Hecate

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Hekate | |

The Hecate Chiaramonti, a Roman sculpture of triple Hecate, after a Hellenistic original (Museo Chiaramonti, Vatican Museums |

|

| Goddess of Witchcraft, Magic, Crossroads, Wilderness and Childbirth | |

| Parents | Perses and Asteria or Zeus and Hera |

|---|---|

| Children | Medea and Circe |

| Roman equivalent | Trivia |

Hecate (Greek: Ἑκάτη, "far-shooting"[1]) Hekate (Hekátê, Hekátē), or Hekat was a popular chthonian goddess attested early in Mycenaean Greece[2] or in Thrace, but possibly originating among the Carians of Anatolia,[3] the region where most theophoric names invoking Hecate, such as Hecataeus or Hecatomnus, progenitor of Mausollus, are attested,[4] and where Hecate remained a Great Goddess into historical times, at her unrivalled[5] cult site in Lagina. While many researchers favor the idea that she has Anatolian origins, it has been argued that "Hecate must have been a Greek goddess."[6] The monuments to Hecate in Phrygia and Caria are numerous but of late date.[7] The earliest inscription is found in late archaic Miletus, close to Caria, where Hecate is a protector of entrances.[8]

Regarding the nature of her cult, it has been remarked, "she is more at home on the fringes than in the centre of Greek polytheism. Intrinsically ambivalent and polymorphous, she straddles conventional boundaries and eludes definition."[9] She has been associated with childbirth, nurturing the young, gates and walls, doorways, crossroads, magic, lunar lore, torches and dogs. William Berg observes, "Since children are not called after spooks, it is safe to assume that Carian theophoric names involving hekat- refer to a major deity free from the dark and unsavoury ties to the underworld and to witchcraft associated with the Hecate of classical Athens."[10] But he cautions, "The Laginetan goddess may have had a more infernal character than scholars have been willing to assume."[11] In Ptolemaic Alexandria and elsewhere during the Hellenistic period, she appears as a three-faced goddess associated with ghosts, witchcraft, and curses. Today she is claimed as a goddess of witches and in the context of Hellenic Polytheistic Reconstructionism. Some neo-pagans refer to her as a "crone goddess"; although this characterization appears to conflict with her original virginal status in ancient Greece, both virgin and crone are often cast in myth as dangerous female beings because of their exclusion or freedom from the reproductive cycle.[12] She closely parallels the Roman goddess Trivia.

Contents |

[edit] Representations

The earliest Greek depictions of Hecate are single faced, not triplicate. Lewis Richard Farnell states:

- The evidence of the monuments as to the character and significance of Hekate is almost as full as that of the literature. But it is only in the later period that they come to express her manifold and mystic nature. Before the fifth century there is little doubt that she was usually represented as of single form like any other divinity, and it was thus that the Boeotian poet imagined her, as nothing in his verses contains any allusion to a triple formed goddess.

The earliest known monument is a small terracotta found in Athens, with a dedication to Hecate, in writing of the style of the sixth century. The goddess is seated on a throne with a chaplet bound round her head; she is altogether without attributes and character, and the only value of this work, which is evidently of quite a general type and gets a special reference and name merely from the inscription, is that it proves the single shape to be her earlier from, and her recognition at Athens to be earlier than the Persian invasion.[13]

The second-century traveller Pausanias stated that Hecate was first depicted in triplicate by the sculptor Alkamenes in the Greek Classical period of the late fifth century. Greek anthropomorphic conventions of art resisted representing her with three faces: a votive sculpture from Attica of the third century BCE (illustration, left), shows three single images against a column; round the column of Hecate dance the Charites. Some classical portrayals show her as a triplicate goddess holding a torch, a key, and a serpent. Others continue to depict her in singular form.

In Egyptian-inspired Greek esoteric writings connected with Hermes Trismegistus, and in magical papyri of Late Antiquity she is described as having three heads: one dog, one serpent, and one horse. Hecate's triplicity is elsewhere expressed in a more Hellenic fashion in the vast frieze of the great Pergamon Altar, now in Berlin, wherein she is shown with three bodies, taking part in the battle with the Titans. In the Argolid, near the shrine of the Dioscuri, Pausanias saw the temple of Hecate opposite the sanctuary of Eileithyia; He reported the image to be the work of Scopas, stating further, "This one is of stone, while the bronze images opposite, also of Hecate, were made respectively by Polycleitus and his brother Naucydes, son of Mothon." (Description of Greece ii.22.7)

