Musical scale

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In music, a scale is a group of musical notes collected in ascending and descending order that provides material for or is used to conveniently represent part or all of a musical work including melody and/or harmony.[1] Scales are ordered in pitch or pitch class, with their ordering providing a measure of musical distance.

The distance between two successive notes in a scale is called a scale step.

Contents |

[edit] Background

Scales are typically listed from low to high. A scale is octave-repeating when its pattern of notes is the same in every octave. An octave-repeating scale can be represented as a circular arrangement of pitch classes, ordered by increasing (or decreasing) pitch class. For instance, the increasing C major scale is, C-D-E-F-G-A-B-[C], with the bracket indicating that the last note is an octave higher than the first note. Or C-B-A-G-F-E-D-[C], with the bracket indicating an octave lower than the first note in the scale.

This single scale can be manifested at many different pitch levels. For example a C major scale can be started at C4 (middle C; see scientific pitch notation) and ascending an octave to C5; or it could be started at C6, ascending an octave to C7.

Scales may be described according to the intervals they contain:

- for example: diatonic, chromatic, whole tone

or by the number of different pitch classes they contain:

- very common: pentatonic, hexatonic, heptatonic have five, six, and seven tone scales, respectively.

- used in prehistoric music: ditonic or two, tritonic or three, tetratonic or four

- used in jazz and modern classical music: octatonic or eight.

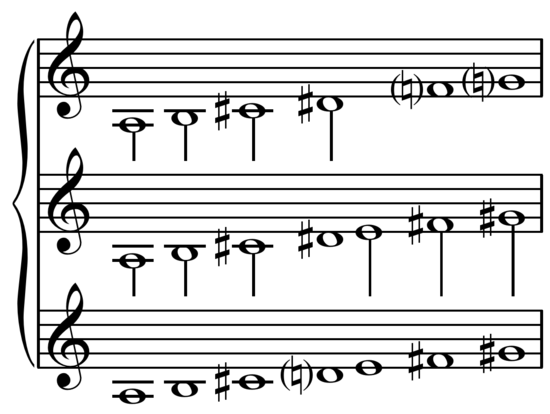

Scales can be abstracted from performance or composition. They are also often used precompositionally to guide or limit a composition. Explicit instruction in scales has been part of compositional training for many centuries. One or more scales may be used in a composition, such as in Claude Debussy's L'Isle Joyeuse. Below, the first scale is a whole tone scale, while the second and third scales are diatonic scales. All three are used in the opening pages of Debussy's piece.

[edit] Terminological note: scale versus mode

Musicians use the term "scale" in several incompatible senses. Sometimes the term refers to an ordered collection in which no element has been chosen as primary. Thus musicians will talk about the "white-note diatonic scale" or the "whole tone scale with three black notes." However, the term is sometimes used to mean "mode," indicating that an element of the scale has been chosen as most important ("the major scale starting on D"). The term "scale" is also used to refer to types of scales related by transposition. In this sense, musicians will talk about the diatonic scale, considering the C diatonic scale and G diatonic scale to be instances of a single, larger category. Consistency suggests distinguishing a "scale" (such as C or G diatonic) from "scale type" (the diatonic scale-type"). To avoid neologisms, however, we will follow traditional musical practice, using the term "scale" in both senses. Context should allow readers to distinguish between particular scales and the larger types to which they belong.

In addition, the term "scale" is used in psychoacoustics to refer to various ways of measuring distances between pitches. See bark scale and mel scale.

[edit] Scales in Western music

Scales in traditional Western music generally consist of seven notes and repeat at the octave. Notes in the commonly used scales (see just below) are separated by whole and half step intervals of tones and semitones. The harmonic minor scale includes a three-semitone step; the pentatonic includes two of these.

Western music in the Medieval and Renaissance periods (1100–1600) tends to use the white-note diatonic scale C-D-E-F-G-A-B. Accidentals are rare, and somewhat unsystematically used, often to avoid the tritone.

Music of the common practice periods (1600–1900) uses three types of scale:

- The diatonic scale (seven notes)

- The melodic and harmonic minor scales (seven notes)

These scales are used in all of their transpositions. The music of this period introduces modulation, which involves systematic changes from one scale to another. Modulation occurs in relatively conventionalized ways. For example, major-mode pieces typically begin in a "tonic" diatonic scale and modulate to the "dominant" scale a fifth above.

In the nineteenth and twentieth century, additional types of scales were explored:

- The chromatic scale (twelve notes)

- The whole tone scale (six notes)

- The pentatonic scale (five notes)

- The octatonic or diminished scales (eight notes)

A large — indeed, virtually endless — variety of other scales exists:

- The Phrygian dominant scales (actually, a mode of the harmonic minor scale)

- The Arabic scales

- The Hungarian minor scale

[edit] Naming the notes of a scale

In many musical circumstances, a specific note of the scale will be chosen as the "tonic" – the central and most stable note of the scale. Relative to a choice of tonic, the notes of a scale are often labeled with numbers recording how many scale steps above the tonic they are. For example, the notes of the C diatonic scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) can be labeled {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}, reflecting the choice of C as tonic. The term "scale degree" refers to these numerical labels. In the C diatonic scale, with C chosen as tonic, C is the first scale degree, D is the second scale degree, and so on.

Note that such labeling requires the choice of a "first" note; hence scale-degree labels are not intrinsic to the scale itself, but rather to its modes. For example, if we choose A as tonic, then we can label the notes of the C diatonic scale using A = 1, B = 2, C = 3, D = 4, and so on.

