Edward Gorey

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article is missing citations or needs footnotes. Please help add inline citations to guard against copyright violations and factual inaccuracies. (December 2007) |

| Edward St. John Gorey | |

| Born | February 22, 1925 |

| Died | April 15, 2000 (aged 75) Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Writer / Illustrator |

| Training | Mainly self-taught; briefly: The School of The Art Institute of Chicago |

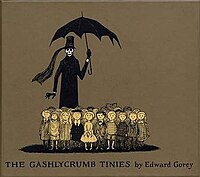

| Works | Gashlycrumb Tinies, Doubtful Guest, Animation introducing "Mystery" on PBS |

| Awards | Tony Award (costume design) |

Edward St. John Gorey (ca. February 22, 1925 – April 15, 2000) was an American writer and artist noted for his macabre illustrated books.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Biography

Edward St. John Gorey was born in Chicago. His parents, Helen Dunham Garvey and Edward Lee Gorey,[2] divorced in 1936 when he was 11, then remarried in 1952 when he was 27. One of his stepmothers was Corinna Mura (1909-65), a cabaret singer who had a small role in the classic film Casablanca as the woman playing the guitar while singing "La Marseillaise" at Rick's Café Américain. His father was briefly a journalist. Gorey's maternal great-grandmother, Helen St. John Garvey, was a popular 19th century greeting card writer and artist, from whom he claimed to have inherited his talents.

Gorey attended a variety of local grade schools and then the Francis W. Parker School. He spent 1944 to 1946 in the Army at Dugway Proving Ground in Utah, and then attended Harvard University from 1946 to 1950, where he studied French and roomed with poet Frank O'Hara.

Although he would frequently state that his formal art training was "negligible," Gorey studied art for one semester at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1943, eventually becoming a professional illustrator. From 1953 to 1960, he lived in New York City and worked for the Art Department of Doubleday Anchor, illustrating book covers and in some cases adding illustrations to the text. He illustrated works as diverse as Dracula by Bram Stoker, The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells, and Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats by T. S. Eliot. In later years he produced cover illustrations for many children's books by John Bellairs, as well as books in several series begun by Bellairs and continued by other authors after his death.

His first independent work, The Unstrung Harp, was published in 1953. He also published under pen names that were anagrams of his first and last names, such as Ogdred Weary, Dogear Wryde, Ms. Regera Dowdy, and dozens more. His books also feature the names Eduard Blutig ("Edward Gory"), a German language pun on his own name, and O. Müde (German for O. Weary).

The New York Times credits bookstore owner Andreas Brown and his store, the Gotham Book Mart, with launching Gorey's career: "it became the central clearing house for Mr. Gorey, presenting exhibitions of his work in the store's gallery and eventually turning him into an international celebrity." [3]

Gorey's illustrated (and sometimes wordless) books, with their vaguely ominous air and ostensibly Victorian and Edwardian settings, have long had a cult following. Gorey became particularly well-known through his animated introduction to the PBS series Mystery! in 1980, as well as his designs for the 1977 Broadway production of Dracula, for which he won a Tony Award for Best Costume Design. (He was also nominated for Best Scenic Design.)

The settings and style of Gorey's work have caused many people to assume he was British; in fact, he never visited Britain, and he almost never traveled. In later years, he lived year-round in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, where he wrote and directed numerous evening-length entertainments, often featuring his own papier-mâché puppets, in an ensemble known as La Theatricule Stoique. His major theatrical work was the libretto for an Opera Seria for Hand Puppets titled The White Canoe, with a score by the composer Daniel James Wolf. Based on the Lady of the Lake legend, the opera premiered posthumously. On August 13, 1987, his play Lost Shoelaces premiered in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. In the early 1970s, Gorey wrote an unproduced screenplay for a silent film, The Black Doll.

Gorey was noted for his fondness for ballet (for many years, he religiously attended all performances of the New York City Ballet), fur coats, tennis shoes, and cats, of which he had many. All figure prominently in his work. His knowledge of literature and films was unusually extensive, and in his interviews, he named Jane Austen, Agatha Christie, Francis Bacon, George Balanchine, Balthus, Louis Feuillade, Ronald Firbank, Lady Murasaki Shikibu, Robert Musil, Yasujiro Ozu, Anthony Trollope, and Johannes Vermeer as some of his favorite artists. Gorey was also an unashamed pop-culture junkie, avidly following soap operas and TV comedies like Petticoat Junction and Cheers, and he had particular affection for dark genre series like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Batman: The Animated Series, and The X-Files; he once told an interviewer that he so enjoyed the Batman series that it was influencing the visual style of one of his upcoming books. Gorey treated TV commercials as an artform in themselves, even taping his favorites for later study. But Gorey was especially fond of movies, and for a time he did regular and very waspish reviews for the Soho Weekly under the pseudonym Wardore Edgy.

