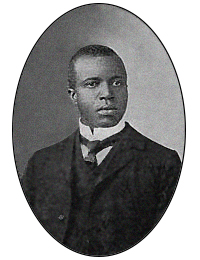

Scott Joplin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Scott Joplin | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Scott Joplin |

| Born | November 24, 1868 |

| Origin | Linden, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | April 1, 1917 (aged 48) |

| Genre(s) | Ragtime, March, Waltz, and Song |

| Occupation(s) | Composer musician, and pianist |

| Instrument(s) | Piano |

| Years active | 1898 - 1916 |

Scott Joplin (November 24, 1868 – April 1, 1917) was an African American composer and pianist, born near Texarkana, Texas, into the first post-slavery generation - his father an ex-slave and his mother a freeborn woman. He would achieve fame for his unique ragtime compositions, and would later be dubbed the "King of Ragtime." During his brief career, he wrote forty-four original ragtime pieces, one ragtime ballet, and two operas, with one of his first pieces, the Maple Leaf Rag, becoming ragtime's first and most influential hit, and remaining so for a century.

He was blessed with an amazing ability to improvise at the piano, and was able to enlarge his talents with the music he heard around him, which was rich with the sounds of gospel hymns and spirituals, dance music, plantation songs, syncopated rhythms, blues, and choruses. After studying music with several local teachers, his talent was noticed by a German immigrant music teacher, Julius Weiss, who chose to give the 11 year old boy lessons free of charge. He was taught music theory, keyboard technique, and an appreciation of various European music styles, such as folk and opera. As an adult he also studied at an all-black college in Sedalia, Missouri.

"He composed music unlike any ever before written," according to Joplin biographer Edward Berlin. Eventually, "the piano-playing public clamored for his music; newspapers and magazines proclaimed his genius; musicians examined his scores with open admiration." Ragtime historian Susan Curtis noted that "when Joplin syncopated his way into the hearts of millions of Americans at the turn of the century, he helped revolutionize American music and culture."

He spent his final years, before his early death at age 48, working on his second opera, Treemonisha. This was written, according to opera historian Elise Kirk, to be a "timeless story" about a young black "heroine of the spirit who leads her people from superstition and darkness to salvation and enlightenment." It was a failure in its first concert performance in 1915, but was rediscovered and premiered in 1972[1]. Joplin's music returned to popularity in the 1970s with the Academy award-winning movie The Sting, which featured several of his compositions, such as The Entertainer[2]. Joplin was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1976[3].

Contents |

[edit] Early years

[edit] Family life

Scott Joplin, the second of six children, was born in eastern Texas, outside of Texarkana,[4] to Jiles Joplin and Florence Givins. His father was an ex-slave from North Carolina while his mother was a freeborn woman from Kentucky.[5] After moving to Texarkana a few years after Scott was born, Jiles began working as a common laborer for the railroad while his mother did laundry and cleaning for additional income. Berlin writes that they "were a musical family and provided their son a rudimentary musical education." At the age of seven, for instance, Scott was allowed to play piano in both a neighbor's house and at the home of an attorney while his mother worked at housecleaning.[6]

[edit] Learning music and piano

Berlin notes that Jiles "left the family in the early 1880s, going to live with another woman..."[6] As a result, Florence "assumed support of the family with domestic work," and often while she worked, Scott would use her employer's piano when there was one in the house. According to a family friend, "the young Scott was serious, ambitious, and spoke of his intention to make something of himself." He taught himself to play by sight and improvisation, and received some basic guidance from family friends.

However, Berlin adds, "a more significant influence was a German immigrant music teacher who has been identified as Julius Weiss." Weiss, according to Berlin, somewhere heard him play and was so "impressed with the talent of the young Scott," he gave him lessons free of cost in order to expose him to various forms of European music, such as folk and opera. Berlin writes, "The essence of what Weiss accomplished was to impart to Scott an appreciation of music as an art as well as entertainment. . . Weiss helped shape Joplin's aspirations and ambitions toward high artistic goals. . . and the evidence suggests that he had a profound influence on the young Joplin." [6] There is also evidence that he later helped Joplin's mother acquire their first used piano from another one of his clients who had bought a new one.[7]

