Gulag

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Gulag was the government agency that administered the penal labor camps of the Soviet Union. Gulag is the Russian acronym for The Chief Administration of Corrective Labor Camps and Colonies (Russian: Главное Управление Исправительно-Трудовых Лагерей и колоний) of the NKVD. Eventually, by metonymy, the usage of "Gulag" began generally denoting the entire penal labor system in the USSR, then any such penal system. In Russian, Gulag is pronounced: (Russian: ГУЛАГ, ![]() listen (help·info))

listen (help·info))

Gulag: A History, by Anne Applebaum,[1] explains: "It was the branch of the State Security that operated the penal system of forced labour camps and associated detention and transit camps and prisons. While these camps housed criminals of all types, the Gulag system has become primarily known as a place for political prisoners and as a mechanism for repressing political opposition to the Soviet state. Though it imprisoned millions, the name became familiar in the West only with the publication of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's 1973 The Gulag Archipelago, which likened the scattered camps to a chain of islands."

There were at least 476 separate camps, some of them comprising hundreds, even thousands of camp units.[2][3] The most infamous complexes were those at arctic or subarctic regions. Today's major industrial cities of the Russian Arctic such as Norilsk, Vorkuta, Kolyma and Magadan, were camps originally built by prisoners and run by ex-prisoners.[4]

More than 14 million (with some authors like Solzhenitsyn estimating the total at more than 40 million) people passed through the Gulag from 1929 to 1953, with a further 6 to 7 million being deported and exiled to remote areas of the USSR.[5] According to Soviet data, a total of 1,053,829 people died in the GULAG from 1934 to 1953, not counting those who died in labor colonies.[6] The total population of the camps varied from 510,307 (in 1934) to 1,727,970 (in 1953).[7].

Most Gulag inmates were not political prisoners, although the political prisoner population was always significant.[8] People could be imprisoned in a Gulag camp for crimes such as unexcused absences from work, petty theft, or anti-government jokes.[9] About half of the political prisoners were sent to Gulag prison camps without trial; per official data, there were more than 2.6 million imprisonment sentences in cases investigated by the secret police, 1921-1953.[10] While the Gulag was radically reduced in size following Stalin’s death in 1953, forced labor camps and political prisoners continued to exist in the Soviet Union right up to the Gorbachev era.[11] However, the camps in Siberia still house a work force of about a million prisoners.[12]

Contents |

[edit] Modern usage and other terminology

Although Gulag originally was the name of a government agency, the acronym acquired the qualities of a noun, denoting: the Soviet system of prison-based, unfree labor — including specific labor, punishment, criminal, political, and transit camps for men, women, and children.

Even more broadly, "Gulag" has come to mean the Soviet repressive system itself, the set of procedures that prisoners once called the "meat-grinder": the arrests, the interrogations, the transport in unheated cattle cars, the forced labor, the destruction of families, the years spent in exile, the early and unnecessary deaths.[13]

Other authors use gulag as denoting all the prisons and internment camps in Soviet history (1917–1991) with the plural gulags. The term's contemporary usage is notably unrelated to the USSR, such as in the expression "North Korea's Gulag".[14]

The word Gulag was not often used in Russian — either officially or colloquially; the predominant terms were the camps (лагеря, lagerya) and the zone (зона, zona), always singular — for the labor camp system and for the individual camps. The official term, "corrective labor camp", was suggested for official politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union use in the session of July 27, 1929.

[edit] History

[edit] Early Soviet period

From 1918, camp-type detention facilities were set up, as a reformed analogy of the earlier system of penal labor (katorgas), operated in Siberia in Imperial Russia. The two main types were "Vechecka Special-purpose Camps" (особые лагеря ВЧК, osobiye lagerya VČK) and forced labor camps (лагеря принудительных работ, lagerya prinuditel'nikh rabot). They were installed for various categories of people deemed dangerous for the state: for common criminals, for prisoners of the Russian Civil War, for officials accused of corruption, sabotage and embezzlement, various political enemies and dissidents, as well as former aristocrats, businessmen and large land owners. These camps, however, were not on the same scale as those in the Stalin era. In 1928 there were 30,000 prisoners in camps, and the authorities were opposed to compelling them to work. In 1927 the official in charge of prison administration wrote that: "The exploitation of prison labour, the system of squeezing ‘golden sweat’ from them, the organization of production in places of confinement, which while profitable from a commercial point of view is fundamentally lacking in corrective significance – these are entirely inadmissible in Soviet places of confinement.”[15]

The legal base and the guidance for the creation of the system of "corrective labor camps" (Russian: исправительно-трудовые лагеря, Ispravitel'no-trudovye lagerya), the backbone of what is commonly referred to as the "Gulag", was a secret decree of Sovnarkom of July 11, 1929 about the use of penal labor that duplicated the corresponding appendix to the minutes of Politburo meeting of June 27, 1929.