A fourth century BCE marble relief from Crannon in Thessaly was dedicated by a race-horse owner.[14] It shows Hecate, with a hound beside her, placing a wreath on the head of a mare. She is commonly attended by a dog or dogs, and the most common form of offering was to leave meat at a crossroads. Sometimes dogs themselves were sacrificed to her. This is thought to be a good indication of her non-Hellenic origin, as dogs along with donkeys, very rarely played this role in genuine Greek ritual.[citation needed]

In Argonautica, a third century BCE Alexandrian epic based on early materials, Jason placates Hecate in a ritual prescribed by Medea, her priestess: bathed at midnight in a stream of flowing water, and dressed in dark robes, Jason is to dig a pit and offer a libation of honey and blood from the throat of a sheep, which was set on a pyre by the pit and wholly consumed as a holocaust, then retreat from the site without looking back (Argonautica, iii). All these elements betoken the rites owed to a chthonic deity.

[edit] Mythology

Hecate has been characterized as a pre-Olympian chthonic goddess. She appears in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter and in Hesiod's Theogony, where she is promoted strongly as a great goddess. The place of origin of her cult is uncertain, but it is thought that she had popular cult followings in Thrace.[3] Her most important sanctuary was Lagina, a theocratic city-state in which the goddess was served by eunuchs.[3] Lagina, where the famous temple of Hecate drew great festal assemblies every year, lay close to the originally Macedonian colony of Stratonikea, where she was the city's patroness.[15] In Thrace she played a role similar to that of lesser-Hermes, namely a governess of liminal regions (particularly gates) and the wilderness, bearing little resemblance to the night-walking crone she became. Additionally, this led to her role of aiding women in childbirth and the raising of young men.[citation needed]

Hesiod records that she was among the offspring of Gaia and Uranus, the Earth and Sky. In Theogony he ascribed great powers to Hecate:

[...] Hecate whom Zeus the son of Cronos honored above all. He gave her splendid gifts, to have a share of the earth and the unfruitful sea. She received honor also in starry heaven, and is honored exceedingly by the deathless gods. For to this day, whenever any one of men on earth offers rich sacrifices and prays for favor according to custom, he calls upon Hecate. Great honor comes full easily to him whose prayers the goddess receives favorably, and she bestows wealth upon him; for the power surely is with her. For as many as were born of Earth and Ocean amongst all these she has her due portion. The son of Cronos did her no wrong nor took anything away of all that was her portion among the former Titan gods: but she holds, as the division was at the first from the beginning, privilege both in earth, and in heaven, and in sea.[16]

According to Hesiod, she held sway over many things:

Whom she will she greatly aids and advances: she sits by worshipful kings in judgement, and in the assembly whom she will is distinguished among the people. And when men arm themselves for the battle that destroys men, then the goddess is at hand to give victory and grant glory readily to whom she will. Good is she also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents. And she is good to stand by horsemen, whom she will: and to those whose business is in the grey discomfortable sea, and who pray to Hecate and the loud-crashing Earth-Shaker, easily the glorious goddess gives great catch, and easily she takes it away as soon as seen, if so she will. She is good in the byre with Hermes to increase the stock. The droves of kine and wide herds of goats and flocks of fleecy sheep, if she will, she increases from a few, or makes many to be less. So, then, albeit her mother's only child, she is honored amongst all the deathless gods. And the son of Cronos made her a nurse of the young who after that day saw with their eyes the light of all-seeing Dawn. So from the beginning she is a nurse of the young, and these are her honors. [17]

Hesiod emphasizes that Hecate was an only child, the daughter of Perses and Asteria, a star-goddess who was the sister of Leto (the mother of Artemis and Apollo). Grandmother of the three cousins was Phoebe the ancient Titaness who personified the moon. Hecate was a reappearance of Phoebe[citation needed], a moon goddess herself, who appeared in the dark of the moon.

