially in Pennsylvania, were the most important group that was outspoken for neutrality. As patriots declared independence, the Quakers, who continued to do business with the British, were attacked as supporters of British rule, "contrivers and authors of seditious publications" critical of the revolutionary cause.[36]

After the war, the great majority of the 450,000-500,000 Loyalists remained in America and resumed normal lives. Some, such as Samuel Seabury, became prominent American leaders. Estimates vary, but about 62,000 Loyalists relocated to Canada (46,000 according to the Canadian book on Loyalists, True Blue), Britain (7,000) or to Florida or the West Indies (9,000). This made up approximately 2% of the total population of the colonies. When the Loyalists left the South in 1783, they took thousands of blacks with them as slaves to the British West Indies[37].

Women

Several types of women contributed to the American Revolution in multiple ways. Like men, women participated on both sides of the war. Among women, Anglo-Americans, African Americans, and Native Americans also divided between the Patriot and Loyalist causes.

While formal Revolutionary politics did not include women, ordinary domestic behaviors became charged with political significance as patriot women confronted a war that permeated all aspects of political, civil, and domestic life. They participated by boycotting British goods, spying on the British, following armies as they marched, washing, cooking, and tending for soldiers, delivering secret messages, and in a few cases like Deborah Samson fighting disguised as men. Above all, they continued the agricultural work at home to feed the armies and their families.[38]

The boycott of British goods required the willing participation of American women; the boycotted items were largely household items such as tea and cloth. Women had to return to spinning and weaving—skills that had fallen into disuse. In 1769, the women of Boston produced 40,000 skeins of yarn, and 180 women in Middletown, Massachusetts, wove 20,522 yards (18,765 m) of cloth.[39]

A crisis of political loyalties could also disrupt the fabric of colonial America women’s social worlds: whether a man did or did not renounce his allegiance to the king could dissolve ties of class, family, and friendship, isolating women from former connections. A woman’s loyalty to her husband, once a private commitment, could become a political act, especially for women in America committed to men who remained loyal to the king. Legal divorce, usually rare, was granted to patriot women whose husbands supported the king.[40]

Other participants

Native Americans

For Native Americans, the American Revolution was not a war of patriotism or independence. The great majority supported the British cause. Some tried to remain neutral, seeing little value in participating yet again in a European conflict. A few supported the American cause. The losers lost their lands, especially in New York state, and were driven into Canada. African Americans, both men and women, understood Revolutionary rhetoric as promising freedom and equality. These hopes were not realized. Both British and American governments made promises of freedom for service and some slaves attempted to better their lives by fighting in or assisting one or the other armies. Starting in 1777 abolition occurred in the North, usually on a gradual schedule with no payments to the owners, but slavery persisted in the South and took on new life after the cotton gin made for a very profitable new crop.[41]

Slaves

During the Revolution, efforts were made by the British to turn slavery against the Americans,[32] but historian David Brion Davis explains the difficulties with a policy of wholesale arming of the slaves:

But England greatly feared the effects of any such move on its own West Indies, where Americans had already aroused alarm over a possible threat to incite slave insurrections. The British elites also understood that an all-out attack on one form of property could easily lead to an assault on all boundaries of privilege and social order, as envisioned by radical religious sects in Britain’s seventeenth-century civil wars.[42]

Davis underscored the British dilemma: "Britain, when confronted by the rebellious American colonists, hoped to exploit their fear of slave revolts while also reassuring the large number of slaveholding Loyalists and wealth Caribbean planters and merchants that their slave property would be secure".[43] The colonists accused the British of encouraging slave revolts.[44]

American advocates of independence were commonly lampooned in Britain for their hypocritical calls for freedom, while many of their leaders were slave-holders. Samuel Johnson observed "how is it we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the [slave] drivers of the negroes?"[45] Benjamin Franklin countered by criticizing the British self-congratulation about "the freeing of one negro" (Somersert) while they continued to permit the Slave Trade.[46][47]

In the North, slavery was first abolished in the state constitution of Vermont in 1777, in Massachusetts in 1780, and New Hampshire in 1784. Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Rhode Island adopted systems of gradual emancipation during these years, freeing the children of slaves at birth. All the northern states passed laws to end slavery, the last being New Jersey in 1804. Slavery was banned in the Northwest Territories, but no southern state abolished it.

