Glenn Gould

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Glenn Gould | |

|---|---|

Gould rehearsing in 1974

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Glenn[1] Herbert Gold[2] |

| Born | September 25, 1932 |

| Died | October 4, 1982 (aged 50) |

| Genre(s) | Classical |

| Occupation(s) | Pianist, Composer |

| Years active | fl. 1945-1982 |

| Website | The Glenn Gould Foundation |

Glenn Herbert Gould[1][2] (September 25, 1932 – October 4, 1982) was a Canadian pianist noted especially for his recordings of the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, remarkable technical proficiency, unorthodox musical philosophy, and eccentric personality and piano technique. He is one of the best known and most celebrated pianists of the twentieth century. He stopped performing concerts in 1964, dedicating himself to the recording studio for the rest of his career—as well as performances for television and radio, non-musical radio documentaries, and other projects.

Contents |

[edit] Life

Glenn Herbert Gould[1][2] was born at home in Toronto on September 25, 1932, to Russell Herbert ("Bert") Gould and Florence ("Flora") Emma Gould (née Greig),[3] Presbyterians of Scottish and English ancestry. His maternal grandfather was a cousin of Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg.[4] The family's surname was changed to Gould informally around 1939 in order to avoid being mistaken as Jewish, due to a series of reasons centring on 'the prevailing anti-Semitism of pre-war Toronto' and the Gold surname's Jewish association.[5] Gould had no Jewish ancestry,[6] though sometimes made jokes on the subject, e.g: "When people ask me if I'm Jewish, I always tell them that I was Jewish during the war."[7]

Gould's interest in music, and his talent as a pianist, became evident very early on. Both his parents were musical and his mother, especially, encouraged the infant Gould's early musical development. He had perfect pitch and could read music before he could read words.[8] At a young age, he reportedly behaved differently from typical children at the piano: he would strike single notes and listen to their long decay.[9] Gould's first piano teacher was his mother until the age of ten. At ten he began attending the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, where he studied piano with Alberto Guerrero, organ with Frederick C. Silvester and theory with Leo Smith.

At an early age Gould became interested in composition, and played his own little pieces for family, friends, and sometimes larger gatherings. For example in 1938, in the company of his mother, Gould attended the Emmanuel Presbyterian Church, a few blocks from the Gould house, and performed one of his own compositions.[10]

When he was six, Glenn was taken for the first time to hear a live musical performance by a celebrated soloist, which had a tremendous impact on him. He later described the experience:

- "It was Hofmann. It was, I think, his last performance in Toronto, and it was a staggering impression. The only thing I can really remember is that, when I was being brought home in a car, I was in that wonderful state of through your mind. They were all orchestral sounds, but I was playing them all, and suddenly I was Hofmann. I was enchanted."

In 1945, he gave his first public performance, playing the organ, and the following year he made his first appearance with an orchestra, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, in a performance of Beethoven's 4th piano concerto. His first public recital followed in 1947, and his first recital on radio came with the CBC in 1950. This was the beginning of his long association with radio and recording.

In 1957, Gould toured the Soviet Union, becoming the first North American to play there since World War II. His concerts featured Bach, Beethoven, and the serial music of Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg, which had been suppressed in the Soviet Union during the era of Socialist Realism.

On April 10, 1964, Gould gave his last public performance, playing in Los Angeles, California, at the Wilshire Ebell Theater.[11] Among the pieces he performed that night were Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 30, selections from Bach's The Art of Fugue, and the Piano Sonata No. 3, Op. 92 No. 4 by Ernst Krenek. Oddly, a recording exists in which Gould claims the event took place in Chicago. For the rest of his life he eschewed live performance, focusing instead on recording, writing, and broadcasting. Towards the end of his life he began conducting; he had earlier directed Bach's Brandenburg concerto no.5 and cantata BWV 54, Widerstehe doch der Sünde from the harpsipiano (a piano with metal hammers to simulate harpsichord sound) in the 1960s. His last recording was as a conductor, Wagner's Siegfried Idyll in its original chamber music scoring. He had intended to give up the piano at the age of 50, spending later years conducting, writing on music and composing.

During his life he suffered many pains and ailments, though was something of a hypochondriac,[12] and his autopsy revealed few underlying problems in areas that often troubled him.[13]

He suffered a stroke on 27 September 1982, which paralyzed the left side of his body. He was admitted to the hospital and his condition rapidly deteriorated. He was taken off life support on October 4.[14] He is buried in Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

[edit] Gould as a pianist

Gould was known for his vivid musical imagination, and listeners regarded his interpretations as ranging from brilliantly creative to, on occasion, outright eccentric. His piano playing had great clarity, particularly in contrapuntal passages. He was considered a child prodigy and in adulthood was also described as a musical phenomenon. As he played, he often swayed his torso, almost always in a clockwise motion.[15]

When Gould was around ten years old, he injured his back as a result of a fall from a boat ramp on the shore of Lake Simcoe.[16] This incident is almost certainly not related to his father's subsequent construction for him of an adjustable-height chair, which he used for the rest of his life. This famous chair was designed so that Gould could sit very low at the keyboard with the object of pulling down on the keys rather than striking them from above — a central technical idea of his teacher, Alberto Guerrero,[17] seen in the above-right photograph from 1945. Gould's mother urged the young Gould to sit up straight at the keyboard,[18] which is how we see him with Guerrero in 1945 before he had fully developed his mature technique.

