Merge sort

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Example of merge sort sorting a list of random dots. | |

| Class | Sorting algorithm |

|---|---|

| Data structure | Array |

| Worst case performance | Θ(nlogn) |

| Best case performance | Θ(nlogn) |

| Average case performance | Θ(nlogn) |

| Worst case space complexity | Θ(n) |

| Optimal | Sometimes |

Merge sort is an O(n log n) comparison-based sorting algorithm. In most implementations it is stable, meaning that it preserves the input order of equal elements in the sorted output. It is an example of the divide and conquer algorithmic paradigm. It was invented by John von Neumann in 1945.

Contents |

[edit] Algorithm

Conceptually, a merge sort works as follows:

- If the list is of length 0 or 1, then it is already sorted. Otherwise:

- Divide the unsorted list into two sublists of about half the size.

- Sort each sublist recursively by re-applying merge sort.

- Merge the two sublists back into one sorted list.

Merge sort incorporates two main ideas to improve its runtime:

- A small list will take fewer steps to sort than a large list.

- Fewer steps are required to construct a sorted list from two sorted lists than two unsorted lists. For example, you only have to traverse each list once if they're already sorted (see the merge function below for an example implementation).

Example: Using merge sort to sort a list of integers contained in an array:

Suppose we have an array A with n indices ranging from A0 to An − 1. We apply merge sort to A(A0..Ac − 1) and A(Ac..An − 1) where c is the integer part of n / 2. When the two halves are returned they will have been sorted. They can now be merged together to form a sorted array.

In a simple pseudocode form, the algorithm could look something like this:

function merge_sort(m)

var list left, right, result

if length(m) ≤ 1

return m

// This calculation is for 1-based arrays. For 0-based, use length(m)/2 - 1.

var middle = length(m) / 2

for each x in m up to middle

add x to left

for each x in m after middle

add x to right

left = merge_sort(left)

right = merge_sort(right)

result = merge(left, right)

return result

There are several variants for the merge() function, the simplest variant could look like this:

function merge(left,right)

var list result

while length(left) > 0 and length(right) > 0

if first(left) ≤ first(right)

append first(left) to result

left = rest(left)

else

append first(right) to result

right = rest(right)

end while

while length(left) > 0

append left to result

while length(right) > 0

append right to result

return result

[edit] Analysis

In sorting n items, merge sort has an average and worst-case performance of O(n log n). If the running time of merge sort for a list of length n is T(n), then the recurrence T(n) = 2T(n/2) + n follows from the definition of the algorithm (apply the algorithm to two lists of half the size of the original list, and add the n steps taken to merge the resulting two lists). The closed form follows from the master theorem.

In the worst case, merge sort does approximately (n ⌈lg n⌉ - 2⌈lg n⌉ + 1) comparisons, which is between (n lg n - n + 1) and (n lg n + n + O(lg n)). [1]

For large n and a randomly ordered input list, merge sort's expected (average) number of comparisons approaches α·n fewer than the worst case where

In the worst case, merge sort does about 39% fewer comparisons than quicksort does in the average case; merge sort always makes fewer comparisons than quicksort, except in extremely rare cases, when they tie, where merge sort's worst case is found simultaneously with quicksort's best case. In terms of moves, merge sort's worst case complexity is O(n log n)—the same complexity as quicksort's best case, and merge sort's best case takes about half as many iterations as the worst case.[citation needed]

Recursive implementations of merge sort make 2n - 1 method calls in the worst case, compared to quicksort's n, thus has roughly twice as much recursive overhead as quicksort. However, iterative, non-recursive, implementations of merge sort, avoiding method call overhead, are not difficult to code. Merge sort's most common implementation does not sort in place; therefore, the memory size of the input must be allocated for the sorted output to be stored in.

Sorting in-place is possible but is very complicated, and will offer little performance gains in practice, even if the algorithm runs in O(n log n) time.[2] In these cases, algorithms like heapsort usually offer comparable speed, and are far less complex. Additionally, unlike the standard merge sort, in-place merge sort is not a stable sort.