As an all-Union institution and a main administration with the OGPU (the Soviet secret police), the GULAG was officially established on April 25, 1930 as the "ULAG" by the OGPU order 130/63 in accordance with the Sovnarkom order 22 p. 248 dated April 7, 1930, and was renamed into GULAG in November.

[edit] Expansion under Stalin

In the early 1930s a drastic tightening of Soviet penal policy caused a significant growth of the prison camp population. During the period of the Great Purge (1937–38) mass arrests caused another upsurge in inmate numbers. During these years hundreds of thousands of individuals were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms on the grounds of one of the multiple passages of the notorious Article 58 of the Criminal Codes of the Union republics, which defined punishment for various forms of "counterrevolutionary activities."

Under NKVD Order № 00447 tens of thousands of GULAG inmates who were accused of "continuing anti-Soviet activity in imprisonment" were executed in 1937-38.

The hypothesis that economic considerations were responsible for mass arrests during the period of Stalinism has been refuted on the grounds of former Soviet archives that have become accessible since the 1990s, although some archival sources also tend to support an economic hypothesis.[16][17] In any case the development of the camp system followed economic lines. The growth of the camp system coincided with the peak of the Soviet industrialization campaign. Most of the camps established to accommodate the masses of incoming prisoners were assigned distinct economic tasks. These included the exploitation of natural resources and the colonization of remote areas as well as the realization of enormous infrastructural facilities and industrial construction projects.

In 1931–32 the Gulag had approximately 200,000 prisoners in the camps; in 1935 — approximately 800,000 in camps and 300,000 in colonies (annual averages), and in 1939 — about 1.3 millions in camps and 350,000 in colonies.[18] . All data about the numbers of prisoners here and below are however taken from documents produced by the NKVD) and are significantly lower than estimates made by historians [19]

[edit] GULAG during World War II

After the German invasion of Poland that marked the start of World War II in 1939, the Soviet Union invaded and annexed eastern parts of the Second Polish Republic. In 1940 the Soviet Union occupied Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Bessarabia and Bukovina. Hundreds of thousands of Polish citizens[20][21] and inhabitants of the other annexed lands, regardless of their ethnic origin, were arrested and sent to the GULAG camps.

Approximately 300,000 Polish prisoners of war were captured by the USSR during and after the Polish Defensive War.[22] Almost all of the captured officers and a large number of ordinary soldiers were then murdered (see Katyn massacre) or sent to GULAG.[23] Of the 10,000-12,000 Poles sent to Kolyma in 1940-1941, most POWs, only 583 men survived, released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East.[24] Out of Anders' 80,000 evacuees from Soviet Union gathered in Great Britain only 310 volunteered to return to Soviet-controlled Poland in 1947.[25]

According to the official data, the total number of sentences for political crimes in USSR in 1939-41 was 211,106.[10] During the war, Gulag populations declined sharply, as a consequence of the mass releases of hundreds of thousands of prisoners who were conscripted and sent directly to the front lines and a steep rise in mortality in 1942–43. In the winter of 1941 a quarter of the Gulag's population died of starvation.[26] 516,841 prisoners died in prison camps in 1941-43.[27][28]

In 1943, the term katorga works (каторжные работы) was reintroduced. They were initially intended for Nazi collaborators, but then other categories of political prisoners (for example, members of deported peoples who fled from exile) were also sentenced to "katorga works". Prisoners sentenced to "katorga works" were sent to Gulag prison camps with the most harsh regime and many of them perished.[28] Other gulag inmates were sentenced to Red Army penal battalions, where they performed extremely hazardous duties such as spearheading Russian offensives, often serving as tramplers, persons who marched or ran over German minefields to clear them for successive Red Army infantry formations.[citation needed]

A total of 427,910 served in penal units from September 1942 to May 1945.[29] These totals should be viewed in comparison to the nearly 34.5 million men and women who served in the Soviet armed forces during the entire period of the war.[29]

[edit] GULAG after World War II

After World War II the number of inmates in prison camps and colonies again rose sharply, reaching approximately 2.5 million people by the early 1950s (about 1.7 million of whom were in camps).

When the war ended in May 1945, as many as two million former Russian citizens were forcefully repatriated (against their will) into the USSR.[30] On 11 February 1945, at the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the United States and United Kingdom signed a Repatriation Agreement with the Soviet Union.[31] One interpretation of this agreement resulted in the forcible repatriation of all Soviets. British and U.S. civilian authorities ordered their military forces in Europe to deport to the Soviet Union up to two million former residents of the Soviet Union, including persons who had left Russia and established different citizenship years before. The forced repatriation operations took place from 1945-1947.[32]

