Sufism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sufism (Arabic: تصوّف - taṣawwuf, Persian: صوفیگری sufigari, Turkish: tasavvuf, Urdu: تصوف) is generally understood to be the inner, mystical dimension of Islam.[1][2][3] A practitioner of this tradition is generally known as a ṣūfī (صُوفِيّ), though some adherents of the tradition reserve this term only for those practitioners who have attained the goals of the Sufi tradition. Another name used for the Sufi seeker is dervish.

Classical Sufi scholars have defined Sufism as "a science whose objective is the reparation of the heart and turning it away from all else but God."[4] Alternatively, in the words of the renowned Darqawi Sufi teacher Ahmad ibn Ajiba, "a science through which one can know how to travel into the presence of the Divine, purify one’s inner self from filth, and beautify it with a variety of praiseworthy traits."[5]

The Sufi movement has spanned several continents and cultures over a millennium, at first expressed through Arabic, then through Persian, Turkish, and a dozen other languages.[6] Sufi orders, which are either Shi'a or Sunni in doctrine, trace their origins from the Prophet of Islam, Muhammad, through his cousin Ali, or from Abu Bakr. Despite sufi tradition long being rooted in Muslim culture and tradition, there are some factions of Islam — especially Salafism and Wahhabism — that consider Sufism heretical.

According to some modern proponents, such as Idries Shah, the Sufi philosophy is universal in nature, its roots predating the arising of Islam and the other modern-day religions; likewise, some Muslims feel that Sufism is outside the sphere of Islam.[7][8][1]

Contents |

[edit] Etymology

The lexical root of Sufi is variously traced to صوف ṣūf "wool", referring either to the simple cloaks the early Muslim ascetics wore, or possibly to صفا ṣafā "purity". The two were combined by al-Rudhabari who said, "The Sufi is the one who wears wool on top of purity."[9]

Others suggest the origin of the word ṣufi is from Aṣhab aṣ-ṣuffa "Companions of the Porch", who were a group of impoverished Muslims during the time of Muhammad who spent much of their time on the veranda of the Prophet's mosque, devoted to prayer and eager to memorize each new increment of the Qur'ān as it was revealed. Yet another etymology, advanced by the 10th century Persian historian Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī is that the word is linked with Greek word sophia "wisdom".

[edit] Basic views

While all Muslims believe that they are on the pathway to God and will become close to God in Paradise — after death and after the "Final Judgment" — Sufis also believe that it is possible to draw closer to God and to more fully embrace the Divine Presence in this life.[10] The chief aim of all Sufis is to seek the pleasing of God by working to restore within themselves the primordial state of fitra,[11] described in the Qur'an and similar to the concept of Buddha nature. In this state nothing one does defies God, and all is undertaken by the single motivation of love of God. A secondary consequence of this is that the seeker may be led to abandon all notions of dualism or multiplicity, including a conception of an individual self, and to realize the Divine Unity.

Thus Sufism has been characterized as the science of the states of the lower self (the ego), and the way of purifying this lower self of its reprehensible traits, while adorning it instead with what is praiseworthy, whether or not this process of cleansing and purifying the heart is in time rewarded by esoteric knowledge of God. This can be conceived in terms of two basic types of law (fiqh), an outer law concerned with actions, and an inner law concerned with the human heart. The outer law consists of rules pertaining to worship, transactions, marriage, judicial rulings, and criminal law — what is often referred to, a bit too broadly, as shariah. The inner law of Sufism consists of rules about repentance from sin, the purging of contemptible qualities and evil traits of character, and adornment with virtues and good character.[12]

To enter the way of Sufism, the seeker begins by finding a teacher, as the connection to the teacher is considered necessary for the growth of the pupil. The teacher, to be genuine, must have received the authorization to teach (ijazah) of another Master of the Way, in an unbroken succession (silsilah) leading back to Sufism's origin with the Prophet Muhammad. It is the transmission of the divine light from the teacher's heart to the heart of the student, rather than of worldly knowledge transmitted from mouth to ear, that allows the adept to progress. In addition, the genuine teacher will be utterly strict in his adherence to the Divine Law.[13]

Scholars and adherents of Sufism are unanimous in agreeing that Sufism cannot be learned through books. To reach the highest levels of success in Sufism typically requires that the disciple live with and serve the teacher for many, many years. For instance, Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari, considered founder of the Naqshbandi Order, served his first teacher, Sayyid Muhammad Baba As-Samasi, for 20 years, until as-Samasi died. He subsequently served several other teachers for lengthy periods of time. The extreme arduousness of his spiritual preparation is illustrated by his service, as directed by his teacher, to the weak and needy members of his community in a state of complete humility and tolerance for many years. When he believed this mission to be concluded, his teacher next directed him to care for animals, curing their sicknesses, cleaning their wounds, and assisting them in finding provision. After many years of this he was next instructed to spend many years in the care of dogs in a state of humility, and to ask them for support.[14]

As a further example, the prospective adherent of the Mevlevi Order would have been ordered to serve in the kitchens of a hospice for the poor for 1,001 days prior to being accepted for spiritual instruction, and a further 1,001 days in solitary retreat as a precondition of completing that instruction.[15]

Some teachers, especially when addressing more general audiences, or mixed groups of Muslims and non-Muslims, make extensive use of parable, allegory, and metaphor.[16] Although approaches to teaching vary among different Sufi orders, Sufism as a whole is primarily concerned with direct personal experience, and as such has sometimes been compared to other, non-Islamic forms of mysticism (e.g., as in the books of Seyyed Hossein Nasr).

