Battle of Marathon

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Battle of Marathon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Greco-Persian Wars | |||||||

The plain of Marathon today |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Athens, Plataea |

Persian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Miltiades the Younger, Callimachus † |

Datis, Artaphernes |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 7,000 to 10,000 Athenians, 1,000 Plataeans |

c.25,000 troops 600 ships |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 192 Athenians, 11 Plataeans (Herodotus) |

6,400 dead 7 ships captured (Herodotus) |

||||||

|

|||||

The Battle of Marathon (Greek: Μάχη τοῡ Μαραθῶνος, Machē tou Marathōnos) took place in 490 BC during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes.and was the culmination of the first attempt by the of Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate Greece. The first Persian invasion was a response to Greek involvement in the Ionian Revolt, when Athens and Eretria had sent a force to support the cities of Ionia in their attempt to overthrow Persian rule. The Athenian and Eretrian had succeeded in capturing and burning Sardis, but was then forced to retreat with heavy losses. In response to this raid, the Persian king Darius I swore to have revenge on Athens and Eretria.

Once the Ionian revolt was finally crushed by the Persian victory at the Battle of Lade, Darius began to plan to subjugate Greece. In 490 BC, he sent a naval task force under Datis and Artaphernes across the Aegean, to subjugate the Cyclades, and then to make punitive attacks on Athens and Eretria. Reaching Euboea in mid-summer after a succesful campaign in the Aegean, the Persians proceeded to besiege and capture Eretria. The Persian force then sailed for Attica, landing in the bay near the town of Marathon. The Athenians, joined by a small force from Plataea, marched to Marathon, and succeeded in blocking the two exits from the plain of Marathon. Stalemate ensued for five days, before the Athenians (for reasons that are not completely clear) decided to attack the Persians. Despite the numerical advantage of the Persians, the hoplites proved devastatingly effective against the more lightly armed Persian infantry, routing the wings before turning in on the centre of the Persian line.

The defeat at Marathon marked the end of the first Persian invasion of Greece, and the Persian force retreated to Asia. Darius then began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition. After Darius then died, his son Xerxes I re-started the preparations for a second invasion of Greece, which finally began in 480 BC.

The Battle of Marathon was a watershed in the Greco-Persian wars, showing the Greeks that the Persians could be beaten; the eventual Greek triumph in these wars can be seen to begin at Marathon. Since the following two hundred years saw the rise of the Classical Greek civilization, which has been enduringly influential in western society, the Battle of Marathon is often seen as the pivotal moment in European history. For instance, John Stuart Mill famously suggested that "the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings". The Battle of Marathon is perhaps now more famous as the inspiration for the Marathon race. Although historically inaccurate, the legend of a Greek messenger running to Athens with news of the victory became the inspiration for this athletics event, introduced at the 1896 Athens Olympics, and originally run between Marathon and Athens.

Contents |

[edit] Sources

The main primary source for the Greco-Persian Wars is the Greek historian Herodotus. Herodotus, who has been called the 'Father of History',[1] was born in 484 BC in Halicarnassus, Asia Minor (then under Persian overlordship). He wrote his "Enquiries" (Greek – Historia; English – (The) Histories) in around 440-430 BC, trying to trace the origins of the Greco-Persian Wars, which would still have been relatively recent history (the wars finally ending in 449 BC).[2] Herodotus's approach was entirely novel, and at least in Western society, he does seem to have invented 'history' as we know it.[2] As Holland has it:

"For the first time, a chronicler set himself to trace the origins of a conflict not to a past so remote so as to be utterly fabulous, nor to the whims and wishes of some god, nor to a people's claim to manifest destiny, but rather explanations he could verify personally."[2]

Many subsequent ancient historians, despite following in his footsteps, derided Herodotus, starting with Thucydides.[3] Nevertheless Thucydides chose to begin his history where Herodotus left off (at the Siege of Sestos), and must therefore have felt that Herodotus had done a reasonable job of summarising the preceding history. Plutarch criticised Herodotus in his essay "On The Malignity of Herodotus", describing Herodotus as "Philobarbaros" (barbarian-lover), for not being pro-Greek enough. This actually suggests that Herodotus might have done a reasonable job of being even-handed.[4] A negative view of Herodotus was passed on Renaissance Europe, though he remained well read.[5] However, since the 19th century his reputation has been dramatically rehabilitated by archaeological finds which have repeatedly confirmed his version of events.[6] The prevailing modern view is perhaps that Herodotus generally did a remarkable job in his Historia, but that some of his specific details (particularly troop numbers and dates) should be viewed with skepticism.[6] However, there are still some historians who believe Herodotus made up much of his story.[7]

The Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus, writing in the 1st century BC in his Bibliotheca Historica, also provides an account of the Greco-Persian wars, partially derived from the earlier Greek historian Ephorus. This account is fairly consistent with Herodotus's.[8] The Greco-Persian wars are also described in less detail by a number of other ancient historians including Plutarch, Ctesias of Cnidus, and are alluded by other authors, such as the playwright Aeschylus. Archaeological evidence, such as the Serpent Column, also supports some of Herodotus's specific claims.[9]