During the Revolution, some African American writers rose to prominence, notable Phyllis Wheatley, who came to public attention when her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral appeared in London in 1773, while she was still a domestic slave in Boston. Kidnapped in Africa as young girl and converted to Christianity during the Great Awakening, Wheatley wrote poems combining piety and a concern for African Americans.[47]

Military hostilities begin

The Battle of Lexington and Concord took place April 19, 1775, when the British sent a force of roughly 1000 troops to confiscate arms and arrest revolutionaries in Concord.[48] They clashed with the local militia, marking the first fighting of the American Revolutionary War. The news aroused the 13 colonies to call out their militias and send troops to besiege Boston. The Battle of Bunker Hill followed on June 17, 1775. While a British victory, it was made a victory by heavy losses on the British side; about 1,000 British casualties from a garrison of about 6,000, as compared to 500 American casualties from a much larger force.[49][50]

The Second Continental Congress convened in 1775, after the war had started. The Congress created the Continental Army and extended the Olive Branch Petition to the crown as an attempt at reconciliation. King George III refused to receive it, issuing instead the Proclamation of Rebellion, requiring action against the "traitors".

In the winter of 1775, the Americans invaded Canada. Richard Montgomery captured Montreal but a joint attack on Quebec with the help of Benedict Arnold failed.

In March 1776, with George Washington as commander, the Continental Army forced the British to evacuate Boston, withdrawing their garrison to Halifax, Nova Scotia. The revolutionaries were in control of governments throughout the 13 colonies and were ready to declare independence. While there still were many Loyalists, they were no longer in control anywhere by July 1776, and all of the Royal officials had fled.[51]

Prisoners

In August 1775, the King declared Americans in arms against royal authority to be traitors to the Crown. The British government at first started treating captured rebel combatants as common criminals and preparations were made to bring them to trial for treason. American Secretary Lord Germain and First Lord of the Admiralty Lord Sandwich were especially eager to do so, with a particular emphasis on those who had previously served in British units (and thereby sworn an oath of allegiance to the crown).

Many of the prisoners taken by the British at Bunker Hill apparently expected to be hanged, but British authorities declined to take the next step: treason trials and executions. There were tens of thousands of Loyalists under American control who would have been at risk for treason trials of their own (by the Americans)[clarification needed], and the British built much of their strategy around using these Loyalists. After the surrender at Saratoga in 1777, there were thousands of British prisoners in American hands who were effectively hostages.

Therefore no American prisoners were put on trial for treason, and although most were badly treated and many died nonetheless,[52][53] eventually they were technically accorded the rights of belligerents. In 1782, by act of Parliament, they were officially recognized as prisoners of war rather than traitors. At the end of the war, both sides released their surviving prisoners.[54]

Creating new state constitutions

Following the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775, the Patriots had control of most of the territory and population; the Loyalists were powerless.[dubious ] In all thirteen colonies, Patriots had overthrown their existing governments, closing courts and driving British governors, agents and supporters from their homes. They had elected conventions and "legislatures" that existed outside of any legal framework; new constitutions were used in each state to supersede royal charters. They declared they were states now, not colonies.[55]

On January 5, 1776, New Hampshire ratified the first state constitution, six months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Then, in May 1776, Congress voted to suppress all forms of crown authority, to be replaced by locally created authority. Virginia, South Carolina, and New Jersey created their constitutions before July 4. Rhode Island and Connecticut simply took their existing royal charters and deleted all references to the crown.[56]

The new states had to decide not only what form of government to create, they first had to decide how to select those who would craft the constitutions and how the resulting document would be ratified. In states where the wealthy exerted firm control over the process, such as Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, New York and Massachusetts, the results were constitutions that featured:

- Substantial property qualifications for voting and even more substantial requirements for elected positions (though New York and Maryland lowered property qualifications);[55]

- Bicameral legislatures, with the upper house as a check on the lower;

- Strong governors, with veto power over the legislature and substantial appointment authority;

- Few or no restraints on individuals holding multiple positions in government;

- The continuation of state-established religion.

