Moment (mathematics)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The concept of moment in mathematics evolved from the concept of moment in physics. The nth moment of a real-valued function f(x) of a real variable about a value c is

It is possible to define moments for random variables in a more general fashion than moments for real values. See Moments in metric spaces.

The moments about zero[clarification needed] are usually referred to simply as the moments of a function. Usually, except in the special context of the problem of moments, the function will be a probability density function. The nth moment (about zero) of a probability density function f(x) is the expected value of Xn. The moments about its mean μ are called central moments; these describe the shape of the function, independently of translation.

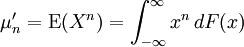

If f is a probability density function, then the value integral above is called the nth moment of the probability distribution. More generally, if F is a cumulative probability distribution function of any probability distribution, which may not have a density function, then the nth moment of the probability distribution is given by the Riemann-Stieltjes integral

where X is a random variable that has this distribution and E the expectation operator.

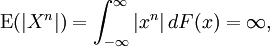

When

then the moment is said not to exist. If the nth moment about any point exists, so does (n − 1)th moment, and all lower-order moments, about every point.

Contents |

[edit] Significance of the moments

The first moment about zero, if it exists, is the expectation of X, i.e. the mean of the probability distribution of X, designated μ. In higher orders, the central moments are more interesting than the moments about zero.

The nth central moment of the probability distribution of a random variable X is

The first central moment is thus 0.

[edit] Variance

The second central moment is the variance, the positive square root of which is the standard deviation, σ.

[edit] Normalized moments

The normalized nth central moment or standardized moment is the nth central moment divided by σn; the normalized nth central moment of x = E((x − μ)n)/σn. These normalized central moments are dimensionless quantities, which represent the distribution independently of any linear change of scale.

[edit] Skewness

The third central moment is a measure of the lopsidedness of the distribution; any symmetric distribution will have a third central moment, if defined, of zero. The normalized third central moment is called the skewness, often γ. A distribution that is skewed to the left (the tail of the distribution is heavier on the right) will have a negative skewness. A distribution that is skewed to the right (the tail of the distribution is heavier on the left), will have a positive skewness.

For distributions that are not too different from the normal distribution, the median will be somewhere near μ − γσ/6; the mode about μ − γσ/2.[citation needed]

[edit] Kurtosis

The fourth central moment is a measure of whether the distribution is tall and skinny or short and squat, compared to the normal distribution of the same variance. Since it is the expectation of a fourth power, the fourth central moment, where defined, is always positive; and except for a point distribution, it is always strictly positive. The fourth central moment of a normal distribution is 3σ4.

The kurtosis κ is defined to be the normalized fourth central moment minus 3. (Equivalently, as in the next section, it is the fourth cumulant divided by the square of the variance.) Some authorities do not subtract three, but it is usually more convenient to have the normal distribution at the origin of coordinates. If a distribution has a peak at the mean and long tails, the fourth moment will be high and the kurtosis positive; and conversely; thus, bounded distributions tend to have low kurtosis.

The kurtosis can be positive without limit, but κ must be greater than or equal to γ2 − 2; equality only holds for binary distributions. For unbounded skew distributions not too far from normal, κ tends to be somewhere in the area of γ2 and 2γ2.

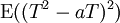

The inequality can be proven by considering

where T = (X − μ)/σ. This is the expectation of a square, so it is non-negative whatever a is; on the other hand, it's also a quadratic equation in a. Its discriminant must be non-positive, which gives the required relationship.

[edit] Cumulants

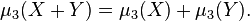

The first moment and the second and third unnormalized central moments are linear in the sense that if X and Y are independent random variables then

and

and

(These can also hold for variables that satisfy weaker conditions than independence. The first always holds; if the second holds, the variables are called uncorrelated).

In fact, these are the first three cumulants and all cumulants share this linearity property.

[edit] Sample moments

The moments of a population can be estimated using the sample k-th moment

applied to a sample X1,X2,..., Xn drawn from the population.

It can be trivially shown that the expected value of the sample moment is equal to the k-th moment of the population, if that moment exists, for any sample size n. It is thus an unbiased estimator.

[edit] Problem of moments

The problem of moments seeks characterizations of sequences { μ′n : n = 1, 2, 3, ... } that are sequences of moments of some function f.

[edit] Partial moments

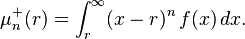

Partial moments are sometimes referred to as "one-sided moments." The nth order lower and upper partial moments with respect to a reference point r may be expressed as

Partial moments are normalized by being raised to the power 1/n. The upside potential ratio may be expressed as a ratio of a first-order upper partial moment to a normalized second-order lower partial moment.

[edit] Moments in metric spaces

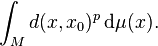

Let (M, d) be a metric space, and let B(M) be the Borel σ-algebra on M, the σ-algebra generated by the d-open subsets of M. (For technical reasons, it is also convenient to assume that M is a separable space with respect to the metric d.) Let 1 ≤ p ≤ +∞.

The pth moment of a measure μ on the measurable space (M, B(M)) about a given point x0 in M is defined to be

μ is said to have finite pth moment if the pth moment of μ about x0 is finite for some x0 ∈ M.

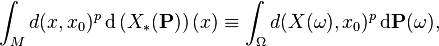

This terminology for measures carries over to random variables in the usual way: if (Ω, Σ, P) is a probability space and X : Ω → M is a random variable, then the pth moment of X about x0 ∈ M is defined to be

and X has finite pth moment if the pth moment of X about x0 is finite for some x0 ∈ M.

[edit] See also

- Hamburger moment problem

- Hausdorff moment problem

- Image moments

- Method of moments

- Second moment method

- Standardized moment

- Stieltjes moment problem

- Taylor expansions for the moments of functions of random variables

[edit] External links

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||