Toxoplasma gondii

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Toxoplasma gondii | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

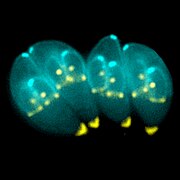

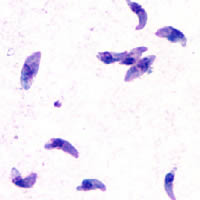

T. gondii tachyzoites

|

||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||

| Toxoplasma gondii (Nicolle & Manceaux, 1908) |

Toxoplasma gondii is a species of parasitic protozoa in the genus Toxoplasma.[1] The definitive host of T. gondii is the cat, but the parasite can be carried by all known mammals. Toxoplasmosis, the disease of which T. gondii is the causative agent, is usually minor and self-limiting but can have serious or even fatal effects on a fetus whose mother first contracts the disease during pregnancy or on an immunocompromised human or cat. Preventing toxoplasmosis during pregnancy involves avoiding eating undercooked or cured meat, thoroughly washing fruit and vegetables before eating, and avoiding soil contact. If gardening, wear protective rubber gloves and wash hands thoroughly afterwards. Avoidance of cats is commonly recommended to uninfected pregnant women,[2] but the contribution of this risk factor is controversial.[3] Some studies have identified cat ownership or contact as a minor source of risk,[4] while several other major studies have failed to identify exposure to cats as a significant risk factor for Toxoplasma infection [5][6].

Contents |

[edit] Life cycle

The life cycle of T. gondii has two phases. The sexual part of the life cycle (coccidia like) takes place only in members of the Felidae family (domestic and wild cats), which makes these animals the parasite's primary host. The asexual part of the life cycle can take place in any warm-blooded animal, like other mammals (including felines) and birds.

In the intermediate hosts (as well the definitive host, felines), the parasite invades cells, forming intracellular so-called parasitophorous vacuoles containing bradyzoites, the slowly replicating form of the parasite.[7] Vacuoles form tissue cysts mainly within the muscles and brain. Since they are within cells, the host's immune system does not detect these cysts. Resistance to antibiotics varies, but the cysts are very difficult to eradicate entirely. Within these vacuoles T. gondii propagates by a series of binary fissions until the infected cell eventually bursts and tachyzoites are released. Tachyzoites are the motile, asexually reproducing form of the parasite. Unlike the bradyzoites, the free tachyzoites are usually efficiently cleared by the host's immune response, although some manage to infect cells and form bradyzoites, thus maintaining the infection.

Tissue cysts are ingested by a cat (e.g., by feeding on an infected mouse). The cysts survive passage through the stomach of the cat and the parasites infect epithelial cells of the small intestine where they undergo sexual reproduction and oocyst formation. Oocysts are shed with the feces. Animals and humans that ingest oocysts (e.g., by eating unwashed vegetables etc.) or tissue cysts in improperly cooked meat become infected. The parasite enters macrophages in the intestinal lining and is distributed via the blood stream throughout the body.

Acute stage Toxoplasma infections can be asymptomatic, but often give flu-like symptoms in the early acute stages, and like flu can become, in very rare cases, fatal. The acute stage fades in a few days to months, leading to the latent stage. Latent infection is normally asymptomatic; however, in the case of immunocompromised patients (such as those infected with HIV or transplant recipients on immunosuppressive therapy), toxoplasmosis can develop. The most notable manifestation of toxoplasmosis in immunocompromised patients is toxoplasmic encephalitis, which can be deadly. If infection with T. gondii occurs for the first time during pregnancy, the parasite can cross the placenta, possibly leading to hydrocephalus or microcephaly, intracranial calcification, and chorioretinitis, with the possibility of spontaneous abortion (miscarriage) or intrauterine death.

[edit] Toxoplasmosis

T. gondii infections have the ability to change the behavior of rats and mice, making them drawn to rather than fearful of the scent of cats. This effect is advantageous to the parasite, which will be able to sexually reproduce if its host is eaten by a cat. [8] The infection is almost surgical in its precision, as it does not affect a rat's other fears such as the fear of open spaces or of unfamiliar smelling food. There has been speculation that human behavior may also be affected in some ways, and correlations have been found between latent Toxoplasma infections and various characteristics such as decreased novelty-seeking behavior, slower reactions, feelings of insecurity, and neuroticism.[9]

Several independent pieces of evidence point towards a possible role of Toxoplasma infection in some cases of schizophrenia and paranoia, but this theory does not seem to account for many cases.[10] A recent study has indicated toxoplasmosis is also correlated strongly with an increase in boy births in humans, leading to an alteration of the human sex ratio.[11] According to the researchers, "depending on the antibody concentration, the probability of the birth of a boy can increase up to a value of 0.72 " The study also notes a mean rate of 0.60 to 0.65 (as opposed to the normal 0.51) for Toxoplasma positive mothers.

