Partition of India

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Colonial India |

|||||

| Portuguese India | 1510–1961 | ||||

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 | ||||

| Danish India | 1696–1869 | ||||

| French India | 1759–1954 | ||||

| British Empire in India |

|||||

| East India Company | 1612–1757 | ||||

| Company rule in India | 1757–1857 | ||||

| British Raj | 1858–1947 | ||||

| British rule in Burma | 1826–1948 | ||||

| British India | 1612–1947 | ||||

| Princely states | 1765–1947 | ||||

| Partition of India | 1947 | ||||

|

|

|||||

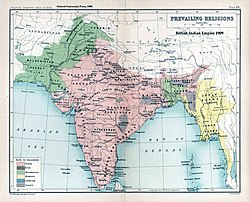

The Partition of India was the partition of British India that led to the creation, on August 14, 1947 and August 15, 1947, respectively, of the sovereign states of the Dominion of Pakistan (later Islamic Republic of Pakistan and People's Republic of Bangladesh) and the Union of India (later Republic of India). The partition of India included the geographical division of the Bengal province of British India into East Pakistan and West Bengal (India), and the similar partition of the Punjab province into West Punjab (later Punjab (Pakistan) and Islamabad Capital Territory) and East Punjab (later Punjab (India), Haryana and Himachal Pradesh), and also the division of other assets, including the British Indian Army, the Indian Civil Service and other administrative services, the Indian railways, and the central treasury. The partition was promulgated in the Indian Independence Act 1947 and resulted in the dissolution of the British Indian Empire.

In the aftermath of Partition, the princely states of India, which had been left by the Indian Independence Act 1947 to choose whether to accede to India or Pakistan or to remain outside them,[1] were all incorporated into one or other of the new dominions. The question of the choice to be made in this connection by Jammu and Kashmir led to the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 and other wars and conflicts between India and Pakistan.[2]

The secession of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971 is not covered by the term Partition of India, nor is the earlier separation of Burma from the administration of British India, or the even earlier separation of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Ceylon, part of the Madras Presidency of British India from 1795 until 1798, became a separate Crown Colony in 1798. Burma, gradually annexed by the British during 1826–86 and governed as a part of the British Indian administration until 1937, was directly administered thereafter. [3] Burma was granted independence on January 4, 1948 and Ceylon on February 4, 1948. (See History of Sri Lanka and History of Burma) The Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861, however, the issue of sovereignty was left undefined.[4] In 1947, Sikkim became an independent kingdom under the suzerainty of India and remained so until 1975 when it was absorbed into India as the 22nd state.

The remaining countries of present-day South Asia are Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives. The first two, Nepal and Bhutan, having signed treaties with the British designating them as independent states, were never a part of British India, and therefore their borders were not affected by the partition.[5] The Maldives, which became a protectorate of the British crown in 1887 and gained its independence in 1965, was also unaffected by the partition.

The partition displaced up to 12.5 million people in the former British Indian Empire with estimates of loss of life varying from several hundred thousand to a million.[6]

Contents |

Pakistan and India

Two self governing countries legally came into existence at the stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947. The ceremonies for the transfer of power were held a day earlier in Karachi, at the time the capital of the new state of Pakistan, so that the last British Viceroy, Louis Mountbatten, could attend both the ceremony in Karachi as well as the ceremony in Delhi. However another reason for this arrangement was to avoid the appearance that Pakistan was seceding from a sovereign India. Therefore Pakistan celebrates Independence Day on August 14, while India celebrates it on August 15.

Another reason for Pakistan celebrating independence on August 14 is the adoption of new standard time in Pakistan after partition.[citation needed] The new standard time of West Pakistan (modern 'Pakistan') was behind Indian standard time by 30 minutes and the new standard time of East Pakistan (modern 'Bangladesh') was ahead of Indian standard time by 30 minutes, so technically on the stroke of midnight falling between August 14 and 15, when India "got independence", it was still 11:30 PM on 14 August in West Pakistan.

