Television

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2008) |

Television (TV) is a widely used telecommunication medium for transmitting and receiving moving images, either monochromatic ("black and white") or color, usually accompanied by sound. "Television" may also refer specifically to a television set, television programming or television transmission. The word is derived from mixed Latin and Greek roots, meaning "far sight": Greek tele (τῆλε), far, and Latin visio, sight (from video, vis- to see, or to view in the first person).

Commercially available since the late 1930s, the television set has become a common communications receiver in homes, businesses and institutions, particularly as a source of entertainment and news. Since the 1970s the availability of video cassettes, laserdiscs, DVDs and now Blu-ray discs, have resulted in the television set frequently being used for viewing recorded as well as broadcast material.

A standard television set comprises multiple internal electronic circuits, including those for tuning and decoding broadcast signals. A display device which lacks a tuner is properly called a monitor, rather than a television. A television system may use different technical standards such as digital television (DTV) and high-definition television (HDTV). Television systems are also used for surveillance, industrial process control, and guiding of weapons, in places where direct observation is difficult or dangerous.

Amateur television (HAM TV or ATV) is also used for experimentation, pleasure and public service events by amateur radio operators. HAM TV stations were on the air in many cities before commercial TV stations came on the air - see http://www.earlytelevision.org/1940_home_camera.html for more info.

Contents |

History

In its early stages of development, television included only those devices employing a combination of optical, mechanical and electronic technologies to capture, transmit and display a visual image. By the late 1920s, however, those employing only optical and electronic technologies were being explored. All modern television systems rely on the latter, however the knowledge gained from the work on mechanical-dependent systems was crucial in the development of fully electronic television.

The first time images were transmitted electrically were via early mechanical fax machines, including the pantelegraph. The concept of electrically-powered transmission of television images in motion, was first sketched in 1878 as the telephonoscope, shortly after the invention of the telephone. At the time, it was imagined by early science fiction authors, that someday that light could be transmitted over wires, as sounds were.[citation needed]

The idea of using scanning to transmit images was put to actual practical use in 1881 in the pantelegraph, through the use of a pendulum-based scanning mechanism. From this period forward, scanning in one form or another, has been used in nearly every image transmission technology to date, including television. This is the concept of "rasterization", the process of converting a visual image into a stream of electrical pulses.[citation needed]

In 1884 Paul Gottlieb Nipkow, a 20-year old university student in Germany, patented the first electromechanical television system which employed a scanning disk, a spinning disk with a series of holes spiraling toward the center, for rasterization. The holes were spaced at equal angular intervals such that in a single rotation the disk would allow light to pass through each hole and onto a light-sensitive selenium sensor which produced the electrical pulses. As an image was focused on the rotating disk, each hole captured a horizontal "slice" of the whole image, in a scanning fashion.[citation needed]

Nipkow's design would not be practical until advances in amplifier tube technology became available in 1907. Even then the device was only useful for transmitting still "halftone" images - represented by equally spaced dots of varying size - over telegraph or telephone lines. Later designs would use a rotating mirror-drum scanner to capture the image and a cathode ray tube (CRT) as a display device, but moving images were still not possible, due to the poor sensitivity of the selenium sensors.[citation needed]

Scottish inventor John Logie Baird demonstrated the transmission of moving silhouette images in London in 1925, and of moving, monochromatic images in 1926. Baird's scanning disk produced an image of 30 lines resolution, barely enough to discern a human face, from a double spiral of lenses.[citation needed]

In 1926, Hungarian engineer Kálmán Tihanyi invented the entirely electronic camera tube and entirely electronic display and the transmitting and receiving system.[1][2][3] [4]

By 1927, Russian inventor Léon Theremin developed a mirror drum-based television system which used interlacing to achieve an image resolution of 100 lines.[citation needed]

Also in 1927, Herbert E. Ives of Bell Labs transmitted moving images from a 50-aperture disk producing 16 frames per minute over a cable from Washington, DC to New York City, and via radio from Whippany, New Jersey. Ives used viewing screens as large as 24 by 30 inches (60 by 75 centimeters). His subjects included Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover.[citation needed]