Gould developed a formidable technique. It enabled him to choose very fast tempos while retaining the separateness and clarity of each note. His extremely low position at the instrument arguably permitted more control over the keyboard. According to the pianist Charles Rosen, however, a low position at the piano is unsuitable for playing the technically demanding music of the 19th century. Nevertheless, this did not seem to impede Gould, as he showed considerable technical skill in both his recordings of Bach and in virtuosic and romantic works like his own arrangement of Ravel's La Valse and his playing of Liszt's transcriptions of Beethoven's fifth and sixth symphonies. Gould worked from a young age with his teacher Alberto Guerrero on a technique known as finger-tapping, a method of training the fingers to act more independently from the arm.

Gould claimed he almost never practiced on the piano, preferring to study music by reading it rather than playing it, a technique he had also learned from Guerrero. His manual practicing was unusually attentive to articulation, rather than exercises for basic facility. He may have spoken ironically about his practicing, but there is evidence that he did, at least occasionally, practice Bach and Beethoven in a way that was nuanced and efficient.[19]

He stated that he didn't understand the requirement of other pianists to continuously reinforce their relationship with the instrument by practicing many hours a day.[20] It seems that Gould was able to practice mentally without access to an instrument, and even took this so far as to prepare for a recording of Brahms piano works without ever playing them until a few weeks before the recording sessions. This is all the more staggering considering the absolute accuracy and phenomenal dexterity exhibited in his playing. Gould's large repertoire also demonstrated this natural mnemonic gift.

Regarding the performance of Bach on the piano, Gould said, "the piano is not an instrument for which I have any great love as such... [But] I have played it all my life and it is the best vehicle I have to express my ideas." In the case of Bach, Gould admitted, "[I] fixed the action in some of the instruments I play on — and the piano I use for all recordings is now so fixed — so that it is a shallower and more responsive action than the standard. It tends to have a mechanism which is rather like an automobile without power steering: you are in control and not it; it doesn't drive you, you drive it. This is the secret of doing Bach on the piano at all. You must have that immediacy of response, that control over fine definitions of things."[21]

Of significant influence upon the teenage Gould were Artur Schnabel (Gould: "The piano was a means to an end for him, and the end was to approach Beethoven"); Rosalyn Tureck's recordings of Bach ("upright, with a sense of repose and positiveness"); and Leopold Stokowski.[22]

Gould had a pronounced aversion to what he termed a ‘hedonistic’ approach to the piano repertoire, performance and music generally. For Gould, ‘hedonism’ in this sense denoted a superficial theatricality, something to which he felt Mozart, for example, became increasingly susceptible later in his career.[23] He associated this drift towards ‘hedonism’ with the emergence of a cult of showmanship and gratuitous virtuosity on the concert platform in the nineteenth century and later on. The institution of the public concert, he felt, degenerated into the 'blood sport' with which he struggled, and which he ultimately rejected.[24]

[edit] Recordings

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Problems listening to these files? See media help. | |||||||||||||||||

In creating music, Gould much preferred the control and intimacy provided by the recording studio, and he disliked the concert hall, which he compared to a competitive sporting arena. After his final public performance in 1964, he devoted his career solely to the studio, recording albums and several radio documentaries. He was attracted to the technical aspects of recording, and considered the manipulation of tape to be another part of the creative process. Although his producer at CBS, Andrew Kazdin, has stated that he was the classical artist least in need of splices or dubs, Gould used the process to give him total artistic control over a recording. He recounted his recording of the A minor fugue from Book I of the Well-Tempered Clavier, and how it was spliced together from two takes, with the fugue's expositions from one take and its episodes from another.[25]

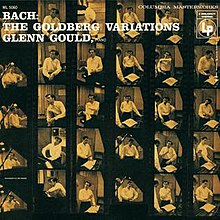

Gould's first major recording, The Goldberg Variations came in 1955, at Columbia Masterworks' 30th Street Studios in New York City. Although there was initially some controversy at CBS as to whether this was the most appropriate piece to record, the finished product received phenomenal praise, and was among the best-selling classical music albums of its time. Gould became closely associated with the piece, playing it in full or in part at many of his recitals. Another version of the Goldberg Variations, recorded in 1981, would be among his last recordings, and one of only a few pieces he recorded twice in the studio. The 1981 recording was one of CBS Masterworks' first digital recordings. The two recordings are very different, the first highly energetic and often frenetic, the second slower and more introspective; in it, Gould treats the Aria and its thirty variations as one cohesive piece. There are also two other recordings of the Goldberg Variations; one is a live recording from 1954 (CBC PSCD2007) the other is a live recording from Salzburg in 1959 (Sony SRCR-9500).

Gould recorded most of Bach's other keyboard works, including the complete Well-Tempered Clavier, Partitas, French Suites, English Suites and keyboard concertos. For his only recording at the organ, he recorded about half of The Art of Fugue. He also recorded all five of Beethoven's piano concertos and 23 of the 32 piano sonatas.