Although Gorey's books were popular with children, he did not associate with children much and had no particular fondness for them. Gorey never married, professed to have little interest in romance, and never discussed any specific romantic relationships in interviews. In the book The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, published after Gorey's death, his friend Alexander Theroux reported that when Gorey was pressed on the matter of his sexual orientation, he said that even he was not sure whether he was gay or straight. When asked what his sexual preferences were in an interview, he said,

| “ | I'm neither one thing nor the other particularly. I am fortunate in that I am apparently reasonably undersexed or something...I've never said that I was gay and I've never said that I wasn't...what I'm trying to say is that I am a person before I am anything else.... | ” |

It is possible that Gorey was asexual. Theroux paints a portrait of a man who lived a fairly solitary existence by choice, friendly, generous, and apparently comfortable with strangers, but strongly preferring to be alone most of the time.

From 1996 to his death in April 2000, the normally reclusive artist was the subject of a direct cinema-style documentary directed by Christopher Seufert. This was not yet released as of 2008. He was interviewed on Tribute To Edward Gorey, an hourlong community cable television show produced by artist and friend Joyce Kenney. He contributed his videos and personal thoughts. Edward served as judge in Yarmouth art shows and enjoyed activities at the local cable station, studying computer art and serving as cameraman on many Yarmouth shows. His Cape Cod house is called Elephant House and is the subject of a photography book titled Elephant House: Or, the Home of Edward Gorey, with photographs and text by Kevin McDermott. The house is now the Edward Gorey House Museum.[4]

Gorey's work defies easy classification. He is typically described as an illustrator, but this merely scratches the surface. His combination of words and pictures has led some to classify him as having been a cartoonist, while others regard him primarily as a writer who drew, or an illustrator who wrote. His books can be found in the humor and cartoon sections of major bookstores, but books like The Object Lesson have earned serious critical respect as works of surrealist art. His endless experimentations—creating books that were wordless, books that were literally matchbox-sized, pop-up books, books entirely populated by inanimate objects, and more—complicates matters still further, not to mention the thorny issue of whether his books are best classed as literature for children or for adults. As Gorey told Richard Dyer of The Boston Globe, "Ideally, if anything [was] any good, it would be indescribable." Gorey classified his own work as literary nonsense, the genre made most famous by Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. Gorey seemed to love the precision involved in this genre, and, in response to the accusation of being gothic, he stated, "If you're doing nonsense it has to be rather awful, because there'd be no point. I'm trying to think if there's sunny nonsense. Sunny, funny nonsense for children—oh, how boring, boring, boring. As Schubert said, there is no happy music. And that's true, there really isn't. And there's probably no happy nonsense, either." [5] Much of his work fits rather well into the genre of literary nonsense, yet there is no one category that can encompass the great variety of style and subject in his many books.

[edit] Bibliography

Gorey wrote more than 100 books, including:

|

|

Many of Gorey's works were published obscurely and are difficult to find (and priced accordingly).[citation needed] However, the following four omnibus editions collect much of his material. Because his original books are rather short, these editions may contain 15 or more in each volume.

- Amphigorey, 1972 (ISBN 0-399-50433-8) - contains The Unstrung Harp, The Listing Attic, The Doubtful Guest, The Object-Lesson, The Bug Book, The Fatal Lozenge, The Hapless Child, The Curious Sofa, The Willowdale Handcar, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Insect God, The West Wing, The Wuggly Ump, The Sinking Spell, and The Remembered Visit

- Amphigorey Too, 1975 (ISBN 0-399-50420-6) - contains The Beastly Baby, The Nursery Frieze, The Pious Infant, The Evil Garden, The Inanimate Tragedy, The Gilded Bat, The Iron Tonic, The Osbick Bird, The Chinese Obelisks (bis), The Deranged Cousins, The Eleventh Episode, [The Untitled Book], The Lavender Leotard, The Disrespectful Summons, The Abandoned Sock, The Lost Lions, Story for Sara [by Alphonse Allais], The Salt Herring [by Charles Cros], Leaves from a Mislaid Album, and A Limerick

- Amphigorey Also, 1983 (ISBN 0-15-605672-0) - contains The Utter Zoo, The Blue Aspic, The Epiplectic Bicycle, The Sopping Thursday, The Grand Passion, Les Passementeries Horribles, The Eclectic Abecedarium, L'Heure bleue, The Broken Spoke, The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, The Glorious Nosebleed, The Loathsome Couple, The Green Beads, Les Urnes Utiles, The Stupid Joke, The Prune People, and The Tuning Fork

