Mata Hari

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

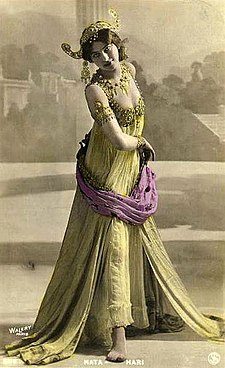

| Mata Hari | |

Mata Hari, exotic dancer and convicted spy, made her name synonymous with femme fatale during World War I.

|

|

| Born | Margaretha Geertruida Zelle 7 August 1876 Leeuwarden, the Netherlands |

|---|---|

| Died | 15 October 1917 (aged 41) Vincennes, France |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Nationality | Dutch-Frisian |

| Children | 2 |

Mata Hari was the stage name of Margaretha Geertruida "Grietje" Zelle (7 August 1876, Leeuwarden – 15 October 1917, Vincennes), a Dutch-Frisian exotic dancer and courtesan who was executed by firing squad for espionage during World War I.[1]

Contents |

[edit] Early life

Margaretha Zelle was born in Leeuwarden, Friesland in the Netherlands, as the first daughter and child among the four children of Adam Zelle (Leeuwarden, 2 October 1840 - Amsterdam, 13 March 1910) and first wife (m. Franeker, 4 June 1873) Antje van der Meulen (Franeker, 21 April 1842 - Leeuwarden, 9 May 1891), both born and raised in Friesland.[2] She had two brothers and one sister: Johannes Henderikus Zelle (b. Leeuwarden, 26 November 1878), Cornelis Coenraad Zelle (Leeuwarden, 9 August 1881 - Amsterdam, 31 May 1956) and Arie Anne Zelle (b. Leeuwarden, 6 May 1885). Adam owned a hat store, had made successful investments in the oil industry and became affluent enough to give Margaretha a lavish early childhood.[3] Thus, Margaretha attended only exclusive upper class schools until age 13.[4] However, Margaretha's father went bankrupt in 1889, her parents divorced soon afterwards, and Margaretha's mother died in 1891.[3][4] Her father remarried in Amsterdam on 9 February 1893 Susanna Catharina ten Hoove (Amsterdam, 11 March 1844 - Amsterdam, 1 December 1913), by whom he had no issue. The family had come apart and she moved to live with her godfather, Heer Visser, at Sneek. At Leiden, she studied to be a kindergarten teacher but when the headmaster began to flirt with her conspicuously, she was sent from the institution by her offended godfather. [5][3][4] After only a few months she fled to her uncle's home in The Hague.[5]

[edit] Indonesia

At 18, she answered an advertisement in a Dutch newspaper placed by a man looking for a wife. Margaretha married Dutch Colonial Army officer Rudolf John MacLeod (Heukelum, 1 March 1856 - Velp, 9 January 1928) in Amsterdam on 11 July 1895. He was the son of John Brienen MacLeod (Kampen, 11 February 1825 - Millingen aan de Rijn, 1868) and wife (m. Nijmegen, 27 September 1856) Dina Louisa Frijherrine Sweerts de Landas (Gorinchem, 12 March 1831 - Haarlem, 27 May 1901). They moved to Java (Dutch East Indies) and had two children, Norman-John (Amsterdam, 30 January 1897 - 27 June 1899) and Jeanne-Louise (Java, 2 May 1898 - 10 August 1919).

The marriage was an overall disappointment. [6] MacLeod was a violent alcoholic who would take out his frustrations on his wife, who was half his age, and whom he blamed for his lack of promotion. He also openly kept both a native wife and a concubine. The disenchanted Margaretha abandoned him temporarily, moving in with Van Rheedes, who was another Dutch officer. For months she studied the Indonesian traditions intensively, joining a local dance company. In 1897, she revealed her artistic surname Mata Hari, Malay for "eye of the day" or the sun, via correspondence to her relatives in Holland.[4]