Gould also recorded works by many other prominent piano composers, though he was outspoken in his criticism of some of them, apparently not caring for Frédéric Chopin, for example. In a radio interview, when asked if he didn't find himself wanting to play Chopin, he replied: "No, I don't. I play it in a weak moment — maybe once a year or twice a year for myself. But it doesn't convince me." Although Gould recorded all of Mozart's sonatas and admitted enjoying the "actual playing" of them[26], he was a harsh critic of Mozart's music to the extent of arguing (perhaps a little puckishly) that Mozart died too late rather than too early.[27] He was fond of many lesser-known composers, such as the early keyboard music of Orlando Gibbons, who he claimed was his favourite composer in terms of Gibbons' spiritual quest in music, alongside his favouritism of Bach in general for his technical mastery.[28] He made recordings of piano music that was little known in North America, including music by Jean Sibelius (the sonatines, Kyllikki), Georges Bizet (the Variations Chromatiques de Concert and the Premier nocturne), Richard Strauss (the piano sonata, the five pieces, Enoch Arden), and Paul Hindemith (the three sonatas, the sonatas for brass and piano). He also made recordings of the complete piano works and Lieder of Arnold Schoenberg.

One of Gould's performances of the Prelude and Fugue in C Major from Book One of The Well-Tempered Clavier was chosen for inclusion on the NASA Voyager Golden Record by a committee headed by Carl Sagan. The disc of recordings was placed on the spacecraft Voyager 1, which is now approaching interstellar space and is the farthest human-made object from Earth.[29]

[edit] Collaborations

The success of Gould's collaborations with other artists was to a degree dependent upon their receptiveness to his sometimes unconventional readings of the music. His television collaboration with Yehudi Menuhin in 1965, recording works by Bach, Beethoven and Schoenberg[30] was deemed a success because 'Menuhin was ready to embrace the new perspective opened up by an unorthodox view'.[30] In 1966, his collaboration with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, however, recording Richard Strauss's Ophelia Lieder, op.67, was deemed an "outright fiasco".[30] Schwarzkopf believed in "total fidelity" to the score, but she also objected to the thermal conditions in the recording studio: "The studio was incredibly overheated, which may be good for a pianist but not for a singer: a dry throat is the end as far as singing is concerned. But we persevered nonetheless. It wasn't easy for me. Gould began by improvising something Straussian - we thought he was simply warming up, but no, he continued to play like that throughout the actual recordings, as though Strauss's notes were just a pretext that allowed him to improvise freely ...".[31]

[edit] Radio documentaries

Less well known is Gould's work in radio. This work was, in part, the result of Gould's long association with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, for which he produced numerous television and radio programs. Notable recordings include his Solitude Trilogy, consisting of The Idea of North, a meditation on Northern Canada and its people; The Latecomers, about Newfoundland; and The Quiet in the Land, on Mennonites in Manitoba. All three use a technique which Gould called "contrapuntal radio," in which several people are heard speaking at once, much like the voices in a fugue.

[edit] Lost footage of a live performance

In 2002, during preparations for Queen Elizabeth II's Jubilee Tour of Canada, lost footage of a Glenn Gould performance was discovered. It was part of a CBC program of various musical performances, which had followed the Queen's 1957 television address to Canadians from Rideau Hall, and featured a seven-minute live performance in which he plays the second and third movements of Bach's Keyboard Concerto in F Minor.[32]

[edit] Composition

As a teenager, Gould wrote chamber music and piano works in the style of the Second Viennese school of composition. His only significant work was the String Quartet, Op. 1, which he finished when he was in his 20s, and perhaps his cadenzas to Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1, which can be heard on his recording of the piece and have recently been recorded by the German pianist Lars Vogt.

Early works:

Slightly later works:

- Lieberson Madrigal (SATB and Piano)

- String Quartet Op. 1

- So You Want To Write A Fugue? (SATB with piano or string quartet accompaniment)

- Cadenzas to Beethoven's Piano concerto No. 1.

The majority of his work is published by Schott Music. The recording Glenn Gould: The Composer contains his original works excepting the cadenzas.

As well as composing, Gould was a prolific arranger of orchestral repertoire for piano. His arrangements include his Wagner and Ravel transcriptions which he recorded, as well as the operas of Richard Strauss and the symphonies of Schubert and Bruckner, which he played privately for his own pleasure.[33]

[edit] Eccentricities

Glenn Gould usually hummed while he played, and his recording engineers varied in how successfully they were able to exclude his voice from recordings. Gould claimed that his singing was subconscious and increased proportionately with the inability of the piano in question to realize the music as he intended. It is likely that this habit originated in Gould having been taught by his mother to 'sing everything that he played', as Kevin Bazzana puts it. This became 'an unbreakable (and notorious) habit'.[34] Some of Gould's recordings were severely criticised because of the background 'vocalise'. For example, a reviewer of his 1981 re-recording of the Goldberg Variations opined that many listeners would 'find the groans and croons intolerable'.[35] A similar habit is often exhibited by the jazz pianist Keith Jarrett.

