Giant impact hypothesis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The giant impact hypothesis (sometimes referred to as the big whack, or, less frequently, the big splash) is the now-dominant[citation needed] scientific hypothesis for the formation of the Moon, which is thought to have formed as a result of a collision between the young Earth and a Mars-sized body that is sometimes called Theia.[1] Evidence for this hypothesis includes moon samples which indicate the surface of the moon was once molten, the moon's apparently relatively small iron core, and evidence of similar collisions in other star systems. Questions remaining to be resolved about this hypothesis include why lunar samples do not have ratios of volatile elements, iron oxide, or siderophilic elements which would be implied by this hypothesis, as well as what evidence may suggest the earth ever had the magma ocean implied by this hypothesis.

Contents |

[edit] Origins

The hypothesis was first proposed by Reginald Aldworth Daly of Harvard University in the 1940s as a challenge to or an adjustment of the previously dominant theory postulated by George Howard Darwin. Darwin's theory was that a molten moon was spun out of a parent planet, based on his belief that Newtonian mechanics showed the Moon had actually orbited much closer to the earth and was moving away from the earth. This was proved later by NASA and Soviet tests. Darwin's calculations could not be resolved, however, in a way that carried the moon back to the surface of the earth. Professor Daly's theory laid dormant until it was reintroduced at a conference on satellites in 1974 and then republished in Icarus in 1975 by Drs. William K. Hartmann and Donald R. Davis.[citation needed]

[edit] Theia

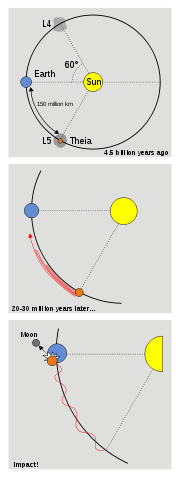

The name Theia is derived from the Greek goddess Theia, a Titan who gave birth to the Moon goddess Selene. According to the giant impact hypothesis, Theia formed along with the other planets of our solar system about 4.5 billion years ago, and was approximately the size of Mars. It would have materialized at the L4 or L5 Lagrangian points relative to Earth (in about the same orbit and about 60° ahead or behind),[2] similar to a trojan asteroid.[3]

However, the stability of Theia's orbit was affected when its growing mass exceeded a threshold. At some point, greater gravitational interaction with the proto-Earth locked the bodies into an ultimate collision course.

[edit] Impact

In astronomical terms, the impact would have been of moderate velocity. Theia is thought to have struck the Earth at an oblique angle. Theia's iron core sank into the young Earth's core, as most of Theia's mantle and a significant portion of the Earth's mantle and crust were ejected into orbit around the Earth. This material quickly coalesced into the Moon (possibly within less than a month, but in no more than a century). Estimates based on computer simulations of such an event suggest that some two percent of the original mass of Theia ended up as an orbiting ring of debris, and about half of this matter coalesced into the Moon. The Earth would have gained significant amounts of angular momentum and mass from such a collision. Regardless of the rotation and inclination the Earth had before the impact, it would have had a day some five hours long after the impact, and the Earth's equator would have shifted closer to the plane of the Moon's orbit.[citation needed]

It has been suggested that other significant objects may have been created by the impact, which could have remained in orbit between the Earth and Moon, stuck in Lagrangian points. Such objects may have stayed within the Earth-Moon system for up to 100 million years, until the gravitational tugs of other planets destabilized the system enough to free the objects.[4]

[edit] Evidence

Indirect evidence for this impact scenario comes from rocks collected during the Apollo Moon landings, which show oxygen isotope compositions that are nearly the same as the Earth. The highly anorthositic composition of the lunar crust, as well as the existence of KREEP-rich samples, gave rise to the idea that a large portion of the Moon was once molten, and a giant impact scenario could easily have supplied the energy needed to form such a magma ocean. Several lines of evidence show that if the Moon has an iron-rich core, it must be small. In particular, the mean density, moment of inertia, rotational signature, and magnetic induction response all suggest that the radius of the core is less than about 25% the radius of the Moon, in contrast to about 50% for most of the other terrestrial bodies. Impact conditions can be found that give rise to a Moon that formed mostly from the mantles of the Earth and impactor, with the core of the impactor accreting to the Earth, and which satisfy the angular momentum constraints of the Earth-Moon system.[5]

A belt of warm dust in a zone between 0.25AU and 2AU from the young star HD 23514 in the Pleiades cluster appears similar to the predicted results of Theia's collision with the embryonic Earth, and has been interpreted as the result of planet-sized objects colliding with each other.[6] This is similar to another belt of warm dust detected around the star BD+20 307 (HIP 8920, SAO 75016).[7]

[edit] Difficulties

This lunar origin hypothesis has some difficulties which have yet to be explained. These difficulties include:

- Ratios of the Moon's volatile elements are not consistent with the giant impact hypothesis (not resolved as of 1998[update])[8]

