Net present value

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Net present value (NPV) or net present worth (NPW)[1] is defined as the total present value (PV) of a time series of cash flows. It is a standard method for using the time value of money to appraise long-term projects. Used for capital budgeting, and widely throughout economics, it measures the excess or shortfall of cash flows, in present value terms, once financing charges are met.

See discounted cash flow.

Contents |

[edit] Formula

Each cash inflow/outflow is discounted back to its present value (PV). Then they are summed. Therefore NPV is the sum of all terms  , where

, where

- t - the time of the cash flow

- i - the discount rate (the rate of return that could be earned on an investment in the financial markets with similar risk.)

- Rt - the net cash flow (the amount of cash, inflow minus outflow) at time t (for educational purposes, R0 is commonly placed to the left of the sum to emphasize its role as (minus the) investment).

[edit] The discount rate

The rate used to discount future cash flows to their present values is a key variable of this process. A firm's weighted average cost of capital (after tax) is often used, but many people believe that it is appropriate to use higher discount rates to adjust for risk for riskier projects or other factors. A variable discount rate with higher rates applied to cash flows occurring further along the time span might be used to reflect the yield curve premium for long-term debt.

Another approach to choosing the discount rate factor is to decide the rate which the capital needed for the project could return if invested in an alternative venture. If, for example, the capital required for Project A can earn five percent elsewhere, use this discount rate in the NPV calculation to allow a direct comparison to be made between Project A and the alternative. Related to this concept is to use the firm's Reinvestment Rate. Reinvestment rate can be defined as the rate of return for the firm's investments on average. When analyzing projects in a capital constrained environment, it may be appropriate to use the reinvestment rate rather than the firm's weighted average cost of capital as the discount factor. It reflects opportunity cost of investment, rather than the possibly lower cost of capital.

A NPV amount obtained using variable discount rates (if they are known for the duration of the investment) better reflects the real situation than that calculated from a constant discount rate for the entire investment duration. Refer to the tutorial article written by Samuel Baker[2] for more detailed relationship between the NPV value and the discount rate.

For some professional investors, their investment funds are committed to target a specified rate of return. In such cases, that rate of return should be selected as the discount rate for the NPV calculation. In this way, a direct comparison can be made between the profitability of the project and the desired rate of return.

To some extent, the selection of the discount rate is dependent on the use to which it will be put. If the intent is simply to determine whether a project will add value to the company, using the firm's weighted average cost of capital may be appropriate. If trying to decide between alternative investments in order to maximize the value of the firm, the corporate reinvestment rate would probably be a better choice.

Using variable rates over time, or discounting "guaranteed" cash flows different from "at risk" cash flows may be a superior methodology, but is seldom used in practice. Using the discount rate to adjust for risk is often difficult to do in practice (especially internationally), and is really difficult to do well. An alternative to using discount factor to adjust for risk is to explicitly correct the cash flows for the risk elements using rNPV or a similar method, then discount at the firm's rate.

[edit] What NPV Means

NPV is an indicator of how much value an investment or project adds to the firm. With a particular project, if Ct is a positive value, the project is in the status of discounted cash inflow in the time of t. If Ct is a negative value, the project is in the status of discounted cash outflow in the time of t. Appropriately risked projects with a positive NPV could be accepted. This does not necessarily mean that they should be undertaken since NPV at the cost of capital may not account for opportunity cost, i.e. comparison with other available investments. In financial theory, if there is a choice between two mutually exclusive alternatives, the one yielding the higher NPV should be selected. The following sums up the NPVs in various situations.

| If... | It means... | Then... |

|---|---|---|

| NPV > 0 | the investment would add value to the firm | the project may be accepted |

| NPV < 0 | the investment would subtract value from the firm | the project should be rejected |

| NPV = 0 | the investment would neither gain nor lose value for the firm | We should be indifferent in the decision whether to accept or reject the project. This project adds no monetary value. Decision should be based on other criteria, e.g. strategic positioning or other factors not explicitly included in the calculation. |

However, NPV = 0 does not mean that a project is only expected to break even, in the sense of undiscounted profit or loss (earnings). It will show net total positive cash flow and earnings over its life.