Often, one finds statements that Soviet POWs on their return to the Soviet Union were often treated as traitors (see Order No. 270).[33][34][35] According to some sources, over 1.5 million surviving Red Army soldiers imprisoned by the Germans were sent to the Gulag.[36][37][38] However, that is a confusion with two other types of camps. During and after World War II freed PoWs went to special "filtration" camps. Of these, by 1944, more than 90 per cent were cleared, and about 8 per cent were arrested or condemned to penal battalions. In 1944, they were sent directly to reserve military formations to be cleared by the NKVD. Further, in 1945, about 100 filtration camps were set for repatriated Ostarbeiter, PoWs, and other displaced persons, which processed more than 4,000,000 people. By 1946, 80 per cent civilians and 20 per cent of PoWs were freed, 5 per cent of civilians, and 43 per cent of PoWs re-drafted, 10 per cent of civilians and 22 per cent of PoWs were sent to labor battalions, and 2 per cent of civilians and 15 per cent of the PoWs (226,127 out of 1,539,475 total) transferred to the NKVD, i.e. the Gulag.[39][40]

The Soviets took over former German camps such as the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in which 12,500 Soviet era victims have been uncovered. According to German government estimates "65,000 people died in those Soviet-run camps or in transportation to them."[41] According to German researchers Sachsenhausen should be seen as an integral part of the Gulag system. [42]

For years after World War II, a significant minority[vague] of the inmates were Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians, Latvians and Estonians from lands newly incorporated into the Soviet Union, as well as Finns, Poles, Romanians and others. POWs, in contrast, were kept in a separate camp system (see POW labor in the Soviet Union), which was managed by GUPVI, a separate main administration with the NKVD/MVD[citation needed].

Yet the major reason for the post-war increase in the number of prisoners was the tightening of legislation on property offences in summer 1947 (at this time there was a famine in some parts of the Soviet Union, claiming about 1 million lives), which resulted in hundreds of thousands of convictions to lengthy prison terms, sometimes on the basis of cases of petty theft or embezzlement. At the beginning of 1953 the total number of prisoners in prison camps was more than 2.4 million of which more than 465 thousand were political prisoners.[28]

The state continued to maintain the extensive camp system for a while after Stalin's death in March 1953, although the period saw the grip of the camp authorities weaken and a number of conflicts and uprisings occur (see Bitch Wars; Kengir uprising; Vorkuta uprising).

The amnesty in March 1953 was limited to non-political prisoners and for political prisoners sentenced to not more than 5 years, therefore mostly those convicted for common crimes were then freed. The release of political prisoners started in 1954 and became widespread, and also coupled with mass rehabilitations, after Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of Stalinism in his Secret Speech at the 20th Congress of the CPSU in February 1956.

By the end of the 1950s, virtually all "corrective labor camps" were dissolved. Colonies, however, continued to exist. Officially the GULAG was liquidated by the MVD order 20 of January 25, 1960.

[edit] Conditions

Living and working conditions in the camps varied significantly across time and place, depending, among other things, on the impact of broader events (World War II, countrywide famines and shortages, waves of terror, sudden influx or release of large numbers of prisoners). However, to one degree or another, the large majority of prisoners at most times faced meagre food rations, inadequate clothing, overcrowding, poorly insulated housing; poor hygiene, and insufficient or inadequate health care. The overwhelming majority of prisoners were compelled to perform harsh physical labor.[45] In most periods and economic branches, the degree of mechanization of work processes was significantly lower than in the civilian industry: tools were often primitive and machinery, if existent, short in supply. Officially established work hours were in most periods longer and days off were fewer than for civilian workers. Often official work time regulations were extended by local camp administrators.

In general, the central administrative bodies showed a discernible interest in maintaining the labor force of prisoners in a condition allowing the fulfillment of construction and production plans handed down from above. Besides a wide array of punishments for prisoners refusing to work (which, in practice, were sometimes applied to prisoners that were too enfeebled to meet production quota), they instituted a number of positive incentives intended to boost productivity. These included monetary bonuses (since the early 1930s) and wage payments (from 1950 onwards), cuts of sentences on an individual basis, general early release schemes for norm fulfillment and overfulfillment (until 1939, again in selected camps from 1946 onwards), preferential treatment and privileges for the most productive workers (shock workers or Stakhanovites in Soviet parlance). [46]

A distinctive incentive scheme that included both coercive and motivational elements and was applied universally in all camps consisted in standardized "nourishment scales": the size of the inmates’ ration depended on the percentage of the work quota delivered. Naftaly Frenkel is credited for the introduction of this policy. While it was effective in compelling many prisoners to make serious work efforts, for many a prisoner it had the adverse effect, accelerating the exhaustion and sometimes causing the death of persons unable to fulfill high production quota.

Immediately after the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 the conditions in camps worsened drastically: quotas were increased, rations cut, and medical supplies came close to none, all of which led to a sharp increase in mortality. The situation slowly improved in the final period and after the end of the war.

Considering the overall conditions and their influence on inmates, it is important to distinguish three major strata of Gulag inmates:

- people used to physical labor: "kulaks", osadniks, "ukazniks" (people sentenced for violation of various ukases, such as Law of Spikelets, decree about work discipline, etc.), occasional violators of criminal law

- dedicated criminals

- people unused to physical labour sentenced for various political and religious reasons.