Merge sort is more efficient than quicksort for some types of lists if the data to be sorted can only be efficiently accessed sequentially, and is thus popular in languages such as Lisp, where sequentially accessed data structures are very common. Unlike some (efficient) implementations of quicksort, merge sort is a stable sort as long as the merge operation is implemented properly.

As can be seen from the procedure merge sort, there are some complaints. One complaint we might raise is its use of 2n locations; the additional n locations were needed because one couldn't reasonably merge two sorted sets in place. But despite the use of this space the algorithm must still work hard, copying the result placed into Result list back into m list on each call of merge . An alternative to this copying is to associate a new field of information with each key (the elements in m are called keys). This field will be used to link the keys and any associated information together in a sorted list (a key and its related information is called a record). Then the merging of the sorted lists proceeds by changing the link values; no records need to be moved at all. A field which contains only a link will generally be smaller than an entire record so less space will also be used.

[edit] Merge sorting tape drives

Merge sort is so inherently sequential that it's practical to run it using slow tape drives as input and output devices. It requires very little memory, and the memory required does not change with the number of data elements.

For the same reason it is also useful for sorting data on disk that is too large to fit entirely into primary memory. On tape drives that can run both backwards and forwards, merge passes can be run in both directions, avoiding rewind time.

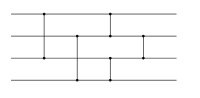

If you have four tape drives, it works as follows:

- Divide the data to be sorted in half and put half on each of two tapes

- Merge individual pairs of records from the two tapes; write two-record chunks alternately to each of the two output tapes

- Merge the two-record chunks from the two output tapes into four-record chunks; write these alternately to the original two input tapes

- Merge the four-record chunks into eight-record chunks; write these alternately to the original two output tapes

- Repeat until you have one chunk containing all the data, sorted --- that is, for log n passes, where n is the number of records.

For almost-sorted data on tape, a bottom-up "natural merge sort" variant of this algorithm is popular.

The bottom-up "natural merge sort" merges whatever "chunks" of in-order records are already in the data. In the worst case (reversed data), "natural merge sort" performs the same as the above -- it merges individual records into 2-record chunks, then 2-record chunks into 4-record chunks, etc. In the best case (already mostly-sorted data), "natural merge sort" merges large already-sorted chunks into even larger chunks, hopefully finishing in fewer than log n passes.

In a simple pseudocode form, the "natural merge sort" algorithm could look something like this:

# Original data is on the input tape; the other tapes are blank

function merge_sort(input_tape, output_tape, scratch_tape_C, scratch_tape_D)

while any records remain on the input_tape

while any records remain on the input_tape

merge( input_tape, output_tape, scratch_tape_C)

merge( input_tape, output_tape, scratch_tape_D)

while any records remain on C or D

merge( scratch_tape_C, scratch_tape_D, output_tape)

merge( scratch_tape_C, scratch_tape_D, input_tape)

# take the next sorted chunk from the input tapes, and merge into the single given output_tape.

# tapes are scanned linearly.

# tape[next] gives the record currently under the read head of that tape.

# tape[current] gives the record previously under the read head of that tape.

# (Generally both tape[current] and tape[previous] are buffered in RAM ...)

function merge(left[], right[], output_tape[])

do

if left[current] ≤ right[current]

append left[current] to output_tape

read next record from left tape

else

append right[current] to output_tape

read next record from right tape

while left[current] < left[next] and right[current] < right[next]

if left[current] < left[next]

append current_left_record to output_tape

if right[current] < right[next]

append current_right_record to output_tape

return

Either form of merge sort can be generalized to any number of tapes.

[edit] Optimizing merge sort

On modern computers, locality of reference can be of paramount importance in software optimization, because multi-level memory hierarchies are used. Cache-aware versions of the merge sort algorithm, whose operations have been specifically chosen to minimize the movement of pages in and out of a machine's memory cache, have been proposed. For example, the tiled merge sort algorithm stops partitioning subarrays when subarrays of size S are reached, where S is the number of data items fitting into a single page in memory. Each of these subarrays is sorted with an in-place sorting algorithm, to discourage memory swaps, and normal merge sort is then completed in the standard recursive fashion. This algorithm has demonstrated better performance on machines that benefit from cache optimization. [3]

M. A. Kronrod suggested in 1969 an alternative version of merge sort that used constant additional space [4]. This algorithm was refined by Katajainen, Pasanen and Teuhola [5].