[edit] Background

The first Persian invasion of Greece had its immediate roots in the Ionian Revolt, the earliest phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. However, it was also the result of the longer-term interaction between the Greeks and Persians. In 500 BC the Persian Empire was still relatively young and highly expansionistic, but prone to revolts amongst its subject peoples.[10][11][12] Moreover, the Persian king Darius was a usurper, and had spent considerable time extinguishing revolts against his rule.[10] Even before the Ionian Revolt, Darius had begun to expand the Empire into Europe, subjugating Thrace, and forcing Macedon to become allied to Persia. Attempts at further expansion into the politcally fractious world of Ancient Greece may have been inevitable.[11] However, the Ionian Revolt had directly threatened the integrity of the Persian empire, and the states of mainland Greece remained a potential menace to its future stability.[13] Darius thus resolved to subjugate and pacify Greece and the Aegean, and to punish those involved in the Ionian Revolt. [13][14]

The Ionian revolt had begun with an unsuccessful expedition against Naxos, a joint venture between the Persian satrap Artaphernes and the Miletus tyrant Aristagoras.[15] In the aftermath, Artaphernes decided to remove Aristagoras from power, but before he could do so, Aristagoras abdicated, and declared Miletus a democracy.[15] The other Ionian cities followed suit, ejecting their Persian-appointed tyrants, and declaring themselves democracies.[15][16] Artistagoras then appealed to the states of Mainland Greece for support, but only Athens and Eretria offered to send troops.[17]

The involvement of Athens in the Ionian Revolt arose from a complex set of circumstances, beginning with the establishment of the Athenian Democracy in the late 6th century BC.[17] In 510 BC, with the aid of Cleomenes I, King of Sparta, the Athenian people had expelled Hippias, the tyrant ruler of Athens.[18] With Hippias's father Peisistratus, the family had ruled for 36 out of the previous 50 years and fully intended to continue Hippias's rule.[18] Hippias fled to Sardis to the court of the Persian satrap, Artaphernes and promised control of Athens to the Persians if they were to help restore him.[19] In the meantime, Cleomenes helped install a pro-Spartan tyranny under Isagoras in Athens, in opposition to Cleisthenes, the leader of the traditionally powerful Alcmaeonidae family, who considered themselves the natural heirs to the rule of Athens.[20] In a daring response, Cleisthenes proposed to the Athenian people that he would establish a 'democracy' in Athens, much to the horror of the rest of the aristocracy. Cleisthenes's reasons for suggesting such a radical course of action, which would remove much of his own family's power, are unclear; perhaps he perceived that days of aristocratic rule were coming to an end anyway; certainly he wished to prevent Athens becoming a puppet of Sparta by whatever means necessary.[20] However, as a result of this proposal, Cleisthenes and his family were exiled from Athens, in addition to other dissenting elements, by Isagoras. Having been promised democracy however, the Athenian people seized the moment and revolted, expelling Cleomenes and Isogoras.[21] Cleisthenes was thus restored to Athens (507 BC), and at breakneck speed began to establish democratic government. The establishment of democracy revolutionised Athens, which henceforth became one of the leading cities in Greece.[21] The new found freedom and self-governance of the Athenians meant that they were thereafter exceptionally hostile to the return of the tyranny of Hippias, or any form of outside subjugation; by Sparta, Persia or anyone else.[21]

Cleomenes, unsurprisingly, was not pleased with events, and marched on Athens with the Spartan army.[22] Cleomenes's attempts to restore Isagoras to Athens ended in a debacle, but fearing the worst, the Athenians had by this point already sent an embassy to Artaphernes in Sardis, to request aid from the Persian Empire.[23] Artaphernes requested that the Athenians give him a 'earth and water', a traditional token of submission, which the Athenian ambassadors acquiesced to.[23] However, they were severely censured for this when they returned to Athens.[23] At some point later Cleomenes instigated a plot to restore Hippias to the rule of Athens. This failed and Hippias again fled to Sardis and tried to persuade the Persians to subjugate Athens.[24] The Athenians dispatched ambassadors to Artaphernes to dissuade him from taking action, but Artaphernes merely instructed the Athenians to take Hippias back as tyrant.[17] Needless to say, the Athenians balked at this, and resolved instead to be openly at war with Persia.[24] Having thus become the enemy of Persia, Athens was already in a position to support the Ionian cities when they began their revolt.[17] The fact that the Ionian democracies was inspired by the example of Athens no doubt further persuaded the Athenians to support the Ionian Revolt; especially since the cities of Ionia were (supposedly) originally Athenian colonies.[17]

The Athenians and Eretrians sent a task force of 25 triremes to Asia Minor to aid the revolt.[25] Whilst there, the Greek army surprised and outmaneuvered Artaphernes, marching to Sardis and there burning the lower city[26]. However, this was as much as the Greeks achieved, and they were then pursued back to the coast by Persian horsemen, losing many men in the process. Despite the fact that their actions were ultimately fruitless, the Eretrians and in particular the Athenians had earned Darius's lasting enmity, and he vowed to punish both cities [27]. The Persian naval victory at the Battle of Lade (494 BC) all but ended the Ionian Revolt, and by 493 BC, the last hold-outs were vanquished by the Persian fleet.[28] The revolt was used as an opportunity by Darius to extend the empire's border to the islands of the East Aegean[29] and the Propontis, which had not been part of the Persian dominions before.[30] The completion of the pacification of Ionia allowed the Persians to begin planning their next moves; to extinguish the threat to the empire from Greece, and to punish Athens and Eretria.[31]

