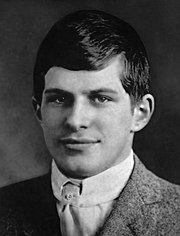

William James Sidis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

William James Sidis (April 1, 1898 – July 17, 1944) was an American child prodigy with exceptional mathematical and linguistic abilities. He first became famous for his precocity, and later for his eccentricity and withdrawal from the public eye. He avoided mathematics entirely in later life, writing on other subjects under a number of pseudonyms. With an estimated ratio IQ of 250-300[1], he is often cited in informal contexts as one of the most intelligent people who ever lived.

Contents |

[edit] Biography

[edit] Parents and upbringing (1898–1909)

William James Sidis was born to Russian-Jewish immigrants on April 1, 1898 in New York City. His father, Boris Sidis, Ph.D., M.D., had emigrated in 1887 to escape political persecution. His mother, Sarah Mandelbaum Sidis, M.D., and her family had fled the pogroms about 1889. Sarah attended Boston University and graduated from its School of Medicine in 1897.[2] William was named after his godfather, Boris's friend and colleague, the American philosopherWilliam James. Boris earned his degrees at Harvard University, and taught psychology there. He was a psychiatrist, and published numerous books and articles, performing pioneering work in abnormal psychology. Boris was a polyglot and his son William would become one too at a young age.

Instead of the more common disciplinary approach to parenting, Sidis's parents believed in nurturing a precocious and fearless love of knowledge, for which they were criticized. Nevertheless, the young Sidis could read the New York Times at 18 months,[3] reportedly taught himself eight languages (Latin, Greek, French, Russian, German, Hebrew, Turkish, and Armenian) by age eight, and invented another, which he called Vendergood.

[edit] Harvard and college life (1909–1915)

Although the University had previously refused to let his father enroll him at age nine because he was still a child, Sidis set a record in 1909 by becoming the youngest person to enroll at Harvard College. He was 11 years old, and entered Harvard as part of a program to enroll gifted students early. The experimental group included mathematician Norbert Wiener, Richard Buckminster Fuller, and composer Roger Sessions. In early 1910, his mastery of higher mathematics was such that he lectured the Harvard Mathematical Club on four-dimensional bodies,[4] prompting MIT professor Daniel F. Comstock to predict that Sidis would become a great mathematician and a leader in that science in the future.[5] Sidis began taking a full-time course load in 1910 and earned his Bachelor of Arts degree, cum laude, on June 18, 1914, at age 16.[6]

Shortly after graduation, he told reporters that he wanted to live the perfect life, which to him meant living in seclusion. He granted an interview to a reporter from the Boston Herald, which published his vows to remain celibate and never to marry, and a statement that women did not appeal to him (however, he later developed a strong affection for a young woman named Martha Foley[5]). He later enrolled at Harvard's Graduate School of Arts and Sciences.

[edit] Teaching and further education (1915-1919)

After a group of Harvard students threatened physical harm, his parents secured him a job at the William Marsh Rice Institute for the Advancement of Letters, Science, and Art (now Rice University) in Houston, Texas as a mathematics teaching assistant. He arrived at Rice in December 1915 at the age of 17. He was a Graduate Fellow working toward his doctorate.

Sidis taught three classes: Euclidean geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, and trigonometry (he wrote a textbook for the Euclidean geometry course in Greek). After less than a year, frustrated with the department, his teaching requirements, and his treatment by students older than him, Sidis left his post and returned to New England. When a friend later asked him why he had left, he replied, "I never knew why they gave me the job in the first place — I'm not much of a teacher. I didn't leave — I was asked to go." Sidis abandoned his pursuit of a graduate degree in mathematics and enrolled at the Harvard Law School in September 1916, but withdrew in good standing in his final year in March 1919.[7]

[edit] Politics and arrest (1919–1921)

