Osteoarthritis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Osteoarthritis Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-10 | M15.-M19., M47. |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 715 |

| OMIM | 165720 |

| DiseasesDB | 9313 |

| MedlinePlus | 000423 |

| eMedicine | med/1682 orthoped/427 pmr/93 radio/492 |

| MeSH | D010003 |

Osteoarthritis (OA, also known as degenerative arthritis, degenerative joint disease), is a group of diseases and mechanical abnormalities entailing degradation of joints,[1] including articular cartilage and the subchondral bone next to it. Clinical symptoms of OA may include joint pain, tenderness, stiffness, inflammation, creaking, and locking of joints. In OA, a variety of potential forces -- hereditary, developmental, metabolic, and mechanical -- may initiate processes leading to loss of cartilage -- a strong protein matrix that lubricates and cushions the joints. As the body struggles to contain ongoing damage, immune and regrowth process can accelerate damage.[2] When bone surfaces become less well protected by cartilage, subchondral bone may be exposed and damaged, with regrowth leading to a proliferation of ivory-like, dense, reactive bone in central areas of cartilage loss, a process called eburnation.[3] The patient increasingly experiences pain upon weight bearing, including walking and standing. Due to decreased movement because of the pain, regional muscles may atrophy, and ligaments may become more lax.[4] OA is the most common form of arthritis,[4] and the leading cause of chronic disability in the United States.[5]

"Osteoarthritis" is derived from the Greek word "osteo", meaning "of the bone", "arthro", meaning "joint", and "itis", meaning inflammation, although many sufferers have little or no inflammation. A common misconception is that OA is due solely to wear and tear, since OA typically is not present in younger people. However, while age is correlated with OA incidence, this correlation merely illustrates that OA is a process that takes time to develop. There is usually an underlying cause for OA, in which case it is described as secondary OA. If no underlying cause can be identified it is described as primary OA. "Degenerative arthritis" is often used as a synonym for OA, but the latter involves both degenerative and regenerative changes.

OA affects nearly 27 million people in the United States, accounting for 25% of visits to primary care physicians, and half of all NSAID (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) prescriptions. It is estimated that 80% of the population will have radiographic evidence of OA by age 65, although only 60% of those will show symptoms.[6] In the United States, hospitalizations for osteoarthritis soared from about 322,000 in 1993 to 735,000 in 2006.[7]

Contents |

[edit] Signs and symptoms

The main symptom is acute pain, causing loss of ability and often stiffness. "Pain" is generally described as a sharp ache, or a burning sensation in the associated muscles and tendons. OA can cause a crackling noise (called "crepitus") when the affected joint is moved or touched, and patients may experience muscle spasm and contractions in the tendons. Occasionally, the joints may also be filled with fluid. Humid and cold weather increases the pain in many patients.[8][9]

OA commonly affects the hands, feet, spine, and the large weight bearing joints, such as the hips and knees, although in theory, any joint in the body can be affected. As OA progresses, the affected joints appear larger, are stiff and painful, and usually feel worse, the more they are used throughout the day, thus distinguishing it from rheumatoid arthritis.

In smaller joints, such as at the fingers, hard bony enlargements, called Heberden's nodes (on the distal interphalangeal joints) and/or Bouchard's nodes (on the proximal interphalangeal joints), may form, and though they are not necessarily painful, they do limit the movement of the fingers significantly. OA at the toes leads to the formation of bunions, rendering them red or swollen.

OA is the most common cause of water on the knee, an accumulation of excess fluid in or around the knee joint. [10]

[edit] Causes

Although it commonly arises from trauma, osteoarthritis often affects multiple members of the same family, suggesting that there is hereditary susceptibility to this condition. A number of studies have shown that there is a greater prevalence of the disease between siblings and especially identical twins, indicating a hereditary basis [11]. Up to 60% of OA cases are thought to result from genetic factors. Researchers are also investigating the possibility of allergies, infections, or fungi as a cause.

[edit] Two types?