Background

Late 19th and early 20th century

1920–1932

The All India Muslim League (AIML) was formed in Dhaka in 1906 by Muslims who were suspicious of the Hindu-majority Indian National Congress. They complained that they were not given same rights as a Muslim member compared to Hindu members. A number of different scenarios were proposed at various times. Among the first to make the demand for a separate state was the writer/philosopher Allama Iqbal, who, in his presidential address to the 1930 convention of the Muslim League said that he felt a separate nation for Muslims was essential in an otherwise Hindu-dominated subcontinent. The Sindh Assembly passed a resolution making it a demand in 1935. Iqbal, Jouhar and others then worked hard to draft Mohammad Ali Jinnah, who had till then worked for Hindu-Muslim unity, to lead the movement for this new nation. By 1930, Jinnah had begun to despair of the fate of minority communities in a united India and had begun to argue that mainstream parties such as the Congress, of which he was once a member, were insensitive to Muslim interests. The 1932 communal award which seemed to threaten the position of Muslims in Hindu-majority provinces catalysed the resurgence of the Muslim League, with Jinnah as its leader. However, the League did not do well in the 1937 provincial elections, demonstrating the hold of the conservative and local forces at the time.

1932–1942

In 1940, Jinnah made a statement at the Lahore conference, which seemed to be calling for a separate Muslim 'nation'. However, the document was ambiguous and opaque, and did not evoke a Muslim nation in a territorial sense. This idea, though, was taken up by Muslims and particularly Hindus in the next seven years, and given a more territorial element. All Muslim political parties including the Khaksar Tehrik of Allama Mashriqi (Mashriqi was arrested on March 19, 1940) opposed the partition of India[7]

Hindu organisations such as the Hindu Mahasabha, though against the division of the country, were also insisting on the same chasm between Hindus and Muslims. In 1937 at the 19th session of the Hindu Mahasabha held at Ahmedabad, Veer Savarkar in his presidential address asserted:[8]

| “ | India cannot be assumed today to be Unitarian and homogeneous nation, but on the contrary there are two nations in the main — the Hindus and the Muslims. | ” |

Most of the Congress leaders were secularists and resolutely opposed the division of India on the lines of religion. Mohandas Gandhi and Allama Mashriqi believed that Hindus and Muslims could and should live in amity. Gandhi opposed the partition, saying,

| “ | My whole soul rebels against the idea that Hinduism and Islam represent two antagonistic cultures and doctrines. To assent to such a doctrine is for me a denial of God. | ” |

For years, Gandhi and his adherents struggled to keep Muslims in the Congress Party (a major exit of many Muslim activists began in the 1930s), in the process enraging both Hindu Nationalists and Indian Muslim Nationalists. (Gandhi was assassinated soon after Partition by Hindu Nationalist Nathuram Godse, who believed that Gandhi was appeasing Muslims at the cost of Hindus.) Politicians and community leaders on both sides whipped up mutual suspicion and fear, culminating in dreadful events such as the riots during the Muslim League's Direct Action Day of August 1946 in Calcutta, in which more than 5,000 people were killed and many more injured. As public order broke down all across northern India and Bengal, the pressure increased to seek a political partition of territories as a way to avoid a full-scale civil war.

1942–1946

Until 1946, the definition of Pakistan as demanded by the League was so flexible that it could have been interpreted as a sovereign nation Pakistan, or as a member of a confederated India.

Some historians believe Jinnah intended to use the threat of partition as a bargaining chip in order to gain more independence for the Muslim dominated provinces in the west from the Hindu dominated center.[9]

Other historians claim that Jinnah's real vision was for a Pakistan that extended into Hindu-majority areas of India, by demanding the inclusion of the East of Punjab and West of Bengal, including Assam, a Hindu-majority country. Jinnah also fought hard for the annexation of Kashmir, a Muslim majority state with Hindu ruler; and the accession of Hyderabad and Junagadh, Hindu-majority states with Muslim rulers.[citation needed]

The British colonial administration did not directly rule all of "India". There were several different political arrangements in existence: Provinces were ruled directly and the Princely States with varying legal arrangements, like paramountcy.

The British Colonial Administration consisted of Secretary of State for India, the India Office, the Governor-General of India, and the Indian Civil Service.

The Indian Political Parties were (alphabetically) All India Muslim League, Communist Party of India, Hindu Mahasabha, Indian National CongressKhaksar Tehrik, and the Unionist Muslim League (mainly in the Punjab).