In 1919, shortly after his withdrawal from law school, Sidis was arrested for participating in a socialist May Day parade in Boston that turned into a scuffle. He was sentenced to 18 months in prison under the Sedition Act of 1918 for rioting and assault. Sidis's arrest featured prominently in newspapers, as his early graduation from Harvard had garnered considerable local celebrity. During the trial, Sidis stated that he had been a conscientious objector of the World War I draft, did not believe in a god, and that he was a socialist[8] (though he later developed his own philosophy of quasi-"libertarianism" based on individual rights and "the American social continuity").[9][10] His father made an arrangement with the district attorney to keep him out of prison before his appeal came to trial; his parents, instead, held him in their sanitorium in New Hampshire for a year, then took him to California where he spent another year.[11] While at the sanitorium, his parents set about "reforming" him and threatened him with transfer to an insane asylum.[5][11]

[edit] Later life (1921–1944)

After escaping back to the East Coast in 1921, Sidis was determined to live an independent and private life, and would only take work running adding machines or other fairly menial tasks. He worked in New York City and became estranged from his parents. It took a number of years before he was cleared to return to Massachusetts, and he remained concerned about possible arrest for years.[5] He devoted himself to his hobby of collecting streetcar transfers, published periodicals, and taught small circles of interested friends his version of American history.

In 1944, Sidis won a settlement from The New Yorker for publishing an article about him in 1937, which he alleged contained many false statements.[12] Under the title "Where Are They Now?", the pseudonymous article described Sidis's life as lonely, in a "hall bedroom in Boston's shabby South End".[13] Lower courts had dismissed Sidis as a public figure with no right to challenge personal publicity. He lost an appeal of an invasion of privacy lawsuit at the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1940 over the same article. Judge Charles Edward Clark expressed sympathy for Sidis — who claimed that the publication had exposed him to "public scorn, ridicule, and contempt" and caused him "grievous mental anguish [and] humiliation" — but found that the court was not disposed to "afford to all the intimate details of private life an absolute immunity from the prying of the press".[13]

Sidis died in 1944 of a cerebral hemorrhage in Boston at the age of 46.[14] His father had died of the same malady in 1923 at age 56.

[edit] Remembrances

Abraham Sperling, director of New York City's Aptitude Testing Institute, said after Sidis' death that according to his calculations, Sidis "easily had an IQ between 250 and 300" and that there was no evidence that his intellect had declined in adulthood.[15][5] (His father once dismissed tests of intelligence as "silly, pedantic, absurd, and grossly misleading".[16]) Sperling commented:

"What the journalists did not report, and perhaps did not know, was that during all the years of his obscure employments he was writing original treatises on history, government, economics and political affairs. In a visit to his mother's home I was permitted to see the contents of a trunkful of original manuscript material that Bill Sidis composed."[17]

From writings on astrophysics, to Native American studies, to a comprehensive and definitive taxonomy of vehicle transfers, an equally comprehensive study of civil engineering and vehicles, and several well-substantiated lost texts on anthropology, philology, and transportation systems, Sidis covered a broad range of subjects.

[edit] Publications and subjects of research

Aside from mathematics, subjects on which Sidis wrote or lectured included cosmology, psychology, and Native American history. Some of his ideas concerned cosmological reversibility,[18]"social continuity," [19] and individual rights in the United States.[10]

In The Animate and the Inanimate (1925), Sidis predicted the existence of regions of space where the second law of thermodynamics operated in reverse to the temporal direction that we experience in our local area. Everything outside of what we would today call a galaxy would be such a region. Sidis claimed that the matter in this region would not generate light. (These dark areas of the universe are not properly dark matter or black holes as they are used in contemporary cosmology.) This work on cosmology, based on his theory of reversibility of the second law of thermodynamics was the only book published under his name.[18]

Sidis' The Tribes and the States (ca. 1935) employs the pseudonym "John W. Shattuck," giving a 100,000-year history of North America's inhabitants, from prehistoric times to 1828.[20] In this text, he suggests that "there were red men at one time in Europe as well as in America."[21]

Sidis was also a "peridromophile," a term he coined for people fascinated with transportation research and streetcar systems. He wrote a treatise on streetcar transfers under the pseudonym of "Frank Folupa" that identified means of increasing public transport usage.[22]

In 1930, Sidis was awarded a patent for a rotary perpetual calendar that took into account leap years.[23] Also, in his adult years, it was estimated that he could speak more than forty languages, and learn a new language in a day.[24]