In 492 BC, once the Ionian Revolt had finally been crushed, Darius dispatched an expedition to Greece under the command of his son-in-law, Mardonius. Mardonius re-conquered Thrace and compelled Alexander I of Macedon to make Macedon a client kingdom to Persia, before the wrecking of his fleet brought a premature end to the campaign.[32] However in 490 BC, following up the successes of the previous campaign, Darius decided to send a maritime expedition led by Artaphernes, (son of the satrap to whom Hippias had fled) and Datis, a Median admiral. Mardonius had been injured in the prior campaign and had fallen out of favor. The expedition was intended to bring the Cyclades into the Persian empire, to punish Naxos (which had resisted a Persian assault in 499 BC) and then to head to Greece to force Eretria and Athens to submit to Darius or be destroyed.[33] After island hopping across the Aegean, including successfully attacking Naxos, the Persian task force arrived off Euboea in mid summer. The Persians then proceeded to besiege, capture and burn Eretria. They then headed south down the coast of Attica, en route to complete the final objective of the campaign - to punish Athens.

[edit] Prelude

The Persians sailed down the coast of Attica, and landed at the bay of Marathon, roughly 25 miles (40 km) from Athens, on the advice of the exiled Athenian tyrant Hippias (who had accompanied the expedition).[34] Under the guidance of Miltiades, the Athenian general with the greatest experience of fighting the Persians, the Athenian army marched quickly to block the two exits from the plain of Marathon, and prevent the Persians moving inland.[35][36] At the same time, Athens's greatest runner, Pheidippides (or Philippides in some accounts) had been sent to Sparta to request that the Spartan army march to the aid of Athens.[37] Pheidippides arrived during the festival of Carneia, a sacrosanct period of peace, and was informed that the Spartan army could not march to war until the full moon rose; Athens could not expect reinforcement for at least ten days.[35] The Athenians would have to hold out at Marathon for the time being, although they were reinforced by a contingent of hoplites from Plataea; a gesture which did much to steady the nerves of the Athenians.[35]

For approximately five days the armies therefore confronted each other across the plain of Marathon, in stalemate.[35] The flanks of the Athenian camp was protected either by a grove of trees, or an abbatis of stakes (depending on the exact reading).[38][39] Since every day brought the arrival of the Spartans closer, the delay worked in favor of the Athenians.[35] There were ten Athenian strategoi (generals) at Marathon, elected by each of the ten tribes that the Athenians were divided into; Miltiades was one of these.[40] In addition, in overall charge, was the War-Archon (polemarch), Callimachus, who had been elected by the whole citizen body.[41] Herodotus suggests that command rotated between the strategoi, each taking in turn a day to command the army.[42] He further suggests that each strategos, on his day in command, instead deferred to Miltiades.[42] In Herodotus's account, Miltiades is keen to attack the Persians (despite knowing that the Spartans are coming to aid the Athenians), but strangely, chooses to wait until his actual day of command to attack.[42] This passage is undoubtedly problematic; the Athenians had little to gain by attacking before the Spartans arrived,[43] and there is no real evidence of this rotating generalship.[44] There does, however, seem to have been a delay between the Athenian arrival at Marathon, and the battle; Herodotus, who evidently believed that Miltiades was eager to attack, may have made a mistake whilst seeking to explain this delay.[44]

As is discussed below, the reason for the delay was probably simply that neither the Athenians nor the Persians were willing to risk battle initially.[45][43] This then raises the question of why the battle occurred when it did. Herodotus explicitly tells us that the Greeks attacked the Persians (and the other sources confirm this), but it is not clear why they did this before the arrival of the Spartans.[43] There are two main theories to explain this.[43]

The first theory is that the Persian cavalry became absent from Marathon, and that the Greeks moved to take advantage of this by attacking. This theory is based on the absence of any mention of cavalry in Herodotus's account of the battle, and an entry in the Suda dictionary.[43] The entry χωρίς ἰππεῖς ("without cavalry") is explained thus:

"The cavalry left. When Datis surrendered and was ready for retreat, the Ionians climbed the trees and gave the Athenians the signal that the cavalry had left. And when Miltiades realized that, he attacked and thus won. From there comes the above-mentioned quote, which is used when someone breaks ranks before battle"[46]

There are many variations of this theory, but perhaps the most prevalent is that the cavalry was re-embarked on the ships, and were to be sent by sea to attack (undefended) Athens in the rear, whilst the rest of the Persian pinned down the Athenian army at Marathon.[35] This theory therefore utilises Herodotus's suggestion that after Marathon, the Persian army re-embarked and tried to sail round Cape Sounion to attack Athens directly;[47] however, according to the first theory this attempt would have occured before the battle (and indeed have triggered the battle).[45]

The second theory is simply that the battle occurred because the Persians finally moved to attack the Athenians.[43] Although this theory has the Persians moving to the strategic offensive, this can be reconciled with the traditional account of the Athenians attacking the Persians by assuming that, seeing the Persians advancing, the Athenians took the tactical offensive, and attacked them.[43] Obviously, it cannot be firmly established which theory (if either) is correct. However, both theories imply that there was some kind of Persian activity which occurred on or about the fifth day which ultimately triggered the battle.[43]