OA affects nearly 21 million people in the United States, accounting for 25% of visits to primary care physicians, and half of all NSAID (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) prescriptions. It is estimated that 80% of the population will have radiographic evidence of OA by age 65, although only 60% of those will be symptomatic.[6] Some investigators believe that mechanical stress on joints underlies all osteoarthritis, with many and varied sources of mechanical stress, including misallignments of bones due to congenital or pathogenic causes; mechanical injury; being overweight; loss of strength in muscles supporting joints; and impairment of peripheral nerves, leading to sudden or uncoordinated movements that overstress joints.[12]

[edit] Primary

This type of OA is a chronic degenerative disorder related to but not caused by aging, as there are people well into their nineties who have no clinical or functional signs of the disease. As a person ages, the water content of the cartilage decreases due to a reduced proteoglycan content, thus causing the cartilage to be less resilient. Without the protective effects of the proteoglycans, the collagen fibers of the cartilage can become susceptible to degradation and thus exacerbate the degeneration. Inflammation of the surrounding joint capsule can also occur, though often mild (compared to that which occurs in rheumatoid arthritis). This can happen as breakdown products from the cartilage are released into the synovial space, and the cells lining the joint attempt to remove them. New bone outgrowths, called "spurs" or osteophytes, can form on the margins of the joints, possibly in an attempt to improve the congruence of the articular cartilage surfaces. These bone changes, together with the inflammation, can be both painful and debilitating.

[edit] Secondary

This type of OA is caused by other factors but the resulting pathology is the same as for primary OA:

- Congenital disorders, such as:the chronica; disease

- Congenital hip luxation

- People with abnormally-formed joints (e.g. hip dysplasia (human)) are more vulnerable to OA, as added stress is specifically placed on the joints whenever they move. [However, recent studies have shown that double-jointedness may actually protect the fingers and hand from osteoarthritis.]

- Cracking joints

- Diabetes.

- Inflammatory diseases (such as Perthes' disease), (Lyme disease), and all chronic forms of arthritis (e.g. costochondritis, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis). In gout, uric acid crystals cause the cartilage to degenerate at a faster pace.

- Injury to joints, as a result of an accident.

- A joint infection, e.g. from an injury.

- Hormonal disorders.

- Ligamentous deterioration or instability may be a factor.

- Obesity. Obesity puts added weight on the joints, especially the knees.

- Sports injuries, or similar injuries from exercise or work. Certain sports, such as running or football, put undue pressure on the knee joints. Injuries resulting in broken ligaments can lead to instability of the joint and over time to wear on the cartilage and eventually osteoarthritis.

- Pregnancy

- Alkaptonuria

- Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease

[edit] Diagnosis

Diagnosis is normally done through x-rays. This is possible because loss of cartilage, subchondral ("below cartilage") sclerosis, subchondral cysts from synovial fluid entering small microfractures under pressure, narrowing of the joint space between the articulating bones, and bone spur formation (osteophytes) - from increased bone turnover in this condition, show up clearly on x-rays. Plain films, however, often do not correlate well with the findings of physical examination of the affected joints.

With or without other techniques, such as MRI (magnetic resonance imaging), arthrocentesis and arthroscopy, diagnosis can be made by a careful study of the duration, location, the character of the joint symptoms, and the appearance of the joints themselves. As yet, there are no methods available to detect OA in its early and potentially treatable stages.

In 1990, the College of Rheumatology, using data from a multi-center study, developed a set of criteria for the diagnosis of hand osteoarthritis based on hard tissue enlargement and swelling of certain joints. These criteria were found to be 92% sensitive and 98% specific for hand osteoarthritis versus other entities such as rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropities [13].

Related pathologies whose names may be confused with osteoarthritis include pseudo-arthrosis. This is derived from the Greek words pseudo, meaning "false", and arthrosis, meaning "joint." Radiographic diagnosis results in diagnosis of a fracture within a joint, which is not to be confused with osteoarthritis which is a degenerative pathology affecting a high incidence of distal phalangeal joints of female patients.