Gould was renowned for his peculiar body movements while playing, (circular swaying, conducting, or grasping at the air as if to reach for notes as he did in the taping of Beethoven's Tempest Sonata) and for his insistence on absolute control over every aspect of his playing environment. The temperature of the recording studio had to be exactly regulated. He invariably insisted that it be extremely warm. According to Friedrich, the air conditioning engineer had to work just as hard as the recording engineers.[36] The piano had to be set at a certain height and would be raised on wooden blocks if necessary.[37] A small rug would sometimes be required for his feet underneath the piano.[38] He had to sit fourteen inches above the floor and would only play concerts while sitting on the old chair his father had made. He continued to use this chair even when the seat was completely worn through.[citation needed] His chair is so closely identified with him that it is shown in a place of honor in a glass case at the National Library of Canada.

Conductors responded diversely to Gould and his playing habits. George Szell, who led Gould in 1957 with the Cleveland Orchestra, remarked to his assistant, "That nut's a genius."[39] Leonard Bernstein said, "There is nobody quite like him, and I just love playing with him."[39] Ironically, Bernstein created a stir in April 1962 when just before the New York Philharmonic was to perform the Brahms D minor piano concerto with Gould as soloist, he informed the audience that he was assuming no responsibility for what they were about to hear. Specifically, he was referring to Gould's insistence that the entire first movement be played at half the indicated tempo. Plans for a studio recording of the performance came to nothing; the live radio broadcast (along with Bernstein's disclaimer) was subsequently released on CD.

Gould was averse to cold and wore heavy clothing, including gloves, even in warm places. He was once arrested, presumably mistaken for a vagrant, while sitting on a park bench in Sarasota, Florida, dressed in his standard all-climate attire of coat(s), warm hat and mittens.[40] He also disliked social functions. He had an aversion to being touched, and in later life he limited personal contact, relying on the telephone and letters for communication. Upon one visit to historic Steinway Hall in New York City in 1959, the chief piano technician at the time, William Hupfer, greeted Gould by giving him a slap on the back. Gould was shocked by this, and complained of aching, lack of coordination, and fatigue due to the incident; he even went on to explore the possibility of litigation against Steinway & Sons if his apparent injuries were permanent.[41] He was known for cancelling performances at the last minute, which is why Bernstein's above-mentioned public disclaimer opens with, "Don't be frightened, Mr. Gould is here; will appear in a moment."

In his liner notes and broadcasts, Gould created more than two dozen alter egos for satirical, humorous, or didactic purposes, permitting him to write hostile reviews or incomprehensible commentaries on his own performances. Probably the best known are the German musicologist "Karlheinz Klopweisser", the English conductor "Sir Nigel Twitt-Thornwaite", and the American critic "Theodore Slutz".[42]

Fran's Restaurant was a constant haunt of Gould's. A CBC profile noted, "sometime between two and three every morning Gould would go to Fran's, a 24-hour diner a block away from his Toronto apartment, sit in the same booth and order the same meal of scrambled eggs."[43]

[edit] Philosophical and aesthetic views

Gould stated that had he not been a musician, he would have been a writer. He wrote music criticism and expounded his philosophy of music and art, in which he rejected what he deemed banal in music composition and its consumption by the public. In seeming contrast to his geniality, open-mindedness and modernism, Gould's remarks on jazz and other popular music were mostly uninterested or oblique. He enjoyed a jazz concert with his friends as a youth, mentioned jazz in his writings, and once criticized The Beatles for "bad voice leading[44]". He did, however, share a mutual admiration with jazz pianist Bill Evans, who made his seminal record "Conversations With Myself" using Gould's celebrated Steinway CD 318 piano. He believed that the keyboard is fulfilled as an instrument primarily through counterpoint, a musical style which reached its zenith during the Baroque era. Much of the homophony that followed, he felt, belongs to a less serious and less spiritual period of art.

Gould was convinced that the institution of the public concert with audience en masse and the tradition of applause was a force of evil, and that these practices should be abandoned. This doctrine he set forth, half in jest and half seriously, in "GPAADAK," the Gould Plan for the Abolition of Applause and Demonstrations of All Kinds.[45]

Gould enjoyed solitude, and expressed that theme in his trio of radio documentaries, the Solitude Trilogy.

Having entertained a life-long fascination with the hereafter, with theories of reincarnation and mystic numerology akin to those of Arnold Schoenberg, Gould believed that he would be reincarnated two years after his death in the person of Sam Caldwell, a media theorist and contrapuntal poet. This belief was strengthened by Gould's regrets, expressed particularly in his 1980 interviews with Bruno Monsaigneon, that he had not brought his contrapuntal radio work to a satisfactory stage of completion. With plans to explore to its logical conclusion the application of Wagnerian leitmotifs and J.S. Bach's contrapuntal textures in the medium of the spoken word, and particularly in poetry, Gould conceived of this fictional 'second go around,' toward the end of his already immensely productive lifetime.