Joplin's widow later confirmed these details to music historian Theodore Albrecht, adding that the "professor also played the classics for him and talked about the great composers." Albrecht learned that Weiss, then age thirty-nine, was born in Saxony, had studied music at the University of Saxony, and was listed as "Professor of Music" in the town's records. He adds, "there is evidence that he might have been Jewish," as he shared a room with another immigrant who was "a prominent member of the early Jewish community in Texarkana." After Joplin achieved fame as a composer, Albrecht notes that "he never forgot Weiss, his first benefactor," who remained single and fell on hard times. According to Joplin's widow, "he sent his teacher, by then ill and poor, gifts of money from time to time."[7]

Scott's early exposure and appreciation to music was further enhanced by the "air" in Texarkana, which Joplin biographer Susan Curtis described as "rich with sounds - work songs, gospel hymns and spirituals, dance music, and the classical compositions to which his German music teacher introduced him." Curtis adds that because of his "natural ability," this atmosphere contributed to his "inventing the kind of ragtime that became celebrated in the 1890s as a blend of African American and European forms and melodies."[8]

[edit] Family problems

While Berlin wrote that Scott's father left the family in the early 1880s, Susan Curtis has uncovered that some of the causes for the family's tensions and separation were due to Scott's talent. She describes this period of Scott's life:

- "Scott's piano playing and education with his German music teacher apparently became a source of controversy within the Joplin family. On the one hand, the boy's talent attracted considerable attention ... which must have been a source of pride for his parents... On the other hand, Jile's opposition probably stemmed from the fact that Scott's concentration on music took him away from some kind of practical employment which would have supplemented the family income.... Florence's encouragement of her son's musical ambitions angered her husband, and, as Joplin entered his teens, became the source of serious division within the family."[8]

[edit] Early recognition

According to Curtis, in spite of the tensions at home, Joplin immersed himself in the musical life of the community. He played music at church gatherings and for "secular entertainments." She adds that it is likely he played "waltzes, polkas, and schottisches for African American dances," although he was known primarily for the originality of his music. One lady who heard him play insisted that "Scott worked on his music all the time. He was a musical genius. He didn't need a piece of music to go by. He played his own music without anything." Another remembered, "He did not have to play anybody else's music. He made up his own, and it was beautiful; he just got his music out of the air."[8]

[edit] Music career

[edit] Early career

As a teenager, Joplin began performing at various local events. Then sometime in the late 1880s, he chose to give up his only steady employment as a laborer with the railroad and left Texarkana to "support himself as an itinerant musician," writes historian Lawrence Christensen.[9] He was soon to discover that there were few opportunities for black pianists, however. Besides the church, brothels were one of the few options for obtaining steady work. Kirk writes that "he played pre-ragtime ('jig-piano') in various red-light districts throughout the mid-South."[10] He also managed to fit in classes in composition and counterpoint at one of the nation's first all-black academic institutions, the George R. Smith College for Negroes in Sedalia, Missouri.

In 1893 he made his way to Chicago to perform for the visitors to the World's Fair, although not as an official performer. Instead, like other black entertainers, he found work in the cafés that lined the fair, "as well as the city's tenderloin district." While in Chicago he formed his first band and began arranging music for the group to perform. Although the World's Fair was "not congenial to African Americans," he still found that "visitors clamored to hear their music," along with the music of the other black performers.[9] According to historian William Scott, Dispatch News described ragtime as "a veritable call of the wild, which mightily stirred the pulses of city bred people." Whatever its origins, by 1897, notes Scott, "ragtime had become a national craze, setting the tempo for American cities prior to World War I."[11]

[edit] Ragtime composer and pianist

[edit] Music style origins

According to jazz historian John Tennison, Joplin's teacher, Julius Weiss, was classically trained in Germany and "might very well have brought a Polka "oompah" rhythmic sensibility from the old country to Texarkana, where he gave 11-year old Joplin free lessons.[12] This idea is supported by others: According to jazz historian Francis Davis, "Ragtime borrowed its harmonic schemes and its march-like tempos from Europe, but the syncopations that marked it as new were African-American in origin..."[13]

Jazz historian Martin Williams, in The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, states, "Ragtime was basically a piano keyboard music and one might say, an Afro-American version of the polka, or its analog, the Sousa-style march."[14] Whereas jazz historian David Jasen called this synthesis "a new art form, the Classic rag. . . [which] combined the traditions of Afro-American folk music with nineteenth-century European romanticism...."[15] With this as a foundation, Joplin intended his compositions to be played exactly as he wrote them - without improvisation. As Scott adds, "Like the European tradition, Joplin limited musical creativity to the composer."[11]