[edit] Treatment

Generally speaking, the process of clinically detectable osteoarthritis is irreversible, and typical treatment consists of medication or other interventions that can reduce the pain of OA and thereby improve the function of the joint.

[edit] Conservative care

No matter the severity or location of OA, conservative measures such as weight control, appropriate rest and exercise, and the use of mechanical support devices are usually beneficial. In OA of the knees a knee braces can be helpful. A cane, or a walker can reduce pressure on involved leg joints which can be helpful for walking and support. Regular exercise, if possible, in the form of walking or swimming, or other low impact activities are encouraged. Applying local heat before, and cold packs after exercise, can help relieve pain and inflammation, as can relaxation techniques. Heat — often moist heat may improve circulation, which has a healing effect on the local area before activity, but should be followed by cryo-therapy (cold packs should not be used on any injury or area of swelling for more than 10-12 minutes at a time, waiting 20 minutes to reapply) to reduce the inflammation. Weight loss can relieve joint stress and may delay progression (Prevention suggestion cited here)[citation needed]. Proper advice and guidance by health care providers such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, and medical doctors is important in OA management, enabling people with this condition to improve their quality of life.

In 2002, a randomized, blinded assessor trial was published showing a positive effect on hand function with patients who practiced home joint protection exercises (JPE). Grip strength, the primary outcome parameter, increased by 25% in the exercise group versus no improvement in the control group. Global hand function improved by 65% for those undertaking JPE. [14]

[edit] Medical treatment

Implantation may be a possible treatment.[15] Clinical trials currently employ tissue that is strong and able to lubricate joints. The chondrocytes are implanted into an area of damaged cartilage, and must be protected as they integrate into the joint, typically in a strong, biocompatible, biodegradeable scaffolding that allows for growth factors to stimulate cartilage production. As new cartilage is produced, the scaffolding is absorbed. [16]

[edit] Dietary

Supplements which may be useful for treating OA include:

[edit] Glucosamine

There is still controversy about glucosamine's effectiveness for OA of the knee.[17] A 2005 review concluded that glucosamine may improve symptoms of OA and delay its progression.[18] However, a subsequent large study suggests that glucosamine is not effective in treating OA of the knee[19], and a 2007 meta-analysis that included this trial states that glucosamine hydrochloride is not effective.[20]

[edit] Chondroitin

Along with glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate has become a widely used dietary supplement for treatment of osteoarthritis. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found no benefit from chondroitin.[21] However, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International is in support of the use of chondroitin sulfate for OA.[citation needed]

[edit] Other supplements

- Omega-3 fatty acid,a vitamin supplement composed of important oils derived from fish.[citation needed]

- Frankincense resin from trees in the genus Boswellia. In Ayurvedic medicine, Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata) has been used for hundreds of years for treating arthritis.[22]

- Bromelain, protease enzymes extracted from the plant family Bromeliaceae (pineapple), blocks some proinflammatory metabolites.[23]

- Antioxidants, including vitamins C and E in both foods and supplements, provide pain relief from OA.[24]

- Hydrolyzed collagen (hydrolysate) (a gelatin product) may also prove beneficial in the relief of OA symptoms, as substantiated in a German study by Beuker F. et al. and Seeligmuller et al. In their 6-month placebo-controlled study of 100 elderly patients, the verum group showed significant improvement in joint mobility.[citation needed]

- Vitamin B9 (folate) and B12 (cobalamin) taken in large doses has been thought to reduce OA hand pain in one very small, non-quantitative study of 25 people, the results of which are extremely vague at best.[27] The risk from large doses would suggest that this is not a safe treatment.