Sufism, which is a general term for Muslim mysticism, sprang up largely in reaction against the worldliness which infected Islam when its leaders became the powerful and wealthy rulers of multitudes of people and were influenced by foreign cultures. Harun al-Rashid, eating off gold and silver, toying with a harem of scented beauties, surrounded by an impenetrable retinue of officials, eunuchs and slaves, was a far cry from the stern simplicity of an Umar, who lived in the modest house, wore patched clothes and could be approached by any of his followers. [17]

The typical early Sufi lived in a cell of in a mosque and taught a small band of disciples. The extent to which Sufism was influenced by Buddhist and Hindu mysticism, and by the example Christian hermits and monks, is disputed, but self-discipline and concentration on God quickly led to the belief that by quelling the self and through loving ardour for God it was possible to maintain a union with the divine in which the human self melted away. [17]

[edit] History of Sufism

[edit] Origins

In its early stages of development Sufism effectively referred to nothing more than the internalization of Islam.[18] According to one perspective, it is directly from the Qur’an, constantly recited, meditated, and experienced, that Sufism proceeded, in its origin and its development.[19] Others have held that Sufism is the strict emulation of the way of Muhammad, through which the heart's connection to the Divine is strengthened.[20]

From the traditional Sufi point of view, the esoteric teachings of Sufism were transmitted from the Prophet Muhammad to those who had the capacity to acquire the direct experiential gnosis of God, which was passed on from teacher to student through the centuries. Some of this transmission is summarized in texts, but most is not. Important contributions in writing are attributed to Uwais al-Qarni, Harrm bin Hian, Hasan Basri and Sayid ibn al-Mussib, who are regarded as the first Sufis in the earliest generations of Islam. Harith al-Muhasibi was the first one to write about moral psychology. Rabia Basri was a Sufi known for her love and passion for God, expressed through her poetry. Bayazid Bastami was among the first theorists of Sufism; he concerned himself with fanā and baqā, the state of annihilating the self in the presence of the divine, accompanied by clarity concerning worldly phenomena derived from that perspective.[21]

Sufism had a long history already before the subsequent institutionalization of Sufi teachings into devotional orders (tarîqât) in the early Middle Ages.[22] Almost all extant Sufi orders trace their chains of transmission (silsila) back to Prophet Muhammad via his cousin and son-in-law Ali. The Naqshbandi order is a notable exception to this rule, as it traces the origin of its teachings from the Prophet Muhammad to the first Islamic Caliph Abu Bakr.

Different devotional styles and traditions developed over time, reflecting the perspectives of different masters and the accumulated cultural wisdom of the orders. Typically all of these concerned themselves with the understanding of subtle knowledge (gnosis), education of the heart to purify it of baser instincts, the love of God, and approaching God through a well-described hierarchy of enduring spiritual stations (maqâmât) and more transient spiritual states (ahwâl).

[edit] Formalization of doctrine

Towards the end of the first millennium CE, a number of manuals began to be written summarizing the doctrines of Sufism and describing some typical Sufi practices. Two of the most famous of these are now available in English translation: the Kashf al-Mahjûb of Hujwiri, and the Risâla of Qushayri.[23]

Two of Imam Al Ghazali's greatest treatises, the "Revival of Religious Sciences" and the "Alchemy of Happiness," argued that Sufism originated from the Qur'an and was thus compatible with mainstream Islamic thought, and did not in any way contradict Islamic Law — being instead necessary to its complete fulfillment. This became the mainstream position among Islamic scholars for centuries, challenged only recently on the basis of selective use of a limited body of texts. Ongoing efforts by both traditionally-trained Muslim scholars and Western academics are making Imam Al-Ghazali's works available in English translation for the first time,[24] allowing readers to judge for themselves the compatibility between Islamic Law and Sufi doctrine.

These remarks concern written sources. It is to be remembered that Sufism is transmitted from the heart of the teacher to the heart of the student, not through texts; and also, that texts may not convey everything, or may be read by different seekers on different levels. Therefore the notion of a "formalization of doctrine" in Sufism is not strictly correct.

[edit] Growth of Sufi influence in Islamic cultures

The spread of Sufism has been considered a definitive factor in the spread of Islam, and in the creation of integrally Islamic cultures, especially in Africa[25] and Asia. Recent academic work on these topics has focused on the role of Sufism in creating and propagating the culture of the Ottoman world,[26] and in resisting European imperialism in Africa and South Asia.[27]

Between the 13th and 16th centuries CE, Sufism produced a flourishing intellectual culture throughout the Islamic world, a sort of "Golden Age" whose physical artifacts are still present. In many places, a lodge (known variously as a zaouia, khanqah, or tekke) would be endowed through a pious foundation in perpetuity (waqf) to provide a gathering place for Sufi adepts, as well as lodging for itinerant seekers of knowledge. The same system of endowments could also be used to pay for a complex of buildings, such as that surrounding the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul, including a lodge for Sufi seekers, a hospice with kitchens where these seekers could serve the poor and/or complete a period of initiation, a library, and other structures. No important domain in the civilization of Islam remained unaffected by Sufism in this period.[28]

[edit] Contemporary Sufism

Sufism suffered many setbacks in the modern era, particularly (though not exclusively) at the hands of European imperialists in the colonized nations of Asia and Africa. The life of the Algerian Sufi master Emir Abd al-Qadir is instructive in this regard.[29] Notable as well are the lives of Amadou Bamba and Hajj Umar Tall in sub-Saharan Africa, and Sheikh Mansur Ushurma and Imam Shamil in the Caucasus region.