[edit] Health

Early in his life Gould suffered a spine injury which prompted his physicians to prescribe him an assortment of painkillers and other drugs. Some speculate that his continued use of prescribed medications throughout his career had a deleterious effect on his health. He was highly concerned about his health throughout his life, worrying about everything from high blood pressure, to the safety of his hands. It is often claimed that Gould never shook hands with anyone and always wore gloves.[46] However, there are documented cases of Gould shaking hands.[47]

Gould's experience with psychoanalytic treatment and medication is well documented. After his death, Dr. Timothy Maloney, director of the Music Division of the National Library of Canada, wrote about the possibility that Gould also had Asperger's syndrome,[48] commonly referred to as a high-functioning type of autism first described in a medical paper in 1981. This idea was first tentatively proposed by Gould's biographer, Dr. Peter Ostwald, who argued that Gould's eccentricities, such as rocking and humming, isolation and difficulty with social interaction, dislike of being touched, and uncanny focus and technical ability, can be related to the symptoms displayed by persons with Asperger's, according to Maloney. Ostwald died before he could further develop his theory. However, other experts dismiss this theory as post-mortem diagnosis based on circumstantial evidence.[49] Dr. Helen Mesaros, a Toronto psychiatrist and author, published a rebuttal to Maloney's paper suggesting that there are ample psychological and emotional explanations for Gould's eccentricities, and that it is not necessary to resort to neurological explanations.

[edit] Relationships

Gould lived a private life: Yehudi Menuhin said of him, "No supreme pianist has ever given of his heart and mind so overwhelmingly while showing himself so sparingly."[citation needed]

In 2007, Cornelia Foss, wife of composer and conductor Lukas Foss, publicly revealed in an article in the Toronto Star (August 25, 2007) that she and Gould had had a love affair lasting several years. She and her husband had met Gould in Los Angeles in 1956. Cornelia was an art instructor who had studied sculpture at the American Academy in Rome; Lukas was a pianist and composer who conducted both the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra and the Brooklyn Philharmonic.

After several years, Glenn and Cornelia became lovers. Cornelia left Lukas in 1967 for Gould, taking her two children with her to Toronto, where she purchased a house near Gould's apartment at 110 St. Clair Avenue West. According to Cornelia, "There were a lot of misconceptions about Glenn and it was partly because he was so very private. But I assure you, he was an extremely heterosexual man. Our relationship was, among other things, quite sexual." Their affair lasted until 1972, when she returned to Lukas. As early as two weeks after leaving her husband, she had noticed disturbing signs in Gould. She describes a serious paranoid episode:

"It lasted several hours and then I knew he was not just neurotic — there was more to it. I thought to myself, `Good grief, am I going to bring up my children in this environment?' But I stayed four and a half years." Foss did not discuss details, but others close to Gould said he was convinced someone was trying to poison him and that others were spying on him.[50]

[edit] Awards and recognitions

Glenn Gould received many honors before and after his death, although he personally claimed to despise competition in music. In 1983, he was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame.

- The Glenn Gould Foundation was established in Toronto in 1983 to honour Gould and preserve his memory. Among other activities, the foundation awards the Glenn Gould Prize every three years to "an individual who has earned international recognition as the result of a highly exceptional contribution to music and its communication, through the use of any communications technologies." The prize consists of CAD$50,000 and an original work by a Canadian artist.

- The Glenn Gould School of the Royal Conservatory of Music was founded and named after him in 1997.[51]

- The Glenn Gould Studio at the Canadian Broadcasting Centre in Toronto was named after him.

Gould won four Grammy Awards:

- 1974 — Grammy Award for Best Album Notes - Classical: Glenn Gould (notes writer) for Hindemith: Sonatas for Piano (Complete) performed by Glenn Gould;

- 1983 — Grammy Award for Best Classical Album: Samuel H. Carter (producer) & Glenn Gould for Bach: The Goldberg Variations;

- 1983 — Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) for Bach: The Goldberg Variations;

- 1984 — Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) for Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 12 & 13.

[edit] Works by and about Gould

[edit] Musical Works

- Louie, Alexina (1982) O Magnum Mysterium: In Memoriam Glenn Gould. For string orchestra.

[edit] Books

- Andreacchi, Grace (2007) Scarabocchio A novel in which a lightly fictionalized Glenn Gould plays a prominent part.

- Bazzana, Kevin (1997) Glenn Gould: the performer in the work. Clarendon, ISBN 0-19-816656-7

- Bazzana, Kevin (2003) Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-517440-2

- Bernhard, Thomas (1991) The Loser. A fictional account of a relationship with Glenn Gould and Vladimir Horowitz. University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-04388-6

- Canning, Nancy (1992) A Glenn Gould Catalog. Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-27412-6

- Carroll, Jock (1995) Glenn Gould: some portraits of the artist as a young man. Stoddart, ISBN 0-7737-2904-6

- Cott, Jonathan (2005) Conversations with Glenn Gould. University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-11623-9. Interview in two parts from 1974. Originally published in Rolling Stone magazine.