His inclusion and praise of Hecate in Theogony has been troublesome for scholars, in that he seems to hold her in high regard, while the testimony of other writers, and surviving evidence, suggests that this was probably somewhat exceptional. It is theorized that Hesiod’s original village had a substantial Hecate following and that his inclusion of her in the Theogony was a way of adding to her prestige by spreading word of her among his readers.[18]

If Hecate's cult spread from Anatolia into Greece, it is possible it presented a conflict, as her role was already filled by other more prominent deities in the Greek pantheon, above all by Artemis and Selene. This line of reasoning lies behind the widely accepted hypothesis that she was a foreign deity who was incorporated into the Greek pantheon. Other than in the Theogony, the Greek sources do not offer a consistent story of her parentage,[citation needed] or of her relations in the Greek pantheon: sometimes Hecate is related as a Titaness, and a mighty helper and protector of humans. Her continued presence was explained by asserting that, because she was the only Titan who aided Zeus in the battle of gods and Titans, she was not banished into the underworld realms after their defeat by the Olympians.[citation needed]

One surviving group of stories suggests how Hecate might have come to be incorporated into the Greek pantheon without affecting the privileged position of Artemis.[18] Here, Hecate is a mortal priestess often associated with Iphigeneia. She scorns and insults Artemis, who in retribution eventually brings about the mortal's suicide. Artemis then adorns the dead body with jewelry and commands the spirit to rise and become her Hecate, who subsequently performs a role similar to Nemesis as an avenging spirit, but solely for injured women. Such myths in which a native deity 'sponsors' or ‘creates’ a foreign one were widespread in ancient cultures as a way of integrating foreign cults. If this interpretation is correct, as Hecate’s cult grew, she was inserted into the later myth of the birth of Zeus as one of the midwives that hid the child,[18] while Cronus consumed the deceiving rock handed to him by Gaia. There was an area sacred to Hecate in the precincts of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, where the priests, megabyzi, officiated.[19]

Hecate also came to be associated with ghosts, infernal spirits, the dead and sorcery. Like the totems of Hermes—herms placed at borders as a ward against danger—images of Hecate (like Artemis and Diana, often referred to as a "liminal" goddess) were also placed at the gates of cities, and eventually domestic doorways. Over time, the association with keeping out evil spirits could have led to the belief that if offended, Hecate could also allow the evil spirits in. According to one view, this accounts for invocations to Hecate as the supreme governess of the borders between the normal world and the spirit world, and hence as one with mastery over spirits of the dead.[18] Whatever the reasons, Hecate’s power certainly came to be closely associated with sorcery. One interesting account exists asserting that the word "jinx" originated in a cult object associated with Hecate. "The Byzantine polymath Michael Psellus [...] speaks of a bullroarer, consisting of a golden sphere, decorated throughout with symbols and whirled on an oxhide thong. He adds that such an instrument is called a iunx (hence "jinx"), but as for the significance says only that it is ineffable and that the ritual is sacred to Hecate."[20]

Hecate is one of the most important figures in the so-called Chaldaean Oracles (2nd-3rd century CE)[21], where she is associated in fragment 194 with a strophalos (usually translated as a spinning top, or wheel, used in magic) "Labour thou around the Strophalos of Hecate."[22] This appears to refer to a variant of the device mentioned by Psellus.[23]

Variations in interpretations of Hecate's role or roles can be traced in fifth-century Athens. In two fragments of Aeschylus she appears as a great goddess. In Sophocles and Euripides she is characterized as the mistress of witchcraft and the Keres.

Implacable Hecate has been called "tender-hearted", a euphemism perhaps to emphasize her concern with the disappearance of Persephone, when she addressed Demeter with sweet words at a time when the goddess was distressed. She later became Persephone's minister and close companion in the Underworld. But Hecate was never fully incorporated among the Olympian deities.

The modern understanding of Hecate has been strongly influenced by syncretic Hellenistic interpretations. Many of the attributes she was assigned in this period appear to have an older basis. For example, in the magical papyri of Ptolemaic Egypt, she is called the 'she-dog' or 'bitch', and her presence is signified by the barking of dogs. In late imagery she also has two ghostly dogs as servants by her side. However, her association with dogs predates the conquests of Alexander the Great and the emergence of the Hellenistic world. When Philip II laid siege to Byzantium she had already been associated with dogs for some time; the light in the sky and the barking of dogs that warned the citizens of a night time attack, saving the city, were attributed to Hecate Lampadephoros (the tale is preserved in the Suda). In gratitude the Byzantines erected a statue in her honor.[24]

As with many ancient virgin goddesses she remained unmarried, had no regular consort, and often is said to have reproduced via parthenogenesis.[citation needed] In another aspect she is the mother of many monsters, such as Scylla, who represented the dreaded aspects of nature that elicited fear as well as awe.