Sufism being the central organizing principle of many traditional Islam cultures, it is not surprising that colonial powers attacked Sufi masters as one means of undermining the forces of indigenous self-determination.

In spite of this recent history of official repression, there remain many places in the world with vital Sufi traditions. Sufism is popular in such African countries as Senegal, where it is seen as a mystical expression of Islam.[30] Mbacke suggests that one reason Sufism has taken hold in Senegal is because it can accommodate local beliefs and customs, which tend toward the mystical.[31]

In South Asia, four major Sufi orders persist, namely the Chishti Order, the Qadiriyyah, the Naqshbandiyya, and the Suhrawardiyya. The Deobandis (i.e., adherents of the Darul Uloom Deoband) and Barelwi are two significant Islamic movements in this region whose followers often belong to one of these orders.[32]

For a more complete summary of currently active groups and teachers, readers are referred to links in the site of Dr. Alan Godlas of the University of Georgia.[33][34]

A number of Westerners have embarked with varying degrees of success on the path of Sufism. One of the first to return to Europe as an official representative of a Sufi path, and with the specific purpose to spread Sufism in Western Europe, was the Swedish-born wandering Sufi Abd al-Hadi Aqhili. The ideas propagated by such spiritualists may or may not conform to the tenets of Sufism as understood by orthodox Muslims, as for instance with G. I. Gurdjieff and Shawni. On the other hand, American- and British-born teachers such as Nuh Ha Mim Keller, Hamza Yusuf, and Abdal Hakim Murad have been instrumental in spreading messages that conform fully with the normative tenets of Islam.

Other noteworthy Sufi teachers who have been active in the West in recent years include Nader Angha, Hazrat Inayat Khan, Riaz Ahmed Gohar Shahi, Muhammad Emin Er, Nazim al-Qubrusi, Javad Nurbakhsh, and Muzaffer Ozak.

[edit] Theoretical perspectives in Sufism

Traditional Islamic scholars have recognized two major branches within the practice of Sufism, and use this as one key to differentiating among the approaches of different masters and devotional lineages.[35]

On the one hand there is the path from the signs to the Signifier (or from the arts to the Artisan). In this branch, the seeker begins by purifying the lower self of every corrupting influence that stands in the way of recognizing all of creation as the work of God, as God's active Self-disclosure or theophany.[36] This is the way of Imam Al-Ghazali and of the majority of the Sufi orders.

On the other hand there is the path from the Signifier to His signs, from the Artisan to His works. In this branch the seeker experiences divine attraction (jadhba), and is able to enter the path with a glimpse of its endpoint, of direct apprehension of the Divine Presence towards which all spiritual striving is directed. This does not replace the striving to purify the heart, as in the other branch; it simply stems from a different point of entry into the path. This is the way primarily of the masters of the Naqshbandi and Shadhili orders.[37]

Contemporary scholars may also recognize a third branch, attributed to the late Ottoman scholar Said Nursi and explicated in his vast Qur'ân commentary called the Risale-i Nur. This approach entails strict adherence to the way of the Prophet Muhammad, in the understanding that this wont, or sunnah, proposes a complete devotional spirituality adequate to those without access to a master of the Sufi way.[38]

[edit] Contributions to other domains of scholarship

Sufism has contributed significantly to the elaboration of theoretical perspectives in many domains of intellectual endeavor. For instance, the doctrine of "subtle centers" or centers of subtle cognition (known as Lataif-e-sitta) addresses the matter of the awakening of spiritual intuition[39] in ways that some consider similar to certain models of chakra in Hinduism. In general, these subtle centers or latâ'if are thought of as faculties that are to be purified sequentially in order to bring the seeker's wayfaring to completion. A concise and useful summary of this system from a living exponent of this tradition has been published by Muhammad Emin Er.[40]

Sufi psychology has influenced many areas of thinking both within and outside of Islam, drawing primarily upon three concepts. Ja'far al-Sadiq (both an imam in the Shia tradition and a respected scholar and link in chains of Sufi transmission in all Islamic sects) held that human beings are dominated by a lower self called the nafs, a faculty of spiritual intuition called the qalb or spiritual heart, and a spirit or soul called ruh. These interact in various ways, producing the spiritual types of the tyrant (dominated by nafs), the person of faith and moderation (dominated by the spiritual heart), and the person lost in love for God (dominated by the ruh).[41]

Of note with regard to the spread of Sufi psychology in the West is Robert Frager, a Sufi teacher authorized in the Halveti Jerrahi order. Frager was a trained psychologist, born in the United States, who converted to Islam in the course of his practice of Sufism and wrote extensively on Sufism and psychology.[42]

Sufi cosmology and Sufi metaphysics are also noteworthy areas of intellectual accomplishment.