This was a new direction for ragtime. Susan Curtis points out that when Joplin was learning piano, "ragtime music was roundly condemned in serious musical cirles," due to its reputation of being a "low form of music because of songs with vulgar lyrics and inane melodies cranked out by the tune-smiths of Tin Pan Alley." She infers that Joplin's contact with a man like Weiss "would have have important consequences for an African American in northeastern Texas. The educated German could open up the door to a world of learning and music of which young Joplin was largely unaware."[8] Eventually, on his own, he would succeed in elevating ragtime above the low and unrefined impressions engrained in the public's mind. As Whitcomb describes his transition, he would from then on refuse to be just another "one of those wandering honky tonk pianists. . . content to celebrate just the passing moment . . . killing himself with booze and the sporting life by playing mere dance music ..."[16] Instead, he would soon help ragtime attain national prominence with a more "delicate form leaning toward the concert hall."

[edit] First hit: "Maple Leaf Rag"

He moved to Sedalia, Missouri in 1894, and began working as a pianist in the Maple Leaf Club and the Black 400, social clubs for "respectable [black] gentlemen". According to Scott, he had established himself "as Sedalia's best piano player," although a number of his friends said that he played slowly, but exceedingly good. "He also began composing songs and taught music,"[11]

In 1899, Joplin sold what would soon become one of his most famous pieces, "Maple Leaf Rag", to John Stark & Son, a Sedalia music publisher. It was an immediate success and was ragtime's first hit, remaining so for a century. It also served as a model for the hundreds of rags to come from future composers. Jazz historian Bill Kirchner notes that "Joplin influenced his peers, not only in the form of the rag but in techniques of composition, especially in subtle uses of syncopation." He adds however, that although other composers had studied and learned from "Maple Leaf," and acknowledged its lead, except for Joseph Lamb, they "failed to enlarge upon it." [5] Nonetheless, with the "ebullient, ever-popular" "Maple Leaf Rag", Joplin soon became known as King of Ragtime, according to opera historian Elise Kirk, and Tennison calling him the Father of Ragtime.[12]

Becoming the first instrumental to sell over one million copies, "Maple Leaf Rag" put Joplin on the top of the list of ragtime performers and moved ragtime into a popular musical form. He lived in St. Louis from 1900 to 1903, where he then produced some of his best-known works, such as "The Entertainer," "Elite Syncopations," "March Majestic," and "Ragtime Dance." Throughout his life he composed at least forty similar rags, what Kirk describes as "creative miniatures," that he considered "classical" music. She adds, "And he succeeded. Joplin's piano rags are more tuneful, contrapuntal, infectious, and harmonically colorful than any others of his era."[10]

But Kirchner finds it "fatefully odd that Joplin's work, the guiding influence in ragtime's earlierst days, did not enjoy continuing exposure." Even after the success of "Maple Leaf," he composed a body of rags, that Kirchner writes are "of increasing lyrical beauty and delicate syncopation." [5] But except for "Maple Leaf" and a couple of others, these rags "remained unheralded and obscure" during his lifetime. Joplin apparently realized that his music was ahead of its time: As music historian Ian Whitcomb mentions, Joplin "opined that 'Maple Leaf Rag' would make him 'King of Ragtime Composers' but he also knew that he would not be a pop hero in his own lifetime. 'When I'm dead twenty-five years, people are going to recognize me,' he told a friend." Just over thirty years later he was recognized, and later historian Rudi Blesh would write a large book about ragtime, which he dedicated to the memory of Scott Joplin.[16]

[edit] Opera composer: "Treemonisha"

[edit] Origins

In 1907, Joplin moved to New York believing that it was the best possible place to find a producer for his new opera. He had already written two previous theatrical works, the six-minute Ragtime Dance (1899) and the opera A Guest of Honor (1903), the score of which is lost. But in his "quest for artistic merit," notes opera historian Elise Kirk, he gave his opera Treemonisha "a life of its own" which became his "obsession," a composition which he "seemed to cherish beyond all his other works."[10] Kirk describes the qualities of the opera:

- "It was dignified, and beautiful; it embodied a classical elegance, myth, message, and buoyancy; and it both reflected and reinforced his inner life and spirit. He could identify with its characters. To him, they were real, and his music richly promulgated that reality."[10]