In states where the less affluent had organized sufficiently to have significant power—especially Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New Hampshire—the resulting constitutions embodied

- universal white manhood suffrage, or minimal property requirements for voting or holding office (New Jersey enfranchised some property owning widows, a step that it retracted 25 years later);

- strong, unicameral legislatures;

- relatively weak governors, without veto powers, and little appointing authority;

- prohibition against individuals holding multiple government posts;

Whether conservatives or radicals held sway in a state did not mean that the side with less power accepted the result quietly. The radical provisions of Pennsylvania's constitution lasted only fourteen years. In 1790, conservatives gained power in the state legislature, called a new constitutional convention, and rewrote the constitution. The new constitution substantially reduced universal white-male suffrage, gave the governor veto power and patronage appointment authority, and added an upper house with substantial wealth qualifications to the unicameral legislature. Thomas Paine called it a constitution unworthy of America.[57]

Declaration of Independence, 1776

On January 10, 1776, Thomas Paine published a political pamphlet entitled Common Sense arguing that the only solution to the problems with Britain was republicanism and independence from Great Britain.[58] In the ensuing months, before the United States as a political unit declared its independence, several states individually declared their independence. Virginia, for instance, declared its independence from Great Britain on May 15.

On July 2, 1776, Congress voted the independence of the United States; two days later, on July 4, it adopted the Declaration of Independence, which date is now celebrated as Independence Day in the United States. The war had been underway since April 1775, and until this point, the states had sought favorable peace terms; compromise was no longer a possibility, despite belated British effotrts to come to a political resolution.[59]

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, commonly known as the Articles of Confederation, formed the first governing document of the United States of America, combining the sovereign states into a loose confederation. The Second Continental Congress adopted the Articles in November 1777, and began operating under their terms. They were formally ratified by the last state legislature on March 1, 1781, the Continental Congress was dissolved, and the new government of the United States in Congress Assembled was formed.[60][61]

Defending the Revolution

British return: 1776-1777

After Washington forced the British out of Boston in spring, 1776, neither the British nor the Loyalists controlled any significant areas. This opened the way for the unanimous Declaration of Independence in July. The British, however, were massing forces at their great naval base at Halifax, Nova Scotia. They returned in force in July 1776, landing in New York and defeating Washington's Continental Army in August at the Battle of Brooklyn in one of the largest engagements of the war. The British requested a meeting with representatives from Congress to negotiate an end to hostilities, and a delegation including John Adams and Benjamin Franklin met Howe on Staten Island in New York Harbor on September 11. Howe demanded a retraction of the Declaration of Independence, which was refused, and negotiations ended until 1781. The British then quickly seized New York City and nearly captured Washington. They made the city their main political and military base of operations in North America, holding it until November 1783. New York City became the destination for Loyalist refugees, and a focal point of Washington's intelligence network.[62] The British also took New Jersey, but in a surprise attack in late December, 1776, Washington crossed the Delaware River into New Jersey and defeated Hessian and British armies at Trenton and Princeton, thereby regaining New Jersey. The victories gave an important boost to pro-independence supporters at a time when morale was flagging, and have become iconic images of the war.

In 1777, as part of a grand strategy to end the war, the British sent an invasion force from Canada to seal off New England, which the British perceived as the primary source of agitators. In a major case of mis-coordination, the British army in New York City went to Philadelphia which it captured from Washington. The invasion army under Burgoyne waited in vain for reinforcements from New York, and became trapped upstate. It surrendered after the Battle of Saratoga, New York, in October 1777. From early October 1777 until November 15 a pivotal siege at Fort Mifflin, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania distracted British troops and allowed Washington time to preserve the Continental Army by safely leading his troops to harsh winter quarters at Valley Forge.