[edit] Other names and epithets

- Chthonia (of the earth/underworld)[25]

- Enodia (on the way)[26]

- Kourotrophos (nurse of children)[27]

- Propulaia/Propylaia (before the gate)[28]

- Propolos (who serves/attends)[29]

- Phosphoros (bringing or giving light)[30]

- Soteira (savior)[31]

- Triodia/Trioditis (who frequents crossroads)[32]

- Klêidouchos (holding the keys)[33]

- Trimorphe (three-formed)[34]

[edit] Goddess of the crossroads

Cult images and altars of Hecate in her triplicate or trimorphic form were placed at crossroads (though they also appeared before private homes and in front of city gates).[35] In this form she came to be known as the goddess Trivia "the three ways" in Roman mythology. In what appears to be a 7th Century indication of the survival of cult practices of this general sort, Saint Eligius, in his Sermo warns the sick among his recently converted flock in Flanders against putting "devilish charms at springs or trees or crossroads",[36] and, according to Saint Ouen would urge them "No Christian should make or render any devotion to the deities of the trivium, where three roads meet...".[37]

[edit] Survival in pre-modern folklore

Hecate has survived in folklore as a 'hag' figure associated with witchcraft. Strmiska notes that Hecate, conflated with the figure of Diana, appears in late antiquity and in the early medieval period as part of an "emerging legend complex" associated with gatherings of women, the moon, and witchcraft that eventually became established "in the area of Northern Italy, southern Germany, and the western Balkans."[38] This theory of the Roman origins of many European folk traditions related to Diana or Hecate was explicitly advanced at least as early as 1807[39] and is reflected in numerous etymological claims by lexicographers from the 17th to the 19th century, deriving "hag" and/or "hex" from Hecate by way of haegtesse (Anglo-Saxon) and hagazussa (Old High German).[40] Such derivations are today proposed only by a minority[41] since being refuted by Grimm, who was skeptical of theories proposing non-Germanic origins for German folklore traditions.[42]

Whatever the precise nature of Hecate's transition into folklore in late Antiquity, she is now firmly established as a figure in Neopaganism, which draws heavily on folkloric traditions associating Hecate with 'The Wild Hunt', hedges and 'hedge-riding', and other themes that parallel, but are not explicitly attested in, Classical sources.

[edit] Animals

The bitch is the animal most commonly associated with Hecate. She was sometimes called the 'Black bitch'[citation needed] and black dogs were once sacrificed to her in purification rituals. At Colophon in Thrace, Hecate might be manifest as a dog. The sound of barking dogs was the first sign of her approach in Greek and Roman literature. Hecate is also sometimes associated with deer as is her counterpart Diana, goddess of the hunt.

The frog, significantly a creature that can cross between two elements, also is sacred to Hecate.[43]

As a triple goddess, she sometimes appears with three heads-one each of a dog, horse, and bear or of dog, serpent, and lion.

It was asserted in Malleus Maleficarum (1486) that Hecate was revered by witches who adopted parts of her mythos as their goddess of sorcery. Because Hecate had already been much maligned by the late Roman period, Christians found it easy to vilify her image. Thus were all her creatures also considered "creatures of darkness"; however, the history of creatures such as ravens, night-owls, snakes, scorpions, asses, bats, horses, bears, and lions as her creatures is not always a dark and frightening one. (Rabinovich 1990)

[edit] Plants and herbs

The yew, cypress[44], hazel, black poplar, cedar, and willow are all sacred to Hecate[citation needed].

The leaves of the black poplar are dark on one side and light on the other, symbolizing the boundary between the worlds. The yew has long been associated with the Underworld.[citation needed]

The yew has strong associations with death as well as rebirth. A poison prepared from the seeds was used on arrows[citation needed], and yew wood was commonly used to make bows and dagger hilts. The potion in Hecate's cauldron contains 'slips of yew'. Yew berries carry Hecate's power, and can bring wisdom or death. The seeds are highly poisonous, but the fleshy, coral-colored 'berry' surrounding it is not.

Many other herbs and plants are associated with Hecate, including garlic, almonds, lavender, thyme, myrrh, mugwort, cardamon, mint, dandelion, hellebore, yarrow and lesser celandine. Several poisons and hallucinogens are linked to Hecate, including belladonna, hemlock, mandrake, aconite (known as hecateis), and the opium poppy. Many of Hecate's plants were those that can be used shamanistically to achieve varyings states of consciousness.

[edit] Places

Wild areas, forests, borders, city walls and doorways, crossroads, and graveyards are all associated with Hecate at various times.