Mortality in GULAG camps in 1934-40 was 4-6 times higher than average in Russia. The estimated total number of those who died in imprisonment in 1930-1953 is 1.76 million, about half of which occurred between 1941-1943 following the German invasion.[47][48]

[edit] Geography

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2007) |

In the early days of Gulag, the locations for the camps were chosen primarily for the ease of isolation of prisoners. Remote monasteries in particular were frequently reused as sites for new camps. The site on the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea is one of the earliest and also most noteworthy, taking root soon after the Revolution in 1918. The colloquial name for the islands, "Solovki", entered the vernacular as a synonym for the labor camp in general. It was being presented to the world as an example of the new Soviet way of "re-education of class enemies" and reintegrating them through labor into the Soviet society. Initially the inmates, the significant part being Russian intelligentsia, enjoyed relative freedom (within the natural confinement of the islands). Local newspapers and magazines were edited and even some scientific research was carried out (e.g., a local botanical garden was maintained, but unfortunately later lost completely). Eventually it turned into an ordinary Gulag camp; in fact some historians maintain that Solovki was a pilot camp of this type. See Solovki for more detail. Maxim Gorky visited the camp in 1929 and published an apology of it.

With the new emphasis on Gulag as the means of concentrating cheap labour, new camps were then constructed throughout the Soviet sphere of influence, wherever the economic task at hand dictated their existence (or was designed specifically to avail itself of them, such as Belomorkanal or Baikal Amur Mainline), including facilities in big cities — parts of the famous Moscow Metro and the Moscow State University new campus were built by forced labor. Many more projects during the rapid industrialization of the 1930s, war-time and post-war periods were fulfilled on the backs of convicts, and the activity of Gulag camps spanned a wide cross-section of Soviet industry.

The majority of Gulag camps were positioned in extremely remote areas of north-eastern Siberia (the best known clusters are Sevvostlag (The North-East Camps) along Kolyma river and Norillag near Norilsk) and in the south-eastern parts of the Soviet Union, mainly in the steppes of Kazakhstan (Luglag, Steplag, Peschanlag). These were vast and sparsely inhabited regions with no roads (in fact, the construction of the roads themselves was assigned to the inmates of specialized railroad camps) or sources of food, but rich in minerals and other natural resources (such as timber). However, camps were generally spread throughout the entire Soviet Union, including the European parts of Russia, Byelorussia, and Ukraine. There were also several camps located outside of the Soviet Union, in Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Mongolia, which were under the direct control of the Gulag.

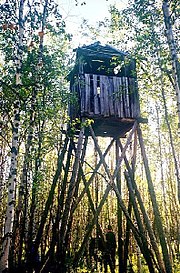

Not all camps were fortified; in fact some in Siberia were marked only by posts. Escape was deterred by the harsh elements, as well as tracking dogs that were assigned to each camp. While during the 1920s and 1930s native tribes often aided escapees, many of the tribes were also victimized by escaped thieves. Tantalized by large rewards as well, they began aiding authorities in the capture of Gulag inmates. Camp guards were also given stern incentive to keep their inmates in line at all costs; if a prisoner escaped under a guard's watch, the guard would often be stripped of his uniform and become a Gulag inmate himself. Further, if an escaping prisoner was shot, guards could be fined amounts that were often equivalent to one or two weeks wages.

In some cases, teams of inmates were dropped to a new territory with a limited supply of resources and left to set up a new camp or die. Sometimes it took several attempts before the next wave of colonists could survive the elements.

The area along the Indigirka river was known as the Gulag inside the Gulag. In 1926, the Oimiakon (Оймякон) village in this region registered the record low temperature of −71.2 °C (−96 °F).

Under the supervision of Lavrenty Beria who headed both NKVD and the Soviet Atom bomb program until his demise in 1953, thousands of zeks were used to mine uranium ore and prepare test facilities on Novaya Zemlya, Vaygach Island, Semipalatinsk, among other sites.

Throughout the period of Stalinism, at least 476 separate camp administrations existed.[49] Since many of these existed only for short periods of time, the number of camp administrations at any given point was lower. It peaked in the early 1950s, when there were more than a hundred different camp administrations across the Soviet Union. Most camp administrations oversaw not just one, but several single camp units, some as many as dozens or even hundreds.[2] The infamous complexes were those at Kolyma, Norilsk, and Vorkuta, all in arctic or subarctic regions. However, prisoner mortality in Norilsk in most periods was actually lower than across the camp system as a whole.[50]

[edit] Special institutions

- Special camps or zones for children (Gulag jargon: "малолетки", maloletki, underaged), for disabled (in Spassk), and for mothers ("мамки", mamki) with babies.

- Camps for "wives of traitors of Motherland" — there was a special category of repression: "Traitor of Motherland Family Member" (ЧСИР, член семьи изменника Родины: ČSIR, člyen sem'i izmennika Rodini).

- Sharashka (шарашка, the goofing-off place) were in fact secret research laboratories, where the arrested and convicted scientists, some of them prominent, were anonymously developing new technologies, and also conducting basic research.