At MacLeod's urging, Margaretha returned to him although his aggressive demeanour hadn't changed. She escaped her circumstances by studying the local culture.[4] Their son Norman died in 1899 possibly of complications relating to the treatment of syphilis contracted from his parents, though the family claimed he was poisoned by an irate servant. Some sources[4] maintain that one of Rudolf's enemies may have poisoned a supper to kill both of their children (Norman and Jeanne-Louise). After moving back to the Netherlands, the couple divorced in 1903, with Rudolf forcibly retaining the custody of his daughter (who later died at the age of 21, also possibly from complications relating to syphilis).[7]

Her husband later married secondly in Rheden on 22 November 1907 Elisabeth Martina Christina van der Mast (b. Gorinchem, ca. 1880) and thirdly Grietje Meijer (b. Warffum, ca. 1892).

[edit] Paris

In 1903, Margaretha moved to Paris, where she performed as a circus horse rider, using the name Lady MacLeod. Struggling to earn a living, she also posed as an artist's model.

By 1905, she began to win fame as an exotic dancer. It was then that she adopted the stage name Mata Hari. She was a contemporary of dancers Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, leaders in the early modern dance movement, which around the turn of the 20th century looked to Asia and Egypt for artistic inspiration. Critics would later write about this and other such movements within the context of orientalism. Gabriel Astruc became her personal booking agent.[4]

Promiscuous, flirtatious, and openly flaunting her body with a mystique that captivated both her audiences and the public, Mata Hari was an overnight success from the debut of her act at the Musée Guimet on 13 March 1905.[8] Following that success, she became the long-time mistress of the millionaire Lyon industrialist Emile Etienne Guimet who founded the Musée. She posed as a Java princess of priestly Hindu birth, pretending to have been immersed in the art of sacred Indian dance since childhood. She was photographed numerous times during this period, nude or nearly so. Some of these pictures were obtained by MacLeod and strengthened his case in keeping custody of their daughter.

She brought this carefree provocative style to the stage in her act, which garnered wide acclaim. The most celebrated segment of her act was her progressive shedding of clothing until she wore just a jeweled bra and some ornaments upon her arms and head.[4] She was seldom seen without a bra as she was self-conscious about being small-breasted.

Although the explanations and claims made by her about her origins were fictitious, the act was spectacularly successful because it elevated exotic dance to a more respectable status, and so broke new ground in a style of entertainment for which Paris was later to become world famous. Her style and her free-willed attitude made her a very popular woman, as did her eagerness to perform in exotic and revealing clothing. She posed for provocative photos and mingled in wealthy circles. At the time, as most Europeans were unfamiliar with the Dutch East Indies and thus thought of Mata Hari as exotic, it was assumed her claims were genuine.

By approximately 1910, myriad imitators had arisen. Critics began to opine that the success and dazzling features of the popular Mata Hari was due to cheap exhibitionism, lacking artistic attributes. Although she continued to schedule important social events throughout Europe, she was disdained by serious cultural institutions as a dancer who did not know how to dance.[4]

Mata Hari was also a successful courtesan, though she was known more for her sensuality and eroticism rather than for striking classical beauty. She had relationships with high-ranking military officers, politicians, and others in influential positions in many countries, including the German crown prince,[citation needed] who paid for her luxurious lifestyle.

Her relationships and liaisons with powerful men frequently took her across international borders. Prior to World War I, she was generally viewed as an artiste and a free-spirited bohemian, but as war approached, she began to be seen by some as a wanton and promiscuous woman, and perhaps a dangerous seductress.

[edit] Double agent

During World War I, the Netherlands remained neutral. As a Dutch subject, Margaretha Zelle was thus able to cross national borders freely. To avoid the battlefields, she travelled between France and the Netherlands via Spain and Britain, and her movements inevitably attracted attention. She was a courtesan to many high-ranking allied military officers during this time.[citation needed] On one occasion, when interviewed by British intelligence officers, she admitted to working as an agent for French military intelligence, although the latter would not confirm her story. It is unclear if she lied on this occasion, believing the story made her sound more intriguing, or if French authorities were using her in such a way, but would not acknowledge her due to the embarrassment and international backlash it could cause.