- Friedrich, Otto (1989) Glenn Gould: A Life and Variations. Random House, ISBN 0-679-73207-1

- Hafner, Katie (2008) A Romance on Three Legs: Glenn Gould's Obsessive Quest for the Perfect Piano. McClelland & Stewart, ISBN 0-7710-3754-6

- Kazdin, Andrew (1989) Glenn Gould at Work: Creative Lying. E.P. Dutton, ISBN 0-525-24817-X

- Mesaros, Helen M.D. (2008) Bravo Fortissimo: Glenn Gould The Mind of a Canadian Virtuoso. American Literary Press Inc., ISBN 1-5616-7985-2

- National Library of Canada (1992) Descriptive Catalogue of the Glenn Gould Papers. ISBN 0-660-57327-X

- Ostwald, Peter (1997) Glenn Gould: the ecstasy and tragedy of genius. Norton, ISBN 0-393-04077-1

- Page, Tim (1984) The Glenn Gould Reader. Contains a select collection of Gould's essays, articles and liner notes. Knopf, ISBN 0-394-54067-0

- Payzant, Geoffrey (1992) Glenn Gould Music and Mind. Key Porter, ISBN 1-55013-439-6

- Rieger, Stefan (1997) Glenn Gould czyli sztuka fugi. Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, ISBN 978-83-7453-834-3

- Robert, John PL and Ghyslaine Guertin (1992) Glenn Gould : selected letters. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-540799-7

- Rosen, Charles (2002) Piano Notes: The World of the Pianist. The Free Press, ISBN 0-7432-4312-9.

[edit] Films about Gould

- Glenn Gould On the Record and Glenn Gould Off the Record (both 1959). Documentaries. National Film Board of Canada.

- Glenn Gould (1961). Biography by the NFB.

- Conversations with Glenn Gould (1966). Filmed conversations between Glenn Gould and Humphrey Burton on classical composers. BBC.

- The Idea of North (film)(1970) Produced and directed by Judith Pearlman; based on Gould's original audio version.

- Music and Terminology, Chemins de la Musique (1973-76). Glenn Gould talking about and performing music by Bach, Schoenberg, Scriabin, Gibbons, Byrd, Berg, and Wagner. Series of four films directed by Bruno Monsaingeon.

- Radio as Music (1975). Film adaptation of an article by John Jessop (in collaboration with Gould) on Glenn Gould's contrapuntal radio documentary techniques.

- Bach Series (1979-91). Series of three films of Glenn Gould talking about and performing the music of Bach: Goldberg Variations, Variations: Chromatic Fantasy, Partita No 4, and excerpts from The Well-Tempered Clavier and Art of the Fugue. Clasart.

- The Goldberg Variations: Glenn Gould Plays Bach (1981). The Bach Series directed by Bruno Monsaingeon.

- Variations on Glenn Gould. Documentary on Glenn Gould at a recording session, making a radio documentary and in the Ontario northland.

- Solitude, Exile and Ecstasy was a BBC Radio 3 drama broadcast in 1991. It features Gould as a character, and is structured by sequential selections from his 1981 performance of JS Bach's Goldberg Variations.[52]

- Les Variacions Gould (1992). Directed by Manuel Huerga, documentary coproduced by Ovideo TV about Glenn Gould in the 10th anniversary of his death. This film has received several awards and has been finalist in the International Visual Music Awards of Cannes '93.

- Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993). Directed by François Girard and starring Colm Feore as Gould.

- Glenn Gould : The Russian Journey (2002). The 1957 trip in the USSR and Gould's performances in Moscow and Leningrad.

- Extasis (2003). Documentary featuring Glenn Gould in concert; also, interviews with acquaintances.

- Glenn Gould : Life & Times (2003). DVD documentary. Contains performances, sessions and interviews. Also a look at his [still-playable] grand piano and chair.

- Glenn Gould : The Alchemist (2003). DVD documentary footage of Gould's performances and interviews with Gould about his music and life.

- Glenn Gould : au-delà du temps (2005). A French/Canadian documentary by Bruno Monsaingeon, 107 minutes, first aired on arte, May 13, 2006, Winner of Fipa d’or 2006, catégorie musique et spectacles.

- Gould contributed to the screenplay of the experimental PBS TV movie The Idea of North, produced and directed by Judith Pearlman.

[edit] Films using Gould's music

Gould's recorded music has been featured in many other films, both in his lifetime and after his death.

- Spheres (1969). Animated film directed by René Jodoin and Norman McLaren, with music by Bach played by Glenn Gould. National Film Board of Canada.

- Slaughterhouse-Five (1972). Directed by George Roy Hill; based on the Kurt Vonnegut novel. Musical soundtrack arranged and performed by Glenn Gould. Universal Pictures.

- The Terminal Man (1974). Directed by Mike Hodges; based on a Michael Crichton novel. Soundtrack features Glenn Gould playing the Goldberg Variations. Warner Bros.

- The Wars (1983) features Gould playing music of Richard Strauss and Johannes Brahms. Directed by Robin Philips; based on the novel by Timothy Findley.

- Hannibal (2001) uses Gould's 1981 recording of the Goldberg Variations.

- The Triplets of Belleville (2003) includes a segment in which an animated Glenn Gould with greatly exaggerated mannerisms plays Prelude No. 2 in C minor from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One.

