Polyphasic sleep

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Polyphasic sleep, a term coined by early 20th century psychologist J.S. Szymanski,[1] refers to the practice of sleeping multiple times in a 24-hour period—usually, more than two, in contrast to biphasic sleep —and does not imply any particular schedule. See also Segmented sleep and Sleep (Optimal amount). The term polyphasic sleep is also used by an online community which experiments with ultra-short napping to achieve more time awake each day.

Contents |

[edit] Multiphasic sleep of normal total duration

An example of polyphasic sleep is found in patients with irregular sleep-wake pattern, a circadian rhythm sleep disorder which usually is caused by head injury or dementia. Much more common examples are the sleep of human infants and of many animals. Elderly humans often have disturbed sleep, including polyphasic sleep.[2]

It has been noted that the Pirahã people generally sleep in smaller increments of time throughout the day, rarely sleeping for an entire night.[citation needed] This may provide evidence that the body's biological rhythms are indeed adaptable, and that the commonly accepted sleep pattern in most cultures is a culturally based, rather than biologically based, phenomenon.[citation needed]

In their 2006 paper “The Nature of Spontaneous Sleep Across Adulthood”, Campbell and Murphy studied sleep timing and quality in young, middle-aged and older adults. They found that, in freerunning conditions, the average duration of major nighttime sleep was significantly longer in young adults than in the other groups. The paper states further:

“Whether such patterns are simply a response to the relatively static experimental conditions, or whether they more accurately reflect the natural organization of the human sleep/wake system, compared with that which is exhibited in daily life, is open to debate. However, the comparative literature strongly suggests that shorter, polyphasically-placed sleep is the rule, rather than the exception, across the entire animal kingdom (Campbell and Tobler, 1984; Tobler, 1989). There is little reason to believe that the human sleep/wake system would evolve in a fundamentally different manner. That people often do not exhibit such sleep organization in daily life merely suggests that humans have the capacity (often with the aid of stimulants such as caffeine or increased physical activity) to overcome the propensity for sleep when it is desirable, or is required, to do so.” [3]

[edit] Napping in extreme situations

In crisis and other extreme conditions, people may not be able to achieve the recommended eight hours of sleep per day. Systematic napping may be considered necessary in such situations.

Dr. Claudio Stampi, as a result of his interest in long-distance solo boat racing, has studied the systematic timing of short naps as a means of ensuring optimal performance in situations where extreme sleep deprivation is inevitable, but he does not advocate ultrashort napping as a lifestyle.[4] Scientific American Frontiers (PBS) has reported on Stampi's 49-day experiment where a young man napped for a total of three hours per day. It purportedly shows that all stages of sleep were included.[5] Stampi has written about his research in his book "Why We Nap: Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep" (1992).[6] In 1989 he published results of a field study in the journal Work & Stress, concluding that "polyphasic sleep strategies improve prolonged sustained performance" under continuous work situations.[7]

[edit] The U.S. Military

The US military has studied fatigue countermeasures. An Air Force report states:

- "Each individual nap should be long enough to provide at least 45 continuous minutes of sleep, although longer naps (2 hours) are better. In general, the shorter each individual nap is, the more frequent the naps should be (the objective remains to acquire a daily total of 8 hours of sleep)."[8]

[edit] The Canadian Marine Pilots

Similarly, the Canadian Marine Pilots in their trainer's handbook report that:

- "[u]nder extreme circumstances where sleep cannot be achieved continuously, research on napping shows that 10- to 20-minute naps at regular intervals during the day can help relieve some of the sleep deprivation and thus maintain minimum levels of performance for several days. However, researchers caution that levels of performance achieved using ultrashort sleep (short naps) to temporarily replace normal sleep, are always well below that achieved when fully rested."[9]

