Caesar cipher

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The action of a Caesar cipher is to replace each plaintext letter with one a fixed number of places down the alphabet. This example is with a shift of three, so that a B in the plaintext becomes E in the ciphertext. |

|

| Detail | |

|---|---|

| Structure | substitution cipher |

| Best public cryptanalysis | |

| Susceptible to frequency analysis and brute force attacks. | |

In cryptography, a Caesar cipher, also known as a Caesar's cipher, the shift cipher, Caesar's code or Caesar shift, is one of the simplest and most widely known encryption techniques. It is a type of substitution cipher in which each letter in the plaintext is replaced by a letter some fixed number of positions down the alphabet. For example, with a shift of 3, A would be replaced by D, B would become E, and so on. The method is named after Julius Caesar, who used it to communicate with his generals.

The encryption step performed by a Caesar cipher is often incorporated as part of more complex schemes, such as the Vigenère cipher, and still has modern application in the ROT13 system. As with all single alphabet substitution ciphers, the Caesar cipher is easily broken and in practice offers essentially no communication security.

Contents |

[edit] Example

The transformation can be represented by aligning two alphabets; the cipher alphabet is the plain alphabet rotated left or right by some number of positions. For instance, here is a Caesar cipher using a left rotation of three places (the shift parameter, here 3, is used as the key):

Plain: ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ Cipher: DEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZABC

When encrypting, a person looks up each letter of the message in the "plain" line and writes down the corresponding letter in the "cipher" line. Deciphering is done in reverse.

Plaintext: the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog Ciphertext: WKH TXLFN EURZQ IRA MXPSV RYHU WKH ODCB GRJ

The encryption can also be represented using modular arithmetic by first transforming the letters into numbers, according to the scheme, A = 0, B = 1,..., Z = 25.[1] Encryption of a letter x by a shift n can be described mathematically as,[2]

Decryption is performed similarly,

(There are different definitions for the modulo operation. In the above, the result is in the range 0...25. I.e., if x+n or x-n are not in the range 0...25, we have to subtract or add 26.)

The replacement remains the same throughout the message, so the cipher is classed as a type of monoalphabetic substitution, as opposed to polyalphabetic substitution.

[edit] History and usage

The Caesar cipher is named after Julius Caesar, who, according to Suetonius, used it with a shift of three to protect messages of military significance. While Caesar's was the first recorded use of this scheme, other substitution ciphers are known to have been used earlier.

If he had anything confidential to say, he wrote it in cipher, that is, by so changing the order of the letters of the alphabet, that not a word could be made out. If anyone wishes to decipher these, and get at their meaning, he must substitute the fourth letter of the alphabet, namely D, for A, and so with the others.

His nephew, Augustus, also used the cipher, but with a right shift of one, and it did not wrap around to the beginning of the alphabet:

Whenever he wrote in cipher, he wrote B for A, C for B, and the rest of the letters on the same principle, using AA for X.

There is evidence that Julius Caesar used more complicated systems as well,[3] and one writer, Aulus Gellius, refers to a (now lost) treatise on his ciphers:

There is even a rather ingeniously written treatise by the grammarian Probus concerning the secret meaning of letters in the composition of Caesar's epistles.

—Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights 17.9.1–5

It is unknown how effective the Caesar cipher was at the time, but it is likely to have been reasonably secure, not least because most of Caesar's enemies would have been illiterate and others would have assumed that the messages were written in an unknown foreign language.[4] Assuming that an attacker could read the message, there is no record at that time of any techniques for the solution of simple substitution ciphers. The earliest surviving records date to the 9th century works of Al-Kindi in the Arab world with the discovery of frequency analysis.[5]

A Caesar cipher with a shift of one is used on the back of the Mezuzah to encrypt the names of God. This may be a holdover from an earlier time when Jewish people were not allowed to have Mezuzahs. The letters of the cryptogram themselves comprise a divine name which keeps the forces of evil in check.[6]

