Riemann zeta function

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In mathematics, the Riemann zeta function, named after German mathematician Bernhard Riemann, is a prominent function of great significance in number theory because of its relation to the distribution of prime numbers. It also has applications in other areas such as physics, probability theory, and applied statistics.

The Riemann hypothesis, a conjecture about the distribution of the zeros of the Riemann zeta function, is considered by many mathematicians to be the most important unsolved problem in pure mathematics.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Definition

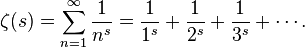

The Riemann zeta-function  is the function of a complex variable

is the function of a complex variable  initially defined by the following infinite series:

initially defined by the following infinite series:

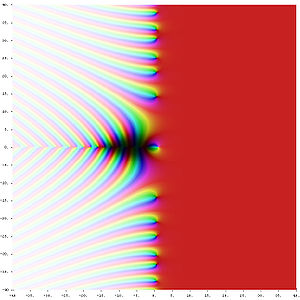

This is a Dirichlet series which converges absolutely to an analytic function on the open half-plane of s such that Re(s) > 1 and diverges elsewhere. The function defined by the series on the half-plane of convergence can be continued analytically to all complex s ≠ 1. For s = 1 the series is the harmonic series which diverges to infinity. As a result, the zeta function is a meromorphic function of the complex variable s, which is holomorphic everywhere except for a simple pole at s = 1 with residue 1.

[edit] Specific values

For any positive even number 2n,

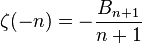

where B2n is a Bernoulli number, while for negative integers, one has

for  ,

,

so in particular ζ vanishes at the negative even integers: No such simple expression is known for odd positive integers.

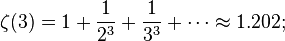

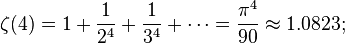

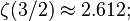

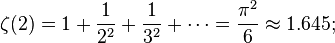

The values of the zeta function obtained from integral arguments are called zeta constants. The following are the most commonly used values of the Riemann zeta function.

- this is the harmonic series.

- this is employed in calculating the critical temperature for a Bose–Einstein condensate in physics, and for spin-wave physics in magnetic systems.

- the demonstration of this equality is known as the Basel problem. The reciprocal of this sum answers the question: What is the probability that two numbers selected at random are relatively prime?[2]

-

- this is called Apéry's constant.

-

- Stefan–Boltzmann law and Wien approximation in physics.

[edit] Euler product formula

The connection between the zeta function and prime numbers was discovered by Leonhard Euler, who proved the identity

where, by definition, the left hand side is ζ(s) and the infinite product on the right hand side extends over all prime numbers p (such expressions are called Euler products):

Both sides of the Euler product formula converge for Re(s) > 1. The proof of Euler's identity uses only the formula for the geometric series and the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. Since the harmonic series, obtained when s = 1, diverges, Euler's formula implies that there are infinitely many primes.

For s an integer number, the Euler product formula can be used to calculate the probability that s randomly selected integers are relatively prime. It turns out that this probability is indeed 1/ζ(s).

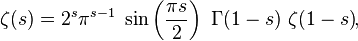

[edit] The functional equation

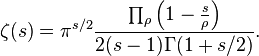

The Riemann zeta function satisfies the functional equation

valid for all complex numbers s, which relates its values at points s and 1 − s. Here, Γ denotes the gamma function. This functional equation was established by Riemann in his 1859 paper On the Number of Primes Less Than a Given Magnitude and used to construct the analytic continuation in the first place. An equivalent relationship was conjectured by Euler in 1749 for the function

Riemann also found a symmetric version of the functional equation, given by first defining

The functional equation is then given by

(Riemann defined a similar but different function which he called ξ(t).)