It is often stated that the moon is sacred to Hecate. This is argued against by Farnell (1896, p.4):

- Some of the late writers on mythology, such as Cornutus and Cleomedes, and some of the modern, such as Preller and the writer in Roscher's Lexicon and Petersen, explain the three figures as symbols of the three phases of the moon. But very little can be said in favour of this, and very much against it. In the first place, the statue of Alcamenes represented Hekate Επιπυργιδια, whom the Athenian of that period regarded as the warder of the gate of his Acropolis, and as associated in this particular spot with the Charites, deities of the life that blossoms and yields fruit. Neither in this place nor before the door of the citizen's house did she appear as a lunar goddess.

- We may also ask, why should a divinity who was sometimes regarded as the moon, but had many other and even more important connexions, be given three forms to mark the three phases of the moon, and why should Greek sculpture have been in this solitary instance guilty of a frigid astronomical symbolism, while Selene, who was obviously the moon and nothing else, was never treated in this way? With as much taste and propriety Helios might have been given twelve heads.

However in the magical papyri of Greco-Roman Egypt[45] there survive several hymns which identify Hecate with Selene and the moon, extolling her as supreme Goddess, mother of the gods. In this form, as a threefold goddess, Hecate continues to have followers in some neopagan religions.[46]

[edit] Festivals

Hecate was worshipped by both the Greeks and the Romans who had their own festivals dedicated to her. According to Ruickbie (2004:19) the Greeks observed two days sacred to Hecate, one on the 13th of August and one on the 30th of November, whilst the Romans observed the 29th of every month as her sacred day.

[edit] Cross-cultural parallels

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2008) |

The figure of Hecate can often be associated with the figure of Isis in Egyptian myth, mainly due to her role as sorceress.[citations needed] Both were symbols of liminal points. Lucius Apuleius (c. 123 - c. 170 CE) in his work "The Golden Ass" associates Hecate with Isis:

'I am she that is the natural mother of all things, mistress and governess of all the elements, the initial progeny of worlds, chief of powers divine, Queen of heaven, the principal of the Gods celestial, the light of the goddesses: at my will the planets of the air, the wholesome winds of the Seas, and the silences of hell be disposed; my name, my divinity is adored throughout all the world in divers manners, in variable customs and in many names, [...] Some call me Juno, others Bellona of the Battles, and still others Hecate. Principally the Ethiopians which dwell in the Orient, and the Egyptians which are excellent in all kind of ancient doctrine, and by their proper ceremonies accustomed to worship me, do call me Queen Isis.[...]'[47]

Some historians ultimately compare her to the Virgin Mary. She is also comparable to Hel of Nordic myth in her underworld function.[citations needed]

Before she became associated with Greek mythology, she had many similarities with Artemis (wilderness, and watching over wedding ceremonies)[48] and Hera (child rearing and the protection of young men or heroes, and watching over wedding ceremonies).[citations needed]

[edit] Hecate in literature

Hecate is a character in William Shakespeare's tragedy Macbeth, which was first performed circa 1605; she commands the Three Witches, although whether she is a witch, a demon or a goddess is not known. There is some evidence to suggest that the character and the scenes or portions thereof in which she appears (Act III, Scene v, and a portion of Act IV, Scene i) were not written by Shakespeare, but were added during a revision by Thomas Middleton,[49] who used material from his own play The Witch, which was produced in 1615. Most modern texts of Macbeth indicate the interpolations.

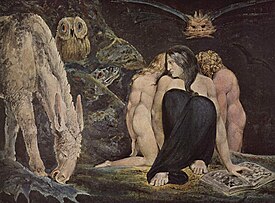

William Blake portrayed Hecate in a number of his paintings and poems.

[edit] In popular culture

- Hecate figures in the novel The Alchemyst: The Secrets of the Immortal Nicholas Flamel.

- In Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Hecate is often invoked by witches such as Willow Rosenberg and particularly Amy Madison during their spells.

- In the first season of Charmed Hecate is the Queen of the Underworld who comes to earth every 200 years to find an innocent man and put him under her spell so she can create a demonic spawn.

- Hecate appears in the Hellboy comic series as one of its principal antagonists, the serpentine Queen of Witches.

- In the anime series Shakugan no Shana, Hecate is the name of the supreme leader of Bal Masqué. Her exact title is Itadaki no Kura (literally: Supreme Throne).

- Breakcore artist Rachel Kozak performs as Hecate.