The scale degrees of a heptatonic (7-note) scale can also be named using the terms tonic, supertonic, mediant, subdominant, dominant, submediant, subtonic. If the subtonic is a semitone away from the tonic, then it is usually called the leading-tone (or leading-note); otherwise the leading-tone refers to the raised subtonic. Also commonly used is the (movable do) solfège naming convention in which each scale degree is given a syllable. In the major scale, the solfege syllables are: Do, Re, Mi, Fa, So (or Sol), La, Ti (or Si), Do (or Ut).

In naming the notes of a scale, it is customary that each scale degree be assigned its own letter name: for example, the A diatonic scale is written A - B - C♯ - D - E - F♯ - G♯ rather than A - B - D♭ - D - F♭ - E![]() - G♯. However, it is impossible to do this with scales containing more than seven notes.

- G♯. However, it is impossible to do this with scales containing more than seven notes.

Scales may also be identified by using a binary system of twelve zeros or ones to represent each of the twelve notes of 12 note equal temperament, assuming the tonic to be in the leftmost position. For example 101011010101 would represent C-D-E-F-G-A-B, which can be shown as the decimal number 2773. This system includes scales from 100000000000 (2048) to 111111111111 (4095), providing a total of 2048 possible unique scales containing from 1 to 12 notes.

Scales may also be shown as semitones (or fret positions) as e.g. 0 2 4 5 7 9 11 for C-D-E-F-G-A-B.

All these naming systems, except for heptatonic/diatonic interval naming, are restricted to scales for a 12 note octave division, not distinguishing sharps and flats.

[edit] Scalar transposition

One can transform musical patterns by moving every note in the pattern by a constant number of scale steps: thus, in the C major scale, the pattern C-D-E might be shifted up, or transposed, a single scale step to become D-E-F. This process is called "scalar transposition" and can often be found in musical sequences. Since the steps of a scale can have various sizes, this process introduces subtle melodic and harmonic variation into the music. This variation is what gives scalar music much of its complexity.

[edit] Non-Western scales

In Western music, scale notes are often separated by equally-tempered tones or semitones, creating twelve pitches per octave. Many other musical traditions employ scales that include other intervals or a different number of pitches. The origin within these scales lies within the derivation of the harmonic series. Musical intervals are complementary values of the harmonic overtones series[2]. All musical scales in the world are based on this system, except for the Western equal tempered which originally was based on those pitches as well, but was modified because of the evolution of Western Classical Music to the currently common used mathematical logarithmic scale. A common scale in Eastern music is the pentatonic scale, consisting of five tones. In the Middle Eastern Hejaz scale, there are some intervals of three semitones. Gamelan music uses a small variety of scales including Pélog and Sléndro, none including equally tempered intervals. Rāgas in Indian classical music often employ intervals smaller than a semitone [3]. Arabic music maqamat may use quarter tone intervals [4]. In both rāgas and maqamat, the distance between a note and an inflection (e.g., śruti) of that same note may be less than a semitone.

[edit] Indian musical scale

[edit] Microtonal scales

The term microtonal music usually refers to music with roots in traditional Western music that employs non-standard scales or scale intervals. Mexican composer Julián Carrillo created in the late 1800s one of the first microtonal scales which he called "Sonido 13", The composer Harry Partch made custom musical instruments to play compositions that employed a 43-note scale system, and the American jazz vibraphonist Emil Richards experimented with such scales in his 'Microtonal Blues Band' in the 1970s. Easley Blackwood has written several microtonal but equal-tempered compositions. John Cage, the American experimental composer, also created works for prepared piano which use varied, sometimes random, scales. Erv Wilson introduced concepts such as Combination Product Sets, Moments of Symmetry and golden horagrams, used by many modern composers. Microtonal scales are also used in traditional Indian Raga music, which has a variety of modes which are used not only as modes or scales but also as defining elements of the song, or raga.

[edit] See also

- Hexany (one of Erv Wilson's scales used by many composers)

[edit] Jazz and blues

Through the introduction of blue notes, jazz and blues employ scale intervals smaller than a semitone. The blue note is an interval that is technically neither major nor minor but "in the middle", giving it a characteristic flavour. For instance, in the key of E, the blue note would be either a note between G and G♯ or a note moving between both. In blues a pentatonic scale is often used. In jazz many different modes and scales are used, often within the same piece of music. Chromatic scales are common, especially in modern jazz.

[edit] Chords, patterns, and scalar transposition

As discussed above, musicians often utilize scales by shifting (transposing) a musical pattern by some constant number of scale steps. This process is known as scalar transposition.

The harmonies of traditional tonal music are constructed in this way. Western tonal chords are stacks of thirds, with or without accidentals, built above a particular scale degree, which is called the root of the harmony. Thus in a C diatonic scale: C D E F G A B, a three-note chord built on C will consist of the notes C-E-G. The same pattern, built on the note G, produces the chord G-B-D.

[edit] References

- ^ Benward & Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, Vol. I, p.25. Seventh Edition. ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Explanation of the origin of musical scales clarified by a string division method by Yuri Landman on furious.com

- ^ Burns 1998, 247

- ^ Zonis, 1973

[edit] Bibliography

- Burns, Edward M. 1998. "Intervals, Scales, and Tuning." In The Psychology of Music, second edition, edited by Diana Deutsch, 215–64. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-213564-4.

- Zonis [Mahler], Ellen. 1973. Classical Persian Music: An Introduction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[edit] External links

- Simple and accurate reference for all scales

- Wolfram Notes - hear and play musical scales

- ScaleCoding

- Database in .xls and FileMaker formats of all 2048 possible unique scales in 12 tone equal temperament + meantone alternatives.

- Barbieri, Patrizio. Enharmonic instruments and music, 1470-1900. (2008) Latina, Il Levante Libreria Editrice

- Java applet that lists all N-note scales, and lets you see & hear them in standard musical notation

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Musical scale |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Musical scales |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||