In January 1917, the German military attaché in Madrid transmitted radio messages to Berlin describing the helpful activities of a German spy, code-named H-21. French intelligence agents intercepted the messages and, from the information they contained, identified H-21 as Mata Hari. Unusually, the messages were in a code that German intelligence knew had already been broken by the French, leaving some historians to suspect that the messages were contrived.

[edit] Case

On 13 February 1917, Mata Hari was arrested in her hotel room at Hotel Plaza Athénée in Paris. She was put on trial, accused of spying for Germany and consequently causing the deaths of at least 50,000 soldiers. She was found guilty and was executed by firing squad on 15 October 1917, at the age of 41.

Pat Shipman's biography Femme Fatale argues that Mata Hari was never a double agent, speculating that she was used as a scapegoat by the head of French counter-espionage. Georges Ladoux had been responsible for recruiting Mata Hari as a French spy and later was arrested for being a double agent himself. The facts of the case remain vague, because the official case documents regarding the execution were sealed for 100 years.

[edit] Execution eyewitness

Henry Wales was a British reporter who covered the execution. His story begins as Mata Hari is awakened in the early morning of 15 October. She had made a direct appeal to the French president for clemency and was expectantly awaiting his reply:[9]

The first intimation she received that her plea had been denied was when she was led at daybreak from her cell in the Saint-Lazare prison to a waiting automobile and then rushed to the barracks where the firing squad awaited her. Never once had the iron will of the beautiful woman failed her. Father Arbaux, accompanied by two sisters of charity, Captain Bouchardon, and Maitre Clunet, her lawyer, entered her cell, where she was still sleeping - a calm, untroubled sleep, it was remarked by the turnkeys and trusties. The sisters gently shook her. She arose and was told that her hour had come. 'May I write two letters?' was all she asked. Consent was given immediately by Captain Bouchardon, and pen, ink, paper, and envelopes were given to her. She seated herself at the edge of the bed and wrote the letters with feverish haste. She handed them over to the custody of her lawyer. Then she drew on her stockings, black, silken, filmy things, grotesque in the circumstances. She placed her high-heeled slippers on her feet and tied the silken ribbons over her insteps. She arose and took the long black velvet cloak, edged around the bottom with fur and with a huge square fur collar hanging down the back, from a hook over the head of her bed. She placed this cloak over the heavy silk kimono which she had been wearing over her nightdress. Her wealth of black hair was still coiled about her head in braids. She put on a large, flapping black felt hat with a black silk ribbon and bow. Slowly and indifferently, it seemed, she pulled on a pair of black kid gloves. Then she said calmly: 'I am ready.' The party slowly filed out of her cell to the waiting automobile. The car sped through the heart of the sleeping city. It was scarcely half-past five in the morning and the sun was not yet fully up. Clear across Paris the car whirled to the Caserne de Vincennes, the barracks of the old fort which the Germans stormed in 1870. The troops were already drawn up for the execution. The twelve Zouaves, forming the firing squad, stood in line, their rifles at ease. A subofficer stood behind them, sword drawn. The automobile stopped, and the party descended, Mata Hari last. The party walked straight to the spot, where a little hummock of earth reared itself seven or eight feet high and afforded a background for such bullets as might miss the human target. As Father Arbaux spoke with the condemned woman, a French officer approached, carrying a white cloth. 'The blindfold,' he whispered to the nuns who stood there and handed it to them. 'Must I wear that?' asked Mata Hari, turning to her lawyer, as her eyes glimpsed the blindfold. Maitre Clunet turned interrogatively to the French officer. 'If Madame prefers not, it makes no difference,' replied the officer, hurriedly turning away. Mata Hari was not bound and she was not blindfolded. She stood gazing steadfastly at her executioners, when the priest, the nuns, and her lawyer stepped away from her. The officer in command of the firing squad, who had been watching his men like a hawk that none might examine his rifle and try to find out whether he was destined to fire the blank cartridge which was in the breech of one rifle, seemed relieved that the business would soon be over. A sharp, crackling command and the file of twelve men assumed rigid positions at attention. Another command, and their rifles were at their shoulders; each man gazed down his barrel at the breast of the woman which was the target. She did not move a muscle. The underofficer in charge had moved to a position where from the corners of their eyes they could see him. His sword was extended in the air. It dropped. The sun - by this time up - flashed on the burnished blade as it described an arc in falling. Simultaneously the sound of the volley rang out. Flame and a tiny puff of greyish smoke issued from the muzzle of each rifle. Automatically the men dropped their arms. At the report Mata Hari fell. She did not die as actors and moving picture stars would have us believe that people die when they are shot. She did not throw up her hands nor did she plunge straight forward or straight back. Instead she seemed to collapse. Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her. She lay prone, motionless, with her face turned towards the sky. A non-commissioned officer, who accompanied a lieutenant, drew his revolver from the big, black holster strapped about his waist. Bending over, he placed the muzzle of the revolver almost - but not quite - against the left temple of the spy. He pulled the trigger, and the bullet tore into the brain of the woman. Mata Hari was surely dead.