- There is no evidence that the Earth ever had a magma ocean (an implied result of the giant impact hypothesis), and it is likely there exists material which has never been processed by a magma ocean (not resolved as of 1998[update])[8]

- Iron oxide (FeO) content of 13% of the bulk Moon properties rule out the derivation of the proto-lunar material from any but a small fraction of Earth's mantle (not resolved as of 1997[update])[9]

- If the bulk of the proto-lunar material had come from the impactor, the Moon should be enriched in siderophilic elements, when it is actually deficient of those (not resolved as of 2005[update])[10]

[edit] Alternate hypotheses

Other mechanisms which have been suggested at various times for the Moon's origin are that the Moon was spun off of the Earth's surface by centrifugal force,[11] that it was formed elsewhere and later captured by the Earth's gravitational field,[12] and that the Moon formed at the same time and place as the Earth from the same accretion disk. Each of these mechanisms is claimed to lack a mechanism to account for the high angular momentum of the Earth–Moon system.[13]

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ U. Wiechert, A. N. Halliday, D.-C. Lee, G. A. Snyder, L. A. Taylor, D. Rumble (October 2001). Science. 294. pp. 345–348.[1]

- ^ Belbruno, E.; J. Richard Gott III (2005). "Where Did The Moon Come From?". The Astronomical Journal 129 (3): 1724–1745. doi:. arΧiv:astro-ph/0405372.

- ^ Mackenzie, Dana (2003). The Big Splat, or How The Moon Came To Be. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471150572.

- ^ Ker Than (6 May 2008). "Did Earth once have multiple moons?". New Scientist. http://space.newscientist.com/article/dn13836-did-earth-once-have-multiple-moons.html?feedId=online-news_rss20.

- ^ R. Canup and E. Asphaug (2001). "Origin of the Moon in a giant impact near the end of the Earth's formation". Nature 412: 708–712. doi:.

- ^ Rhee, Joseph H.; Inseok Song, B. Zuckerman (2007). "Warm dust in the terrestrial planet zone of a sun-like Pleiad: collisions between planetary embryos?". ApJ. arΧiv:0711.2111v1.

- ^ Song, Inseok; B. Zuckerman, Alycia J. Weinberger and E. E. Becklin (21 July 2005). "Extreme collisions between planetesimals as the origin of warm dust around a Sun-like star". Nature 436: 363–365. doi:.

- ^ a b Tests of the Giant Impact Hypothesis, J. H. Jones, Lunar and Planetary Science, Origin of the Earth and Moon Conference, 1998 [2].

- ^ The Bulk Composition of the Moon, Stuart R. Taylor, Lunar and Planetary Science, 1997, [3]

- ^ E. M. Galimov and A. M. Krivtsov (December 2005). "Origin of the Earth-Moon System". J. Earth Syst. Sci. 114 (6): 593–600. doi:. [4]

- ^ Binder, A.B. (1974). "On the origin of the moon by rotational fission". The Moon 11 (2): 53–76. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1974Moon...11...53B. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

- ^ Mitler, H.E. (1975). "Formation of an iron-poor moon by partial capture, or: Yet another exotic theory of lunar origin". Icarus 24: 256–268. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1975Icar...24..256M. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

- ^ Stevenson, D.J. (1987). "Origin of the moon–The collision hypothesis". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 15: 271–315. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1987AREPS..15..271S. Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

[edit] Further reading

- Academic articles

- William K. Hartmann and Donald R. Davis, Satellite-sized planetesimals and lunar origin, (International Astronomical Union, Colloquium on Planetary Satellites, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., Aug. 18-21, 1974) Icarus, vol. 24, April 1975, p. 504-515

- Alastair G. W. Cameron and William R. Ward, The Origin of the Moon, Abstracts of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, volume 7, page 120, 1976

- Canup, R. M.; Asphaug, E. (Fall Meeting 2001). "An impact origin of the Earth-Moon system". Abstract #U51A-02, American Geophysical Union. Retrieved on 2007-03-10.

- R. Canup and K. Righter, editors (2000). Origin of the Earth and Moon. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. pp. 555 pp.

- Charles Shearer and 15 coauthors (2006). "Thermal and magmatic evolution of the Moon". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 60: 365–518. doi:.

- Non-academic books

- Dana Mackenzie, The Big Splat, or How Our Moon Came to Be, 2003, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-15057-6.

- G. Jeffrey Taylor (December 31, 1998). "Origin of the Earth and Moon". Planetary Science Research Discoveries. http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/Dec98/OriginEarthMoon.html.

[edit] External links

- Planetary Science Institute: Giant Impact Hypothesis

- Computer modelling of the Moon's creation (Space.com)

- Origin of the Moon by Prof. AGW Cameron

- Klemperer Rosette simulations using Java applets

- SwRI giant impact hypothesis simulation (.wmv and .mov)

- Origin of the Moon - computer model of accretion

- Moon Archive - Including articles about the giant impact hypothesis

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||