- There is a Symphonic black metal band named Hecate Enthroned

- Hecate is the 5th level of the Succubus, a creatable monster character class in the Disgaea games.

- Hecate is a class of destroyer in FreeSpace 2.

- In Sandra Heath's regency romance novel Halloween Magic, Hecate appears as the goddess of witchcraft and evil, whom Judith Villiers worships. Judith summons Hecate's face in a stone called the Lady in order to perform her magic.

- J.N. Williamson has written a well researched horror novel/social satire Queen of Hell (1981) wherein a prophecy is fulfilled as Hecate is born in human form. She comes to self-awareness in the person of a California college girl.

- One of the titans in the Dune series during the Butlerian Jihad uses the name Hecate.

- Hecate appears twice in Hercules: The Animated Series as the evil witch who attempts to take over the Underworld from the god Hades. She is in the episodes The Underworld Takeover and the Disappearing Heroes. She is voiced by Peri Gilpin

- Hecate appears as one of the villains in Class of the Titans in the episode See You at the Crossroads.

- In the Warhammer mythos the Dark Elves venerate a many-armed goddess of black sorcery called Hekarti, one of the chthonic elven deities known as the Cytharai. The ruler of this pantheon, the Dark Mother Ereth-Khiyal, also bears some similarities to the classical Hecate.

- In the pilot of the proposed DrWho spin-off series K-9 and Company, the local witch coven, who attempt human sacrifice during the episode, worship Hecate.

- In the comic book prequel of The Dresden Files, Harry is forced to fight against a trio of "Hecatean hags" who are using animal blood to make themselves more powerful. Bob the Skull indicates that Hecate herself was once one of them, and the ritual allowed her to become a goddess.

- In the 1981 TV-Movie Midnight Offerings, the main witch, Vivian Sotherland, worships Hecate at a dark altar

- In the anime series The Melody of Oblivion, Hecate holds court in an underground bowling alley. It is implied that the souls of those sacrificed to her become her bowling balls.

- Hecatae is in many Book of Shadows in TV series and demon books, such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Charmed, and Supernatural.

- In the popular Night World series, by author L. J. Smith Hecate is the original witch, from whom all other witches are descended.

[edit] Notes

- ^ The most common, and most widely accepted proposed etymology for the name Hecate derives it from the Greek Ἑκάτη, "the feminine equivalent of Hekatos, an obscure epithet of Apollo" (Hornblower, Spawforth (Eds.) The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 1996, p671) This has been variously translated as "far shooting", "far darter" or "her that operates from afar". An alternative interpretation derives it (at least in the case of Hesiod's use) from the Greek word for will, which leads one researcher to identify "the name and function of Hecate as the one by whose will prayers are accomplished and fulfilled." (Jenny Strauss Clay, Hesiod's Cosmos, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p135). Clay lists a number of researchers who have advanced some variant of the association between Hecate's name and will (e.g. Walcot (1958), Neitzel (1975), Derossi (1975)). This interpretation also appears in Liddell-Scott, A Greek English Lexicon in the entry for Hecate, which is glossed as "lit. she who works her will".

- ^ William Berg, "Hecate: Greek or 'Anatolian'?", Numen 21.2 (August 1974:128-40).

- ^ a b c Walter Burkert, (1987) Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, pp 171. Oxford, Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-15624-0.

- ^ Theodor Kraus, Hekate: Studien zu Wesen u. Bilde der Göttin in Kleinasien u. Griechenland (Heidelberg) 1960. Kraus offers the first modern comprehensive discussion of Hecate in monuments and material culture.

- ^ Berg 1974:128: Berg remarks of Hecate's endorsement of Roman hegemony in her representation on the pediment at Lagina solemnising a pact between a warrior (Rome) and an amazon (Asia)

- ^ Berg 1974:134. Berg's argument for a Greek origin rests on three main points: 1. Almost all archaeological and literary evidence for her cult comes from the Greek mainland, and especially from Attica - all of which dates earlier than the 2nd century BCE. 2. In Asia Minor only one monument can be associated with Hecate prior to the 2nd century BCE. 3. The supposed connection between Hecate and attested "Carian theophoric names" is not convincing, and instead suggests an aspect of the process of her Hellenization. He concludes, "Arguments for Hecate's "Anatolian" origin are not in accord with evidence."

- ^ Kraus 1960:52; list p 166f.

- ^ Kraus 1960:12.