- Amphigorey Again, 2006 (ISBN 0-15-101107-9) - contains The Galoshes of Remorse, Signs of Spring, Seasonal Confusion, Random Walk, Category, The Other Statue, 10 Impossible Objects (abridged), The Universal Solvent (abridged), Scenes de Ballet, Verse Advice, The Deadly Blotter, Creativity, The Retrieved Locket, The Water Flowers, The Haunted Tea-Cosy, Christmas Wrap-Up, The Headless Bust, The Just Dessert, The Admonitory Hippopotamus, Neglected Murderesses, Tragedies Topiares, The Raging Tide, The Unknown Vegetable, Another Random Walk, Serious Life: A Cruise, Figbash Acrobate, La Malle Saignante, and The Izzard Book

He also illustrated more than 50 works by other authors, including Samuel Beckett, Edward Lear, John Bellairs, H. G. Wells, Alain-Fournier, T. S. Eliot, Hilaire Belloc, Muriel Spark, Florence Parry Heide, and John Ciardi.

[edit] Legacy

Gorey's influence is readily apparent in the work of many artists working in many different media. In 1999, Edward Gorey designed the front and rear cover art for his long time friend Clif Hanger, the founder-lyricist-vocalist for the Cape Cod, Massachusetts-based punk rock band the Freeze. The album, titled One False Move, was released in late 1999. Gorey also co-wrote with Clif Hanger the lyrics to one of the band's songs titled "Alien Heads." Cartoonists such as Dame Darcy and Tony Millionaire tell dark, whimsical tales with plenty of Gorey-esque visual flourishes; Hollywood's Tim Burton's directorial style owes much to Gorey and various musical acts have displayed influence. For example, Mark Romanek's music video for the Nine Inch Nails song "The Perfect Drug" was designed specifically to look like a Gorey book, with familiar Gorey elements including oversize urns, topiary plants, and glum, pale characters in full Edwardian costume.[6] Also, Caitlín R. Kiernan has published a short story titled "A Story for Edward Gorey" (Tales of Pain and Wonder, 2000), which features Gorey's black doll.

A more direct link to Gorey's influence on the music world is evident in The Gorey End, an album recorded in 2003 by the Tiger Lillies and the Kronos Quartet. This album was a collaboration with Gorey, who liked previous work by The Tiger Lillies so much that he sent them a large box of his unpublished work, which were then adapted and turned into songs. Gorey died before hearing the finished album.

In 1976 jazz composer Michael Mantler recorded an album called The Hapless Child (Watt/ECM) with Robert Wyatt, Terje Rypdal, Carla Bley and Jack DeJohnette. It contains musical adaptations of The Sinking Spell, The Object Lesson, The Insect God, The Doubtful Guest, The Remembered Visit and The Hapless Child. The three last songs have also been published on his 1987 Live album with Jack Bruce, Rick Fenn and Nick Mason.

There is a reference to Gorey in Andrew Bird's song "Measuring Cups," from his album The Mysterious Production of Eggs.

The Perry Bible Fellowship web comic featured a strip called "The Throbblefoot Aquarium" which features Gorey-esque illustrations with a small note reading "apologies, Edward Gorey."

The opening titles of the PBS series Mystery! is based on Gorey's art, in an animated sequence co-directed by Derek Lamb.

In the last few decades of his life, Gorey merchandise became quite popular, with stuffed dolls, cups, stickers, posters, and other items available at malls around the USA.

The collectible card game Gloom uses artwork inspired by Gorey's style.

A Film entitled "The Unfortunate Gift: An Homage to Edward Gorey" by Mark G.E., member of Cyberchump.

The Los Angeles horror band Creature Feature released an Edward Gorey-inspired song titled "A Gorey Demise" based on "The Gashlycrumb Tinies".

In episode 392 of The Simpsons, "Yokel Chords", Bart tells a fabricated tale about a former cafeteria worker named Dark Stanley who snapped one day and cooked school children. The sequence during Bart's narration is a clear homage to Gorey's macabre illustration style.

In March 2008, a UK-based theatre company called Hoipolloi premiered a stage production inspired by The Doubtful Guest.

The Jim Henson Company announced plans to produce a feature film based on The Doubtful Guest to be directed by Brad Peyton. The release is planned for sometime during 2009.

Los Angeles based improv troupe "The Doubtful Guests" perform a partially Gorey-inspired show as characters who perished in a London brothel fire.