- Vitamin D deficiency has been reported in patients with OA, and supplementation with Vitamin D3 is recommended for pain relief.[28]

- Bone Morphogenetic Protein 6 (BMP-6) has recently been shown to have a functional role in the maintenance of joint integrity and is now being produced in an orally ingested form. [29]

Other nutritional changes shown to aid in the treatment of OA include decreasing saturated fat intake[30] and using a low energy diet to decrease body fat.[31] Lifestyle change may be needed for effective symptomatic relief, especially for knee OA.[32]

[edit] Complications

Dealing with chronic pain can be difficult and result in depression. Communicating with other patients and caregivers can be helpful, as can maintaining a positive attitude. People who take control of their treatment, communicate with their health care provider, and actively manage their arthritis experience can reduce pain and improve function.[citation needed]

[edit] Specific medications

[edit] Paracetamol

A mild pain reliever may be sufficiently efficacious. Paracetamol (tylenol/acetaminophen), is commonly used to treat the pain from OA. A randomized controlled trial comparing paracetamol with ibuprofen in x-ray-proven mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the hip or knee found equal benefit.[33] However, paracetamol at a dose of 4 grams per day can increase liver function tests.[34]

[edit] Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

In more severe cases, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) may reduce both the pain and inflammation; they all act by inhibiting the formation of prostaglandins, which play a central role in inflammation and pain. Most prominent drugs in the class include diclofenac, ibuprofen, naproxen and ketoprofen. High oral drug doses are often required. However, diclofenac has been found to cause damage to the articular cartilage. Even more importantly all systemic NSAIDs are rather taxing on the gastrointestinal tract, and may cause stomach upset, cramping, diarrhea, and peptic ulcer. Such systemic adverse side effects are normally not observed when using NSAIDs topically, that is, on the skin around the target area. The typically weak and/or short-lived therapeutic effect of such topical treatments may be improved by using the drug in more modern formulations, including or ketoprofen associated with the Transfersome carriers or diclofenac in DMSO solution.

[edit] COX-2 selective inhibitors

Another type of NSAID, COX-2 selective inhibitors (such as celecoxib, and the withdrawn rofecoxib and valdecoxib) reduce this risk substantially. These latter NSAIDs carry an elevated risk for cardiovascular disease, and some have now been withdrawn from the market.

[edit] Corticosteroids

Most doctors nowadays avoid the use of steroids in the treatment of OA as their effect is modest and the adverse effects may outweigh the benefits. However intra - articular corticosteroid injections help severe symptoms temporarily.

[edit] Narcotics

For moderate to severe pain, narcotic pain relievers such as tramadol, and eventually opioids (hydrocodone, oxycodone or morphine) may be necessary.

[edit] Topical

"Topical treatments" are treatments designed for local application and action. There are several NSAIDs available for topical use (e.g. diclofenac, ibuprofen, and ketoprofen) with little, if any, systemic side-effects and at least some therapeutic effect. The more modern NSAID formulations for direct use, containing the drugs in an organic solution or the Transfersome carrier based gel, reportedly, are as effective as oral NSAIDs.

Creams and lotions, containing capsaicin, are effective in treating pain associated with OA if they are applied with sufficient frequency.

Severe pain in specific joints can be treated with local lidocaine injections or similar local anaesthetics, and glucocorticoids (such as hydrocortisone). Corticosteroids (cortisone and similar agents) may temporarily reduce the pain. Certain anti-inflammatory medications, such as dexamethasone, can also be used in a procedure called iontophoresis, which uses mild electrical current to transfer the medication through the skin.

Transdermal glucosamine cream is another type of topical treatment that can help with degenerated cartilage. Unlike pain relieving medications which help to alleviate pain only, transdermal glucosamine cream containing glucosamine sulphate salt[1] can help to repair and regenerate cartilage. There are superior transdermal glucosamine cream available that can deliver glucosamine into the body for treatment of degenerated cartilage.

[edit] Surgery

If the above management is ineffective, joint replacement surgery may be required. Individuals with very painful OA joints may require surgery such as fragment removal, repositioning bones, or fusing bone to increase stability and reduce pain. Arthroscopic surgical intervention for osteoarthritis of the knee may be no better than placebo at relieving symptoms.[35]

[edit] Chiropractic

The American Chiropractic Association[36] urges its practitioners to check for early signs of degenerative changes in the joints, including the spine, hips, knees, and other weight-bearing joints. Practitioners are trained to relieve pain and improve joint function through natural therapies, including chiropractic manipulation, trigger point therapy, and massage techniques. They may also offer exercise counseling and suggest dietary supplements or pain-relief options -- such as applying heat or cold to the affected area.