In the 19th century, the personal advertisements section in newspapers would sometimes be used to exchange messages encrypted using simple cipher schemes. Kahn (1967) describes instances of lovers engaging in secret communications enciphered using the Caesar cipher in The Times.[7] Even as late as 1915, the Caesar cipher was in use: the Russian army employed it as a replacement for more complicated ciphers which had proved to be too difficult for their troops to master; German and Austrian cryptanalysts had little difficulty in decrypting their messages.[8]

Caesar ciphers can be found today in children's toys such as secret decoder rings. A Caesar shift of thirteen is also performed in the ROT13 algorithm, a simple method of obfuscating text widely found in UNIX and used to obscure text (such as joke punchlines and story spoilers), but not used as a method of encryption.[9]

The Vigenère cipher uses a Caesar cipher with a different shift at each position in the text; the value of the shift is defined using a repeating keyword. If a single-use keyword is as long as the message and chosen randomly then this is a one-time pad cipher, unbreakable if the users maintain the keyword's secrecy. Keywords shorter than the message (e.g., "Complete Victory" used by the Confederacy during the American Civil War), introduce a cyclic pattern that might be detected with a statistically advanced version of frequency analysis.[10]

In April 2006, fugitive Mafia boss Bernardo Provenzano was captured in Sicily partly because of cryptanalysis of his messages written in a variation of the Caesar cipher. Provenzano's cipher used numbers, so that "A" would be written as "4", "B" as "5", and so on.[11]

[edit] Breaking the cipher

| Decryption shift |

Candidate plaintext |

|---|---|

| 0 | exxegoexsrgi |

| 1 | dwwdfndwrqfh |

| 2 | cvvcemcvqpeg |

| 3 | buubdlbupodf |

| 4 | attackatonce |

| 5 | zsszbjzsnmbd |

| 6 | yrryaiyrmlac |

| ... | |

| 23 | haahjrhavujl |

| 24 | gzzgiqgzutik |

| 25 | fyyfhpfytshj |

The Caesar cipher can be easily broken even in a ciphertext-only scenario. Two situations can be considered:

- an attacker knows (or guesses) that some sort of simple substitution cipher has been used, but not specifically that it is a Caesar scheme;

- an attacker knows that a Caesar cipher is in use, but does not know the shift value.

In the first case, the cipher can be broken using the same techniques as for a general simple substitution cipher, such as frequency analysis or pattern words.[12] While solving, it is likely that an attacker will quickly notice the regularity in the solution and deduce that a Caesar cipher is the specific algorithm employed.

In the second instance, breaking the scheme is even more straightforward. Since there are only a limited number of possible shifts (26 in English), they can each be tested in turn in a brute force attack.[13] One way to do this is to write out a snippet of the ciphertext in a table of all possible shifts[14] — a technique sometimes known as "completing the plain component".[15] The example given is for the ciphertext "EXXEGOEXSRGI"; the plaintext is instantly recognisable by eye at a shift of four. Another way of viewing this method is that, under each letter of the ciphertext, the entire alphabet is written out in reverse starting at that letter. This attack can be accelerated using a set of strips prepared with the alphabet written down them in reverse order. The strips are then aligned to form the ciphertext along one row, and the plaintext should appear in one of the other rows.

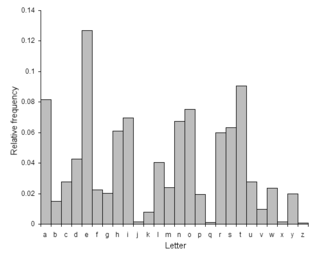

Another brute force approach is to match up the frequency distribution of the letters. By graphing the frequencies of letters in the ciphertext, and by knowing the expected distribution of those letters in the original language of the plaintext, a human can easily spot the value of the shift by looking at the displacement of particular features of the graph. This is known as frequency analysis. For example in the English language the plaintext frequencies of the letters E, T, (usually most frequent), and Q, Z (typically least frequent) are particularly distinctive.[16] Computers can also do this by measuring how well the actual frequency distribution matches up with the expected distribution; for example, the chi-square statistic can be used.[17]

For natural language plaintext, there will, in all likelihood, be only one plausible decryption, although for extremely short plaintexts, multiple candidates are possible. For example, the ciphertext MPQY could, plausibly, decrypt to either "aden" or "know" (assuming the plaintext is in English); similarly, "ALIIP" to "dolls" or "wheel"; and "AFCCP" to "jolly" or "cheer" (see also unicity distance).