[edit] NASA

NASA, in cooperation with the National Space Biomedical Research Institute, has funded research on napping. Despite NASA recommendations that astronauts sleep 8 hours a day when in space, they usually have trouble sleeping 8 hours at a stretch, so the agency needs to know about the optimal length, timing and effect of naps. Professor David Dinges of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine led research in a laboratory setting on sleep schedules which combined various amounts of "anchor sleep," ranging from about 4 to 8 hours in length, with no nap or daily naps of up to 2.5 hours. Longer naps were found to be better, with some cognitive functions benefiting more from napping than others. Vigilance and basic alertness benefited the least while working memory benefited greatly. Naps in the individual subjects' biological daytime worked well, but naps in their nighttime were followed by much greater sleep inertia lasting up to an hour.[10]

[edit] The Italian Air Force

The Italian Air Force (Aeronautica Militare Italiana) also conducted experiments for their pilots. In schedules involving night shifts and fragmentation of duty periods through the entire day, a sort of polyphasic sleeping schedule was studied. Subjects were to perform two hours of activity followed by four hours of rest (sleep allowed), this was repeated four times throughout the 24-hour day. Although sleep was allowed, subjects adopted a schedule of not sleeping at all during the first rest period of the day. The AMI published findings that "total sleep time was substantially reduced as compared to the usual 7-8 hour monophasic nocturnal sleep" while "maintaining good levels of vigilance as shown by the virtual absence of EEG microsleeps." EEG microsleeps are measurable and usually unnoticeable bursts of sleep in the brain while a subject appears to be awake. Nocturnal sleepers who sleep poorly may be heavily bombarded with microsleeps during waking hours, limiting focus and attention.[11]

[edit] Scheduled napping to achieve more 'wake-time'

People have tried to adopt a polyphasic schedule of short naps totalling about two to six hours per day, in order to gain more time awake in their day.

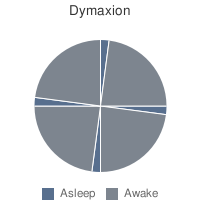

In an early mention of systematic napping as a lifestyle, Buckminster Fuller advocated his "Dymaxion Sleep," a regimen consisting of 30 minute naps every six hours, which he said he'd followed for two years. The short article about Fuller's sleep in TIME in 1943 also refers to such a schedule as "intermittent sleeping", and it notes:

- "Eventually he had to quit because his schedule conflicted with that of his business associates, who insisted on sleeping like other men."[12]

Critics consider the theory behind severe reduction of total sleep time by way of short naps unsound, claiming that there is no brain control mechanism that would make it possible to adapt to the "multiple naps" system. They say that the body will always tend to consolidate sleep into at least one solid block, and express concern that the ways in which the ultrashort nappers attempt to limit total sleep time, restrict time spent in the various stages of the sleep cycle, and disrupt the circadian rhythm of the body, will eventually cause them to suffer the same negative effects as those with other forms of sleep deprivation and circadian rhythm sleep disorders, such as decreased mental and physical ability, increased stress and anxiety, and a weakened immune system.[13]

Sara Mednick, Ph.D., whose sleep research investigates napping, included a chapter, Extreme Napping, in her book Take a Nap! Change Your Life.[14] In response to questions from readers about the "uberman" schedule, she wrote in May 2007:

- "This practice rests upon one important hypothesis that our biological rhythms are adaptable. This means that we can train our internal mechanisms not only when to sleep and wake, but also when to get hungry, have energy for exercise, perform mental activities. Inferred in this hypothesis is that we have the power to regulate our mood, metabolism, core body temperature, endocrine and stress response, basically everything inside this container of flesh we call home. Truly an Uberman feat!"[15]

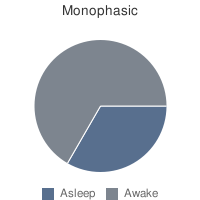

[edit] Comparison of sleep patterns

[edit] Bloggers

Starting in 1999, several people have experimented with alternative sleep patterns intended to reduce sleep time to 2–6 hours daily in order to have more time awake, and some of them have blogged their experiences. This is purportedly achieved by spreading out sleep into short naps of around 15–45 minutes throughout the day, and in some variants, a core sleep period of a few hours at night. The systematic napping patterns are, by the online proponents, called polyphasic sleep, and napping schedules include the Everyman sleep schedule and the Uberman sleep schedule.[16]

The blogger PureDoxyk, who coined the Uberman and Everyman names, wrote about her initial experimentation,[17] and then went on to write extensively about the Everyman sleep schedule and polyphasic sleep in general on her blog.[18] These efforts culminated in the 80-page book Ubersleep,[19] a comprehensive source about polyphasic sleeping.