The Partition: 1947

Mountbatten Plan

The actual division between the two new dominions was done according to what has come to be known as the 3 June Plan or Mountbatten Plan.

The border between India and Pakistan was determined by a British Government-commissioned report usually referred to as the Radcliffe Line after the London lawyer, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who wrote it. Pakistan came into being with two non-contiguous enclaves, East Pakistan (today Bangladesh) and West Pakistan, separated geographically by India. India was formed out of the majority Hindu regions of the colony, and Pakistan from the majority Muslim areas.

On July 18, 1947, the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act that finalized the partition arrangement. The Government of India Act 1935 was adapted to provide a legal framework for the two new dominions. Following partition, Pakistan was added as a new member of the United Nations. The union formed from the combination of the Hindu states assumed the name India which automatically granted it the seat of British India (a UN member since 1945) as a successor state.[10]

The 625 Princely States were given a choice of which country to join.

Geography of the partition: the Radcliffe Line

The Punjab — the region of the five rivers east of Indus: Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej — consists of interfluvial doabs, or tracts of land lying between two confluent rivers. These are the Sind-Sagar doab (between Indus and Jhelum), the Jech doab (Jhelum/Chenab), the Rechna doab (Chenab/Ravi), the Bari doab (Ravi/Beas), and the Bist doab (Beas/Sutlej) (see map). In early 1947, in the months leading up to the deliberations of the Punjab Boundary Commission, the main disputed areas appeared to be in the Bari and Bist doabs, although some areas in the Rechna doab were claimed by the Congress and Sikhs. In the Bari doab, the districts of Gurdaspur, Amritsar, Lahore, and Montgomery were all disputed.[11] All districts (other than Amritsar, which was 46.5% Muslim) had Muslim majorities; albeit, in Gurdaspur, the Muslim majority, at 51.1%, was slender. At a smaller area-scale, only three tehsils (sub-units of a district) in the Bari doab had non-Muslim majorities. These were: Pathankot (in the extreme north of Gurdaspur, which was not in dispute), and Amritsar and Tarn Taran in Amritsar district. In addition, there were four Muslim-majority tehsils east of Beas-Sutlej (with two where Muslims outnumbered Hindus and Sikhs together).[11]

Before the Boundary Commission began formal hearings, governments were set up for the East and the West Punjab regions. Their territories were provisionally divided by "notional division" based on simple district majorities. In both the Punjab and Bengal, the Boundary Commission consisted of two Muslim and two non-Muslim judges with Sir Cyril Radcliffe as a common chairman.[11] The mission of the Punjab commission was worded generally as: "To demarcate the boundaries of the two parts of the Punjab, on the basis of ascertaining the contiguous majority areas of Muslims and non-Muslims. In doing so, it will take into account other factors." Each side (the Muslims and the Congress/Sikhs) presented its claim through counsel with no liberty to bargain. The judges too had no mandate to compromise and on all major issues they "divided two and two, leaving Sir Cyril Radcliffe the invidious task of making the actual decisions."[11]

Independence and population exchanges

Massive population exchanges occurred between the two newly-formed states in the months immediately following Partition. Once the lines were established, about 14.5 million people crossed the borders to what they hoped was the relative safety of religious majority. Based on 1951 Census of displaced persons, 7,226,000 Muslims went to Pakistan from India while 7,249,000 Hindus and Sikhs moved to India from Pakistan immediately after partition. About 11.2 million or 78% of the population transfer took place in the west, with Punjab accounting for most of it; 5.3 million Muslims moved from India to West Punjab in Pakistan, 3.4 million Hindus and Sikhs moved from Pakistan to East Punjab in India; elsewhere in the west 1.2 million moved in each direction to and from Sind.[citation needed]

The newly formed governments were completely unequipped to deal with migrations of such staggering magnitude, and massive violence and slaughter occurred on both sides of the border. Estimates of the number of deaths range around roughly 500,000, with low estimates at 200,000 and high estimates at 1,000,000.[12]