- Gould's prowess was referenced (and his recordings used) in the motion picture When Will I Be Loved, written and directed by James Toback.

- Hannibal Rising (2007) has a scene in which the young Hannibal Lecter plays Gould's 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations while he injects himself with sodium thiopental. This is an anachronism, because the scene takes place when Lecter is an eighteen-year-old medical student in Paris in 1951.[53] In The Silence of the Lambs, Lecter listens to a recording of the variations while incarcerated in the United States, but the movie uses a recording by Jerry Zimmermann, not Gould.

[edit] Published music

- Cadenza to Beethoven Concerto No.1, Op.15 (Barger and Barclay)

- Piano Pieces ISMN: M-001-08466-6 (Schott)

- String Quartet Op. 1 (Barger and Barclay ed., 1956)

- String Quartet Op. 1 ISMN: M-001-12171-2 (Schott ed.)

- Lieberson Madrigal (SATB and Piano) ISMN: M-001-11577-3 (Schott)

- So You Want To Write A Fugue? (G. Schirmer)

- Sonata for Piano ISMN: M-001-13363-0 (Schott)

- Sonata for Bassoon and Piano ISMN: M-001-09317-0 (Schott)

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b c 'Gould's first name is frequently misspelled as "Glen" in documents (including official ones) dating back to the beginning of his life, and Gould himself used both spellings interchangeably throughout his life.' - Bazzana, 2003, p.27. Bazzana further investigated the name-change records in Ontario's Office of the Registrar General and found only a record of his father Bert's name-change to Gould in 1979 (to be able to legally marry with that name); he concludes that the family's name-change was informal and 'Gould was still legally 'Glenn Herbert Gold' when he died.'

- ^ a b c 'his birth certificate gave his name as "Gold, Glenn Herbert." The family name had always been Gold [...] All of the documents through 1938 that survive among Gould's papers give his surname as "Gold," but beginning at least as early as June 1939 the family name was almost always printed "Gould" in newspapers, programs, and other sources; the last confirmed publication of "Gold" is in the program for a church supper and concert on October 27, 1940. The whole family adopted the new surname' - Bazzana, 2003, p.24.

- ^ Bazzana, 2003, p.21

- ^ Bazzana, 2003, p.30

- ^ Full circumstances of the name-change are in Bazzana, 2003, p.24-26

- ^ 'At least as far back as the mid-eighteenth century there were no Jews in this particular Gold lineage.' - Bazzana, 2003, p.27

- ^ Quoted in Bazzana, 2003, p.24

- ^ Friedrich, 1990, p.15.

- ^ Bert Gould, cited in Friedrich, Otto, Glenn Gould, A Life and Variations, Lime Tree, 1990, p.15.

- ^ Ostwald 1997, p. 48 refers to a concert at this location on December 9, 1938 at which Gould performed a 'piano composition'.

- ^ Bazzana 2003, 229.

- ^ Bazzana, 2003, p.352-368. Bazzana uses a quote from Gould as a heading: "They say I'm a hypochondriac, and, of course, I am."

- ^ "no physical abnormalities were found in the kidneys, prostate, bones, joints, muscles, or other parts of the body that Glenn so often had complained about." - Bazzana, 2003, p.190, quoting Ostwald

- ^ Ostwald, pages 325 - 328

- ^ He did this in music of medium to very slow tempo. The clockwise motion is associated with left-handedness (Theodore H. Blau, The torque test: A measurement of cerebral dominance. 1974, American Psychological Association) and rather than mental abnormality suggests a musical function.

- ^ Friedrich, 1990, p. 27. Otto Friedrich dates this incident on the basis of discussion with Gould's father, who is cited by Friedrich as stating that it occurred 'when the boy was about ten'.

- ^ Ostwald 1997, p. 71

- ^ Ostwald 1997, p.73

- ^ In outtakes of the Goldberg Variations, Gould describes clearly his practicing technique by composing a drill on Variation 11, remarking that he is "still sloppy" and with his usual humor that "a little practicing is in order." He is also heard practicing other parts of the Goldbergs. Of earlier years it was recalled that "he would not come out [away from the piano] until he knew it" (of one of Beethoven's piano concertos, from a biographical documentary).

- ^ Interview with Gould by David Dubal in "The World of the Concert Pianist", p180-83. There are recordings of Gould practicing, but to what extent he did is difficult to determine.

- ^ From the liner notes to Bach Partitas, Preludes and Fugues, page 15: Sony CD SM2K-52597.

- ^ "Glenn Gould, Biography". Sony BMG Masterworks. Archived from the original on 2008-02-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20080210175113/http://www.sonyclassical.com/artists/gould/bio.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ Friedrich, 1990, p.147.

- ^ Friedrich, 1990, p.100.

- ^ Gould, Glenn (1966). "The Prospects of Recording - Resources - The Glenn Gould Archive". Library and Archives Canada. http://www.collectionscanada.ca/glenngould/028010-502.1-e.html#d. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ "Of Mozart and Related Matters. Glenn Gould in Conversation with Bruno Monsaingeon", Piano Quarterly Fall 1976. Reprinted in Page (1990), page 33. See also Ostwald page 249.