In 1928, Philo Farnsworth made the world's first working television system with electronic scanning of both the pickup and display devices, which he first demonstrated to news media on 1 September 1928, televising a motion picture film.[citation needed]

In 1936, Kálmán Tihanyi described the principle of Plasma Television, the first flat panel. [5] [6]

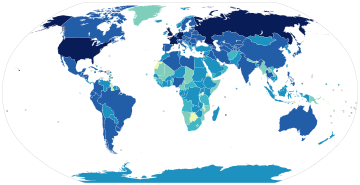

Geographical usage

Content

Programming

Getting TV programming shown to the public can happen in many different ways. After production the next step is to market and deliver the product to whatever markets are open to using it. This typically happens on two levels:

- Original Run or First Run – a producer creates a program of one or multiple episodes and shows it on a station or network which has either paid for the production itself or to which a license has been granted by the producers to do the same.

- Syndication – this is the terminology rather broadly used to describe secondary programming usages (beyond original run). It includes secondary runs in the country of first issue, but also international usage which may or may not be managed by the originating producer. In many cases other companies, TV stations or individuals are engaged to do the syndication work, in other words to sell the product into the markets they are allowed to sell into by contract from the copyright holders, in most cases the producers.

First run programming is increasing on subscription services outside the U.S., but few domestically produced programs are syndicated on domestic FTA elsewhere. This practice is increasing however, generally on digital-only FTA channels, or with subscriber-only first run material appearing on FTA.

Unlike the U.S., repeat FTA screenings of a FTA network program almost only occur on that network. Also, Affiliates rarely buy or produce non-network programming that is not centred around local events.

Funding

| The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article or discuss the issue on the talk page. |

Around the globe, broadcast television is financed by either government, advertising, licensing (a form of tax), subscription or any combination of these. To protect revenues, subscription TV channels are usually encrypted to ensure that only subscription payers receive the decryption codes to see the signal. Non-encrypted channels are known as Free to Air or FTA.

Advertising

Television's broad reach makes it a powerful and attractive medium for advertisers. Many television networks and stations sell blocks of broadcast time to advertisers ("sponsors") in order to fund their programming.

United States

Since inception in the U.S. in 1940, TV commercials have become one of the most effective, persuasive, and popular method of selling products of many sorts, especially consumer goods. U.S. advertising rates are determined primarily by Nielsen Ratings. The time of the day and popularity of the channel determine how much a television commercial can cost. For example, the highly popular American Idol can cost approximately $750,000 for a thirty second block of commercial time; while the same amount of time for the World Cup and the Super Bowl can cost several million dollars.

In recent years, the paid program or infomercial has become common, usually in lengths of 30 minutes or one hour. Some drug companies and other businesses have even created "news" items for broadcast, known in the industry as video news releases, paying program directors to use them.[7]

Some TV programs also weave advertisements into their shows, a practice begun in film and known as product placement. For example, a character could be drinking a certain kind of soda, going to a particular chain restaurant, or driving a certain make of car. (This is sometimes very subtle, where shows have vehicles provided by manufacturers for low cost, rather than wrangling them.) Sometimes a specific brand or trade mark, or music from a certain artist or group, is used. (This excludes guest appearances by artists, who perform on the show.)

United Kingdom

The TV regulator oversees TV advertising in the United Kingdom. Its restrictions have applied since the early days of commercially funded TV. Despite this, an early TV mogul, Lew Grade, likened the broadcasting licence as a being a "licence to print money". Restrictions mean that the big three national commercial TV channels: ITV, Channel 4, and Five can show an average of only seven minutes of advertising per hour (eight minutes in the peak period). Other broadcasters must average no more than nine minutes (twelve in the peak). This means that many imported TV shows from the US have unnatural breaks where the UK company has edited out the breaks intended for US advertising. Advertisements must not be inserted in the course of certain specific proscribed types of programs which last less than half an hour in scheduled duration, this list includes any news or current affairs program, documentaries, and programs for children. Nor may advertisements be carried in a program designed and broadcast for reception in schools or in any religious service or other devotional program, or during a formal Royal ceremony or occasion. There also must be clear demarcations in time between the programs and the advertisements.