Gorey has become an iconic figure in the Goth subculture. Events themed on his works and decorated in his characteristic style are common in the more Victorian-styled elements of the subculture, notably the costumed Edwardian Balls held annually in San Francisco and Los Angeles, which include performances based on his works. The "Edwardian" in this case refers less to the Edwardian period of history than to Gorey himself, whose characters are depicted as wearing fashion styles ranging from those of the mid-19th century to the 1930s.

Gorey's book, "The Gashlycrumb Tinies", was shown on an episode of Degrassi: The Next Generation called "Take My Breath Away" where one of the main characters, Ellie Nash was shown reading the book, and a short conversation of Gorey was vocalized between Ellie and Marco.

[edit] Pseudonyms

Gorey was very fond of word games, particularly anagrams. He wrote many of his books under pseudonyms that were usually anagrams of his own name (most famously Ogdred Weary). Some of these are listed below, with the corresponding book title(s). Eduard Blutig is also a word game: "Blutig" is German (the language from which these two books were purportedly translated) for "bloody," which is a synonym for "gory."

- Ogdred Weary - The Curious Sofa, The Beastly Baby

- Mrs. Regera Dowdy - The Pious Infant

- Eduard Blutig - The Evil Garden (translated from Der Böse Garten by Mrs. Regera Dowdy), The Tuning Fork (translated from Der Zeitirrthum by Mrs. Regera Dowdy)

- Raddory Gewe - The Eleventh Episode

- Dogear Wryde - The Broken Spoke/Cycling Cards

- E. G. Deadworry - The Awdrey-Gore Legacy

- D. Awdrey-Gore - The Toastrack Enigma, The Blancmange Tragedy, The Postcard Mystery, The Pincushion Affair, The Toothpaste Murder, The Dustwrapper Secret (Note: These books, although attributed to Awdrey-Gore in Gorey's book The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, were not really written.)

- Edward Pig - The Untitled Book

- Wardore Edgy

- Madame Groeda Weyrd - The Fantod Deck

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ Kelley, Tina (April 16 2000), "Edward Gorey, Eerie Illustrator And Writer, 75", The New York Times, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C05E1D81731F935A25757C0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink

- ^ Ancestry of Edward Gorey

- ^ Gussow, Mel (April 17 2000), "Edward Gorey, Artist and Author Who Turned the Macabre Into a Career, Dies at 75", The New York Times, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9500E1DE1431F934A25757C0A9669C8B63&sec=&spon=&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink

- ^ McDermott, Kevin. Elephant House: Or, the Home of Edward Gorey. Pomegranate Communications (2003). ISBN 0764924958 and ISBN 978-0764924958

- ^ Schiff, Stephen. “Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense.” The New Yorker, November 9, 1992: 84-94, p. 89.

- ^ Interview with Mark Romanek, in the currently unreleased documentary by Christopher Seufert.

[edit] References

- The World of Edward Gorey, Clifford Ross and Karen Wilkin, Henry N. Abrams Inc., 1996 (ISBN 0-8109-3988-6). Interview and monograph.

- Ascending Peculiarity, ed. Karen Wilkin, Harcourt Inc., 2001 (ISBN 0-15-100504-4). Selected interviews from 1973 to 1999, plus miscellaneous quotes and illustrations.

- Elephant House: Or, the Home of Edward Gorey, Kevin McDermott, Foreword by John Updike, Pomegranate, 2003 (ISBN 0-7649-2495-8). Photographic study of Gorey's home as it was at the time of his death. Includes biographical text of his life on Cape Cod, plus miscellaneous quotes and illustrations.

- The Strange Case of Edward Gorey, Alexander Theroux, Fantagraphics Books, 2000 (ISBN 1-56097-385-4). Biography and reminiscence by Theroux, a friend of Gorey.

- THE GOREY DETAILS. BBC Radio program compiled and presented by Philip Glassborow, including interviews with Andreas Brown of the Gotham Book Mart, actor Frank Langella (star of Gorey's Dracula on Broadway), Alison Lurie, Alex Hand, Jack Braginton Smith, Katherine Kellgren and featuring David Suchet as the voice of Gorey.

- All The Gorey Details a May, 2003 article from The Independent by Philip Glassborow

[edit] External links

- Mystery! Edward Gorey interview from pbs.org

- Selected Gorey works from lunaea.com

- Works by or about Edward Gorey in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Elephant House: The Edward Gorey House contents photographed after his death by Kevin McDermott

- Edward Gorey Documentary Clips

- Edward Gorey Bibliography from fearofdolls.com

- Edwardian Ball website

- Edward Gorey showcase Gorey fan site

- Goreyography All about Gorey

|

||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Gorey, Edward St. John |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | writer, artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 22 or February 25, 1925 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chicago, Illinois |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 15, 2000 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | |