Bayesian probability

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bayesian probability interprets the concept of probability as 'a measure of a state of knowledge' [1], and not as a frequency as in orthodox statistics. Broadly speaking, there are two views on Bayesian probability that interpret the 'state of knowledge' concept in different ways. For the objectivist school, the rules of Bayesian statistics can be justified by desiderata of rationality and consistency and interpreted as an extension of Aristotelian logic[2][1]. For the subjectivist school, the state of knowledge corresponds to a 'personal belief' [3]. Many modern machine learning methods are based on objectivist Bayesian principles [4]. One of the crucial features of the Bayesian view is that a probability can be assigned to a hypothesis, which is not possible under the frequentist view, where a hypothesis can only be rejected or not rejected.

Contents |

[edit] The Bayesian probability calculus

According to the Bayesian probability calculus, the probability of a hypothesis given the data (the posterior) is proportional to the product of the likelihood times the prior probability (often just called the prior). The likelihood brings in the effect of the data, while the prior specifies the belief in the hypothesis before the data was observed.

More formally, the Bayesian probability calculus makes use of Bayes' formula - a theorem that is valid in all common interpretations of probability - in the following way:

where

- H is a hypothesis, and D is the data.

- P(H) is the prior probability of H: the probability that H is correct before the data D was seen.

- P(D | H) is the conditional probability of seeing the data D given that the hypothesis H is true. P(D | H) is called the likelihood.

- P(D) is the marginal probability of D.

- P(H | D) is the posterior probability: the probability that the hypothesis is true, given the data and the previous state of belief about the hypothesis.

P(D) is the a priori probability of witnessing the data D under all possible hypotheses. Given any exhaustive set of mutually exclusive hypotheses Hi, we have:

.

.

We can consider i here to index alternative worlds, of which there is exactly one which we inhabit, and Hi is the hypothesis that we are in the world i. P(D,Hi) is then the probability that we are in the world i and witness the data. Since the set of alternative worlds was assumed to be mutually exclusive and exhaustive, the above formula is a case of the law of alternatives.

P(D) is a normalizing constant that only depends on the data, and which in most cases does not need to be computed explicitly. As a result, Bayes' formula is often simplified to:

where  denotes proportionality.

denotes proportionality.

In general, Bayesian methods are characterized by the following concepts and procedures:

- The use of hierarchical models, and the marginalization over the values of nuisance parameters. In most cases, the computation is intractable, but good approximations can be obtained using Markov chain Monte Carlo methods.

- The sequential use of the Bayes' formula: when more data becomes available after calculating a posterior distribution, the posterior becomes the next prior.

- In frequentist statistics, a hypothesis can only be rejected or not rejected. In Bayesian statistics, a probability can be assigned to a hypothesis.

The objective and subjective variants of Bayesian probability differ mainly in their interpretation and construction of the prior probability.

[edit] History

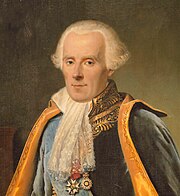

The term Bayesian refers to Thomas Bayes (1702–1761), who proved a special case of what is now called Bayes' theorem. However, it was Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827) who introduced a general version of the theorem and used it to approach problems in celestial mechanics, medical statistics, reliability, and jurisprudence [5].

The frequentist view of probability overshadowed the Bayesian view during the first half of the 20th century due to prominent figures such as Ronald Fisher, Jerzy Neyman and Egon Pearson. The word Bayesian appeared in the 1950s, and by the 1960s it became the term preferred by people who sought to escape the limitations and inconsistencies of the frequentist approach to probability theory [6][7]. Before that time, Bayesian methods were known under the name of inverse probability (because they often involve inferring causes from effects).

In the 20th century, the ideas of Laplace were further developed in two different directions, giving rise to the objective and subjective Bayesian schools. In the objectivists school, the statistical analysis depends only on the model assumed and the data analysed [8]. No subjective decisions need to be involved. In contrast, the subjectivist school denies the possibility of fully objective analysis for the general case.

In the further development of Laplace's ideas, the subjective school predates the objectivist school. The idea that 'probability' should be interpreted as 'subjective degree of belief in a proposition' was proposed by John Maynard Keynes in the early 1920s. This idea was taken further by Bruno de Finetti in Italy (Fondamenti Logici del Ragionamento Probabilistico, 1930) and Frank Ramsey in Cambridge (The Foundations of Mathematics, 1931).[9] The approach was devised to solve problems with the frequentist definition of probability but also with the earlier, objectivist approach of Laplace [10]. The subjective school was further developed and popularized in the 1950's by L.J. Savage.

The strong revival of objective Bayesian inference was mainly due to Harold Jeffreys, whose seminal book "Theory of probability" first appeared in 1939. In 1957, Edwin Jaynes introduced the concept of maximum entropy, which is an important principle in the formulation of objective methods, mainly for discrete problems. In 1979, José-Miguel Bernardo introduced reference analysis[11], which offers a general applicable framework for objective analysis.

In contrast to the frequentist view of probability, the Bayesian viewpoint has a well formulated axiomatic basis. In 1946, Richard T. Cox showed that the rules of Bayesian inference necessarily follow from a simple set of desiderata, including the representation of degrees of belief by real numbers and the need for consistency [2]. Another fundamental justification of the Bayesian approach is De Finetti's theorem, which was formulated in 1930 [12].

Other well-known proponents of Bayesian probability theory include I.J. Good, B.O. Koopman, Dennis Lindley, Howard Raiffa, Robert Schlaifer and Alan Turing.