[edit] Acupuncture

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture for knee osteoarthritis concluded "clinically relevant benefits, some of which may be due to placebo or expectation effects".[37]

[edit] Prognosis

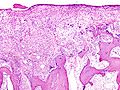

[edit] Additional images

|

Examples of damaged cartilage in gross pathological specimen from sows. (a) cartilage erosion (b) cartilage ulceration (c) cartilage repair (d) osteophyte (bone spur) formation. |

|||

[edit] See also

- Arthritis

- Articular cartilage repair

- Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

- Back pain

- Chronic pain

- Osteoimmunology

- Prolotherapy

- Partial knee replacement

- Arthritis Care

- Rheumatoid arthritis

[edit] References

- ^ osteoarthritis at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Brandt, Kenneth D.; Dieppe, Paul; Radin, Eric (2008), "Etiopathogenesis of Osteoarthritis", Med Clin N Am 93: 1–24, doi:

- ^ Siddiqui, Furqan (2008-9-12). "Osteoarthritis". Emedicine. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1270114-overview. Retrieved on 2009-01-27.

- ^ a b Conaghan, Phillip. "Osteoarthritis - National clinical guideline for care and management in adults" (PDF). http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG059FullGuideline.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-04-29.

- ^ "Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999". MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 50 (7): 120–5. February 2001. PMID 11393491.

- ^ a b Green GA (2001). "Understanding NSAIDs: from aspirin to COX-2". Clin Cornerstone 3 (5): 50–60. PMID 11464731.

- ^ Hospitalizations for Osteoarthritis Rising Sharply Newswise, Retrieved on September 4, 2008.

- ^ McAlindon, T., Formica, M., Schmid, C.H., & Fletcher, J. (2007). Changes in barometric pressure and ambient temperature influence osteoarthritis pain. The American Journal of Medicine, 120(5), 429-434.

- ^ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Osteoarthritis

- ^ Water on the knee, MayoClinic.com

- ^ Valdes AM, Spector TD (August 2008). "The contribution of genes to osteoarthritis". Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 34 (3): 581–603. doi:. PMID 18687274.

- ^ Brandt, K.D.; Dieppe, P.; Radin, E. (2009), "Etiopathogenesis of osteoarthritis", Med Clin North Am. 93 (1): 1–24, doi:, PMID 19059018

- ^ Altman R, Alarcón G, Appelrouth D, et al (1990). "The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand". Arthritis Rheum. 33 (11): 1601–10. doi:. PMID 2242058.

- ^ Stamm TA, Machold KP, Smolen JS, et al (2002). "Joint protection and home hand exercises improve hand function in patients with hand osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial". Arthritis Rheum. 47 (1): 44–9. doi:. PMID 11932877.

- ^ Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

- ^ Klein, Jacob (2009), "CHEMISTRY: Repair or Replacement--A Joint Perspective", Science 323 (5910): 47–48, doi:, PMID 19119205

- ^ "The effects of Glucosamine Sulphate on OA of the knee joint". http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=979.

- ^ Poolsup N, Suthisisang C, Channark P, Kittikulsuth W (2005). "Glucosamine long-term treatment and the progression of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review of randomized controlled trials". The Annals of pharmacotherapy 39 (6): 1080–7. doi:. PMID 15855241.

- ^ McAlindon T, Formica M, LaValley M, Lehmer M, Kabbara K (November 2004). "Effectiveness of glucosamine for symptoms of knee osteoarthritis: results from an internet-based randomized double-blind controlled trial". Am J Med 117 (9): 643–9. doi:. PMID 15501201.

- ^ Vlad SC, Lavalley MP, McAlindon TE, Felson DT (2007). "Glucosamine for pain in osteoarthritis: Why do trial results differ?". Arthritis & Rheumatism 56 (7): 2267–77. doi:. PMID 17599746.