Punjab

| This section requires expansion. |

The Indian state of Punjab was created in 1947, when the Partition of India split the former Raj province of Punjab between India and Pakistan. The mostly Muslim western part of the province became Pakistan's Punjab Province; the mostly Sikh and Hindu eastern part became India's Punjab state. Many Hindus and Sikhs lived in the west, and many Muslims lived in the east, and so the partition saw many people displaced and much intercommunal violence. Lahore and Amritsar were at the center of the problem, the British were not sure where to place them - make them part of India or Pakistan. The British did make a decision to hand both cities to India, but due to lack of control and regulation for the border Amritsar became part of India whilst Lahore became part of Pakistan. Areas in west Punjab such as Lahore, Rawalpindi, Multan, Gujart, had a large Sikh population and many of the resident were either attacked or killed by radical Muslims.[citation needed] On the other side in East Punjab cities such as Amritsar, Ludhiana, and Gurdaspur had a majority Muslim population in which many of them were wiped out by Sikh guerrillas who launched an all out war against the Muslims.

Bengal

The province of Bengal was divided into the two separate entities of West Bengal belonging to India, and East Bengal belonging to Pakistan. East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan in 1955, and later became the independent nation of Bangladesh after the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

Sindh

| Please help improve this article or section by expanding it. Further information might be found on the talk page. (November 2007) |

Hindu Sindhis were expected to stay in Sindh following Partition, as there were good relations between Hindu and Muslim Sindhis. At the time of Partition there were 1,400,000 Hindu Sindhis, though most were concentrated in the cities such as Hyderabad, Karachi, Shikarpur, and Sukkur. However, due to an uncertain future in a Muslim country, a sense of better opportunities in India, and most of all a sudden influx of Muslim refugees from Gujarat, UP, Bihar, Rajputana (Rajasthan) and other parts of India, many Sindhi Hindus decided to leave for India. Problems were further aggravated when incidents of violence instigated by Indian Muslim refugees broke out in Karachi and Hyderabad. As per the census of India 1951, nearly 776,000 Sindhi Hindus had poured into India.[13] Unlike the Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs, Sindhi Hindus did not have to witness any massive scale rioting; however, their entire province had gone to Pakistan thus they felt like a homeless community. Despite this migration, a significant Sindhi Hindu population still resides in Pakistan's Sindh province where they number at around 2.28 million as per Pakistan's 1998 census while the Sindhi Hindus in India as per 2001 census of India were at 2.57 million.[citation needed]

Perspectives

The Partition was a highly controversial arrangement, and remains a cause of much tension on the subcontinent today. British Viceroy Louis Mountbatten has not only been accused of rushing the process through, but also is alleged to have influenced the Radcliffe Line in India's favour since everyone agreed India would be a more desirable country for most.[14] [15] However, the commission took so long to decide on a final boundary that the two nations were granted their independence even before there was a defined boundary between them. Even then, the members were so distraught at their handiwork (and its results) that they refused compensation for their time on the commission.[citation needed]

Some critics allege that British haste led to the cruelties of the Partition.[16] Because independence was declared prior to the actual Partition, it was up to the new governments of India and Pakistan to keep public order. No large population movements were contemplated; the plan called for safeguards for minorities on both sides of the new state line. It was an impossible task, at which both states failed. There was a complete breakdown of law and order; many died in riots, massacre, or just from the hardships of their flight to safety. What ensued was one of the largest population movements in recorded history. According to Richard Symonds[17]

| “ | at the lowest estimate, half a million people perished and twelve million became homeless | ” |

However, some argue that the British were forced to expedite the Partition by events on the ground.[18] Law and order had broken down many times before Partition, with much bloodshed on both sides. A massive civil war was looming by the time Mountbatten became Viceroy. After World War II, Britain had limited resources, [19] perhaps insufficient to the task of keeping order. Another view point is that while Mountbatten may have been too hasty he had no real options left and achieved the best he could under difficult circumstances.[20] Historian Lawrence James concurs that in 1947 Mountbatten was left with no option but to cut and run. The alternative seemed to be involvement in a potentially bloody civil war from which it would be difficult to get out.[21]

Conservative elements in England consider the partition of India to be the moment that the British Empire ceased to be a world power, following Curzon's dictum that "While we hold on to India, we are a first-rate power. If we lose India, we will decline to a third-rate power." The 'flick' of the pen with which Clement Atlee signed the independence treaty is, where remembered, considered sadly; not for the loss of India, but for the loss of what holding India meant.