[edit] Influence

[edit] Culture

The Gulag spanned nearly four decades of Soviet and East European history and affected millions of individuals. Its cultural impact was enormous.

The Gulag has become a major influence on contemporary Russian thinking, and an important part of modern Russian folklore. Many songs by the authors-performers known as the bards, most notably Vladimir Vysotsky and Alexander Galich, neither of whom ever served time in the camps, describe life inside the Gulag and glorified the life of "Zeks". Words and phrases which originated in the labor camps became part of the Russian/Soviet vernacular in the 1960s and 1970s.

The memoirs of Alexander Dolgun, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Varlam Shalamov and Yevgenia Ginzburg, among others, became a symbol of defiance in Soviet society. These writings, particularly those of Solzhenitsyn, harshly chastised the Soviet people for their tolerance and apathy regarding the Gulag, but at the same time provided a testament to the courage and resolve of those who were imprisoned.

Another cultural phenomenon in the Soviet Union linked with the Gulag was the forced migration of many artists and other people of culture to Siberia. This resulted in a Renaissance of sorts in places like Magadan, where, for example, the quality of theatre production was comparable to Moscow's.

[edit] Literature

Many eyewitness accounts of Gulag prisoners were published before World War II.

- Julius Margolin's book A Travel to the Land Ze-Ka was finished in 1947, but it was impossible to publish such a book about the Soviet Union at the time, immediately after World War II.

- Gustaw Herling-Grudziński wrote A World Apart, which was translated into English by Andrzej Ciolkosz and published with an introduction by Bertrand Russell in 1951. By describing life in the gulag in a harrowing personal account, it provides an in-depth, original analysis of the nature of the Soviet communist system.

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's book The Gulag Archipelago was not the first literary work about labour camps. His previous book on the subject, "One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich", about a typical day of the GULAG inmate, was originally published in the most prestigious Soviet monthly, Novy Mir, (New World), in November 1962, but was soon banned and withdrawn from all libraries. It was the first work to demonstrate the Gulag as an instrument of governmental repression against its own citizens on a massive scale. The First Circle, an account of three days in the lives of prisoners in the Marfino sharashka or special prison was submitted for publication to the Soviet authorities shortly after One Day in the Life but was rejected and later published abroad in 1968.

- János Rózsás, Hungarian writer, often referred to as the Hungarian Solzhenitsyn, wrote a lot of books and articles on the issue of GULAG.

- Zoltan Szalkai, Hungarian documentary filmmaker made several films of gulag camps.

- Karlo Štajner, an Austrian communist active in the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia and manager of Comintern Publishing House in Moscow from 1932–39, was arrested one night and taken from his Moscow home under accusation of anti-revolutionary activities. He spent the following 20 years in camps from Solovki to Norilsk. After USSR–Yugoslavian political normalization he was re-tried and quickly found innocent. He left the Soviet Union with his wife, who had been waiting for him for 20 years, in 1956 and spent the rest of his life in Zagreb, Croatia. He wrote an impressive book entitled 7000 days in Siberia.

- Dancing Under the Red Star by Karl Tobien (ISBN 1-4000-7078-3) tells the story of Margaret Werner, a young athletic girl who moves to Russia right before the start of Stalin's terror. She faces many hardships, as her father is taken away from her and imprisoned. Werner is the only American woman who survived the Gulag to tell about it.

- "Alexander Dolgun's Story: An American in the Gulag." (ISBN 0-394-49497-0), of a member of the US Embassy, and "I Was a Slave in Russia" (ISBN 0-815-95800-5), an American factory owner's son, were two more American citizens interned who wrote of their ordeal. Both were interned due to their American citizenship for about 8 years circa 1946–55.

[edit] Colonization

Soviet state documents show that among the goals of the GULAG was colonization of sparsely populated remote areas. To this end, the notion of "free settlement" was introduced.

When well-behaved persons had served the majority of their terms, they could be released for "free settlement" (вольное поселение, volnoye poseleniye) outside the confinement of the camp. They were known as "free settlers" (вольнопоселенцы, volnoposelentsy, not to be confused with the term ссыльнопоселенцы,ssyl'noposelentsy, "exile settlers"). In addition, for persons who served full term, but who were denied the free choice of place of residence, it was recommended to assign them for "free settlement" and give them land in the general vicinity of the place of confinement.

This implement was also inherited from the katorga system.

[edit] Life after term served

Persons who served a term in a camp or in a prison were restricted from taking a wide range of jobs. Concealment of a previous imprisonment was a triable offence. Persons who served terms as "politicals" were nuisances for "First Departments" (Первый Отдел, Pervyj Otdel, outlets of the secret police at all enterprises and institutions), because former "politicals" had to be monitored.

Many people released from camps were restricted from settling in larger cities.