—Henry Wales, International News Service, 19 October 1917

[edit] Disappearance and rumours

Mata Hari's body was not claimed by any family members and was accordingly used for medical study. Her head was embalmed and kept in the Museum of Anatomy in Paris, but in 2000, archivists discovered that the head had disappeared, possibly as early as 1954, when the museum had been relocated. Records dated from 1918 show that the museum also received the rest of the body but none of the remains could later be accounted for.

The fact that a former exotic dancer had been executed as a spy immediately provoked many unsubstantiated rumours. One is that she blew a kiss to her executioners, although it is possible that she blew a kiss to her lawyer, who was a witness to the execution and a former lover of hers. Her dying words were purported to be "Merci, monsieur". Another rumour claims that, in an attempt to distract her executioners, she flung open her coat and exposed her naked body. "Harlot, yes, but traitor, never," she is reported to have said. A 1934 New Yorker article, however, reported that at her execution she actually wore "a neat Amazonian tailored suit, specially made for the occasion, and a pair of new white gloves"[10] though another account indicates she wore the same suit, low-cut blouse and tricorn hat ensemble which had been picked out by her accusers for her to wear at trial, and which was still the only full, clean outfit which she had along in prison.[11] Neither description matches photographic evidence.

[edit] Museum

The Frisian Museum at Leeuwarden, the Netherlands, exhibits a 'Mata Hari Room'. Located in Mata Hari's native town, the museum is well-known for research into the life and career of Leeuwarden's world-famous citizen.

The Frisian Museum eagerly awaits the year 2017, when the French army is expected to release court documents about Mata Hari's trial and execution.

[edit] Legend and popular culture

The fact that almost immediately after her death questions rose about the justification of her execution, on top of rumours about the way she acted during her execution, set the story. The idea of an exotic dancer working as a lethal double agent, using her powers of seduction to extract military secrets from her many lovers fired the popular imagination, set the legend and made Mata Hari an enduring archetype of the femme fatale.

Much of the popularity is owed to the film titled Mata Hari (1931) and starring Greta Garbo in the leading role. While based on real events in the life of Margaretha Zelle, the plot was largely fictional, appealing to the public appetite for fantasy at the expense of historical fact. Immensely successful as a form of entertainment, the exciting and romantic character in this film inspired subsequent generations of storytellers. Eventually, Mata Hari featured in more films, television series, and in video games -- but increasingly, it is only the use of Margaretha Zelle's famous stage name that bears any resemblance to the real character. Many books have been written about Mata Hari, some of them serious historical and biographical accounts, but many of them highly speculative.