American alliances after 1778

Saratoga encouraged the French to formally enter the war, as Benjamin Franklin negotiated a permanent military alliance in early 1778, significantly becoming the first country to officially recognise the declaration of independence. William Pitt spoke out in parliament urging Britain to make peace in America, and unite with America against France,[63] while other British politicians who had previously supported independence now turned against the American rebels for allying with the old mutual enemy.

Later Spain (in 1779) and the Dutch (1780) became allies of the French, leaving the British Empire to fight a global war alone without major allies, and requiring it to slip through a combined blockade of the Atlantic. The American theatre thus became only one front in Britain's war.[64] The British were forced to withdraw troops from continental America to reinforce the sugar-producing Caribbean islands, which were considered more valuable.

Because of the alliance with France and the deteriorating military situation, Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, evacuated Philadelphia to reinforce New York City. General Washington attempted to intercept the retreating column, resulting in the Battle of Monmouth Court House, the last major battle fought in the north. After an inconclusive engagement, the British successfully retreated to New York City. The northern war subsequently became a stalemate, as the focus of attention shifted to the smaller southern theatre.[64]

The British move South, 1778-1783

The British strategy in America now concentrated on a campaign in the southern colonies. With fewer regular troops at their disposal, the British commanders saw the Southern Strategy as a more viable plan, as the south was perceived as being more strongly Loyalist, with a large population of poorer recent immigrants as well as large numbers of African Americans, both groups who tended to favour them.

In late December 1778, the British had captured Savannah. In 1780 they launched a fresh invasion and took Charleston as well. A significant victory at the Battle of Camden meant that government forces soon controlled most of Georgia and South Carolina. The British set up a network of forts inland, hoping the Loyalists would rally to the flag. Despite the disaster at Saratoga, they once again appeared to have gained the upper hand. There was even a consideration of ten state independence (with the three southernmost colonies remaining British).

Not enough Loyalists turned out, however, and the British had to fight their way north into North Carolina and Virginia, with a severely weakened army. Behind them much of the territory they had already captured dissolved into a chaotic guerrilla war, fought predominantly between bands of Loyalist and rebel Americans, which negated many of the gains the British had previously made.

Yorktown 1781

The southern British army marched to Yorktown, Virginia where they expected to be rescued by a British fleet which would take them back to New York.[65] When that fleet was defeated by a French fleet, however, they became trapped in Yorktown.[66] In October 1781 under a combined siege by the French and Continental armies, the British under the command of General Cornwallis, surrendered. However, Cornwallis was so embarrassed at his defeat that he had to send his second in command to surrender for him.[67]

News of the defeat effectively ended major offensive operations in America. Support for the conflict had never been strong in Britain, where many sympathised with the rebels, but now it reached a new low.[68]

Although King George III personally wanted to fight on, his supporters lost control of Parliament, and no further major land offensives were launched in the American Theatre.[64] A final naval battle was fought on March 10, 1783 off the coast of Cape Canaveral by Captain John Barry and his crew of the USS Alliance with three British warships led by HMS Sybil, who were trying to take the payroll of the Continental Army.

Peace treaty

The peace treaty with Britain, known as the Treaty of Paris, gave the U.S. all land east of the Mississippi River and south of the Great Lakes, though not including Florida (On September 3, 1783, Britain entered into a separate agreement with Spain under which Britain ceded Florida back to Spain.). The Native American nations actually living in this region were not a party to this treaty and did not recognize it until they were defeated militarily by the United States. Issues regarding boundaries and debts were not resolved until the Jay Treaty of 1795.[69]

Immediate aftermath

Interpretations

Interpretations about the effect of the Revolution vary. Though contemporary participants referred to the events as "the revolution",[70] at one end of the spectrum is the view that the American Revolution was not "revolutionary" at all, contending that it did not radically transform colonial society but simply replaced a distant government with a local one.[71] More recent scholarship pioneered by historians such as Bernard Bailyn, Gordon Wood, and Edmund Morgan accepts the contemporary view of the participants that the American Revolution was a unique and radical event that produced deep changes and had a profound impact on world affairs, based on an increasing belief in the principles of republicanism, such as peoples' natural rights, and a system of laws chosen by the people.[72]