[edit] Sufi practices

The devotional practices of Sufis vary widely. This is because an acknowledged and authorized master of the Sufi path is in effect a physician of the heart, able to diagnose the seeker's impediments to knowledge and pure intention in serving God, and to prescribe to the seeker a course of treatment appropriate to his or her maladies. The consensus among Sufi scholars is that the seeker cannot self-diagnose, and that it can be extremely harmful to undertake any of these practices alone and without formal authorization.[43]

Prerequisites to practice include rigorous adherence to Islamic norms (ritual prayer in its five prescribed times each day, the fast of Ramadan, and so forth). Additionally, the seeker ought to be firmly grounded in supererogatory practices known from the life of the Prophet Muhammad (such as the so-called "sunna prayers"). This is in accordance with the words, attributed to God, of the following, a famous Hadith Qudsi:

My servant draws near to Me through nothing I love more than that which I have made obligatory for him. My servant never ceases drawing near to Me through supererogatory works until I love him. Then, when I love him, I am his hearing through which he hears, his sight through which he sees, his hand through which he grasps, and his foot through which he walks.

It is also necessary for the seeker to have a correct creed (Aqidah),[44] and to embrace with certainty its tenets.[45] The seeker must also, of necessity, turn away from sins, love of this world, the love of company and renown, obedience to satanic impulse, and the promptings of the lower self. (The way in which this purification of the heart is achieved is outlined in certain books, but must be prescribed in detail by a Sufi master.) The seeker must also be trained to prevent the corruption of those good deeds which have accrued to his or her credit by overcoming the traps of ostentation, pride, arrogance, envy, and long hopes (meaning the hope for a long life allowing us to mend our ways later, rather than immediately, here and now).

Sufi practices, while attractive to some, are not a means for gaining knowledge. The traditional scholars of Sufism hold it as absolutely axiomatic that knowledge of God is not a psychological state generated through breath control. Thus, practice of "techniques" is not the cause, but instead the occasion for such knowledge to be obtained (if at all), given proper prerequisites and proper guidance by a master of the way. Furthermore, the emphasis on practices may obscure a far more important fact: The seeker is, in a sense, to become a broken person, stripped of all habits through the practice of (in the words of Imam Al-Ghazali words) solitude, silence, sleeplessness, and hunger.[46]

[edit] Dhikr

Dhikr is the remembrance of God commanded in the Qur'an for all Muslims. To engage in dhikr is to practice consciousness of the Divine Presence (some would say "to seek a state of godwariness") according to a variety of means. Some types of dhikr are prescribed for all Muslims, and do not require Sufi initiation or the prescription of a Sufi master because they are deemed to be good for every seeker under every circumstance.[47] Other types of dhikr require specific instruction and permission.

Dhikr as a devotional act includes the repetition of divine names, supplications and aphorisms from hadith literature, and sections of the Qur'an. More generally, any activity in which the Muslim maintains awareness of God is considered dhikr.

Some Sufi orders stress and extensive reliance upon Dhikr and termed it the source to attain Divine Love likewise in Qadri Al-Muntahi Sufi tariqa, which was originated by Riaz Ahmed Gohar Shahi. This practice of Dhikr called Dhikr-e-Qulb(remembrance of Allah by Heartbeats). The basic idea of this practice is to visualize the Arabic name of God, Allah as having been written on the disciple's heart.[48]

Some Sufi orders engage in ritualized dhikr ceremonies, the liturgy of which may include recitation, singing, instrumental music, dance, costumes, incense, meditation, ecstasy, and trance.[49]

[edit] Muraqaba

The practice of muraqaba can be likened to the practices of meditation attested in many faith communities. The word muraqaba is derived from the same root (r-q-b) occurring as one of the 99 Names of God in the Qur'an, al-Raqîb, meaning "the Vigilant" and attested in verse 4: 1 of the Qur'an. Through muraqaba, a person watches over or takes care of the spiritual heart, acquires knowledge about it, and becomes attuned to the Divine Presence, which is ever vigilant.

While variation exists, one description of the practice within a Naqshbandi lineage reads as follows:

He is to collect all of his bodily senses in concentration, and to cut himself off from all preoccupation and notions that inflict themselves upon the heart. And thus he is to turn his full consciousness towards God Most High while saying three times: “Ilahî anta maqsûdî wa-ridâka matlûbî — my God, you are my Goal and Your good pleasure is what I seek.” Then he brings to his heart the Name of the Essence — Allâh — and as it courses through his heart he remains attentive to its meaning, which is “Essence without likeness.” The seeker remains aware that He is Present, Watchful, Encompassing of all, thereby exemplifying the meaning of his saying (may God bless him and grant him peace): “Worship God as though you see Him, for if you do not see Him, He sees you.” And likewise the prophetic tradition: “The most favored level of faith is to know that God is witness over you, wherever you may be.”[50]

[edit] Sufi pilgrimages

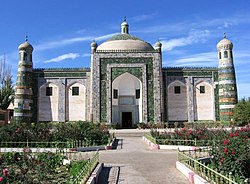

In popular Sufism (i.e., devotional practices that have achieved currency in world cultures through Sufi influence), one common practice is to visit the tombs of saints, great scholars, and righteous people. This is a particularly common practice in South Asia, where famous tombs include those of Khoja Afāq, near Kashgar, in China; Sachal Sarmast, in Sindh, Pakistan; and the Darbar-e-Gohar Shahi in Kotri Sharif. Likewise, in Fez, Morocco, a popular destination for such pious visitation is the Zaouia Moulay Idriss II and the yearly visitation to see the current Sheikh of the Qadiri Boutchichi Tariqah, Sheikh Sidi Hamza al Qadiri al Boutchichi to celebrate the Mawlid (which is usually televised on Mocorran National television).

Visitors may invoke blessings upon those interred, and seek divine favor and proximity.