[edit] Lack of prosecution

It has often been asked why there has been nothing along the lines of the Nuremberg Trials for those guilty of atrocities at the Gulag camps. Two recent books, reviewed by Peter Rollberg in the Moscow Times,[51] cast some light on this. Tomasz Kizny's Gulag: Life and Death Inside the Soviet Concentration Camps 1917-1990 details the history of the labour camps over the years while Oleg Khlevniuk's The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror presents records of confidential memos, official resolutions, individual testimonies and tabulated statistics. Rollberg explains how both books contribute to our understanding of why there were no post-Communism trials. "The gulag had already killed tens of thousands of its own most ardent killers. Again and again, yesterday's judges were declared today's criminals, so that Soviet society never had to own up to its millions of state-backed murders."

[edit] Gulag memorials

The Memorial pictured below in St Petersburg is made of a boulder from the Solovki camp — the first prison camp in the Gulag system. People gather here every year on the Day of Victims of the Repression (October 30).

[edit] See also

[edit] On Wikipedia

- List of Gulag camps

- List of uprisings in the Gulag

- Kolyma

- 101st kilometre

- Article 58 (RSFSR Penal Code)

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union

- Mass graves in the Soviet Union

- Soviet political repressions

- Memorial (society)

- Kengir uprising

- Norilsk uprising, an uprising in Norilsk "Gorlag" (mining camp), 1953

- Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Forced labor camps elsewhere

-

- Devil's Island (France)

- The Vietnamese Gulag

- Extermination through labour (Nazi Germany)

- Danube-Black Sea Canal (Communist Romania)

- Katorga (Russian Empire)

- Laogai (China)

[edit] References

- ^ by, Written (2003-04-29). "Gulag: A History, by Anne Applebaum". Randomhouse.com. http://www.randomhouse.com/acmart/catalog/display.pperl?isbn=9780767900560. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b Anne Applebaum — Inside the Gulag[dead link]

- ^ Gulag The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed.

- ^ "Gulag: a History of the Soviet Camps". Arlindo-correia.com. http://www.arlindo-correia.com/041003.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ According to Conquest, between 1939 and 1953, there was, in the work camps, a 10% death rate per year, rising to 20% in 1938. Robert Conquest in Victims of Stalinism: A Comment. Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 49, No. 7 (Nov., 1997), pp. 1317-1319 states:"We are all inclined to accept the Zemskov totals (even if not as complete) with their 14 million intake to Gulag 'camps' alone, to which must be added 4-5 million going to Gulag 'colonies', to say nothing of the 3.5 million already in, or sent to, 'labour settlements'. However taken, these are surely 'high' figures."

- ^ Getty, Rittersporn, Zemskov. Victims of the Soviet Penal System in the Pre-War Years: A First Approach on the Basis of Archival Evidence. The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 4 (Oct., 1993), pp. 1017-1049, see also http://www.etext.org/Politics/Staljin/Staljin/articles/AHR/AHR.html Politics Stalin, Mario Sousa - This project is intended to reveal the lies of propaganda concerning Stalin and the USSR

- ^ Getty, Rittersporn, Zemskov, op. cit.

- ^ "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. http://publicist.n1.by/articles/repressions/repressions_gulag2.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "What Were Their Crimes?". Gulaghistory.org. http://gulaghistory.org/nps/onlineexhibit/stalin/crimes.php. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. http://publicist.n1.by/articles/repressions/repressions_organy1.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ News Release: Forced labor camp artifacts from Soviet era on display at NWTC[dead link]

- ^ Carl De Keyzer, Zona at the Impressions Gallery, BBC

- ^ Anne Applebaum. "GULAG: a history". http://www.anneapplebaum.com/gulag/intro.html. Retrieved on 2007-12-21.

- ^ Antony Barnett (2004-02-01). "Revealed: the gas chamber horror of North Korea's gulag". Guardian Unlimited. http://www.guardian.co.uk/korea/article/0,2763,1136483,00.html#article_continue. Retrieved on 2007-12-21.

- ^ D.J. Dallin and B.I. Nicolayesky, Forced Labour in Soviet Russia, London 1948, p. 153.

- ^ See, e.g. Michael Jakobson, Origins of the GULag: The Soviet Prison Camp System 1917–34, Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1993, p. 88.

- ^ See, e.g. Galina M. Ivanova, Labor Camp Socialism: The Gulag in the Totalitarian System, Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000, Chapter 2.

- ^ Cf, e.g., Istorija stalinskogo Gulaga: konec 1920-kh - pervaia polovina 1950-kh godov; sobranie dokumentov v 7 tomakh, ed. by V. P. Kozlov et al., Moskva: ROSSPEN 2004, vol. 4: Naselenie GULAGa

- ^ See for example Conquest, op. cit, or Davies, op. cit.

- ^ Franciszek Proch, Poland's Way of the Cross, New York 1987 P.146

- ^ Project In Posterum [1]

- ^ Encyklopedia PWN 'KAMPANIA WRZEŚNIOWA 1939', last retrieved on 10 December 2005, Polish language

- ^ (English) Marek Jan Chodakiewicz (2004). Between Nazis and Soviets: Occupation Politics in Poland, 1939-1947. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739104845.