Loyalist expatriation

For roughly five percent of the inhabitants of the United States, defeat was followed by self-exile. Approximately 62,000 United Empire Loyalists left the newly founded republic, most settling in the remaining British colonies in North America, such as the Province of Quebec (concentrating in the Eastern Townships), Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia. The new colonies of Upper Canada (now Ontario) and New Brunswick were created by Britain for their benefit.[73]

Worldwide influence

After the Revolution, genuinely democratic politics, such as those of Matthew Lyon, became possible,[clarification needed] despite the opposition and dismay of the Federalist Party.[neutrality disputed][74] The rights of the people were incorporated into state constitutions. Thus came the widespread assertion of liberty, individual rights, equality and hostility toward corruption which would prove core values of republicanism to Americans. The greatest challenge to the old order in Europe was the challenge to inherited political power and the democratic idea that government rests on the consent of the governed. The example of the first successful revolution against a European empire, and the first successful establishment of a republican form of democratically elected government since ancient Rome, provided a model for many other colonial peoples who realized that they too could break away and become self-governing nations with directly elected representative government.[75]

In 1777, Morocco was the first state to recognize the independence of the United States of America. The two countries signed the Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship ten years later. Friesland, one of the seven United Provinces of the Dutch Republic, was the next to recognize American independence (February 26, 1782), followed by the Staten-Generaal of the Dutch Republic on April 19, 1782). John Adams became the first US Ambassador in The Hague.[76] The American Revolution was the first wave of the Atlantic Revolutions that took hold in the French Revolution, the Haitian Revolution, and the Latin American wars of independence. Aftershocks reached Ireland in the 1798 rising, in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and in the Netherlands.[77]

The Revolution had a strong, immediate impact in Great Britain, Ireland, the Netherlands, and France. Many British and Irish Whigs spoke in favor of the American cause. The Revolution, along with the Dutch Revolt (end of the 16th century) and the English Civil War (in the 17th century), was one of the first lessons in overthrowing an old regime for many Europeans who later were active during the era of the French Revolution, such as Marquis de Lafayette. The American Declaration of Independence had some impact on the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 1789.[78][79]

The North American states' newly-won independence from the British Empire resulted in the abolition of slavery in some Northern states 51 years before it would be banned in the British colonies, and allowed slavery to continue in the Southern states until 1865, 32 years after it was banned in all British colonies.

National debt

The national debt after the American Revolution fell into three categories. The first was the $11 million owed to foreigners—mostly debts to France during the American Revolution. The second and third—roughly $24 million each—were debts owed by the national and state governments to Americans who had sold food, horses, and supplies to the revolutionary forces. Congress agreed that the power and the authority of the new government would pay for the foreign debts. There were also other debts that consisted of promissory notes issued during the Revolutionary War to soldiers, merchants, and farmers who accepted these payments on the premise that the new Constitution would create a government that would pay these debts eventually. The war expenses of the individual states added up to $114,000,000, compared to $37 million by the central government.[80] In 1790, at the recommendation of first Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Congress combined the state debts with the foreign and domestic debts into one national debt totaling $80 million. Everyone received face value for wartime certificates, so that the national honor would be sustained and the national credit established.

See also

- Timeline of United States revolutionary history (1760-1789)

- List of plays and films about the American Revolution

Bibliography

Notes

- ^ Wood (1992); Greene & Pole (1994) ch 70

- ^ a b Calhoon, "Loyalism and neutrality" in Greene and Pole, A Companion to the American Revolution (2000) p.235

- ^ Charles W. Toth, Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite: The American Revolution & the European Response. (1989) p. 26.