[edit] Date of the battle

Herodotus mentions for several events a date in the lunisolar calendar, of which each Greek city-state used a variant. Astronomical computation allows us to derive an absolute date in the proleptic Julian calendar which is much used by historians as the chronological frame. August Böckh in 1855 concluded that the battle took place on September 12, 490 BC in the Julian calendar, and this is the conventionally accepted date.[48] However, this depends on when exactly the Spartans held their festival and it is possible that the Spartan calendar was one month ahead of that of Athens. In that case the battle took place on August 12, 490 BC.[48]

[edit] Opposing forces

[edit] Athenians

Herodotus does not give a figure for the size of the Athenian army. However, Cornelius Nepos, Pausanias and Plutarch all give the figure of 9,000 Athenians and 1,000 Plateans;[49][50][51] while Justin suggests that there were 10,000 Athenians and 1,000 Plataeans.[52] These numbers are highly comparable to the number of troops Herodotus says that the Athenians and Plataeans sent to the Battle of Plataea 11 years later.[53] Pausanias noticed on the monument to the battle the names of former slaves who were freed in exchange for military services.[54] Modern historians generally accept these numbers as reasonable.[55][35]

[edit] Persians

- For a full discussion of the size of the Persian invasion force, see First Persian invasion of Greece

According to Herodotus, the fleet sent by Darius consisted of 600 triremes.[56] Herodotus does not estimate the size of the Persian army, only saying that they were a "large infantry that was well packed".[57] Among ancient sources, the poet Simonides, another near-contemporary, says the campaign force numbered 200,000; while a later writer, the Roman Cornelius Nepos estimates 200,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, of which only 100,000 fought in the battle, while the rest were loaded into the fleet that was rounding Cape Sounion;[58] Plutarch[59] and Pausanias[60] both independently give 300,000, as does the Suda dictionary.[61] Plato and Lysias assert 500,000;[62][63] and Justinus 600,000.[64]

Modern historians have proposed wide ranging numbers for the infantry, from 20,000–100,000 with a consensus of perhaps 25,000;[65][66][67][68] estimates for the cavalry are in the range of 1,000.[69]

[edit] Strategic and tactical considerations

From a strategic point of view, the Athenians had some disadvantages at Marathon. In order to face the Persians in battle, the Athenians had had to summon all available hoplites;[35] and even then they were still probably outnumbered at least 2 to 1.[39] Furthermore, raising such a large army had denuded Athens of defenders, and thus any secondary attack in the Athenian rear would cut the army off from the city; and any direct attack on the city could not be defended against.[45] Still further, defeat at Marathon would mean the complete defeat of Athens, since no other Athenian army existed. The Athenian strategy was therefore to keep the Persian army pinned down at Marathon, blocking both exits from the plain, and thus preventing themselves from being outmanoeuvred.[35] However, these disadvatages were balanced by some advantages. The Athenians initially had no need to seek battle, since they had managed to confine the Persians to the plain of Marathon. Furthermore, time worked in their favour, as every day brought the arrival of the Spartans closer.[43][35] Having everything to lose by attacking, and much to gain by not attacking, the Athenians remained on the defensive in the run up to the battle.[43] Tactically, hoplites were vulnerable to attacks by cavalry, and since the Persians had substantial numbers of cavalry, this made any offensive manouever by the Athenians even more of a risk, and thus reinforced the defensive strategy of the Athenians.[45]

The Persian strategy, on the other hand, was probably principally determined by tactical considerations. The Persian infantry was evidently lightly armoured, and no match for hoplites in a head-on confrontation (as would be demonstrated at the later battles of Thermopylae and Plataea.[70] Since the Athenians seem to have taken up a strong defensive position at Marathon, the Persian hesitance was probably a reluctance to attack the Athenians head-on.[45]

Whatever event eventually triggered the battle, it obviously altered the strategic or tactical balance sufficiently to induce the Athenians to attack the Persians. If the first theory is correct (see above), then the absence of cavalry removed the main Athenian tactical disadvantage, and the threat of being outflanked made it imperative to attack.[45] Conversely, if the second theory is correct, then the Athenians were merely reacting to the Persians attacking them.[43] Since the Persian force obviously contained a high proportion of missile troops, a static defensive position would made little sense for the Athenians;[71] the strength of the hoplite was in the melee, and the sooner that could be brought about, the better, from the Athenian point of view.[70] If the second theory is correct, this raises the further question of why the Persians, having hesistated for several days, then attacked. There may have been several strategic reasons for this; perhaps they were aware (or suspected) that the Athenians were expecting reinforcements.[43] Alternatively, since they may have felt the need to force some kind of victory - they could hardly remain at Marathon indefinitely.[43]