Multiple encryptions and decryptions provide no additional security. This is because two encryptions of, say, shift A and shift B, will be equivalent to an encryption with shift A + B. In mathematical terms, the encryption under various keys forms a group.[18]

[edit] Notes

- ^ Luciano, Dennis; Gordon Prichett (January 1987). "Cryptology: From Caesar Ciphers to Public-Key Cryptosystems". The College Mathematics Journal 18 (1): 3. doi:.

- ^ Wobst, Reinhard (2001). Cryptology Unlocked. Wiley. pp. 19. ISBN 978-0470060643.

- ^ Reinke, Edgar C. (December 1992). "Classical Cryptography". The Classical Journal 58 (3): 114.

- ^ Pieprzyk, Josef; Thomas Hardjono, Jennifer Seberry (2003). Fundamentals of Computer Security. Springer. pp. 6. ISBN 3540431012.

- ^ Singh, Simon (2000). The Code Book. Anchor. pp. 14–20. ISBN 0385495323.

- ^ Alexander Poltorak. "Mezuzah and Astrology". chabad.org. http://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/312102/jewish/Mezuzah-and-Astrology.htm. Retrieved on 2008-06-13.

- ^ Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers. pp. 775–6. ISBN 978-0-684-83130-5).

- ^ Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers. pp. 631–2. ISBN 978-0-684-83130-5).

- ^ Wobst, Reinhard (2001). Cryptology Unlocked. Wiley. pp. 20. ISBN 978-0470060643.

- ^ Kahn, David (1967). The Codebreakers. ISBN 978-0-684-83130-5).

- ^ Leyden, John (2006-04-19). "Mafia boss undone by clumsy crypto". The Register. http://www.theregister.co.uk/2006/04/19/mafia_don_clueless_crypto/. Retrieved on 2008-06-13.

- ^ Beutelspacher, Albrecht (1994). Cryptology. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 9–11. ISBN 0-88385-504-6.

- ^ Beutelspacher, Albrecht (1994). Cryptology. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-88385-504-6.

- ^ Leighton, Albert C. (April 1969). "Secret Communication among the Greeks and Romans". Technology and Culture 10 (2): 153. doi:.

- ^ Sinkov, Abraham; Paul L. Irwin (1966). Elementary Cryptanalysis: A Mathematical Approach. Mathematical Association of America. pp. 13–15. ISBN 0883856220.

- ^ Singh, Simon (2000). The Code Book. Anchor. pp. 72–77. ISBN 0385495323.

- ^ Savarese, Chris; Brian Hart (2002-07-15). "The Caesar Cipher". http://starbase.trincoll.edu/~crypto/historical/caesar.html. Retrieved on 2008-07-16.

- ^ Wobst, Reinhard (2001). Cryptology Unlocked. Wiley. pp. 31. ISBN 978-0470060643.

[edit] Bibliography

- David Kahn, The Codebreakers — The Story of Secret Writing, 1967. ISBN 0-684-83130-9.

- F.L. Bauer, Decrypted Secrets, 2nd edition, 2000, Springer. ISBN 3-540-66871-3.

- Chris Savarese and Brian Hart, The Caesar Cipher, 1999

[edit] External links

- The Caesar Shift discussed on The Beginner's Guide to Cryptography

- Caesar shift decoder showing all 25 possible codes for any given cipher

- Java implementation of Caesar cipher

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||