- ^ Hornblower, Spawforth (Eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary, Third Edition, Oxford University Press, 1996, p671

- ^ Berg 1974:129.

- ^ Berg 1974:137.

- ^ For background on the relation of virgin and crone in the context of female "demons" and reproduction, see Karen Hartnup, On the Beliefs of the Greeks (Brill, 2004), p. 150 online.

- ^ Lewis Richard Farnell, (1896). "Hecate in Art," The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ This statue is in the British Museum, inventory number 816.

- ^ Strabo, Geography xiv.2.25; Kraus 1960.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, (English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White)

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, (English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White)

- ^ a b c d Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1991). Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. ISBN 0-520-21707-1

- ^ Strabo, Geography, xiv.1.23

- ^ Mark Edwards, Neoplatonic saints: the Lives of Plotinus and Proclus by their Students, Liverpool University Press, 2000, p100

- ^ The Chaldaean Oracles are a group of oracles (possibly oracular pronouncements made by priests of a number of gods) that date from somewhere between the 2nd century and the late 3rd century, the recording of which is traditionally attributed to one Julian the Chaldaean or his son, Julian the Theurgist. The most important of these deities was apparently Hecate. The material seems to have provided background and explanation related to the meaning of these pronouncements, and appear to have been related to the practice of theurgy, pagan magic that later became closely associated with Neoplatonism (source: Hornblower, Spawforth, The Oxford Classical Dictionary, 1996, p316).

- ^ English translation used here from: William Wynn Wescott (tr.), The Chaldaean Oracles of Zoroaster, 1895

- ^ "A top of Hekate is a golden sphere enclosing a lapis lazuli in its middle that is twisted through a cow-hide leather thong and having engraved letters all over it. [Diviners] spin this sphere and make invocations. Such things they call charms, whether it is the matter of a spherical object, or a triangular one, or some other shape. While spinning them, they call out unintelligible or beast-like sounds, laughing and flailing at the air. [Hekate] teaches the taketes to operate, that is the movement of the top, as if it had an ineffable power. It is called the top of Hekate because it is dedicated to her. For Hekate was a goddess among the Chaldaeans. In her right hand she held the source of the virtues. But it is all nonsense." As quoted in Frank R. Trombley, Hellenic Religion and Christianization, C. 370-529, BRILL, 1993, p319

- ^ "In 340 B.C., however, the Byzantines, with the aid of the Athenians, withstood a siege successfully, an occurrence the more remarkable as they were attacked by the greatest general of the age, Philip of Macedon. In the course of this beleaguerment, it is related, on a certain wet and moonless night the enemy attempted a surprise, but were foiled by reason of a bright light which, appearing suddenly in the heavens, startled all the dogs in the town and thus roused the garrison to a sense of their danger. To commemorate this timely phenomenon, which was attributed to Hecate, they erected a public statue to that goddess [...]" William Gordon Holmes, The Age of Justinian and Theodora, 2003 p5-6; "If any goddess had a connection with the walls in Constantinople, it was Hecate. Hecate had a cult in Byzantium from the time of its founding. Like Byzas in one legend, she had her origins in Thrace. Since Hecate was the guardian of "liminal places," in Byzantium small temples in her honor were placed close to the gates of the city. Hecate's importance to Byzantium was above all as deity of protection. When Philip of Macedon was about to attack the city, according to he legend she alerted the townspeople with her ever-present torches, and with her pack of dogs, which served as her constant companions. Her mythic qualities thenceforth forever entered the fabric of Byzantine history. A statue known as the 'Lampadephoros' was erected on the hill above the Bosphorous to commemorate Hecate's defensive aid." Vasiliki Limberis, Divine Heiress, Routledge, 1994, p126-127; this story apparently survived in the works Hesychius of Miletus, who in all probability lived in the time of Justinian. His works survive only in fragments preserved in Photius and the tenth century lexicographer Suidas. The tale is also related by Stephanus of Byzantium, and Eustathius.

- ^ Jon D. Mikalson, Athenian Popular Religion, UNC Press, 1987, p76

- ^ Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 1999, pp 208-209

- ^ Liddell, Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Sarah Iles Johnston, Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece, University of California Press, 1999, p207

- ^ Liddell, Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Liddell, Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Sarah Iles Johnston, Hekate Soteira, Scholars Press, 1990

- ^ Liddell, Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Liddell, Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Liddell, Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Hornblower, Spawforth, Oxford Classical Dictionary, 3rd Edition, 1996, p671

- ^ Amanda Porterfield, Healing in the history of Christianity, Oxford University Press, 2005, p72

- ^ Saint Ouen, Vita Eligii book II.16.