[edit] Example

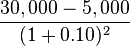

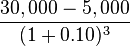

A corporation must decide whether to introduce a new product line. The new product will have startup costs, operational costs, and incoming cash flows over six years. This project will have an immediate (t=0) cash outflow of $100,000 (which might include machinery, and employee training costs). Other cash outflows for years 1-6 are expected to be $5,000 per year. Cash inflows are expected to be $30,000 each for years 1-6. All cash flows are after-tax, and there are no cash flows expected after year 6. The required rate of return is 10%. The present value (PV) can be calculated for each year:

| Year | Cashflow | Present Value |

|---|---|---|

| T=0 |  |

-$100,000 |

| T=1 |  |

$22,727 |

| T=2 |  |

$20,661 |

| T=3 |  |

$18,783 |

| T=4 |  |

$17,075 |

| T=5 |  |

$15,523 |

| T=6 |  |

$14,112 |

The sum of all these present values is the net present value, which equals $8,881.52. Since the NPV is greater than zero, it would be better to invest in the project than to do nothing, and the corporation should invest in this project if there is no alternative with a higher NPV.

The same example in Excel formulae:

- NPV(rate,net_inflow)+initial_investment

- PV(rate,year_number,yearly_net_inflow)

More realistic problems would need to consider other factors, generally including the calculation of taxes, uneven cash flows, and salvage values as well as the availability of alternate investment opportunities.

[edit] Common pitfalls

- If for example the Ct are generally negative late in the project (e.g., an industrial or mining project might have clean-up and restoration costs), then at that stage the company owes money, so a high discount rate is not cautious but too optimistic. Some people see this as a problem with NPV. A way to avoid this problem is to include explicit provision for financing any losses after the initial investment, that is, explicitly calculate the cost of financing such losses.

- Another common pitfall is to adjust for risk by adding a premium to the discount rate. Whilst a bank might charge a higher rate of interest for a risky project, that does not mean that this is a valid approach to adjusting a net present value for risk, although it can be a reasonable approximation in some specific cases. One reason such an approach may not work well can be seen from the foregoing: if some risk is incurred resulting in some losses, then a discount rate in the NPV will reduce the impact of such losses below their true financial cost. A rigorous approach to risk requires identifying and valuing risks explicitly, e.g. by actuarial or Monte Carlo techniques, and explicitly calculating the cost of financing any losses incurred.

- Yet another issue can result from the compounding of the risk premium. R is a composite of the risk free rate and the risk premium. As a result, future cash flows are discounted by both the risk-free rate as well as the risk premium and this effect is compounded by each subsequent cash flow. This compounding results in a much lower NPV than might be otherwise calculated. The certainty equivalent model can be used to account for the risk premium without compounding its effect on present value.[citation needed]

- If NPV is less than 0, which is to say, negative, the project should not be immediately rejected. Sometimes companies have to execute an NPV-negative project if not executing it creates even more value destruction.

- Another issue with relying on NPV is that it does not provide an overall picture of the gain or loss of executing a certain project. To see a percentage gain relative to the investments for the project, usually, Internal Rate of Return is used complimented to the NPV method.

[edit] Alternative capital budgeting methods

- Payback period: which measures the time required for the cash inflows to equal the original outlay. It measures risk, not return.

- Cost-benefit analysis: which includes issues other than cash, such as time savings.

- Real option method: which attempts to value managerial flexibility that is assumed away in NPV.

- Internal rate of return: which calculates the rate of return of a project without making assumptions about the reinvestment of the cash flows (hence internal).

- Modified internal rate of return (MIRR): similar to IRR, but it makes explicit assumptions about the reinvestment of the cash flows. Sometimes it is called Growth Rate of Return.

- Accounting rate of return.

[edit] References

- ^ Lin, Grier C. I.; Nagalingam, Sev V. (2000). CIM justification and optimisation. London: Taylor & Francis. pp. 36. ISBN 0-7484-0858-4.

- ^ Baker, Samuel L. (2000). "Perils of the Internal Rate of Return". http://hspm.sph.sc.edu/COURSES/ECON/invest/invest.html. Retrieved on January 12.

[edit] External links

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||