Delhi Punjabi refugees

An estimated 25 million people - Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs -(1947-present) crossed the newly carved borders to reach their new homelands. These estimates are based on comparisons of decadal censuses from 1941 and 1951 with adjustments for normal population growth in the areas of migration. In northern India - undivided Punjab and North Western Frontier Province (NWFP) - nearly 12 million were forced to move from as early as March 1947 following the Rawalpindi violence. Delhi received the highest number of refugees for a single city - the population of Delhi grew rapidly in 1947 from under 1 million (917.939) to a little less than 2 million (1.744.072) between the period 1941-1951.(Census of India, 1941 and 1951). The refugees were housed in various historical and military locations such as the Old Fort Purana Qila), Red Fort (Red Fort), and military barracks in Kingsway (around the present Delhi university). The latter became the site of one of the largest refugee camps in northern India with more than 35,000 refugees at any given time besides Kurukshetra camp near Panipat. The camp sites were later converted into permanent housing through extensive building projects undertaken by the Government of India from 1948 onwards. A number of housing colonies in Delhi came up around this period like Lajpat Nagar, Rajinder Nagar, Nizamuddin, Punjabi Bagh, Rehgar Pura, Jungpura and Kingsway. A number of schemes such as provision of education, employment opportunities, easy loans to start businesses etc. were provided for the refugees at all-India level. The Delhi refugees, however, were able to make use of these facilities much better than their counterparts elsewhere.[22]

Refugees settled in India

Many Sikhs and Hindu Punjabis settled in the Indian parts of Punjab and Delhi. Hindus migrating from East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) settled across Eastern India and Northeastern India, many ending up in close-by states like West Bengal, Assam, and Tripura. Some migrants were sent to the Andaman islands.

Hindu Sindhis found themselves without a homeland. The responsibility of rehabilitating them was borne by their government. Refugee camps were set up for Hindu Sindhis. However, non-Sindhi Hindus received little help from the Government of India, and many never received compensation of any sort from the Indian Government.

Many refugees overcame the trauma of poverty, though the loss of a homeland has had a deeper and lasting effect on their Sindhi culture.

In late 2004, the Sindhi diaspora vociferously opposed a Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India which asked the government of India to delete the word "Sindh" from the Indian National Anthem (written by Rabindranath Tagore prior to the partition) on the grounds that it infringed upon the sovereignty of Pakistan.

Refugees settled in Pakistan

Refugees or Muhajirs in Pakistan came from various parts of India. There was a large influx of Punjabi Muslims from East Punjab fleeing the riots. Despite severe physical and economic hardships, East Punjabi refugees to Pakistan did not face problems of cultural and linguistic assimilation after partition. However, there were many Muslim refugees who migrated to Pakistan from other Indian states. These refugees came from many different ethnic groups and regions in India, including Rajasthan Uttar Pradesh (then known as "United Provinces of Agra and Awadh", or UP), Madhya Pradesh (then Central Province or "CP"), Gujarat, Bihar, what was then the princely state of Hyderabad and so on. The descendants of these non-Punjabi refugees in Pakistan often refer to themselves as Muhajir whereas the assimilated Punjabi refugees no longer make that political distinction. Large numbers of non-Punjabi refugees settled in Sindh, particularly in the cities of Karachi and Hyderabad. They are united by their refugee status and their native Urdu language and are a strong political force in Sindh.

Artistic depictions of the Partition

In addition to the enormous historical literature on the Partition, there is also an extensive body of artistic work (novels, short stories, poetry, films, plays, paintings, etc.) that deals imaginatively with the pain and horror of the event.

See also

- Indian reunification

- British East India Company

- British India

- List of Indian Princely States

- Indian independence movement

- Pakistan Movement

- East Bengal

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

- History of Pakistan

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

- India (disambiguation)

References

- ^ Revised Statute from The UK Statute Law Database: Indian Independence Act 1947 (c.30) at opsi.gov.uk

- ^ Alastair Lamb, Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846-1990, Roxford Books 1991, ISBN 0-907129-06-4

- ^ Sword For Pen, TIME Magazine, April 12, 1937

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. "Sikkim."