[edit] Islam and Sufism

[edit] Sufism and Islamic law

Scholars and adherents of Sufism sometimes describe Sufism in terms of a threefold approach to God as explained by a tradition (hadîth) attributed to the Prophet Muhammad,"The Shariah is my words, the tariqa is my actions, and the haqiqa is my interior states". Sufis believe the shariah, tariqa and haqiqa are mutually interdependent.[51] The tariqa, the ‘path’ on which the mystics walk, has been defined as ‘the path which comes out of the Shariah, for the main road is called shar, the path, tariq.’ No mystical experience can be realized if the binding injunctions of the Shariah are not followed faithfully first. The path, tariqa, however, is narrower and more difficult to walk. It leads the adept, called sâlik (wayfarer), in his sulûk (wayfaring), through different stations (maqâmât) until he reaches his goal, the perfect tawhîd, the existential confession that God is One.[52]

[edit] Traditional Islamic thought and Sufism

The literature of Sufism emphasizes highly subjective matters that resist outside observation, such as the subtle states of the heart. Often these resist direct reference or description, with the consequence that the authors of various Sufi treatises took recourse to allegorical language. For instance, much Sufi poetry refers to intoxication, which Islam expressly forbids. This usage of indirect language and the existence of interpretations by people who had no training in Islam or Sufism led to doubts being cast over the validity of Sufism as a part of Islam. Also, some groups emerged that considered themselves above the Sharia and discussed Sufism as a method of bypassing the rules of Islam in order to attain salvation directly. This was disapproved of by traditional scholars.

For these and other reasons, the relationship between traditional Islamic scholars and Sufism is complex and a range of scholarly opinion on Sufism in Islam has been the norm. Some scholars, such as Al-Ghazali, helped its propagation while other scholars, such as Ibn Taymiyyah, opposed it. W. Chittick explains the position of Sufism and Sufis this way:

In short, Muslim scholars who focused their energies on understanding the normative guidelines for the body came to be known as jurists, and those who held that the most important task was to train the mind in achieving correct understanding came to be divided into three main schools of thought: theology, philosophy, and Sufism. This leaves us with the third domain of human existence, the spirit. Most Muslims who devoted their major efforts to developing the spiritual dimensions of the human person came to be known as Sufis.

[edit] Traditional and non-traditional Sufi groups

The traditional Sufi orders, which are in majority, emphasize the role of Sufism as a spiritual discipline within Islam. Therefore, the Sharia (traditional Islamic law) and the Sunnah (customs of the Prophet) are seen as crucial for any Sufi aspirant. One proof traditional orders assert is that almost all the famous Sufi masters of the past Caliphates were experts in Sharia and were renowned as people with great Iman (faith) and excellent practice. Many were also Qadis (Sharia law judges) in courts. They held that Sufism was never distinct from Islam and to fully comprehend and practice Sufism one must be an observant Muslim.

In recent decades there has been a growth of non-traditional Sufi movements in the West. Examples include the Universal Sufism movement, the Golden Sufi Center, the Sufi Foundation of America, the neo-sufism of Idries Shah, and Sufism Reoriented. Rumi has become one of the most widely read poets in the United States, thanks largely to the translations published by Coleman Barks.

[edit] Islamic positions on non-Islamic Sufi groups

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2008) |

| This article may be inaccurate or unbalanced in favor of certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. |

The use of the title Sufi by non-traditional groups to refer to themselves, and their appropriation of traditional Sufi masters (most notably Jalaluddin Rumi) as sources of authority or inspiration, is not accepted by Muslims who are Sufi adherents.

Some traditional Sufis also object to interpretations of classical Sufis texts by writers who have no grounding in the traditional Islamic sciences and therefore no prerequisites for understanding such texts. These are considered by certain conventional Islamic scholars as beyond the pale of the religion.[53] This being said, there are Islamic Sufi groups that are open to non-Muslim participation.

[edit] Reception

[edit] Criticism within Islam

Riaz Ahmed Gohar Shahi was heavily criticized by orthodox theological scholars in Pakistan and abroad. Shahi's books were banned by the Government of Pakistan.[54] Public meetings are not allowed to his followers[55] and no press coverage is allowed to either Gohar Shahi or to his followers due to charges of blasphemy law violations. Many attempts were made on Shahi's life including a petrol bomb attack, thrown into his Manchester residence,[56] and an attack with a hand grenade during the discourse at his home in Kotri, Pakistan.[56] Gohar Shahi was booked in 1997 on alleged charges of murdering a woman who had come to him for spiritual treatment;[57] Gohar Shahi, and many of his followers,[58] were later convicted under Islamic blasphemy laws[59][60] by an antiterrorist court in Sindh.[61] Gohar Shahi was convicted in absentia[59]—as then he was in England[58]—resulting in sentences that totaled approximately 59 years.[60] Gohar Shahi died abroad, prior to any decision on appeals filed with the High Court of Sindh.[60]

[edit] Perception outside Islam

Sufi mysticism has long exercised a fascination upon the Western world, and especially its orientalist scholars.[62] Figures like Rumi have become household names in the United States, where Sufism is perceived as quietist and less political.[62]

The Islamic Institute in Mannheim, Germany, which works towards the integration of Europe and Muslims, sees Sufism as particularly suited for interreligious dialogue and intercultural harmonisation in democratic and pluralist societies; it has described Sufism as a symbol of tolerance and humanism – undogmatic, flexible and non-violent.[63] The Indian government has likewise praised Sufism as the tolerant face of Islam though many believe that Sufis like Naqshbandis have been fanatical and that some of the Sufi traditions like dancing, copied from native Indian traditions help in camouflaging Islamic extremism.[62]

[edit] The Influence of Sufism on Judaism

A great influence was exercised by Sufism upon the ethical writings of Jews in the middle ages. In the first writing of this kind, we see "Kitab al-Hidayah ila Fara'iḍ al-Ḳulub", Duties of the Heart, of Bahya ibn Pakuda. This book was translated by Judah ibn Tibbon into Hebrew under the title "Ḥobot ha-Lebabot".