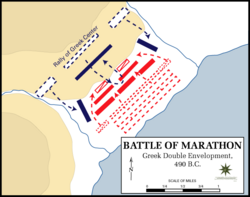

[edit] Battle

The distance between the two armies at the point of battle had narrowed to "a distance not less than 8 stadia" or about 1,500 meters.[72] Miltiades ordered the two tribes that were forming the center of the Greek formation, the Leontis tribe led by Themistocles and the Antiochis tribe led by Aristides, to be arranged in the depth of 4 ranks while the rest of the tribes at their flanks were in ranks of 8.[73][74] Some modern commentators have suggested this was a deliberate ploy to encourage a double envelopment of the Persian centre. However, this supposes a level of training that the Greeks did not possess, and that the Greek commanders thought in the same way as modern commanders.[75] There is little evidence for any such tactical thinking in Greek battles until Leuctra in 371 BC.[76] It is therefore probable that this arrangement was made, possibly at the last moment, so that the Athenian line was as long as the Persian line, and would not therefore be outflanked.[77][45]

When the Athenian line was ready, according to one source, the simple signal to advance was given by Miltiades: "At them".[45] Herodotus implies the Athenians ran the whole distance to the Persian lines, shouting their ululating war cry, "Ελελευ! Ελελευ!" ("Eleleu! Eleleu!").[72] It is doubtful that the Athenians ran the whole distance; in full armour this would be very difficult.[78] More likely, they marched until they reached the limit of the archers' effectiveness, the "beaten zone", (roughly 200 meters), and then broke into a run towards their enemy.[78] Herodotus suggests that this was the first time a Greek army ran into battle in this way; this was probably because it was the first time that a Greek army had faced an enemy composed primarily of missile troops.[78] All this was evidently much to the surprise of the Persians; "in their minds they charged the Athenians with madness which must be fatal, seeing that they were few and yet were pressing forwards at a run, having neither cavalry nor archers".[79] Indeed, based on their previous experience of the Greeks, the Persians might be excused for this; Herodotus tells us that the Athenians at Marathon were "first to endure looking at Median dress and men wearing it, for up until then just hearing the name of the Medes caused the Hellenes to panic".[72] Passing through the hail of arrows launched by the Persian army, protected for the most part by their armour, the Greek line finally collided with the enemy army. Holland provides an evocative description:

"The enemy directly in their path...realised to their horror that [the Athenians], far from providing the easy pickings for their bowmen, as they had first imagined, were not going to be halted...The impact was devastating. The Athenians had honed their style of fighting in combat with other phalanxes, wooden shields smashing against wooden shields, iron spear tips clattering against breastplates of bronze...in those first terrible seconds of collision, there was nothing but a pulverizing crash of metal into flesh and bone; then the rolling of the Athenian tide over men wearing, at most, quilted jerkins for protection..."[80]

The Athenian wings quickly routed the inferior Persian levies on the flanks, before turning inwards to surround the Persian centre, which had been more successful against the thin Greek centre.[81] The battle ended when the Persian centre then broke in panic towards their ships, pursued by the Greeks.[81]. Some, unaware of the local terrain, ran towards the swamps where unknown numbers drowned.[82][83] The Athenians pursued the Persians back to their ships, and managed to capture 7, though the majority were able to successfully launch.[84][47] Herodotus recounts the story that Cynegirus, brother of the playwright Aeschylus, who was also among the fighters, charged into the sea, grabbed one Persian trireme, and started pulling it towards shore. A member of the crew saw him, cut off his hand, and Cynegirus died.[84]

Herodotus records that 6,400 Persian bodies were counted on the battlefield, and it is unknown how many more perished in the swamps.[85] The Athenians lost 192 men and the Plataeans 11.[85] Among the dead was the war archon Callimachus and the general Stesilaos.[84]

[edit] Aftermath

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Herodotus says that the Persian fleet sailed around Cape Sunium to attack Athens directly.[47] As has been discussed above, some modern historians place this attempt just before the battle. Either way, the Athenians evidently realised that their city was still under threat, and marched as quickly as possible back to Athens.[86] The two tribes which had been in the centre of the Athenian line, stayed to guard the battlefield, under the command of Aristides.[87] The Athenians arrived in time to prevent the Persians from securing a landing. Seeing that the opportunity was lost, the Persians turned about and returned to Asia.[86] Connected with this episode, Herodotus recounts a rumour that this manoeuver by the Persians had been planned in conjuction with the Alcmonidae, the prominent Athenian aristocratic family, and that a "shield-signal" had been given after the battle.[47] Although many interpretations of this have been offered, it is impossible to to tell whether this was true, and if so, what exactly the signal meant.[88] On the next day, the Spartan army arrived at Marathon, having covered the 220 kilometers (140 miles) in only three days. The Spartans toured the battlefield at Marathon, and agreed that the Athenians had won a great victory.[89]

The dead of Marathon were awarded by the Athenians the special honor of being the only ones who were buried where they died instead of the main Athenian cemetery at Keramikos.[90] On the tomb of the Athenians this epigram composed by Simonides was written:

- Ελλήνων προμαχούντες Αθηναίοι Μαραθώνι

- χρυσοφόρων Μήδων εστόρεσαν δύναμιν

- The Athenians, as defenders of the Hellenes, in Marathon

- destroyed the might of the golden-dressed Medes[91]