The BBC, being strictly non-commercial is not allowed to show advertisements on television in the UK, although it has many advertising-funded channels abroad. The majority of its budget comes from TV licencing (see below) and the sale of content to other broadcasters.

Taxation or TV License

Television services in some countries may be funded by a television licence, a form of taxation which means advertising plays a lesser role or no role at all. For example, some channels may carry no advertising at all and some very little.

The BBC carries no advertising on its UK channels and is funded by an annual licence paid by all households owning a television. This licence fee is set by government, but the BBC is not answerable to or controlled by government and is therefore genuinely independent.

The two main BBC TV channels are watched by almost 90 percent of the population each week and overall have 27 per cent share of total viewing.[8] This in spite of the fact that 85% of homes are multichannel, with 42% of these having access to 200 free to air channels via satellite and another 43% having access to 30 or more channels via Freeview.[9] The licence that funds the seven advertising-free BBC TV channels currently costs £139.50 a year (about US$215) irrespective of the number of TV sets owned. When the same sporting event has been presented on both BBC and commercial channels, the BBC always attracts the lion's share of the audience, indicating viewers prefer to watch TV uninterrupted by advertising.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) carries no advertising (except for the ABC shop) as it is banned under law ABC Act 1983. The ABC receives its funding from the Australian Government every three years. In the 2006/07 Federal Budget the ABC received Au$822.67 Million[10] this covers most of the ABC funding commitments and as with the BBC also funds radio channels, transmitters and the ABC web sites. The ABC also receives funds from its many ABC Shops in Australia.

In France government-funded channels do carry advertisements yet those who own television sets have to pay an annual tax ("la redevance audiovisuelle").

Subscription

Some TV channels are partly funded from subscriptions and therefore the signals are encrypted during broadcast to ensure that only paying subscribers have access to the decryption codes. Most subscription services are also funded by advertising.

Television genres

Television genres include a broad range of programming types that entertain, inform, and educate viewers. The most expensive entertainment genres to produce are usually drama and dramatic miniseries. However, other genres, such as historical Western genres, may also have high production costs.

Popular entertainment genres include action-oriented shows such as police, crime, detective dramas, horror, or thriller shows. As well, there are also other variants of the drama genre, such as medical dramas and daytime soap operas. Science fiction shows can fall into either the drama or action category, depending on whether they emphasize philosophical questions or high adventure. Comedy is a popular genre which includes situation comedy (sitcom) and animated shows for the adult demographic such as Family Guy.

The least expensive forms of entertainment programming are game shows, talk shows, variety shows, and reality TV. Game shows show contestants answering questions and solving puzzles to win prizes. Talk shows feature interviews with film, television and music celebrities and public figures. Variety shows feature a range of musical performers and other entertainers such as comedians and magicians introduced by a host or Master of Ceremonies. There is some crossover between some talk shows and variety shows, because leading talk shows often feature performances by bands, singers, comedians, and other performers in between the interview segments. Reality TV shows "regular" people (i.e., not actors) who are facing unusual challenges or experiences, ranging from arrest by police officers (COPS) to weight loss (The Biggest Loser). A variant version of reality shows depicts celebrities doing mundane activities such as going about their everyday life (Snoop Dogg's Father Hood) or doing manual labour (Simple Life).