The author says: "The precepts prescribed by the Torah number 613 only; those dictated by the intellect are innumerable." This was precisely the argument used by the Sufis against their adversaries, the Ulamas. The arrangement of the book seems to have been inspired by Sufism. Its ten sections correspond to the ten stages through which the Sufi had to pass in order to attain that true and passionate love of God which is the aim and goal of all ethical self-discipline. It is noteworthy that in the ethical writings of the Sufis Al-Kusajri and Al-Harawi there are sections which treat of the same subjects as those treated in the "Ḥobot ha-Lebabot" and which bear the same titles: e.g., "Bab al-Tawakkul"; "Bab al-Taubah"; "Bab al-Muḥasabah"; "Bab al-Tawaḍu'"; "Bab al-Zuhd". In the ninth gate Baḥya directly quotes sayings of the Sufis, whom he calls "Perushim. "However, the author of the "Ḥobot ha-Lebabot" did not go so far as to approve of the asceticism of the Sufis, although he showed a marked predilection for their ethical principles.

The Jewish write Abraham bar Ḥiyya teaches the asceticism of the Sufis. His distinction with regard to the observance of Jewish law by various classes of men is essentially a Sufic theory. According to it there are four principal degrees of human perfection or sanctity; namely:

- (1) of "Shari'ah," i.e., of strict obedience to all ritual laws of Islam, such as prayer, fasting, pilgrimage, almsgiving, ablution, etc., which is the lowest degree of worship, and is attainable by all

- (2) of "Ṭariḳah," which is accessible only to a higher class of men who, while strictly adhering to the outward or ceremonial injunctions of religion, rise to an inward perception of mental power and virtue necessary for the nearer approach to the Divinity

- (3) of "Ḥaḳikah," the degree attained by those who, through continuous contemplation and inward devotion, have risen to the true perception of the nature of the visible and invisible; who, in fact, have recognized the Godhead, and through this knowledge have succeeded in establishing an ecstatic relation to it; and

- (4) of the "Ma'arifah," in which state man communicates directly with the Deity.

[edit] In popular culture

[edit] In movies

The movie Bab´Aziz (2005) directed by Nacer Khemir tells the story of an old and blind dervish who must cross the desert with his little granddaughter during many days and nights to get to his last dervish reunion celebrated every 30 years. The movie is full of Sufi mysticism and even contain quotes of Rumi and other sufi poets and shows an ecstatic sufi dance.

[edit] In music

Madonna on her record Bedtime Stories (1994) sings a song called Bedtime Story that talks about getting in a high unconsciousness level. The video for the song shows an ecstatic sufi ritual with many dervishes dancing around, Arabic calligraphy and some other Sufi elements. In the year 1998 she recorded the song Bittersweet in which she recites Rumi´s poem by the same name. In the year 2001 Madonna sang the song Secret during her Drowned World Tour showing rituals from many religions including a Sufi dance. Singer/songwritter Loreena McKennit on her record The Mask And Mirror (1994) has a song called The Mystic´s Dream clearly influenced by Sufi music and poetry. The band, mewithoutYou, has made references to sufi parables, including the name of their upcoming album "it's all crazy! it's all false! it's all a dream! it's alright!" (2009) Lead singer, Aaron Weiss, claims this influence comes from his parents who are both sufi converts.

A.R. Rahman, the Academy award winner (2009) the follower of Sufi principles, scored music about Sufism in the film Jodhaa Akbar[2] for the song Khwaja Mere Khwaja.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ a b Dr. Alan Godlas, University of Georgia, Sufism's Many Paths, 2000, University of Georgia: http://www.uga.edu/islam/Sufism.html

- ^ Nuh Ha Mim Keller, "How would you respond to the claim that Sufism is Bid'a?", 1995. Fatwa accessible at: http://www.masud.co.uk/ISLAM/nuh/sufism.htm

- ^ Dr. Zubair Fattani, 'The meaning of Tasawwuf', Islamic Academy. See: http://www.islamicacademy.org/html/Articles/English/Tasawwuf.htm

- ^ Ahmed Zarruq, Zaineb Istrabadi, Hamza Yusuf Hanson - "The Principles of Sufism." Amal Press. 2008.

- ^ An English translation of Shaykh Ahmad ibn Ajiba's biography has been published by Fons Vitae.

- ^ Michael Sells, Early Islamic Mysticism, pg. 1

- ^ Idries Shah, The Sufis, ISBN 0-385-07966-4

- ^ Egyptian Mystics: Seekers of the Way ISBN-13: 978-1-931446-05-1 or ISBN-10: 1-931446-05-9

- ^ Haddad, Gibril Fouad: Sufism in Islam LivingIslam.org: http://www.livingislam.org/k/si_e.html

- ^ Sufism, Sufis, and Sufi Orders: Sufism's Many Paths

- ^ Abdullah Nur ad-Din Durkee, The School of the Shadhdhuliyyah, Volume One: Orisons, ISBN 9770018309

- ^ Muhammad Emin Er, Laws of the Heart: A Practical Introduction to the Sufi Path, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815196-1-6

- ^ Abdullah Nur ad-Din Durkee, The School of the Shadhdhuliyyah, Volume One: Orisons; see also Shaykh Muhammad Hisham Kabbani, Classical Islam and the Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition, ISBN 9781930409231, which reproduces the spiritual lineage (silsila) of a living Sufi master.