[edit] Movies and television

| Actress | Character | Appearance | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asta Nielsen | Mata Hari | Die Spionin | 1921 |

| Magda Sonja | Mata Hari | Mata Hari, die Rote Tänzerin | 1927 |

| Greta Garbo | Mata Hari | Mata Hari | 1931 |

| Jeanne Moreau | Mata Hari | Mata Hari, Agent H21 | 1964 |

| Joanna Pettet | "Mata Bond" the illegitimate child of Mata Hari and James Bond. |

Casino Royale | 1967 |

| Zsa Zsa Gabor | Mata Hari | Up the Front | 1972 |

| Sylvia Kristel | Mata Hari | Mata Hari | 1985 |

| Domiziana Giordano | Mata Hari | "Paris, October 1916" (an episode of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles) |

1993 |

| Michiko Neya Amanda Winn Lee (in English dubbing) |

Nancy Makuhari a clone of Mata Hari |

Read or Die | 2001 |

| Alyssa Milano | Mata Hari | "Used Karma" (an episode of Charmed where Milano's character Phoebe Halliwell was possessed by the restless spirit of Mata Hari) |

2004 |

[edit] Books and plays

- Lene Lovich co-wrote and performed Mata Hari, a play/musical at the Lyric Hammersmith, London, UK, Oct-Nov 1982.

- Author Kurt Vonnegut's character Howard W. Campbell, Jr. dedicates his "memoirs" to Mata Hari in the novel, Mother Night.

- Canadian poet John Oughton published an account of Mata Hari's life from her point of view titled Mata Hari's Lost Words (Ragweed Press, 1988).

- Diane Samuels' play, The True Life Fiction of Mata Hari (2001), deals with Mata Hari's interrogation and execution by the French military.

- Author Sam Waagenaar published the book The Murder of Mata Hari (1964, British edition. American edition, 1965 under the title Mata Hari), based on actual documentation, research, interviews with people who had known her as well as personal scrapbooks that Mata Hari had kept.

- Mata Hari appears as a student-Goddess in the novel The Breath of Gods by French writer Bernard Werber.

- In Kim Newman'salternate history novel The Bloody Red Baron, where Count Dracula survives to command the Central Powers during World War I, Mata Hari is one of the modern Brides of Dracula.

- The Brazilian novel Twelve Fingers (O Homem que Matou Getúlio Vargas) by Jô Soares has the protagonist meeting and romancing Mata Hari aboard the Orient Express.

[edit] Music

- Mr. Smolin's song, Mata Hari on his second album, "The Crumbling Empire of White People."[12]

- Nigel Clarke composed Three Symphonic Scenes for Concert Band entitled Mata Hari. Scene 1 is entitled 'Dancer in the Shadows', Scene 2 'Deceit and Seduction' and Scene 3 'Evasion and Capture'. The multi-award winning Northamptonshire Youth Concert Band, conducted by Peter Smalley, performed the British Premier of this piece in 2003.

- One of Ofra Haza's songs is entitled Mata Hari and based on her. One of the song's lyrics is: "Like a butterfly, she crossed all the lines...Like a butterfly she dreamt, danced and died".

- The 1999 Ricky Martin song "Shake Your Bon-Bon", she is mentioned in the line "You're a Mata Hari. I wanna know your story".

- Another mention in music comes in the Mary Prankster song "Mata Hari", discussing the reaction of society to openly sexual women.

- The Canadian ska band, The Kingpins, paid tribute to the spy in a song titled "Mata Hari" on their first full length album Watch Your Back.

- The musical Little Mary Sunshine has a number entitled "Mata Hari".

- A musical entitled "Mata Hari" was originally intended to run on Broadway, but it flopped and disappeared after its out-of-town try-out. The musical was revived in 1995 by the York Theatre Company and was recorded.

- Norway, represented in 1976 by Anna-Karina Ström, performed the song "Mata Hari" came in 17th during the Eurovision Song Contest in The Hague. It contains the lyrics "You walked away laughing and left them alone with their shame".

- One of The Atomic Fireballs songs is entitled Mata Hari.