- ^ "Robert Conquest 1978. Kolyma: The Arctic Death Camps. OUP". My.telegraph.co.uk. http://my.telegraph.co.uk/beanbean/blog/2008/05/02/a_polish_life_5_starobielsk_and_the_transsiberian_railway. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Michael Hope - "Polish deportees in the Soviet Union"". Wajszczuk.v.pl. http://www.wajszczuk.v.pl/english/drzewo/czytelnia/michael_hope.htm. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ GULAG: a History, Anne Applebaum

- ^ Zemskov, Gulag, Sociologičeskije issledovanija, 1991, No. 6, pp. 14-15.

- ^ a b c "Repressions". Publicist.n1.by. http://publicist.n1.by/articles/repressions/repressions_gulag1.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b G.F. Krivosheev, ‘Soviet Casualties and Combat Losses in the twentieth century’, London, Greenhill Books, 1997, ISBN 1853672807 (ISBN13 9781853672804).

- ^ Mark Elliott. "The United States and Forced Repatriation of Soviet Citizens, 1944-47," Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 88, No. 2 (June, 1973), pp. 253-275.

- ^ "Repatriation - The Dark Side of World War II". Fff.org. http://www.fff.org/freedom/0895a.asp. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "''Forced Repatriation to the Soviet Union: The Secret Betrayal''". Hillsdale.edu. 1939-09-01. http://www.hillsdale.edu/news/imprimis/archive/issue.asp?year=1988&month=12. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "''The warlords: Joseph Stalin''". Channel4.com. 1953-03-06. http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/t-z/warlords1stalin.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Remembrance (Zeithain Memorial Grove)". Stsg.de. 1941-08-16. http://www.stsg.de/main/zeithain/geschichte/gedenken/index_en.php. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Soviet Prisoners of War: Forgotten Nazi Victims of World War II". Historynet.com. 1941-09-08. http://www.historynet.com/wars_conflicts/world_war_2/3037296.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Sorting Pieces of the Russian Past". Hoover.org. 2002-10-23. http://www.hoover.org/publications/digest/3063246.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Patriots ignore greatest brutality". Smh.com.au. 2007-08-13. http://www.smh.com.au/news/opinion/patriots-ignore-greatest-brutality/2007/08/12/1186857342382.html?page=2. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Joseph Stalin killer file". Moreorless.au.com. 2001-05-23. http://www.moreorless.au.com/killers/stalin.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ (“Военно-исторический журнал” (“Military-Historical Magazine”), 1997, №5. page 32)

- ^ Земское В.Н. К вопросу о репатриации советских граждан. 1944-1951 годы // История СССР. 1990. № 4 (Zemskov V.N. On repatriation of Soviet citizens. Istoriya SSSR., 1990, No.4

- ^ Germans Find Mass Graves at an Ex-Soviet Camp New York Times, September 24, 1992

- ^ Ex-Death Camp Tells Story Of Nazi and Soviet Horrors New York Times, December 17, 2001

- ^ http://www.etext.org/Politics/Staljin/Staljin/articles/AHR/AHR.html

- ^ http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2007/0313/tema06.php

- ^ The Gulag Collection: Paintings of Nikolai Getman[dead link]

- ^ Leonid Borodkin and Simon Ertz 'Forced Labour and the Need for Motivation: Wages and Bonuses in the Stalinist Camp System', Comparative Economic Studies, June 2005, Vol.47, Iss. 2, pp. 418–436.

- ^ "Demographic Losses Due to Repressions", by Anatoly Vishnevsky, Director of the Center for Human Demography and Ecology, Russian Academy of Sciences, (Russian)

- ^ "The History of the GULAG", by Oleg V.Khlevniuk

- ^ "Система исправительно-трудовых лагерей в СССР". Memo.ru. http://www.memo.ru/history/nkvd/gulag/gulag3.htm. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ "Coercion versus Motivation: Forced Labor in Norilsk" (PDF). http://media.hoover.org/documents/0817939423_75.pdf. Retrieved on 2009-01-06.

- ^ Prosecuting the Gulag, Moscow Times, January 21, 2005, retrieved 18 January 2007.

[edit] Literature

- Orlando Figes, The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia, Allen Lane, 2007, hardcover, 740 pp., ISBN 0141013516.

- Anne Applebaum, Gulag: A History, Broadway Books, 2003, hardcover, 720 pp., ISBN 0-7679-0056-1.

- Walter Ciszek, With God in Russia, Ignatius Press, 1997, 433 pp., ISBN 0-8987-0574-6.

- Nicolas Werth, "A State Against Its People: Violence, Repression, and Terror in the Soviet Union, in Stephane Courtois et al., eds., The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Harvard University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-674-07608-7, pp. 33-260.