In the 1980's, there was a dramatic growth in research and applications of Bayesian methods, mostly attributed to dramatic improvements in hardware and software, and an increasing interest in nonstandard, complex applications [13]. Despite the advantages of the Bayesian approach (such as a solid axiomatic basis and wider scope), most undergraduate teaching is still based on frequentist statistics, mainly due to academic inertia [14]. Nonetheless, Bayesian methods are widely accepted and used, such as for example in the field of machine learning [15].

[edit] Justification of the Bayesian view

There are three main ways in which the Bayesian view can be justified: the Cox axioms, the Dutch book argument and de Finetti's theorem.

Richard T. Cox showed that Bayesian inference is the only inductive inference that is logically consistent [2]. The rules of Bayesian inference necessary follow from some simple desiderata, such as consistency and the fact that a probability is expressed numerically. Both Cox and ET Jaynes promoted the view of Bayesian inference as an extension of Aristotelian logic.

[edit] Objective versus subjective Bayesian inference

Subjective Bayesian probability interprets 'probability' as 'the degree of belief (or strength of belief) an individual has in the truth of a proposition', and is in that respect subjective. In particular, they claim the choice of the prior is necessarily subjective.

Other Bayesians state that such subjectivity can be avoided, and claim that the prior state of knowledge uniquely defines a prior probability distribution for well posed problems. This was also the position taken in by the first followers of the Bayesian view, beginning with Laplace. In the Bayesian revival in the 20th century, the chief proponents of this objectivist school were Edwin Thompson Jaynes and Harold Jeffreys. More recently, James Berger (Duke University) and José-Miguel Bernardo (Universitat de València) have contributed to the development of objective Bayesian methods. For the objective construction of the prior distribution, the following principles can be applied:

[edit] Scientific method

The scientific method can be interpreted as an application of Bayesian probabilist inference [1]. In this view, Bayes' theorem is explicitly or implicitly used to update the strength of prior scientific beliefs in the truth of hypotheses in the light of new information from observation or experiment. ET Jaynes' book probability theory (which appeared posthumously in 2003) has the logic of science as subtitle, and argues for the scientific method as a form of Bayesian inference.

[edit] See also

- Bayesian inference: practical application of the Bayesian view

- Bayesian network: Bayesian reasoning for multiple variables in the presence of conditional independencies

- Bertrand's paradox: a paradox in classical probability, solved by Bayesian methods

- De Finetti's game: a procedure for evaluating someone's subjective probability

- Fiducial inference: Fisher's attempt to produce 'posterior' distributions without the use of a prior.

- Frequency probability: the main alternative to the Bayesian view

- Inference

- Maximum entropy thermodynamics: a Bayesian view of thermodynamics due to Edwin T. Jaynes

- Probability interpretations

- Uncertainty

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ a b c ET. Jaynes. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science Cambridge University Press, (2003). ISBN 0-521-59271-2

- ^ a b c Richard T. Cox, Algebra of Probable Inference, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001

- ^ de Finetti, B. (1974) Theory of probability (2 vols.), J. Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York

- ^ Bishop, CM., Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer, 2007

- ^ Stephen M. Stigler (1986) The history of statistics. Harvard University press. Chapter 3.

- ^ Jeff Miller, "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (B)"

- ^ Stephen. E. Fienberg, When did Bayesian Inference become "Bayesian"? Bayesian Analysis (2006).

- ^ JM. Bernardo (2005), Reference analysis, Handbook of statistics, 25, 17-90

- ^ Gillies, D. (2000), Philosophical Theories of Probability. (Routledge). See p50-1 "The subjective theory of probability was discovered independently and at about the same time by Frank Ramsey in Cambridge and Bruno de Finetti in Italy."

- ^ JM. Bernardo (2005), Reference analysis, Handbook of statistics, 25, 17-90

- ^ JM. Bernardo (2005), Reference analysis, Handbook of statistics, 25, 17-90

- ^ de Finetti, B. (1930), Funzione caratteristica di un fenomeno aleatorio. Mem. Acad. Naz. Lincei. 4, 86-133

- ^ Wolpert, RL. (2004) A conversation with James O. Berger, Statistical science, 9, 205-218

- ^ José M. Bernardo (2006) A Bayesian mathematical statistics prior. ICOTS-7

- ^ Bishop, CM., Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer, 2007

[edit] External links

- A tutorial on Bayesian probabilities

- A. Hajek and S. Hartmann: Bayesian Epistemology (review article)

- On-line textbook: Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms, by David MacKay, has many chapters on Bayesian methods, including introductory examples; arguments in favour of Bayesian methods (in the style of Edwin Jaynes); state-of-the-art Monte Carlo methods, message-passing methods, and variational methods; and examples illustrating the intimate connections between Bayesian inference and data compression.

- An Intuitive Explanation of Bayesian Reasoning A very gentle introduction by Eliezer Yudkowsky

- An on-line introductory tutorial to Bayesian probability from Queen Mary University of London

- Jaynes, E.T. (1998) Probability Theory : The Logic of Science.

- Bretthorst, G. Larry, 1988, Bayesian Spectrum Analysis and Parameter Estimation in Lecture Notes in Statistics, 48, Springer-Verlag, New York, New York;

- Jeff Miller "Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (B)"

- James Franklin The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability Before Pascal, history from a Bayesian point of view.

- Is the portrait of Thomas Bayes authentic? Who Is this gentleman? When and where was he born? The IMS Bulletin, Vol. 17 (1988), No. 3, pp. 276-278