[edit] Comparison with other sort algorithms

Although heapsort has the same time bounds as merge sort, it requires only Θ(1) auxiliary space instead of merge sort's Θ(n), and is often faster in practical implementations. Quicksort, however, is considered by many to be the fastest general-purpose sort algorithm. On the plus side, merge sort is a stable sort, parallelizes better, and is more efficient at handling slow-to-access sequential media. Merge sort is often the best choice for sorting a linked list: in this situation it is relatively easy to implement a merge sort in such a way that it requires only Θ(1) extra space, and the slow random-access performance of a linked list makes some other algorithms (such as quicksort) perform poorly, and others (such as heapsort) completely impossible.

As of Perl 5.8, merge sort is its default sorting algorithm (it was quicksort in previous versions of Perl). In Java, the Arrays.sort() methods use merge sort or a tuned quicksort depending on the datatypes[1] and for implementation efficiency switch to insertion sort when fewer than seven array elements are being sorted.[2]

[edit] Utility in online sorting

Merge sort's merge operation is useful in online sorting, where the list to be sorted is received a piece at a time, instead of all at the beginning (see online algorithm). In this application, we sort each new piece that is received using any sorting algorithm, and then merge it into our sorted list so far using the merge operation. However, this approach can be expensive in time and space if the received pieces are small compared to the sorted list — a better approach in this case is to store the list in a self-balancing binary search tree and add elements to it as they are received.

[edit] References

[edit] Citations and notes

- ^ The worst case number given here does not agree with that given in Knuth's Art of Computer Programming, Vol 3. The discrepancy is due to Knuth analyzing a variant implementation of merge sort that is slightly sub-optimal

- ^ Jyrki Katajainen. Practical In-Place Mergesort. Nordic Journal of Computing. 1996.

- ^ A. LaMarca and R. E. Ladner, ``The influence of caches on the performance of sorting," Proc. 8th Ann. ACM-SIAM Symp. on Discrete Algorithms (SODA97), 1997, 370-379.

- ^ Kronrod, M. A. (1969), "Optimal ordering algorithm without operational field", Soviet Mathematics - Doklady 10: 744

- ^ Katajainen, Jyrki; Pasanen, Tomi; Teuhola, Jukka (1996), "Practical in-place mergesort", Nordic Journal of Computing 3: 27-40, http://www.diku.dk/hjemmesider/ansatte/jyrki/Paper/mergesort_NJC.ps, retrieved on 2009-04-04

[edit] General

- Knuth, Donald (1998). "Section 5.2.4: Sorting by Merging". The Art of Computer Programming. Addison-Wesley. pp. 158–168. ISBN 0-201-89685-0.

- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E., Rivest, Ronald L., Stein, Clifford (2001) [1990]. "2.3: Designing algorithms". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. pp. pp. 27–37. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- Sun Microsystems, Inc.. "Arrays API". http://java.sun.com/javase/6/docs/api/java/util/Arrays.html. Retrieved on 2007-11-19.

- Sun Microsystems, Inc.. "java.util.Arrays.java". https://openjdk.dev.java.net/source/browse/openjdk/jdk/trunk/jdk/src/share/classes/java/util/Arrays.java?view=markup. Retrieved on 2007-11-19.

[edit] External links

| The Wikibook Algorithm implementation has a page on the topic of |

- Animated Sorting Algorithms: Merge Sort – graphical demonstration and discussion of array-based merge sort

- Analyze Merge Sort in an online Javascript IDE

- Merge sort applet with level order recursive calls to help improve algorithm analysis

- Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures: Merge sort

- Literate implementations of merge sort in various languages on LiteratePrograms

- Implementation for C++

- A colored graphical Java applet which allows experimentation with initial state and shows statistics

- Simon Tatham's explanation and code for a merge sort

- MergeSort tutorial and Java code for beginners

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||