- Alexander Dolgun, Patrick Watson, "Alexander Dolgun's story: An American in the Gulag", NY, Knopf, 1975, 370 pp., ISBN 978-0394494975.

- Simon Ertz, Zwangsarbeit im stalinistischen Lagersystem: Eine Untersuchung der Methoden, Strategien und Ziele ihrer Ausnutzung am Beispiel Norilsk, 1935-1953, Duncker & Humblot, 2006, 273 pp., ISBN 9783428118632.

- J. Arch Getty, Oleg V. Naumov, The Road to Terror: Stalin and the Self-Destruction of the Bolsheviks, 1932-1939, Yale University Press, 1999, 635 pp., ISBN 0-300-07772-6.

- Gustaw Herling-Grudzinski, A World Apart: Imprisonment in a Soviet Labor Camp During World War II, Penguin, 1996, 284 pp., ISBN 0-14-025184-7.

- Paul R. Gregory, Valery Lazarev, eds, The Economics of Forced Labour: The Soviet Gulag, Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2003, ISBN 0-8179-3942-3, full text available online at "Hoover Books Online"

- Adam Hochschild, The Unquiet Ghost: Russians Remember Stalin (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), 304 pp., paperback: ISBN 0-618-25747-0.

- Oleg V. Khlevniuk, The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror, Yale University Press, 2004, hardcover, 464 pp., ISBN 0-300-09284-9.

- Tomasz Kizny, Gulag: Life and Death Inside the Soviet Concentration Camps 1917-1990, Firefly Books Ltd., 2004, 496 pp., ISBN 1-55297-964-4.

- Jacques Rossi, The Gulag Handbook: An Encyclopedia Dictionary of Soviet Penitentiary Institutions and Terms Related to the Forced Labour Camps, 1989, ISBN 1-55778-024-2.

- Istorija stalinskogo Gulaga: konec 1920-kh - pervaia polovina 1950-kh godov; sobranie dokumentov v 7 tomach, ed. by V. P. Kozlov et al., Moskva: ROSSPEN 2004-5, 7 vols. ISBN 5-8243-0604-4

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

- The Gulag Archipelago, Harper & Row, 660 pp., ISBN 0-06-080332-0.

- The Gulag Archipelago: Two, Harper & Row, 712 pp., ISBN 0-06-080345-2.

- "The Literature of Stalin's Repressions" in Azerbaijan International, Vol 14:1 (Spring 2006)

[edit] Memoirs

- Ayyub Baghirov (1906-1973), Bitter Days of Kolyma

- Murtuz Sadikhli (1927-1997), Memory of Blood

- Ummugulsum Sadigzade (died 1944), Prison Diary: Tears Are My Only Companions

- Ummugulsum Sadigzade (died 1944), Letters from Prison to her Young Children

- Remembering Stalin - Azerbaijan International 13.4 (Winter 2005)

- Eugenia Ginzburg, Journey into the whirlwind, Harvest/HBJ Book, 2002, 432 pp., ISBN 0156027518.

- Eugenia Ginzburg, Within the Whirlwind, Harvest/HBJ Book, 1982, 448 pp., ISBN 0156976498.

- John H. Noble, I Was a Slave in Russia, Broadview, Illinois: Cicero Bible Press, 1961).

- Varlam Shalamov, Kolyma Tales, Penguin Books, 1995, 528 pp., ISBN 0-14-018695-6.

- Danylo Shumuk,

- Life sentence: Memoirs of a Ukrainian political prisoner, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Study, 1984, 401 pp., ISBN 978-0920862179.

- Za Chidnim Obriyam -(Beyond The Eastern Horizon),Paris, Baltimore: Smoloskyp, 1974, 447 pp.

- Solzhenitsyn's, Shalamov's, Ginzburg's works at Lib.ru (in original Russian)

[edit] Fiction

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

- One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Signet Classic, 158 pp., ISBN 0-451-52310-5.

- The First Circle, Northwestern University Press, 580 pp., ISBN 978-0810115903.

- Chabua Amirejibi, Gora Mborgali. Tbilisi, Georgia: Chabua, 2001, 650 pp., ISBN 99940-734-1-9.

- Mehdi Husein (1905-1965), "Underground Rivers Flow Into the Sea" (Excerpts - First Novel About Exile to the Gulag by an Azerbaijani Writer)

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: ГУЛАГ |

- GULAG: Many Days, Many Lives, Online Exhibit, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University

- Gulag: Forced Labor Camps, Online Exhibition, Open Society Archives

- Map of labour camps all over the USSR

- Virtual Gulag Museum

- Gulag prisoners at work, 1936-1937 Photoalbum at NYPL Digital Gallery

- The GULAG, Revelations from the Russian Archives at Library of Congress

- GULAG 113, Canadian documentary film about Estonians in the GULAG, website includes photos video.

- Gulag Photo album (prisoners of Kolyma and Chukotka labour camps, 1951-55)

- Pages about the Kolyma camps and the evolution of GULAG

- The Soviet Gulag Era in Pictures - 1927 through 1953