In the meanwhile, Darius began raising a huge new army with which he meant to completely subjugate Greece; however, in 486 BC, his Egyptian subjects revolted, indefinitely postponing any Greek expedition.[92] Darius then died whilst preparing to march on Egypt, and the throne of Persia passed to his son Xerxes I.[93] Xerxes crushed the Egyptian revolt, and very quickly re-started the preparations for the invasion of Greece.[94] The epic second Persian invasion of Greece finally began in 480 BC, and the Persians met with initial success at the battles of Thermopylae and Artemisium.[95] However, defeat at the Battle of Salamis would be the turning point in the campaign,[96] and the next year the expedition was ended by the decisive Greek victory at the Battle of Plataea.[97]

[edit] Significance

The defeat at Marathon barely touched the enormous resources of the Persian empire, yet for the Greeks it was an enormously significant victory. It was the first time the Greeks had beaten the Persians, and showed them that the Persians were not invincible, and that resistance, rather than subjugation, was possible.[98]

The battle was a defining moment for the young Athenian democracy, showing what might be achieved through unity and self-belief; indeed, the battle effectively marks the start of a 'golden age' for Athens [99]. This was also applicable to Greece as a whole; "their victory endowed the Greeks with a faith in their destiny that was to endure for three centuries, during which western culture was born".[2][100] John Stuart Mill's famous opinion was that "the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in British history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings".[101] It seems that the Athenian playwright Aeschylus considered his participation at Marathon to be his greatest achievement in life (rather than his plays) since on his gravestone there was the following epigram:

- Αἰσχύλον Εὐφορίωνος Ἀθηναῖον τόδε κεύθει

- μνῆμα καταφθίμενον πυροφόροιο Γέλας·

- ἀλκὴν δ’ εὐδόκιμον Μαραθώνιον ἄλσος ἂν εἴποι

- καὶ βαρυχαιτήεις Μῆδος ἐπιστάμενος

- This tomb the dust of Aeschylus doth hide,

- Euphorion's son and fruitful Gela's pride

- How tried his valor, Marathon may tell

- And long-haired Medes, who knew it all too well.[102]

Militarily, a major lesson for the Greeks was the potential of the hoplite phalanx. This style had developed during internecine warfare amongst the Greeks; since each city-state fought in the same way, the advantages and disadvantages of the hoplite phalanx had not been obvious.[80] Marathon was the first time a phalanx faced more lightly-armed troops, and revealed how effective the hoplites could be in battle.[80] The phalanx formation was still vulnerable to cavalry (the cause of much caution by the Greek forces at the Battle of Plataea), but used in the right circumstances, it was now shown to be a potentially devastating weapon.[103]

[edit] Legacy

[edit] Legends associated with the battle

The most famous legend associated with Marathon is that of the runner Pheidippides/Philippides bringing news to Athens of the battle, which is described below.

Pheidippides' run to Sparta to bring aid has other legends associated with it. Herodotus mentions that Pheidippides was visited by the god Pan on his way to Sparta (or perhaps on his return journey).[35] Pan asked why the Athenians did not honor him and Pheidippides promised that they would do so from then on. After the battle, a temple was built to him, and a sacrifice was annually offered.[104]

Similarly, after the victory the festival of 'Agroteras Thusia', ('Thusia' means sacrifice) was held at Agrae near Athens, in honor of Artemis Agrotera. This was in fulfillment of a vow made by the city before the battle, to offer in sacrifice a number of goats equal to that of the Persians slain in the conflict. The number was so great, it was decided to offer 500 goats yearly until the number was filled. Xenophon notes that at his time, 90 years after the battle, goats were still offered yearly.[105][106][107][108]

Plutarch mentions that the Athenians saw Theseus, the mythical hero of Athens leading the army in full battle gear in the charge against the Persians,[109] and indeed he was depicted in the mural of the Poikele Stoa fighting for the Athenians, along with the twelve Olympian gods and other heroes.[110] Pausanias also tells us that:

"They say too that there chanced to be present in the battle a man of rustic appearance and dress. Having slaughtered many of the foreigners with a plough he was seen no more after the engagement. When the Athenians made enquiries at the oracle the god merely ordered them to honor Echetlaeus (he of the Plough-tail) as a hero."[111]

Another tale from the conflict is of the dog of Marathon. Aelian relates that one hoplite brought his dog to the Athenian encampment. The dog followed his master to battle and attacked the Persians at his master's side. He also informs us that this dog is depicted in the mural of the Poikile Stoa.[112]