- ^ page 101, Philosophical Tales, by Martin Cohen, (Blackwell 2008)

- ^ Robert E. Shalhope, "Toward a Republican Synthesis," William and Mary Quarterly, 29 (Jan. 1972), pp 49-80

- ^ Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (1967)

- ^ Gordon S. Wood The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1992) pp 174-5

- ^ Gordon S. Wood The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1992) p 35

- ^ Patricia U. Bonomi, “Under the Cope of Heaven. Religion, Society and Politics in Colonial America”, (1986), p.5

- ^ Bonomi, p 186

- ^ David Gelernter, Americanism, the Fourth Great Western Religion, (2007). pp 64,71,81,96

- ^ Michael Novak, "On Two Wings. Humble Faith and Common Sense at the American Founding", (2002), p. 15

- ^ Novak, p. 15

- ^ William H. Nelson, The American Tory (1961) esp p. 186

- ^ Bonomi, p. 186, Chapter 7 “Religion and the American Revolution

- ^ a b Miller (1943)

- ^ Greene & Pole (1994) ch 15

- ^ Greene & Pole (1994) ch 11

- ^ Middlekauff pg. 62.

- ^ Miller, p.89

- ^ Miller pg. 101

- ^ William S. Carpenter, "Taxation Without Representation" in Dictionary of American History, Volume 7 (1976); Miller (1943)

- ^ Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (1972)

- ^ Miller (1943) pp 353-76

- ^ Greene & Pole (1994) ch 22-24

- ^ Murray, Stuart: Smithsonian Q & A: The American Revolution, HarperCollins Publishers by Hydra Publishing (in collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution), New York (2006) p. 31.

- ^ a b The Outlook, Vol. LXXXVI, May-August 1907, The Outlook Co., New York (1907) p. 61.

- ^ a b Ryerson, Egerton: The Loyalists of America and Their Times, Vol. I, Second Edition, William Briggs, Toronto (1880) p. 208.

- ^ Chisick, Harvey, Historical Dictionary of the Enlightenment, pp. 313–314, http://books.google.com/books?id=5N-wqTXwiU0C&pg=PA313&lpg=PA313&dq=Patriotism+and+the+enlightenment&source=web&ots=085cTPNN3r&sig=X_jzMPlYg5tvovEGkty_SDVYCD8&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=8&ct=result#PPA313,M1

- ^ Nash (2005); Resch (2006)

- ^ Staff. Tory, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ^ a b Revolutionary War: The Home Front, The Library of Congress

- ^ Calhoon, Robert M. "Loyalism and neutrality" in Greene and Pole, The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (1991)

- ^ Lawrence Nash, Freedom Bound, in The Beaver: Canada's History Magazine. [1] Feb/Mar., 2007, pp. 16-23]; Colin G. Calloway, The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities (1995)

- ^ Hill (2007), see also blackloyalist.com

- ^ Gottlieb 2005

- ^ Greene & Pole (1994) ch 20-22

- ^ Carol Berkin, Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence (2005)

- ^ Berkin (2005); Greene & Pole (1994) ch 41

- ^ Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (1997) ch 4, 6; also see Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women (1980)

- ^ Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the American Revolution (1961)

- ^ Davis p. 148

- ^ Davis p. 149

- ^ Schama p.28-30 p. 78-90

- ^ Weintraub p.7

- ^ Schama p.75

- ^ a b Hochschild p.50-51

- ^ Morrisey p.35

- ^ Harvey p.208-210

- ^ Urban p.74

- ^ Miller (1948) p. 87

- ^ Onderdonk, Henry. "Revolutionary Incidents of Suffolk and Kings Counties; With an Account of the Battle of Long Island and the British Prisons and Prison-Ships at New York". ISBN 978-0804680752

- ^ Dring, Thomas and Greene, Albert. "Recollections of the Jersey Prison Ship" (American Experience Series, No 8), 1986 (originally printed 1826). ISBN 978-0918222923

- ^ John C. Miller, Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783 1948. Page 166.

- ^ a b Nevins (1927); Greene & Pole (1994) ch 29

- ^ Nevins (1927)

- ^ Wood (1992)

- ^ Greene and Pole (1994) ch 26.

- ^ Greene and Pole (1994) ch 27.