- ^ Reichenbach S, Sterchi R, Scherer M, et al (2007). "Meta-analysis: chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (8): 580–90. PMID 17438317.

- ^ "JOINT RELIEF". www.herbcompanion.com. http://www.herbcompanion.com/health/JOINT-RELIEF.aspx?page=2. Retrieved on 2009-01-12.

- ^ Brien S, Lewith G, Walker A (2004). "Bromelain as a Treatment for Osteoarthritis: a Review of Clinical Studies". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 1 (3): 251–257. doi:. PMID 15841258.

- ^ McAlindon TE, Jacques P, Zhang Y, et al (1996). "Do antioxidant micronutrients protect against the development and progression of knee osteoarthritis?". Arthritis Rheum. 39 (4): 648–56. PMID 8630116.

- ^ Altman RD, Marcussen KC (2001). "Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis". Arthritis Rheum. 44 (11): 2531–8. PMID 11710709.

- ^ "UNC News release -- Study links low selenium levels with higher risk of osteoarthritis". http://www.unc.edu/news/archives/nov05/jordan111005.htm. Retrieved on 2007-06-22.

- ^ Flynn MA, Irvin W, Krause G (1994). "The effect of folate and cobalamin on osteoarthritic hands". J Am Coll Nutr 13 (4): 351–6. PMID 7963140.

- ^ Arabelovic S, McAlindon TE (2005). "Considerations in the treatment of early osteoarthritis". Curr Rheumatol Rep 7 (1): 29–35. PMID 15760578.

- ^ Bobacz K, Gruber R, Soleiman A, Erlacher L, Smolen JS, Graninger WB (2003). "Expression of bone morphogenetic protein 6 in healthy and osteoarthritic human articular chondrocytes and stimulation of matrix synthesis in vitro". Arthritis Rheum. 48 (9): 2501–8. doi:. PMID 13130469.

- ^ Wilhelmi G. Z Rheumatol. 1993 May-Jun; 52(3):174-9. Vasishta VG et al, Rotational Field Magnetic Resonance (RFQMR) in treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee joint, Indian Journal of Aerospace Medicine, 48 (2), 2004; 1-7.

- ^ Christensen R, Astrup A, Bliddal H (2005). "Weight loss: the treatment of choice for knee osteoarthritis? A randomized trial". Osteoarthr. Cartil. 13 (1): 20–7. doi:. PMID 15639633. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1063-4584(04)00203-1.

- ^ De Filippis L, Gulli S, Caliri A, et al (2004). "[Epidemiology and risk factors in osteoarthritis: literature review data from "OASIS" study]" (in Italian) (PDF). Reumatismo 56 (3): 169–84. PMID 15470523. http://www.reumatismo.org/admin/filesArticoli/56-3-169.pdf.

- ^ Bradley JD, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Kalasinski LA, Ryan SI (1991). "Comparison of an antiinflammatory dose of ibuprofen, an analgesic dose of ibuprofen, and paracetamol in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee". N. Engl. J. Med. 325 (2): 87–91. PMID 2052056.

- ^ Watkins PB, Kaplowitz N, Slattery JT, et al (2006). "Aminotransferase elevations in healthy adults receiving 4 grams of acetaminophen daily: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA 296 (1): 87–93. doi:. PMID 16820551.

- ^ Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, et al (July 2002). "A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee". N. Engl. J. Med. 347 (2): 81–8. doi:. PMID 12110735. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/347/2/81.

- ^ http://www.acatoday.org/content_css.cfm?CID=1465

- ^ Manheimer E, Linde K, Lao L, Bouter LM, Berman BM (2007). "Meta-analysis: acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (12): 868–77. doi:. PMID 17577006.

[edit] External links

- American College of Rheumatology Factsheet on OA

- Osteoarthritis The Arthritis Foundation

- WebMDHealth: Osteoarthritis Basics at WebMD

- [2] American Chiropractic Association

|

|||||||||||||||||||||