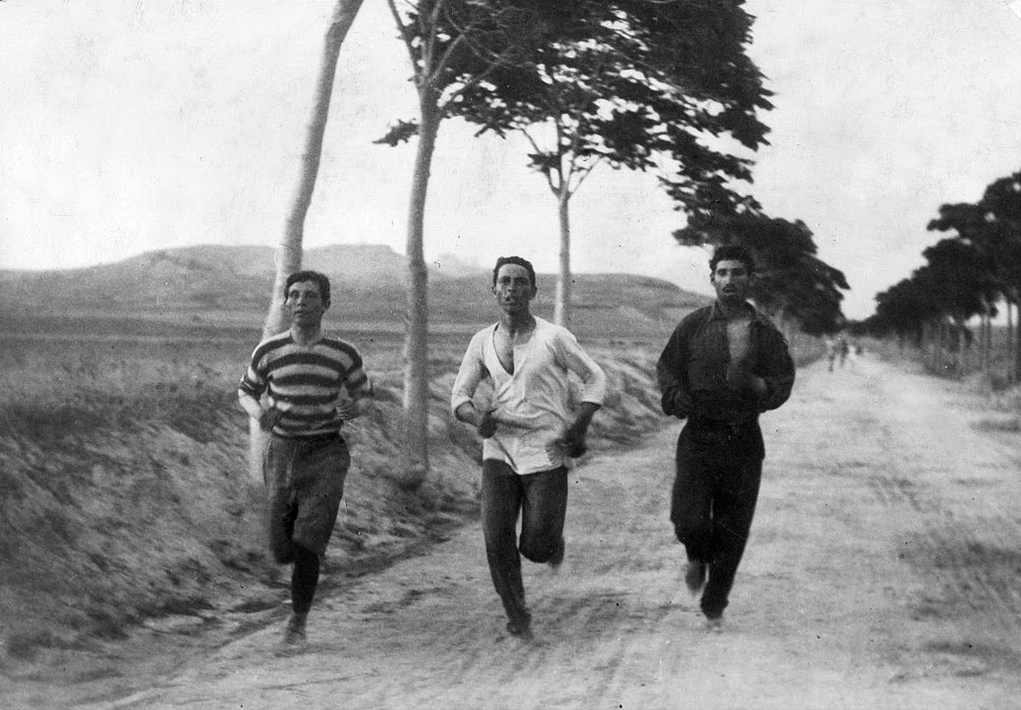

[edit] Marathon run

According to Herodotus, an Athenian runner named Pheidippides was sent to run from Athens to Sparta to ask for assistance before the battle, covering the distance of 140 miles in two days. [113] Then, following the battle, the Athenian army marched the 25 or so miles back to Athens at a very high pace (considering the quantity of armour, and the fatigue after the battle), in order to head off the Persians force sailing around Cape Sounion. They arrived back in the late afternoon, in time to see the Persian ships turn away from Athens, thus completing the Athenian victory [114].

Later, in popular imagination, these two events became confused with each other, leading to a legendary, but inaccurate version of events. This myth has Pheidippides running from Marathon to Athens after the battle, to announce the Greek victory with the word "Nenikēkamen!" (Attic: Νενικήκαμεν (We were victorious!)), whereupon he promptly died of exhaustion. Most accounts incorrectly attribute this story to Herodotus; however, the story first appears in Plutarch's On the Glory of Athens in the 1st century AD, who quotes from Heracleides of Pontus's lost work, giving the runner's name as either Thersipus of Erchius or Eucles.[115] Lucian of Samosata (2nd century AD) gives the same story but names the runner Philippides (not Pheidippides).[116] It should be noted that in some medieval codices of Herodotus the name of the runner between Athens and Sparta before the battle is given as Philippides and in a few modern editions this name is preferred.[117]

When the idea of a modern Olympics became a reality at the end of the 19th century, the initiators and organizers were looking for a great popularizing event, recalling the ancient glory of Greece.[118] The idea of organizing a 'marathon race' came from Michel Bréal, who wanted the event to feature in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 in Athens. This idea was heavily supported by Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics, as well as the Greeks.[118] This would echo the legendary version of events, with the competitors running from Marathon to Athens. So popular was this event that it quickly caught on, becoming a fixture at the Olympic games, with major cities staging their own annual events[118]. The distance eventually became fixed at 26 miles (42 km) and 325 yards (297 m), though for the first years it was variable, being around 25 miles (40 km) - the approximate distance from Marathon to Athens.[118]

[edit] References

- ^ Cicero, On the Laws I, 5

- ^ a b c d Holland, pp xvi–xvii

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, e.g. I, 22

- ^ Holland, p xxiv

- ^ David Pipes. "Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies". http://www.loyno.edu/history/journal/1998-9/Pipes.htm. Retrieved on 2008-01-18.

- ^ a b Holland, p377

- ^ Fehling, pp1–277.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca Historica, XI, 28–34