[edit] Zeros, the critical line, and the Riemann hypothesis

The functional equation shows that the Riemann zeta function has zeros at −2, −4, ... . These are called the trivial zeros. They are trivial in the sense that their existence is relatively easy to prove, for example, from sin(πs/2) being 0 in the functional equation. The non-trivial zeros have captured far more attention because their distribution not only is far less understood but, more importantly, their study yields impressive results concerning prime numbers and related objects in number theory. It is known that any non-trivial zero lies in the open strip {s ∈ C: 0 < Re(s) < 1}, which is called the critical strip. The Riemann hypothesis, considered to be one of the greatest unsolved problems in mathematics, asserts that any non-trivial zero s has Re(s) = 1/2. In the theory of the Riemann zeta function, the set {s ∈ C: Re(s) = 1/2} is called the critical line. For the Riemann zeta function on the critical line, see Z-function.

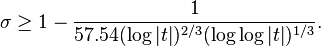

The location of the Riemann zeta function's zeros is of great importance in the theory of numbers. From the fact that all non-trivial zeros lie in the critical strip one can deduce the prime number theorem. A better result[3] is that ζ(σ + it) ≠ 0 whenever|t| ≥ 3 and

The strongest result of this kind one can hope for is the truth of the Riemann hypothesis, which would have many profound consequences in the theory of numbers.

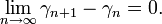

It is known that there are infinitely many zeros on the critical line. Littlewood showed that if the sequence (γn) contains the imaginary parts of all zeros in the upper half-plane in ascending order, then

The critical line theorem asserts that a positive percentage of the nontrivial zeros lies on the critical line.

In the critical strip, the zero with smallest non-negative imaginary part is 1/2 + i14.13472514... Directly from the functional equation one sees that the non-trivial zeros are symmetric about the axis Re(s) = 1/2. Furthermore, the fact that ζ(s) = ζ(s*)* for all complex s ≠ 1 (* indicating complex conjugation) implies that the zeros of the Riemann zeta function are symmetric about the real axis.

The statistics of the Riemann zeta zeros are a topic of interest to mathematicians because of their connection to big problems like the Riemann hypothesis, distribution of prime numbers, etc. Through connections with random matrix theory and quantum chaos, the appeal is even broader. The fractal structure of the Riemann zeta zero distribution has been studied using rescaled range analysis.[4] The self-similarity of the zero distribution is quite remarkable, and is characterized by a large fractal dimension of 1.9. This rather large fractal dimension is found over zeros covering at least fifteen orders of magnitude, and also for the zeros of other L-functions.

[edit] Various properties

For sums involving the zeta-function at integer and half-integer values, see rational zeta series.

[edit] Reciprocal

The reciprocal of the zeta function may be expressed as a Dirichlet series over the Möbius function μ(n):

for every complex number s with real part > 1. There are a number of similar relations involving various well-known multiplicative functions; these are given in the article on the Dirichlet series.

The Riemann hypothesis is equivalent to the claim that this expression is valid when the real part of s is greater than 1/2.

[edit] Universality

The critical strip of the Riemann zeta function has the remarkable property of universality. This zeta-function universality states that there exists some location on the critical strip that approximates any holomorphic function arbitrarily well. Since holomorphic functions are very general, this property is quite remarkable.

[edit] Representations

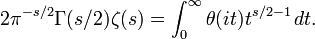

[edit] Mellin transform

The Mellin transform of a function f(x) is defined as

in the region where the integral is defined. There are various expressions for the zeta-function as a Mellin transform. If the real part of s is greater than one, we have

where Γ denotes the Gamma function. By modifying the contour Riemann showed that

for all s, where the contour starts and ends at +∞ and circles the origin once.

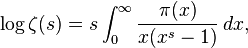

We can also find expressions which relate to prime numbers and the prime number theorem. If π(x) is the prime-counting function, then

for values with

A similar Mellin transform involves the Riemann prime-counting function J(x), which counts prime powers pn with a weight of 1/n, so that  Now we have

Now we have

These expressions can be used to prove the prime number theorem by means of the inverse Mellin transform. Riemann's prime-counting function is easier to work with, and π(x) can be recovered from it by Möbius inversion.