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. "Nepal.", Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. "Bhutan."

- ^ Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 221–222

- ^ Nasim Yousaf: Hidden Facts Behind British India’s Freedom: A Scholarly Look into Allama Mashraqi and Quaid-e-Azam’s Political Conflict

- ^ V.D.Savarkar, Samagra Savarkar Wangmaya Hindu Rasthra Darshan (Collected works of V.D.Savarkar) Vol VI, Maharashtra Prantik Hindusabha, Poona, 1963, p 296

- ^ Jalal, Ayesha Jalal (1985). The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, The Muslim League and the Demand Pakistan. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Thomas RGC, Nations, States, and Secession: Lessons from the Former Yugoslavia, Mediterranean Quarterly, Volume 5 Number 4 Fall 1994, pp. 40–65, Duke University Press

- ^ a b c d (Spate 1947, pp. 126-137)

- ^ Death toll in the partition

- ^ Markovits, Claude (2000). The Global World of Indian Merchants, 1750-1947. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278. ISBN 0521622859.

- ^ K. Z. Islam, 2002, The Punjab Boundary Award, Inretrospect

- ^ Partitioning India over lunch, Memoirs of a British civil servant Christopher Beaumont

- ^ Stanley Wolpert, 2006, Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515198-4

- ^ Richard Symonds, 1950, The Making of Pakistan, London, ASIN B0000CHMB1, p 74

- ^ "Once in office, Mountbatten quickly became aware if Britain were to avoid involvement in a civil war, which seemed increasingly likely, there was no alternative to partition and a hasty exit from India" Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World, p 72

- ^ Lawrence J. Butler, 2002, Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World, p 72

- ^ Ronald Hyam, Britain's Declining Empire: The Road to Decolonisation, 1918-1968, page 113; Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521866499, 2007

- ^ Lawrence James, Rise and Fall of the British Empire

- ^ Kaur, Ravinder (2007). Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195683776.

Further reading

Popularizations

- Collins, Larry and Dominique Lapierre: Freedom at Midnight. London: Collins, 1975. ISBN 0-00-638851-5

- Zubrzycki, John. (2006) The Last Nizam: An Indian Prince in the Australian Outback. Pan Macmillan, Australia. ISBN 978-0-3304-2321-2.

Memoir

- Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam: India Wins Freedom, Orient Longman, 1988. ISBN 81-250-0514-5

Academic textbooks and monographs

- Ansari, Sarah. 2005. Life after Partition: Migration, Community and Strife in Sindh: 1947—1962. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. 256 pages. ISBN 019597834X.

- Butalia, Urvashi. 1998. The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 308 pages. ISBN 0822324946

- Chatterji, Joya. 2002. Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition, 1932—1947. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 323 pages. ISBN 0521523281.

- Gilmartin, David. 1988. Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. Berkeley: University of California Press. 258 pages. ISBN 0520062493.

- Gossman, Partricia. 1999. Riots and Victims: Violence and the Construction of Communal Identity Among Bengali Muslims, 1905-1947. Westview Press. 224 pages. ISBN 0813336252

- Hansen, Anders Bjørn. 2004. "Partition and Genocide: Manifestation of Violence in Punjab 1937-1947", India Research Press. ISBN 9788187943259.

- Hasan, Mushirul (2001), India's Partition: Process, Strategy and Mobilization, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 444 pages, ISBN 0195635043.

- Ikram, S. M. 1995. Indian Muslims and Partition of India. Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 8171563740

- Jain, Jasbir (2007), Reading Partition, Living Partition, Rawat Publications, 338 pages, ISBN 8131600459

- Jalal, Ayesha (1993), The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 334 pages, ISBN 0521458501

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2007. "Since 1947: Partition Narratives among Punjabi Migrants of Delhi". Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195683776.

- Khan, Yasmin (2007), The Great Partition: The Making of India and Pakistan, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 250 pages, ISBN 0300120788

- Lamb, Alastair (1991), Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846-1990, Roxford Books, ISBN 0-907129-06-4

- Metcalf, Barbara & Thomas R. Metcalf (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (Cambridge Concise Histories), Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Pp. xxxiii, 372, ISBN 0521682258.