- ^ Shaykh Muhammad Hisham Kabbani, Classical Islam and the Naqshbandi Sufi Tradition, ISBN 9781930409231

- ^ See Muhammad Emin Er, Laws of the Heart: A Practical Introduction to the Sufi Path, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815196-1-6, for a detailed description of the practices and preconditions of this sort of spiritual retreat.

- ^ See examples provided by Muzaffar Ozak in Irshad: Wisdom of a Sufi Master, addressed to a general audience rather than specifically to his own students.

- ^ a b Cavendish, Richard. Great Religions. New York: Arco Publishing, 1980.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel. [1]

- ^ Massignon, Louis. Essai sur les origines du lexique technique de la mystique musulmane. Paris: Vrin, 1954. p. 104.

- ^ Imam Birgivi, The Path of Muhammad, WorldWisdom, ISBN 0941532682

- ^ For an introduction to these and other early exemplars of the Sufi approach, see Michael Sells (ed.), Early Islamic Mysticism: Sufi, Qur'an, Mi'raj, Poetic and Theological Writings, ISBN 978-0809136193.

- ^ J. Spencer Trimingham, The Sufi Orders in Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195120585.

- ^ The most recent version of the Risâla is the translation of Alexander Knysh, Al-Qushayri's Epistle on Sufism: Al-risala Al-qushayriyya Fi 'ilm Al-tasawwuf (ISBN 978-1859641866). Earlier translations include a partial version by Rabia Terri Harris (Sufi Book of Spiritual Ascent) and complete versions by Harris, and Barbara R. Von Schlegell.

- ^ Several sections of the Revival of Religious Sciences have been published in translation by the Islamic Texts Society; see http://www.fonsvitae.com/sufism.html. The Alchemy of Happiness has been published in a complete translation by Claud Field (ISBN 978-0935782288), and presents the argument of the much larger Revival of Religious Sciences in summary form.

- ^ For the pre-modern era, see Vincent J. Cornell, Realm of the Saint: Power and Authority in Moroccan Sufism, ISBN 978-0292712096; and for the colonial era, Knut Vikyr, Sufi and Scholar on the Desert Edge: Muhammad B. Oali Al-Sanusi and His Brotherhood, ISBN 978-0810112261.

- ^ Dina Le Gall, A Culture of Sufism: Naqshbandis in the Ottoman World, 1450-1700 , ISBN 978-0791462454.

- ^ Arthur F. Buehler, Sufi Heirs of the Prophet: The Indian Naqshbandiyya and the Rise of the Mediating Sufi Shaykh, ISBN 978-1570037832.

- ^ Victor Danner - "The Islamic Tradition: An introduction." Amity House. February 1988.

- ^ See in particular the biographical introduction to Michel Chodkiewicz, The Spiritual Writings of Amir Abd Al-Kader, ISBN 978-0791424469.

- ^ "Sufism and Religious Brotherhoods in Senegal," Babou, Cheikh Anta, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, v. 40 no1 (2007) p. 184-6

- ^ Sufism and Religious Brotherhoods in Senegal, Khadim Mbacke, translated from the French by Eric Ross and edited by John Hunwick. Princeton, N.J.: Markus Wiener, 2005.

- ^ “The Jamaat Tableegh and the Deobandis” by Sajid Abdul Kayum, Chapter1: Overview and Background.

- ^ http://www.uga.edu/islam/Sufism.html

- ^ http://www.sulthaniya.com/almurshid1.html

- ^ Muhammad Emin Er, Laws of the Heart: A Practical Introduction to the Sufi Path, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815196-1-6

- ^ For a systematic description of the diseases of the heart that are to be overcome in order for this perspective to take root, see Hamza Yusuf, Purification of the Heart: Signs, Symptoms and Cures of the Spiritual Diseases of the Heart, ISBN 978-1929694150.

- ^ Concerning this, and for an excellent discussion of the concept of attraction (jadhba), see especially the Introduction to Abdullah Nur ad-Din Durkee, The School of the Shadhdhuliyyah, Volume One: Orisons, ISBN 9770018309.

- ^ Muhammad Emin Er, al-Wasilat al-Fasila, unpublished MS.

- ^ Realities of The Heart Lataif

- ^ Muhammad Emin Er, Laws of the Heart: A Practical Introduction to the Sufi Path, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815196-1-6

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of Islam, ISBN 978-0807812716 .

- ^ See especially Robert Frager, Heart, Self & Soul: The Sufi Psychology of Growth, Balance, and Harmony, ISBN 978-0835607780.

- ^ Hakim Moinuddin Chisti, The Book of Sufi Healing, ISBN 978-0892810437

- ^ For an introduction to the normative creed of Islam as espoused by the consensus of scholars, see Hamza Yusuf, The Creed of Imam al-Tahawi, ISBN 978-0970284396, and Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Maghnisawi, Imam Abu Hanifa's Al-Fiqh Al-Akbar Explained, ISBN 978-1933764030.

- ^ The meaning of certainty in this context is emphasized in Muhammad Emin Er, The Soul of Islam: Essential Doctrines and Beliefs, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815196-0-9.