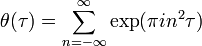

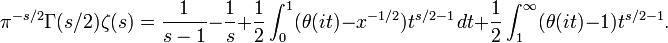

[edit] Theta functions

The Riemann zeta function can be given formally by a divergent Mellin transform

in terms of Jacobi's theta function

However this integral does not converge for any values of s and so needs to be regularized: this gives the following expression for the zeta function:

[edit] Laurent series

The Riemann zeta function is meromorphic with a single pole of order one at s = 1. It can therefore be expanded as a Laurent series about s = 1; the series development then is

The constants γn here are called the Stieltjes constants and can be defined by the limit

The constant term γ0 is the Euler-Mascheroni constant.

[edit] Rising factorial

Another series development using the rising factorial valid for the entire complex plane is

This can be used recursively to extend the Dirichlet series definition to all complex numbers.

The Riemann zeta function also appears in a form similar to the Mellin transform in an integral over the Gauss-Kuzmin-Wirsing operator acting on xs−1; that context gives rise to a series expansion in terms of the falling factorial.

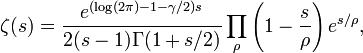

[edit] Hadamard product

On the basis of Weierstrass's factorization theorem, Hadamard gave the infinite product expansion

where the product is over the non-trivial zeros ρ of ζ and the letter γ again denotes the Euler-Mascheroni constant. A simpler infinite product expansion is

This form clearly displays the simple pole at s = 1, the trivial zeros at −2, −4, ... due to the gamma function term in the denominator, and the non-trivial zeros at s = ρ.

[edit] Globally convergent series

A globally convergent series for the zeta function, valid for all complex numbers s except s = 1, was conjectured by Konrad Knopp and proved by Helmut Hasse in 1930:

The series only appeared in an Appendix to Hasse's paper, and did not become generally known until it was rediscovered more than 60 years later (see Sondow, 1994).

Peter Borwein has shown a very rapidly convergent series suitable for high precision numerical calculations. The algorithm, making use of Chebyshev polynomials, is described in the article on the Dirichlet eta function.

[edit] Applications

The zeta function occurs in applied statistics (see Zipf's law and Zipf-Mandelbrot law).

Zeta function regularization is used as one possible means of regularization of divergent series in quantum field theory. In one notable example, the Riemann zeta-function shows up explicitly in the calculation of the Casimir effect.

[edit] Generalizations

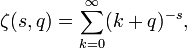

There are a number of related zeta functions that can be considered to be generalizations of Riemann's zeta-function. These include the Hurwitz zeta function

which coincides with Riemann's zeta-function when q = 1 (note that the lower limit of summation in the Hurwitz zeta function is 0, not 1), the Dirichlet L-functions and the Dedekind zeta-function. For other related functions see the articles Zeta function and L-function.

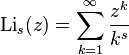

The polylogarithm is given by

which coincides with Riemann's zeta-function when z = 1.

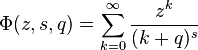

The Lerch transcendent is given by

which coincides with Riemann's zeta-function when z = 1 and q = 0 (note that the lower limit of summation in the Lerch transcendent is 0, not 1).

The Clausen function  that can be chosen as the real or imaginary part of

that can be chosen as the real or imaginary part of

The multiple zeta functions are defined by

One can analytically continue these functions to the n-dimensional complex space. The special values of these functions are called multiple zeta values by number theorists and have been connected to many different branches in mathematics and physics.

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ Bombieri, Enrico. "The Riemann Hypothesis - official problem description". Clay Mathematics Institute. http://www.claymath.org/millennium/Riemann_Hypothesis/riemann.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-10-25.

- ^ C. S. Ogilvy & J. T. Anderson Excursions in Number Theory, pp. 29–35, Dover Publications Inc., 1988 ISBN 0-486-25778-9

- ^ Ford, K. Vinogradov's integral and bounds for the Riemann zeta function, Proc. London Math. Soc. (3) 85 (2002), pp. 565–633

- ^ O. Shanker (2006). "Random matrices, generalized zeta functions and self-similarity of zero distributions". J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 39: 13983–13997. doi:.