Social aspects

Television has played a pivotal role in the socialization of the 20th and 21st centuries. There are many social aspects of television that can be addressed, including:

Environmental aspects

With high lead content in CRTs, and the rapid diffusion of new, flat-panel display technologies, some of which (LCDs) use lamps containing mercury, there is growing concern about electronic waste from discarded televisions. Related occupational health concerns exist, as well, for disassemblers removing copper wiring and other materials from CRTs. Further environmental concerns related to television design and use relate to the devices' increasing electrical energy requirements.[11]

In numismatics

Television has had such an impact in today's life, that it has been the main motif for numerous collectors' coins and medals. One of the most recent ones is the Austrian 50 years of Television commemorative coin minted in March 9, 2005. The obverse of the coin shows a "test pattern", while the reverse shows several milestones in the history of television.

References

- ^ "Hungary - Kálmán Tihanyi's 1926 Patent Application 'Radioskop'". Memory of the World. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=23240&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Retrieved on 2008-02-22.

- ^ United States Patent Office, Patent No. 2,133,123, Oct. 11, 1938.

- ^ United States Patent Office, Patent No. 2,158,259, May 16, 1939

- ^ http://www.bairdtelevision.com/zworykin.html

- ^ http://www.scitech.mtesz.hu/52tihanyi/flat-panel_tv_en.pdf

- ^ http://www.gadgetrepublic.com/news/item/202/

- ^ Jon Stewart of "The Daily Show" was mock-outraged at this, saying, "That's what we do!", and calling it a new form of television, "infoganda".

- ^ http://www.barb.co.uk/viewingsummary/weekreports.cfm?report=multichannel&requesttimeout=500&flag=viewingsummary viewing statistics in UK

- ^ http://www.ofcom.org.uk/research/tv/reports/dtv/dtv_2007_q3/dtvq307.pdf OFCOM quarterly survey

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/corp/pubs/documents/budget2006-07.pdf

- ^ "The Rise of the Machines: A Review of Energy Using Products in the Home from the 1970s to Today" (PDF). Energy Saving Trust. July 3, 2006. http://www.energysavingtrust.org.uk/uploads/documents/aboutest/Riseofthemachines.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-08-31.

See also

- Broadcast safe

- History of television

- How television works

- Internet television

- Technology of television

- List of countries by number of television broadcast stations

- List of television manufacturers

- List of years in television

- Media psychology

Further reading

![]() Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks

![]() Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote

![]() Source texts from Wikisource

Source texts from Wikisource

![]() Images and media from Commons

Images and media from Commons

![]() News stories from Wikinews

News stories from Wikinews

- Albert Abramson, The History of Television, 1942 to 2000, Jefferson, NC, and London, McFarland, 2003, ISBN 0786412208.

- Pierre Bourdieu, On Television, The New Press, 2001.

- Tim Brooks and Earle March, The Complete Guide to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 8th ed., Ballantine, 2002.

- Jacques Derrida and Bernard Stiegler, Echographies of Television, Polity Press, 2002.

- David E. Fisher and Marshall J. Fisher, Tube: the Invention of Television, Counterpoint, Washington, DC, 1996, ISBN 1887178171.

- Steven Johnson, Everything Bad is Good for You: How Today's Popular Culture Is Actually Making Us Smarter, New York, Riverhead (Penguin), 2005, 2006, ISBN 1594481946.

- Jerry Mander, Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, Perennial, 1978.

- Jerry Mander, In the Absence of the Sacred, Sierra Club Books, 1992, ISBN 0871565099.

- Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, New York, Penguin US, 1985, ISBN 0670804541.

- Evan I. Schwartz, The Last Lone Inventor: A Tale of Genius, Deceit, and the Birth of Television, New York, Harper Paperbacks, 2003, ISBN 0060935596.

- Beretta E. Smith-Shomade, Shaded Lives: African-American Women and Television, Rutgers University Press, 2002.

- Alan Taylor, We, the Media: Pedagogic Intrusions into US Mainstream Film and Television News Broadcasting Rhetoric, Peter Lang, 2005, ISBN 3631518528.

External links

- The Encyclopedia of Television at the Museum of Broadcast Communications

- The Evolution of TV, A Brief History of TV Technology in Japan NHK

- Television's History — The First 75 Years

- Worldwide Television Standards

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||