- ^ Note to Herodotus IX, 81

- ^ a b Holland, p47–55

- ^ a b Holland, p58–62

- ^ Holland, p203

- ^ a b Holland, 171–178

- ^ Herodotus V, 105

- ^ a b c Holland, p154–157

- ^ Herodotus V, 97

- ^ a b c d e Holland, p157–161

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 65

- ^ Herodotus V, 96

- ^ a b Holland, pp131–132

- ^ a b c Holland, pp133-138

- ^ Holland, p136–138

- ^ a b c Holland, p142

- ^ a b Herodotus V, 96

- ^ Herodotus V, 99

- ^ Holland, p160

- ^ Holland, p168

- ^ Holland, p176

- ^ Herodotus VI, 31

- ^ Herodotus VI, 33

- ^ Holland, p177–178

- ^ Herodotus VI, 44

- ^ Herodotus VI, 94

- ^ Herodotus VI, 102

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Holland, pp187–190

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades, IV

- ^ Herodotus VI, 105

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades, VI

- ^ a b Lazenby, p56

- ^ Herodotus VI, 103

- ^ Herodotus VI, 109

- ^ a b c Herodotus VI, 110

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Lazenby, pp59–62

- ^ a b Lazenby, p57–59

- ^ a b c d e f g h Holland, pp191–195

- ^ Suda, entry Without cavalry

- ^ a b c d Herodotus VI, 115

- ^ a b D.W. Olson et al., pp34–41

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades V

- ^ Pausanias X, 20

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia, 305 B

- ^ Justin II, 9

- ^ Herodotus IX, 28

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece I, 32

- ^ Lazenby, p54

- ^ Herodotus VI, 95

- ^ Herodotus VI, 94

- ^ Cornelius Nepos, Miltiades, IV

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia, 305 B

- ^ Pausanias IV, 22

- ^ Suda, entry Hippias

- ^ Plato, Menexenus, 240 A

- ^ Lysias, Funeral Oration, 21

- ^ Justinus II, 9

- ^ Davis, pp9–13

- ^ Holland, p390

- ^ Lloyd, p164

- ^ Green, The Greco-Persian Wars, p90

- ^ Lazenby, p46

- ^ a b Lazenby, p256

- ^ Lazenby, p67

- ^ a b c Herodotus VI, 112

- ^ Plutarch, Aristides, V

- ^ Herodotus VI, 111

- ^ Lazenby, p250

- ^ Lazenby, p258

- ^ Lazenby, p64

- ^ a b c Lazenby, p66–69

- ^ Herodotus VI, 110 [1]

- ^ a b c Holland, pp194-197

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 113

- ^ Pausanias I, 32

- ^ Lazenby, p71–71

- ^ a b c Herodotus VI, 114 [2]

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 117

- ^ a b Herodotus VI, 116

- ^ Holland, p218

- ^ Lazenby, pp72–73

- ^ Herodotus VI, 120

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War II, 34

- ^ translation by Major General Dimitris Gedeon, HEA

- ^ Holland, p203

- ^ Holland, pp206–207

- ^ Holland, pp208–211

- ^ Lazenby, p151

- ^ Lazenby, p197

- ^ Holland, pp350–355

- ^ Holland, p201

- ^ Holland, p138

- ^ Fuller, pp11–32

- ^ Powell et al., 2001

- ^ Anthologiae Graecae Appendix, vol. 3, Epigramma sepulcrale p17

- ^ Holland, pp344–352

- ^ Herodotus VI, 105

- ^ Plutarch, On the Malice of Herodotus, 26

- ^ Xenophon, Anabasis III, 2

- ^ Aelian, Varia Historia II, 25

- ^ Aristophanes, The Knights, 660

- ^ Plutarch, Theseus, 35

- ^ Pausanias I, 15

- ^ Pausanias I, 32

- ^ Aelian, On the Nature of Animals VII, 38

- ^ Herodotus VI, 105–106

- ^ Holland, p198

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia, 347C

- ^ Lucian, III

- ^ Lazenby, p52

- ^ a b c d AIMS. "Marathon History". http://aimsworldrunning.org/marathon_history.htm. Retrieved on 2008-10-15.

[edit] Sources

[edit] Primary sources

- Herodotus, The Histories

- Thucydides, History of The Peloponnesian Wars

- Diodorus Siculus, Library

- Lysias, Funeral Oration

- Plato, Menexenus

- Xenophon Anabasis

- Aristotle, The Athenian Constitution

- Aristophanes, The Knights

- Cornelius Nepos Lives of the Eminent Commanders (Miltiades)

- Plutarch Parallel Lives (Aristides, Themistocles, Theseus), On the Malice of Herodotus

- Lucian, Mistakes in Greeting

- Pausanias, Description of Greece

- Claudius Aelianus Various history & On the Nature of Animals

- Marcus Junianus Justinus Epitome of the Phillipic History of Pompeius Trogus

- Photius, Bibliotheca or Myriobiblon: Epitome of Persica by Ctesias

- Suda Dictionary

[edit] Secondary sources

- Green, Peter (1996). The Greco-Persian Wars. University of California Press. ISBN 0520203135.

- Holland, Tom (2006). Persian Fire: The First World Empire and the Battle for the West. Abacus. ISBN 0385513119.

- Lazenby, JF. The Defence of Greece 490–479 BC. Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1993 (ISBN 0-85668-591-7)

- Lloyd, Alan. Marathon:The Crucial Battle That Created Western Democracy. Souvenir Press, 2004. (ISBN 0-285-63688-X)

- Davis, Paul. 100 Decisive Battles. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 1-57607-075-1

- Powell J., Blakeley D.W., Powell, T. Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century, 1800-1914. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. ISBN 9780313304224

- Fuller, J.F.C. A Military History of the Western World. Funk & Wagnalls, 1954.

- Fehling, D. Herodotus and His "Sources": Citation, Invention, and Narrative Art. Translated by J.G. Howie. Leeds: Francis Cairns, 1989.

- Anthologiae Graecae Appendix, vol. 3, Epigramma sepulcrale

- D.W. Olson et al., "The Moon and the Marathon", Sky & Telescope Sep. 2004

- AIMS. "Marathon History". http://aimsworldrunning.org/marathon_history.htm. Retrieved on 2008-10-15.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Battle of Marathon |

- Battle of Marathon animated battle map by Jonathan Webb

- Livius, Battle of Marathon by Jona Lendering

- Black and white photo-essay of Marathon

- "Battle of Marathon", Chapt. I of Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World from Marathon to Waterloo according to Edward Shepherd Creasy, 1851 (see also The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World at Project Gutenberg ).