[edit] References

- Riemann, Bernhard (1859), "Über die Anzahl der Primzahlen unter einer gegebenen Grösse", Monatsberichte der Berliner Akademie, http://www.maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Riemann/Zeta/. In Gesammelte Werke, Teubner, Leipzig (1892), Reprinted by Dover, New York (1953).

- Jacques Hadamard, Sur la distribution des zéros de la fonction ζ(s) et ses conséquences arithmétiques, Bulletin de la Societé Mathématique de France 14 (1896) pp 199–220.

- Helmut Hasse, Ein Summierungsverfahren für die Riemannsche ζ-Reihe, (1930) Math. Z. 32 pp 458–464. (Globally convergent series expression.)

- E. T. Whittaker and G. N. Watson (1927). A Course in Modern Analysis, fourth edition, Cambridge University Press (Chapter XIII).

- H. M. Edwards (1974). Riemann's Zeta Function. Academic Press. ISBN 0-486-41740-9.

- G. H. Hardy (1949). Divergent Series. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- A. Ivic (1985). The Riemann Zeta Function. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-80634-X.

- A.A. Karatsuba; S.M. Voronin (1992). The Riemann Zeta-Function. W. de Gruyter, Berlin.

- Hugh L. Montgomery; Robert C. Vaughan (2007). Multiplicative number theory I. Classical theory. Cambridge tracts in advanced mathematics. 97. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84903-9. Chapter 10.

- Donald J. Newman (1998). Analytic number theory. GTM. 177. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98308-2. Chapter 6.

- E. C. Titchmarsh (1986). The Theory of the Riemann Zeta Function, Second revised (Heath-Brown) edition. Oxford University Press.

- Jonathan Borwein, David M. Bradley, Richard Crandall (2000). "Computational Strategies for the Riemann Zeta Function" (PDF). J. Comp. App. Math. 121: p.11. http://www.maths.ex.ac.uk/~mwatkins/zeta/borwein1.pdf. (links to PDF file)

- Djurdje Cvijović and Jacek Klinowski (2002). "Integral Representations of the Riemann Zeta Function for Odd-Integer Arguments". J. Comp. App. Math. 142: pp.435–439. doi:. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TYH-451NM96-2&_user=10&_coverDate=05%2F15%2F2002&_alid=509596586&_rdoc=17&_fmt=summary&_orig=search&_cdi=5619&_sort=d&_docanchor=&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=76a759d8292edc715d10b1cb459992f1.

- Djurdje Cvijović and Jacek Klinowski (1997). "Continued-fraction expansions for the Riemann zeta function and polylogarithms". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 125: pp.2543–2550. doi:. http://www.ams.org/proc/1997-125-09/S0002-9939-97-04102-6/home.html.

- Jonathan Sondow, "Analytic continuation of Riemann's zeta function and values at negative integers via Euler's transformation of series", Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 120 (1994) 421–424.

- Jianqiang Zhao (1999). "Analytic continuation of multiple zeta functions". Proc. Amer. Math. Soc. 128: pp.1275–1283. http://www.ams.org/journal-getitem?pii=S0002-9939-99-05398-8.

[edit] External links

- Riemann Zeta Function, in Wolfram Mathworld — an explanation with a more mathematical approach

- Tables of selected zeroes

- File with 1,000,000 zeros and accurate to about 60+ digits (To download compressed archive, click on Download Now... button.)

- Prime Numbers Get Hitched A general, non-technical description of the significance of the zeta function in relation to prime numbers.

- X-Ray of the Zeta Function Visually-oriented investigation of where zeta is real or purely imaginary.

- Formulas and identities for the Riemann Zeta function functions.wolfram.com

- Riemann Zeta Function and Other Sums of Reciprocal Powers, section 23.2 of Abramowitz and Stegun