- ^ Greene and Pole (1994) ch 30;

- ^ Klos, Stanley L. (2004). President Who? Forgotten Founders. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Evisum, Inc.. ISBN 0-9752627-5-0.

- ^ Schecter, Barnet. The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution. (2002); McCullough, 1776 (2005)

- ^ Weintraub p.

- ^ a b c Mackesy, 1992; Higginbotham (1983)

- ^ Harvey p.493-95

- ^ Harvey p.502-06

- ^ Harvey p.515

- ^ Harvey p.528

- ^ Miller (1948), pp 616-48

- ^ McCullough, David. John Adams. Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN-9780743223133

- ^ Greene, Jack. "The American Revolution Section 25". The American Historical Review. http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/105.1/ah000093.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-06.

- ^ Wood (2003)

- ^ Van Tine (1902)

- ^ Wood, Radicalism, p. 278-9

- ^ Palmer, (1959)

- ^ "Frisians first to recognize USA! (After an article by Kerst Huisman, Leeuwarder Courant 29th Dec. 1999)". http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Atrium/6641/fry_usa.htm. Retrieved on 2006-11-11.

- ^ Palmer, (1959); Greene & Pole (1994) ch 53-55

- ^ Palmer, (1959); Greene & Pole (1994) ch 49-52.

- ^ "Enlightenment and Human Rights". http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/chap3a.html. Retrieved on 2007-01-06.

- ^ Jensen, The New Nation (1950) p 379

Reference works

- Ian Barnes and Charles Royster. The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution (2000), maps and commentary

- Blanco, Richard. The American Revolution: An Encyclopedia 2 vol (1993), 1850 pages

- Boatner, Mark Mayo, III. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. (1966); revised 1974. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1; new expanded edition 2006 ed. by Harold E. Selesky

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO 2006) 5 vol; 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- Greene, Jack P. and J. R. Pole, eds. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (1994), 845pp; emphasis on political ideas; revised edition (2004) titled A Companion to the American Revolution

- Nash, Lawrence Freedom Bound, in The Beaver: Canada's History Magazine.[2] Feb/Mar., 2007, by Canada's National History Society. pp. 16–23. ISSN 0005-7517

- Purcell, L. Edward. Who Was Who in the American Revolution (1993); 1500 short biographies

- Resch, John P., ed. Americans at War: Society, Culture and the Homefront vol 1 (2005)

Primary sources

- The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence (2001), Library of America, 880pp

- Commager, Henry Steele and Morris, Richard B., eds. The Spirit of 'Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution As Told by Participants (1975) (ISBN 0-06-010834-7) short excerpts from hundreds of official and unofficial primary sources

- Dring, Thomas and Greene, Albert. Recollections of the Jersey Prison Ship (American Experience Series, No 8), 1986 (originally printed 1826). ISBN 978-0918222923

- Humphrey, Carol Sue ed. The Revolutionary Era: Primary Documents on Events from 1776 to 1800 Greenwood Press, 2003

- Morison, Samuel E. ed. Sources and Documents Illustrating the American Revolution, 1764-1788, and the Formation of the Federal Constitution (1923). 370 pp online version

- Onderdonk, Henry. Revolutionary Incidents of Suffolk and Kings Counties; With an Account of the Battle of Long Island and the British Prisons and Prison-Ships at New York. ISBN 978-0804680752

- Tansill, Charles C. ed.; Documents Illustrative of the Formation of the Union of the American States. Govt. Print. Office. (1927). 1124 pages online version

- Martin Kallich and Andrew MacLeish, eds. The American Revolution through British eyes (1962) primary documents

Surveys

- Bancroft, George. History of the United States of America, from the discovery of the American continent. (1854-78), vol 4-10 online edition

- Cogliano, Francis D. Revolutionary America, 1763-1815; A Political History (2000), British textbook

- Harvey, Robert A few bloody noses: The American Revolutionary War (2004)

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence: Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763-1789 (1983) Online in ACLS History E-book Project. Comprehensive coverage of military and other aspects of the war.

- Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains: The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (2006)

- Jensen, Merrill. The Founding of a Nation: A History of the American Revolution 1763-1776. (2004)

- Bernhard Knollenberg, Growth of the American Revolution: 1766-1775 (2003) online edition

- Lecky, William Edward Hartpole. The American Revolution, 1763-1783 (1898), British perspective online edition

- Mackesy, Piers. The War for America: 1775-1783 (1992), British military study online edition

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (2005). The 1985 version is available online at online edition

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783 (1948) online edition

- Miller, John C. Origins of the American Revolution (1943) online edition

- Morrissey, Brendan. Boston 1775:The Shot Heard Around The World. Osprey (1993)

- Schama, Simon. Rough Crossings: Britain, The Slaves and the American Revolution (2006)

- Urban, Mark. Generals:Ten British Commanders who shaped the World (2005)

- Weintraub, Stanley. Iron Tears: Rebellion in America 1775-83 (2005)

- Wood, Gordon S. The American Revolution: A History (2003), short survey

- Wrong, George M. Washington and His Comrades in Arms: A Chronicle of the War of Independence (1921) online short survey by Canadian scholar

Specialized studies

- Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Harvard University Press, 1967. ISBN 0-674-44301-2

- Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study on the History of Political Ideas (1922)online edition

- Samuel Flagg Bemis. The Diplomacy of the American Revolution (1935) online edition

- Berkin, Carol.Revolutionary Mothers: Women in the Struggle for America's Independence (2006)

- Breen, T. H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (2005)

- Crow, Jeffrey J. and Larry E. Tise, eds. The Southern Experience in the American Revolution (1978)

- Davis, David Brion. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery n the New World. (2006)

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing (2004). 1776 campaigns; Pulitzer prize. ISBN 0–195–17034–2

- Greene, Jack, ed. The Reinterpretation of the American Revolution (1968) collection of scholarly essays

- Kerber, Linda K. Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (1979)

- McCullough, David. 1776 (2005). ISBN 0-7432-2671-2

- Morris, Richard B. ed. The Era of the American revolution (1939); older scholarly essays

- Nash, Gary B. The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America. (2005). ISBN 0-670-03420-7

- Nevins, Allan; The American States during and after the Revolution, 1775-1789 1927. online edition

- Norton, Mary Beth. Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (1980)

- Palmer, Robert R. The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800. vol 1 (1959) online edition

- Resch, John Phillips and Walter Sargent, eds. War And Society in the American Revolution: Mobilization And Home Fronts (2006)

- Rothbard, Murray, Conceived in Liberty (2000), Volume III: Advance to Revolution, 1760-1775 and Volume IV: The Revolutionary War, 1775-1784. ISBN 0-945466-26-9.

- Schecter, Barnet. The Battle for New York: The City at the Heart of the American Revolution. Walker & Company. New York. October 2002. ISBN 0-8027-1374-2

- Shankman, Andrew. Crucible of American Democracy: The Struggle to Fuse Egalitarianism and Capitalism in Jeffersonian Pennsylvania. University Press of Kansas, 2004.

- Van Tyne, Claude Halstead. American Loyalists: The Loyalists in the American Revolution (1902)

- Volo, James M. and Dorothy Denneen Volo. Daily Life during the American Revolution (2003)

- Wahlke, John C. ed. The Causes of the American Revolution (1967) readings

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution: How a Revolution Transformed a Monarchical Society into a Democratic One Unlike Any That Had Ever Existed. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

External links

- Library of Congress Guide to the American Revolution

- American Revolution Digital Learning Project[3]New-York Historical Society

- PBS Television Series

- Smithsonian study unit on Revolutionary Money

- http://www.theamericanrevolution.org

- Haldimand Collection Letters regarding the war to important generals. Fully indexed

- The American Revolution

- "Military History of Revolution" essay by Richard Jensen with links to documents, maps, URLs

- American Independence Museum

- Black Loyalist Heritage Society

- Spanish and Latin American contribution to the American Revolution

- American Archives: Documents of the American Revolution at Northern Illinois University Libraries