- ^ Ostwald 1997, 249.

- ^ He discusses this on the Bruno Monsaingeon film 'Chemins de la Musique'.

- ^ "Voyager - Music From Earth". NASA. http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/spacecraft/music.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ a b c Gould Meets Menuhin, Sony Classical, SMK 52688, 1993

- ^ Sony Classical, Richard Strauss, Ophelia-Lieder, et al, SM2K 52657, 1992, Liner Notes, p.12

- ^ CBC's Dan Bjarnason reports on newly discovered film of Glenn Gould's live television performance for the Queen's 1957 visit to Canada (Runs 3:24). It also contained footage of a Quodlibet including the Star-Spangled Banner and God Save the Queen.

- ^ The Schubert can be seen briefly on Hereafter, the transcription of Bruckner's 8th symphony Gould alludes to in an article in The Glenn Gould Reader where he deprecates its "sheer leger-line unplayability"; the Strauss opera playing can be seen in one of the Humphrey Burton conversations and is referred to by almost everyone who saw him play in private.

- ^ Bazzana, 2003, p.47.

- ^ Greenfield, E., Layton, R., & March, I., The New Penguin Guide to Compact Discs and Cassettes, Penguin, 1988, p.44.

- ^ Friedrich, 1990, p.50.

- ^ Ostwald 1997, p. 18

- ^ Friedrich, 1990, p.51

- ^ a b Bazzana 2003, p. 158.

- ^ Friedrich, 62.

- ^ "Musician's Medical Maladies". Arizona Health Sciences Library. Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. http://web.archive.org/web/20071230140202/http://www.ahsl.arizona.edu/about/ahslexhibits/musicianmedicalmaladies/musicians.cfm. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ From the liner notes to Bach Partitas, Preludes and Fugues, page 14: Sony CD SM2K-52597.

- ^ "Glenn Gould: Variations on an Artist". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. http://archives.cbc.ca/IDC-1-68-320-1673/arts_entertainment/glenn_gould/. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ These comments can be found in essays in The Glenn Gould Reader.

- ^ Gould, Glenn. The Glenn Gould Reader. ISBN 0-5711-4852-2.

- ^ This is discussed and can be seen on the film On And Off The Record.

- ^ Friedrich, 267. Interview of Timothy Findley: "[...]Everybody said you never touched his hands, you never try to shake hands with him, but the first thing he did to me was to offer to shake hands. He offered me his hand in a very definite way, none of this tentative, 'don't-touch-me' stuff."

- ^ see Timothy Maloney, "Glenn Gould, Autistic Savant," in Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music, edited by Neil Lerner & Joseph Straus (New York: Routledge, 2006, pp. 121-135 (Chapter 9).

- ^ 'So far I have not been persuaded that such a diagnosis [Ostwald and Maloney's suggestions of Asperger's] really fits the biographical facts or is necessary for making sense of Gould. - Bazzana, 2003, p.5

- ^ Toronto Star, August 25, 2007.

- ^ "The Glenn Gould School". Royal Conservatory of Music. http://www.rcmusic.ca/ContentPage.aspx?name=glennGould. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ Charlton, Bruce. "Solitude, Exile and Ecstasy". BBC. http://www.hedweb.com/bgcharlton/solitude.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-12.

- ^ In the novel, Hannibal is an eight-year old in 1941 (p.5). At eighteen (p.163) he is the youngest medical student in French history, the age at which the injection scene occurs. The book makes no mention of the Goldberg Variations, however. During this scene Lecter plays a 'scratchy record' of 'children's songs' on a 'wind-up phonograph' (p.197). The film closely follows the novel's chronology, or at least attempts to. (Page references are to the 2006 William Heinemann edition).

[edit] References

- Bazzana, Kevin (2004). Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0195174402.

- Friedrich, Otto (1989) Glenn Gould: A Life and Variations. Random House, ISBN 0-679-73207-1

- Ostwald, Peter (1997) Glenn Gould: The Ecstasy and Tragedy of Genius. Norton, ISBN 0-393-04077-1

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Glenn Gould |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Glenn Gould |

- The Glenn Gould Foundation

- The Glenn Gould Archive at the National Library of Canada - Contains sound clips, articles and pictures.

- Sarabande - The Glenn Gould Project

- Glenn Gould Website (Sony Music Entertainment of Canada)

- Bach-cantatas.com: Glenn Gould

- GlennGould Magazine

- CBC Digital Archives: Glenn Gould: Variations on an Artist

- Glenn Gould Broadcasts from UbuWeb.

- The Idea of North, the PBS film produced and directed by Judith Pearlman, based on Gould's original audio version.

- Report about newly discovered film of a Glenn Gould television performance for the Queen's 1957 visit to Canada

- "Music, McLuhan, Modality: Musical Experience from 'Extreme Experience' to 'Alchemy'" By Deanne Bogdan, in MediaTropes eJournal, www.mediatropes.com, vol. 1 (2008): 71-101. This article reflects on "musical information literacy" and Glenn Gould's relation with media guru Marshall McLuhan.