One study suggests that a possible behavior modification is that people not infected with the parasite found women with toxoplasma more attractive than women who don't have toxoplasma.[12] Another study performed in the Czech Republic suggests individuals with latent toxoplasmosis had a 2.65 times higher risk of traffic accidents than noninfected subjects; and concludes "that 'asymptomatic' acquired toxoplasmosis might in fact represent a serious and highly underestimated public health problem, as well as an economic problem."[13]

The prevalence of human infection by Toxoplasma varies greatly between countries. Factors that influence infection rates include diet (prevalence is possibly higher where there is a preference for less-cooked meat) and proximity to cats.

[edit] History

The organism was first described in 1908 in Tunis by Nicolle and Manceaux within the tissues of the gundi (Ctenodactylus gundi). In the same year it was also described in Brazil by Splendore in rabbits .

[edit] References

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (eds) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed. ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 722–7. ISBN 0838585299.

- ^ American Academy of Family Physicians (2005). "Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy". AAFP. http://familydoctor.org/online/famdocen/home/women/pregnancy/illness/180.printerview.html.

- ^ Kravetz JD, Federman DG (March 2005). "Toxoplasmosis in pregnancy". Am. J. Med. 118 (3): 212–6. doi:. PMID 15745715. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002-9343(04)00700-4.

- ^ Lopez A, Dietz VJ, Wilson M, Navin TR, Jones JL (March 2000). "Preventing congenital toxoplasmosis". MMWR Recomm Rep 49 (RR-2): 59–68. PMID 15580732. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr4902a5.htm.

- ^ Cook AJ, Gilbert RE, Buffolano W, et al (July 2000). "Sources of toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: European multicentre case-control study. European Research Network on Congenital Toxoplasmosis". BMJ 321 (7254): 142–7. doi:. PMID 10894691. PMC: 27431. http://bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10894691.

- ^ Bobić B, Jevremović I, Marinković J, Sibalić D, Djurković-Djaković O. (1998). "Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in a reproductive age female population in the area of Belgrade, Yugoslavia". Eur J Epidemiol.. 14: 605. doi:. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9794128.

- ^ Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Speer CA (1998). "Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11 (2): 267–99. PMID 9564564. http://cmr.asm.org/cgi/content/full/11/2/267?view=long&pmid=9564564.

- ^ Berdoy M, Webster JP, Macdonald DW (August 2000). "Fatal attraction in rats infected with Toxoplasma gondii". Proc. Biol. Sci. 267 (1452): 1591–4. doi:. PMID 11007336. PMC: 1690701. http://journals.royalsociety.org/openurl.asp?genre=article&issn=0962-8452&volume=267&issue=1452&spage=1591.

- ^ Carl Zimmer, The Loom. A Nation of Neurotics? Blame the Puppet Masters?, 1 Aug. 2006

- ^ Torrey EF, Yolken RH (2003). "Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia". Emerging Infect. Dis. 9 (11): 1375–80. PMID 14725265. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/EID/vol9no11/03-0143.htm.

- ^ Flegr J (2006). "Women infected with parasite Toxoplasma have more sons" (PDF). Naturwissenschaften. http://www.natur.cuni.cz/~flegr/pdf/toxosons.pdf.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (2000). Parasite Rex : Inside the Bizarre World of Nature's Most Dangerous Creatures. Free Press. ISBN 074320011X.

- ^ Flegr J, Havlicek J, Kodym P, Maly M, Smahel Z (Jul 2002). "Increased risk of traffic accidents in subjects with latent toxoplasmosis: a retrospective case-control study.". BMC Infectious Diseases 2: 11. doi:. PMID 12095427. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/2/11.

[edit] External links

- ToxoDB : The Toxoplasma gondii genome resource

- Anti-Toxo : A Toxoplasma news blog and list of research laboratories

- Toxoplasma images, from CDC's DPDx, in the public domain

- Toxoplasmosis Research Institute & Center

- Cytoskeletal Components of an Invasion Machine — The Apical Complex of Toxoplasma gondii

- The Culture-Shaping Parasites, in Seed Magazine

- Sneaky Parasite Attracts Rats to Cats, All Things Considered, April 14, 2007

- Toxoplasma overview, developmental stages, life cycle image at MetaPathogen

- Toxoplasma lecture, Robert Sapolsky