According to reports by PureDoxyk and others, it takes roughly 7-14 days to convert to a polyphasic napping schedule. During the first few days, they claim, the body will experience controlled sleep deprivation and can be expected to enter REM and deep sleep stages more quickly during each nap. After the first week, some bloggers mention vivid dreams occurring during each[citation needed] nap and a refreshed feeling of wakefulness shortly after each nap.

Different sleep patterns may give individually varied results; the blogger Steve Pavlina reported difficulty switching from Uberman's sleep schedule, after five months, to Fuller's Dymaxion sleep schedule and gave up the attempt. WebMD's Dr. Breus ended his short series on Sleep Hackers by reporting Pavlina's return to monophasic sleep in 2006,[20] due to social problems caused by the unusual sleep schedule.[21]

Polyphasic sleeping blogs have become quite common and one can find blogs offering general information on polyphasic sleeping [22][23] as well as many offering personal accounts of their experiences. [24][25][26][27][28][29]

[edit] References

- ^ Danchin, Antoine. "Important dates 1900-1919". HKU-Pasteur Research Centre (Paris). http://www.pasteur.fr/recherche/unites/REG/causeries/dates_1900.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-12.

- ^ Mori, A. (January 1990). "Sleep disturbance in the elderly" (Abstract in English). Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi (Japan) 27 (1). PMID 2191161.

- ^ CAMPBELL S, MURPHY P. The nature of spontaneous sleep across adulthood. Journal of Sleep Research [serial on the Internet]. (2007, Mar), [cited November 6, 2008]; 16(1): 24-32. Available from: Academic Search Alumni Edition.

- ^ Wanjek, Christopher (2007-12-18). "Can You Cheat Sleep? Only in Your Dreams". LiveScience. http://www.livescience.com/health/071218-bad-sleep.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-11.

- ^ Alda, Alan (Show 105) (1991-02-27). "Catching catnaps (transcript)". PBS. http://www.pbs.org/saf/transcripts/transcript105.htm#5. Retrieved on 2008-02-19. "video"

- ^ Claudio Stampi. (1992) Why We Nap: Evolution, Chronobiology, and Functions of Polyphasic and Ultrashort Sleep. ISBN 0-8176-3462-2

- ^ Stampi, Dr. Claudio (January 1989). "Polyphasic sleep strategies improve prolonged sustained performance: A field study on 99 sailors". Work & Stress. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a782431473~db=all. Retrieved on 2008-06-02.

- ^ Caldwell, John A., Ph.D. (February 2003) (PDF, 24 pages). An Overview of the Utility of Stimulants as a Fatigue Countermeasure for Aviators. Brooks AFB, Texas: United States Air Force Research Laboratory. http://www.hep.afrl.af.mil/HEPF/Publications/TR/2003-0024.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-01-01. "(from Summary, page 19)".

- ^ Rhodes, Wayne, Ph.D., C.P.E.; Gil, Valérie, Ph.D. (last updated 2007-01-17) ([dead link] – Scholar search). Fatigue Management Guide for Canadian Marine Pilots – A Trainer's Handbook. Transport Canada, Transportation Development Centre. https://www.tc.gc.ca/tdc/publication/tp13960e/13960e.htm. Retrieved on 2008-01-01.

- ^ "NASA-supported sleep researchers are learning new and surprising things about naps". NASA. 3 June 2005. http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2005/03jun_naps.htm. Retrieved on 2008-02-19.

- ^ Porcú S, Casagrande M, Ferrara M, Bellatreccia A. SLEEP AND ALERTNESS DURING ALTERNATING MONOPHASIC AND POLYPHASIC REST-ACTIVITY CYCLES. International Journal of Neuroscience [serial on the Internet]. (1998, July), [cited November 6, 2008]; 95(1/2): 43. Available from: Academic Search Alumni Edition.