- ^ See in particular the introduction by T. J. Winter to Abu Hamid Muhammad al-Ghazali, Al-Ghazali on Disciplining the Soul and on Breaking the Two Desires: Books XXII and XXIII of the Revival of the Religious Sciences, ISBN 978-0946621439.

- ^ An example of a formula of dhikr requiring no special permission is given by Hakim Moinuddin Chisti in the final chapter of The Book of Sufi Healing, ISBN 978-0892810437.

- ^ WHAT IS REMEMBRANCE AND WHAT IS CONTEMPLATION?

- ^ Touma 1996, p.162

- ^ Muhammad Emin Er, Laws of the Heart: A Practical Introduction to the Sufi Path, ISBN 978-0-9815196-1-6, p. 77.

- ^ Muhammad Emin Er, The Soul of Islam: Essential Doctrines and Beliefs, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9815196-0-9.

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Dimentions of Islam (1975) pg.99

- ^ Sufism is not Islam: A Comparative Study ISBN 8186030352 http://www.exoticindiaart.com/book/details/IDE944/

- ^ Pakistan's Supreme Court upholds ban on a Shahi disciple's book

- ^ 10 held for raising slogans in favour of Gohar Shahi

- ^ a b Attempts made on Gohar Shahi

- ^ Gohar Shahi Chief of ASI

- ^ a b Int’l Religious Freedom Report - May, 2001

- ^ a b Country Reports on Human Rights Practices by United States of America

- ^ a b c "The Man in the Moon" by Ardeshir Cowasjee

- ^ U.S. State Department Religious Freedom Report 2000

- ^ a b c Ron Geaves, Theodore Gabriel, Yvonne Haddad, Jane Idleman Smith: Islam and the West Post 9/11, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., p. 67

- ^ Jamal Malik, John R. Hinnells: Sufism in the West, Routledge, p. 25

[edit] Additional Reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Sufism |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of |

- Dahlen, Ashk. Sufi Islam, The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations, ed. Peter B. Clarke & Peter Beyer, New York, 2009.

- Dahlen, Ashk. Female Sufi Saints and Disciples: Women in the life of Jalal al-din Rumi, Orientalia Suecana, vol. 57, Uppsala, 2008.

- Al-Badawi, Mostafa. Sufi Sage of Arabia. Louisville: Fons Vitae, 2005.

- Ali-Shah, Omar. The Rules or Secrets of the Naqshbandi Order, Tractus Publishers, 1992, ISBN 978-2-909347-09-7.

- Arberry, A.J.. Mystical Poems of Rumi, Vols. 1&2. Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, 1991.

- Austin, R.W.J.. Sufis of Andalusia, Gloustershire: Beshara Publications, 1988.

- Bewley, Aisha. The Darqawi Way. London: Diwan Press, 1981.

- Burckhardt, Titus. An Introduction to Sufi Doctrine. Lahore: 1963.

- Colby, Frederick. The Subtleties of the Ascension: Lata'if Al-Miraj: Early Mystical Sayings on Muhammad's Heavenly Journey. City: Fons Vitae, 2006.

- Emin Er, Muhammad. Laws of the Heart: A Practical Introduction to the Sufi Path, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 9780981519616.

- Emin Er, Muhammad. The Soul of Islam: Essential Doctrines and Beliefs, Shifâ Publishers, 2008, ISBN 9780981519609.

- Ernst, Carl. The Shambhala Guide to Sufism. HarperOne, 1999.

- Fadiman, James and Frager, Robert. Essential Sufism. Boulder: Shambhala, 1997.

- Farzan, Massud. The Tale of the Reed Pipe. New York: Dutton, 1974.

- Gowins, Phillip. Sufism - A Path for Today: The Sovereign Soul. New Delhi: Readworthy Publications (P) Ltd., 2008. ISBN 9788189973490

- Jean-Louis Michon. The Autobiography (Fahrasa) of a Moroccan Soufi: Ahmad Ibn `Ajiba (1747-1809). Louisville: Fons Vitae, 1999.

- Hazrat Inayat Khan, The Sufi message, Volume IX - The Unity of Religious Ideals, Part VI, SUFISM - http://wahiduddin.net/mv2/IX/IX_31.htm

- Lewinsohn (ed.), The Heritage of Sufism, Volume I: Classical Persian Sufism from its Origins to Rumi (700-1300).

- Nurbakhsh, Javad, What is Sufism? electronic text derived from The Path, Khaniqahi Nimatullahi Publications, London, 2003 ISBN 0-933546-70-X.

- Rahimi, Sadeq (2007). Intimate Exteriority: Sufi Space as Sanctuary for Injured Subjectivities in Turkey., Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 46, No. 3, September 2007; pp. 409-422

- Schmidle, Nicholas, "Pakistan's Sufis Preach Faith and Ecstasy", Smithsonian magazine, December 2008

- Shah, Idries. The Sufis. New York: Anchor Books, 1971, ISBN 0385079664.

- Shah, Idries. The Sufis.www.moinuddinchishty.com/mv2/IX/IX_31.htm

[edit] External links

- Sufism at the Open Directory Project

- Sufifinder - Rough Guide to Spirituality

- Sufism's Many Paths

- Sufism in a Nutshell: Introduction & Stations of Progress

- Articles on Sufism

- When mothers rule: The right to choose from a Sufi perspective, Ruba Saqr, Forward Magazine

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||