- ^ Michael Strmiska, Modern paganism in world cultures, ABC-CLIO, 2005, p68

- ^ Francis Douce, Illustrations of Shakspeare, and of Ancient Manners, 1807 p235-243

- ^ Minsheu and Somner (17th century), Edward Lye of Oxford (1694-1767), Johann Georg Wachter, Glossarium Germanicum (1737), Walter Whiter, Etymologicon Universale (1822)

- ^ e.g. Gerald Milnes, Signs, Cures, & Witchery, Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2007, p116; Samuel X. Radbill, "The Role of Animals in Infant Feeding", in American Folk Medicine: A Symposium Ed. Wayland D. Hand. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976

- ^ "Many have been caught by the obvious resemblance of the Gr. Hecate, but the letters agree to closely, contrary to the laws of change, and the Mid. Ages would surely have had an unaspirated Ecate handed down to them; no Ecate or Hecate appears in the M. Lat. or Romance writings in the sense of witch, and how should the word have spread through all German lands?" Jacob Grimm, Teutonic Mythlogy, 1835, (English translation 1900)

- ^ Varner, Gary R. (2007). Creatures in the Mist: Little People, Wild Men and Spirit Beings Around the World: A Study in Comparative Mythology, p. 135. New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 0875865461.

- ^ Freize, Henry; Dennison, Walter (1902). Virgil's Aeneid. New York: American Book Company. pp. N111.

- ^ Betz, Hans Dieter (ed.) (1989). The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation : Including the Demotic Spells : Texts. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Pike, Sarah M. (2004). New Age and Neopagan Religions in America, pp. 131-32. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231124023.

- ^ Lucius Apuleius, (c.155 CE) The Golden Ass Book 11, Chap 47.

- ^ Heidel, William Arthur (1929). The Day of Yahweh: A Study of Sacred Days and Ritual Forms in the Ancient Near East, p. 514. American Historical Association.

- ^ Taylor, Gary, and Lavagnino, John (eds.) (2007) Thomas Middleton and Early Modern Textual Culture, pp. 384-85. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198185707.

[edit] References

[edit] Primary sources

- Hesiod, Theogony, Works and Days. An English translation is available online

- Pausanias, Description of Greece

- Strabo, Geography

[edit] Secondary sources

- Burkert, Walter, 1985. Greek Religion (Cambridge: Harvard University Press) Published in the UK as Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, 1987. (Oxford: Blackwell) ISBN 0-631-15624-0.

- Lewis Richard Farnell, (1896). "Hecate in Art", The Cults of the Greek States. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1990). Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate's Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles, (1991). Restless Dead: Encounters Between the Living and the Dead in Ancient Greece. ISBN 0-520-21707-1

- Mallarmé, Stephane, (1880). Les Dieux Antiques, nouvelle mythologie illustrée.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. Hekate Soteira: A Study of Hekate's Role in the Chaldean Oracles and Related Literature. 1990.

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. 1951.

- Rabinovich,Yakov. The Rotting Goddess. 1990. A work which views Hekate from the perspective of Mircea Eliade's archetypes and substantiates its claims through cross-cultural comparisons. The work has been sharply criticized by Classics scholars, some dismissing Rabinowitz as a neo-pagan.

- Ruickbie, Leo. Witchcraft Out of the Shadows: A Complete History. Robert Hale, 2004.

- Turner, J. D. "The Figure of Hecate and Dynamic Emanationism in The Chaldaean Oracles, Sethian Gnosticism and Neoplatonism," The Second Century Journal 7:4, (1991), 221-232.

- Berg, William, "Hecate: Greek or "Anatolian"?", Numen 21.2 (August 1974:128-40)

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Hecate |

- Myths of the Greek Goddess Hecate

- Frequently Asked Questions about Hekate

- Encyclopaedia Britanica 1911: "Hecate"

- Hekate: Guardian at the Gate

- The Rotting Goddess by Yakov Rabinovich, complete book included in the anthology "Junkyard of the Classics" published under the pseudonym Ellipsis Marx.

- Theoi Project, Hecate Classical literary sources and art

- Hecate in Early Greek Religion

- Hekate in Greek esotericism: Ptolemaic and Gnostic transformations of Hecate

- Cast of the Crannon statue, at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.