[edit] Sidis in educational discussions

The debate about Sidis' manner of upbringing occurred within a larger discourse about the best way to educate children. Newspapers criticized the child-rearing methods of Boris Sidis. Most educators of the day believed that schools should expose children to common experiences to create good citizens, and most psychologists thought that intelligence was hereditary — a position that precluded early childhood education at home.[25]

The difficulties that Sidis and other highly gifted young students encountered in dealing with the social structure of a university setting helped shape opinion against allowing them to rapidly advance through higher education. The debate over gifted education continues today, and Sidis remains a topic of discussion. Cast in modern standards, scholars usually classify Sidis as a profoundly gifted individual, and some critics use Sidis as the most vivid example of how gifted youth do not always achieve corresponding success as adults — in either material or creative terms.

Many of these depictions rely on Sidis' negative portrayal in the press of the day, which refused to acknowledge that his intellect could be attributed to anything but monotonous cramming — precisely what his parents had argued against. In fact, his mother later noted that newspaper accounts of her son bore little resemblance to William himself.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Lyons, Viktoria; Fitzgerald, Michael (2005), Asperger Syndrome: A Gift Or A Curse, Nova Publishers, ISBN 1594543879, Chapter VII.

- ^ HISTORY OF HOMOEOPATHY AND ITS INSTITUTIONS IN AMERICA By William Harvey King, M. D., LL. D. Presented by Sylvain Cazalet

- ^ Wallace, p. 23.

- ^ "Wonderful Boys of History Compared With Sidis; All Except Macaulay Showed Special Ability in Mathematics -- Instances of Boys Having 'Universal Genius'". New York Times. 1910-01-16. p. SM11.

- ^ a b c d e The Prodigy

- ^ http://www.sidis.net/transcript1.jpg

- ^ Harvard Transcripts

- ^ Sidis Gets Year and Half in Jail, Boston Herald, May 14, 1919

- ^ Sidis, William James (June 1938), ""Libertarian"", Continuity News (Cambridge, Mass.) (2): 4, http://sidis.net/continuitynews2.htm.

- ^ a b Sidis, William James, The Concept of Rights, American Independence Society, http://www.sidis.net/rights2.htm

- ^ a b Railroading in the Past

- ^ Sidis vs New Yorker

- ^ a b LaMay, p. 63.

- ^ Shirley Smith's Letter to the Editor

- ^ Wallace, p. 283.

- ^ Foundations of Normal and Abnormal psychology

- ^ Sperling, Abraham (1946). Psychology for the Millions.

- ^ a b Sidis, William James (1925), The Animate and the Inanimate, Boston, Mass.: The Gorham Press, http://www.sidis.net/ANIMContents.htm,

- ^ Sidis, William James, Continuity News, http://www.sidis.net/continuitynewsmenu.htm

- ^ The Tribes and the States,Table of Contents

- ^ The Tribes and the States, Native American history

- ^ Notes on the Collection of Transfers

- ^ Perpetual Calendar

- ^ Wallace, p. 284.

- ^ Kett, Joseph F. (1978). "Curing the Disease of Precocity". The American Journal of Sociology 84 (suppl.): S183–S211.

[edit] References

- LaMay, Craig L. (2003). Journalism and the Debate Over Privacy. LEA's Communication Series. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.. ISBN 9780805846263.

- Wallace, Amy (1986). The prodigy: a biography of William James Sidis, America's greatest child prodigy. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.. ISBN 0-525-24404-2.

- A review of "The Prodigy" by Martha Brassil

- Book review by Robert N. Seitz, Ph.D.

[edit] External links

- "Sidis Archives" website

- Details and outline of his life

- The Rise and Fall of William J. Sidis - a brief biography

- The Newsletter of the Rice (University) Historical Society

- "Apologia Pro Sua Vita", 1924 article from Harvard newspaper

- Family Biographies by Sarah Sidis

- 'A Story of Genius'

- William James Sidis & Peridromophilia

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Sidis, William James |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | American prodigy |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 1, 1898 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 17, 1944 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Boston, Massachusetts |