- Page, David, Anita Inder Singh, Penderel Moon, G. D. Khosla, and Mushirul Hasan. 2001. The Partition Omnibus: Prelude to Partition/the Origins of the Partition of India 1936-1947/Divide and Quit/Stern Reckoning. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195658507

- Pandey, Gyanendra. 2002. Remembering Partition:: Violence, Nationalism and History in India. Cambride, UK: Cambridge University Press. 232 pages. ISBN 0521002508

- Raza, Hashim S. 1989. Mountbatten and the partition of India. New Delhi: Atlantic. ISBN 81-7156-059-8

- Shaikh, Farzana. 1989. Community and Consensus in Islam: Muslim Representation in Colonial India, 1860—1947. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 272 pages. ISBN 0521363284.

- Talbot, Ian and Gurharpal Singh (eds). 1999. Region and Partition: Bengal, Punjab and the Partition of the Subcontinent. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 420 pages. ISBN 0195790510.

- Talbot, Ian. 2002. Khizr Tiwana: The Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 216 pages. ISBN 0195795512.

- Talbot, Ian. 2006. Divided Cities: Partition and Its Aftermath in Lahore and Amritsar. Oxford and Karachi: Oxford University Press. 350 pages. ISBN 0195472268.

- Wolpert, Stanley. 2006. Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. 272 pages. ISBN 0195151984.

- J. Butler, Lawrence. 2002. Britain and Empire: Adjusting to a Post-Imperial World. London: I.B.Tauris. 256 pages. ISBN 186064449X

- Khosla, G. D. Stern reckoning : a survey of the events leading up to and following the partition of India New Delhi: Oxford University Press:358 pages Published: February 1990 ISBN 0195624173

Articles

- Review by Chudhry Manzoor Ahmed Marxist MP in Pakistani Parliament book by Lal Khan 'Partition can it be undone?'

- Gilmartin, David. 1998. "Partition, Pakistan, and South Asian History: In Search of a Narrative." The Journal of Asian Studies, 57(4):1068-1095.

- Jeffrey, Robin. 1974. "The Punjab Boundary Force and the Problem of Order, August 1947" - Modern Asian Studies 8(4):491-520.

- Kaur Ravinder. 2007. "India and Pakistan: Partition Lessons". Open Democracy.

- Kaur, Ravinder. 2006. "The Last Journey: Social Class in the Partition of India". Economic and Political Weekly, June 2006. www.epw.org.in

- Mookerjea-Leonard, Debali. 2005. "Divided Homelands, Hostile Homes: Partition, Women and Homelessness". Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 40(2):141-154.

- Morris-Jones. 1983. "Thirty-Six Years Later: The Mixed Legacies of Mountbatten's Transfer of Power". International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs), 59(4):621-628.

- Spate, O. H. K. (1947), "The Partition of the Punjab and of Bengal", The Geographical Journal 110 (4/6): 201-218

- Spear, Percival. 1958. "Britain's Transfer of Power in India." Pacific Affairs, 31(2):173-180.

- Talbot, Ian. 1994. "Planning for Pakistan: The Planning Committee of the All-India Muslim League, 1943-46". Modern Asian Studies, 28(4):875-889.

- Visaria, Pravin M. 1969. "Migration Between India and Pakistan, 1951-61" Demography, 6(3):323-334.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Partition of British India |

Bibliographies

- Select Research Bibliography on the Partition of India, Compiled by Vinay Lal, Department of History, UCLA; University of California at Los Angeles list

- A select list of Indian Publications on the Partition of India (Punjab & Bengal); University of Virginia list

- South Asian History: Colonial India — University of California, Berkeley Collection of documents on colonial India, Independence, and Partition

- Indian Nationalism — Fordham University archive of relevant public-domain documents

Other links

- Can Partition be undone? Economic and Political Review India by Ranabir Sammadar

- Partition of India by A. G. Noorani.

- Clip from 1947 newsreel showing Indian independence ceremony

- Partition of Bengal, 1947, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Personal Stories of Hindu Sindhis

- Through My Eyes Website Imperial War Museum - Online Exhibition (including images, video and interviews with refugees from the Partition of India)