- ^ "Dymaxion Sleep". Time Magazine. 1943-10-11. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,774680,00.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-12.

- ^ Wozniak, Dr. Piotr (January 2005). Polyphasic Sleep: Facts and Myths. Super Memory (website). http://www.supermemo.com/articles/polyphasic.htm. Retrieved on 2008-01-01. "This article compares polyphasic sleep to regular monophasic sleep, biphasic sleep, as well as to the concept of free-running sleep".

- ^ Take a Nap! Change Your Life (Workman, 2006).

- ^ Mednick, Sara (11 May 2007). "Uberman, napping is all there is...". http://www.saramednick.com/blog/?p=15#more-15. Retrieved on 2008-03-23.; Archive link

- ^ PureDoxyk. "Charts of Types of Polyphasic Schedules". http://www.puredoxyk.com/index.php/about-polyphasic-sleep/charts-of-types-of-polyphasic-schedules/. Retrieved on 2009-02-28.

- ^ PureDoxyk (2000-12-29). "Uberman's Sleep Schedule". http://www.everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=892542. Retrieved on 2009-02-28.

- ^ PureDoxyk. "About Polyphasic Sleep". http://www.puredoxyk.com/index.php/about-polyphasic-sleep/. Retrieved on 2009-02-28.

- ^ The Ubersleep Book

- ^ Breus, Dr. Michael (19 April 2006). "Sleep Hacker Backs Off". WebMD. http://blogs.webmd.com/sleep-disorders/2006/04/sleep-hacker-backs-off.html. Retrieved on 2008-02-19.

- ^ Pavlina, Steve (12 April 2006). "Polyphasic Sleep: The Return to Monophasic". Steve Pavlina. http://www.stevepavlina.com/blog/2006/04/polyphasic-sleep-the-return-to-monophasic/. Retrieved on 2009-03-18.

- ^ Backpacker, The Polyphasic. http://thepolyphasicbackpacker.blogspot.com/. Blogger. [Online] November 19, 2008. [Cited: November 19, 2008.] http://thepolyphasicbackpacker.blogspot.com/.

- ^ Nori. Polyphasic Sleep Experiment: aka. Uberman sleep. Blogger. [Online] 2006. [Cited: November 19, 2008.] http://polyphasic.blogspot.com/.

- ^ Nishigaya, Andrew. Polyphasic Sleep Experiment: aka. Uberman sleep [Online] 2002. [Cited: November 30, 2008] http://polyphasic.blogspot.com/search?updated-min=2002-01-01T00%3A00%3A00-08%3A00&updated-max=2003-01-01T00%3A00%3A00-08%3A00&max-results=25

- ^ Jackie. My crazy polyphasic sleeper . Blogger. [Online] 2006. [Cited: November 19, 2008.] http://polyphasiccraziness.blogspot.com/2006_03_01_archive.html.

- ^ Jeremy. Polyphasic Sleeping in Ann Arbor . Blogger. [Online] 2006. [Cited: November 19, 2008.] http://polynappinginaa.blogspot.com/2006/06/day-72-been-while-since-i-posted-new.html.

- ^ Ekenstedt, Matthew. Polyphasic Sleep Experiment. [Online] 2006. [Cited: November 19, 2008.] http://polyphasic2.blogspot.com/search?updated-min=2006-01-01T00%3A00%3A00-08%3A00&updated-max=2007-01-01T00%3A00%3A00-08%3A00&max-results=25.

- ^ Jorel314 Adventures in Polyphasic Sleeping. [Online] 2008. [Cited: December 17, 2008.] http://polyphasic.dyndns.org/

- ^ Geekapolluza The Polyphasium. [Online] 2009. [Cited: February 25, 2009.] http://polyphasium.blogspot.com/

[edit] External links

- PolyphasicSleep.info - Informational wiki on intentional polyphasic sleep

- Miles to Go Before I Sleep at Outside.com, April 2005.

- Poly-phasers - an online polyphasic community

|

|||||||||||||||||