- In the Bone Machine press kit, Rip Tense in 1992, Tom Waits mentions that he cut out a verse about Mata Hari from the song "Dirt In The Ground" because the song was running long. He stated that "One of (the verses) was: Mata Hari was a traitor, they sentenced her to death/The priest was at her side and asked her if she would confess/She said, 'Step aside, Father, it's the firing squad again/And you're blocking my view of these fine lookin' men.'/And we're all gonna be dirt in the ground... That's what people say that were present, that just before the firing squad opened up she opened up her blouse a little bit, and then she winked, and then they took her down."[13]

[edit] Painting

In 1916 the renowned Dutch artist Isaac Israëls painted Mata Hari. His work of art is exhibited in the famous Kröller-Müller Museum at Otterlo, the Netherlands.

[edit] Games

- There was a video game Mata Hari by Loriciels, for Amstrad CPC (1988) and Atari ST (1989).

- Mata Hari appears as a spy in the first two games of the Shadow Hearts video game series, under her true name, though Anglicised to Margarete Gertrude Zelle.

- Mata Hari appears as a Great Spy unit in the Civilization IV expansion Beyond the Sword.

- In the video game Metal Gear Solid 3 the character EVA is nicknamed Mata Hari when the protagonist questions her about betraying her country.

- An enigmatic exotic dancer goes by the stage name of Mata Hari in the PC adventure game, Culpa Innata (2007).

- There was a 1977 Bally Pinball Machine based on Mata Hari.

[edit] Bibliography

- Marijke Huisman, Mata Hari (1876-1917): de levende legende, a good Dutch historical review. Editing House Verloren at Hilversum, the Netherlands, ISBN 90-6550-442-7.

- Shipman, Pat Femme Fatale: A Biography of Mata Hari Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2007, ISBN 0-297850-74-1 ISBN-13 978-0297850748 (USA edition: Femme Fatale: Love, Lies, and the Unknown Life of Mata Hari William Morrow, 2007, ISBN 0-060817-28-3 ISBN-13 9780060817282)

[edit] References

- ^ "Mata Hari". Encyclopædia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/women/article-9051346. Retrieved on 2007-08-21. "The daughter of a prosperous hatter, she attended a teachers' college in Leiden. In 1895 she married an officer of Scottish origin, Captain Campbell MacLeod, in the Dutch colonial army, and from 1897 to 1902 they lived in Java and Sumatra. The couple returned to Europe but later separated, and she began to dance professionally in Paris in 1905 under the name of Lady MacLeod. She soon called herself Mata Hari, said to be a Malay expression for the sun (literally, “eye of the day”). Tall, extremely attractive, superficially acquainted with East Indian dances, and willing to appear virtually nude in public, she was an instant success in Paris and other large cities. Throughout her life s"

- ^ www.praamsma.org - Mata Hari

- ^ a b c Article of the About.com Internet site. [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Out of World of Biography Internet site. [2]

- ^ a b Mata Hari

- ^ The Spy Who Never Was, by Julia Keay, published by Michael Joseph Ltd, 1987

- ^ Shipman, Pat (2007). Femme Fatale: Love, Lies, and the Unknown Life of Mata Hari. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 450. ISBN 0-06-081728-3.

- ^ www.crimelibrary.com - Mata Hari is Born

- ^ account originally published in newspapers through the International News Service on Oct. 19, 1917, republished in Carey, John, EyeWitness to History (1987); Howe, Russell Warren, Mata Hari: The True Story (1986)

- ^ Flanner, Janet (1979). Paris was Yesterday: 1925-1939. New York: Penguin. pp. 126. ISBN 0-14-005068-X.

- ^ Shipman, Pat (2007). Femme Fatale: Love, Lies, and the Unknown Life of Mata Hari. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 450. ISBN 0-06-081728-3.

- ^ Mr. Smolin--The Crumbling Empire Of White People

- ^ Tom Waits Library

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Mata Hari |

- Biography at Court TV's Crime Library

- Details of the disappearance of the corpse

- "The Execution of Mata Hari, 1917," EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2005)

- Mata-Hari.com: Pictures and Photos of Mata Hari (english + deutsch + español + português + français + italiano)