[edit] Story and coincidences

According to music historian Richard Crawford, based on the opera's libretto (written text,) the story takes place in a rural setting near Texarkana, where Joplin grew up. "The story seems laced with elements of autobiography," Crawford observes. It centers on Treemonisha, "a girl of eighteen who hopes to lead her community out of ignorance, superstition, and misery by teaching them the value of education."[17] And historian Willam Scott describes it as "a mythical story of black emergence into the modern world. . . a story about his own people that drew on African American music and dance." [11]

But Berlin speculates on additional meanings and notes that "by setting the opera near his childhood home of Texarkana, Joplin alerts us to watch for autobiograhical references." He writes:

- "... the story is an allegory with wider ramifications. The subject is really the African American community which, as seen by Joplin fewer than fifty years after emancipation, was still living in ignorance, superstition, and misery. The way out of this condition, he tells his intended audience, is with the education that can be provided by white society. . . .

- "Education is central to the story, as it was to Joplin's life. 'Ignorance is criminal,' he tells his audience. Education was widely regarded as the means by which black Americans would earn the respect and acceptance of the rest of American society. . . Treemonisha was educated by a white woman, just as Joplin received his education from a white music teacher. . . "

Berlin also notes that in the opera's preface, Joplin states that Treemonisha began her education "at the age of seven," which is the same age that Joplin started his. And Berlin adds that the timeline of the opera is "particularly perplexing:" The opera begins in 1884, as an eighteen-year old Treemonisha "starts upon her career as a teacher and a leader." This was also the year that Joplin's music teacher, Julius Weiss, moved from Texarkana. Berlin speculates on the coincidence and questions whether Treemonisha represents Joplin:

- "With his teacher no longer available to him, the 16-year-old Scott saw no reason to remain in town. In 1884, he then set off upon his career as a musician, perhaps with hopes of eventually becoming a teacher and leader of his people, the course he ascribes to his heroine Treemonisha."[6]

[edit] Writing the score

Nonetheless, Kirk writes that soon "reality became bitter for Joplin." She feels that the public was not yet ready for "crude" black musical forms, which were so different from the style of European grand opera of that time, regardless of its "excellent craftsmanship." Furthermore, she points out, "The story itself is timeless. All can relate to its message, making it one of America's earliest family operas, . . . and an excellent vehicle for introducing children to both opera and their national heritage." [10] Yet he was unable to find a publisher.

Possibly realizing he was suffering from incurable syphilis, Joplin biographer Vera Brodsky Lawrence described this period in Joplin's life:

- "It was the rejection after rejection that came to erode the very foundations of his existence. He gave up his public playing, dismissed or lost his students, and eventually even sacrificed his composing to his monomania. He plunged feverishly into the task of orchestrating his opera, day and night, with his friend Sam Patterson standing by to copy out the parts, page by page, as each page of the full score was completed. Perhaps Joplin was aware of his advancing deterioration and was consciously racing against time."[18]

[edit] Performance and reception

In 1911, unable to find a publisher, he undertook the financial burden of publishing "Treemonisha" himself in piano-vocal format and as a last resort to see it staged invited a small audience to hear it at a rehearsal hall in Harlem, in 1915. Poorly staged and with only himself on piano accompaniment, it was "a miserable failure," notes Kirk. While Scott concludes that "after a disastrous single performance . . . Joplin suffered a breakdown. He was bankrupt, discouraged, and worn out." And according to Scott, few American artists of his generation faced such obstacles. "Treemonisha went unnoticed and unreviewed, largely because Joplin had abandoned commercial music in favor of art music, a field closed to African Americans."[11] In fact, it was not until the 1970s that the opera received a full theatrical staging.

Ragtime historian Terry Waldo notes that the opera was ahead of its time: "like ragtime music itself, "Treemonisha" was an entirely new art form that was probably only approached in style in the 1920s..." He notes that the opera is a combination of folk music in the framework of a European opera, but is also Joplin's re-creation of his own experiences as an African American man using an opera as a means of expression. But Waldo adds, "such an undertaking was doomed to failure - but failure on such a grand scale that it cannot be dismissed lightly. It is a magnificent attempt, and parts of it approach greatness."[19]

[edit] Social significance

Kirk concludes that if "Treemonisha" was not sophisticated enough for Harlem in 1915, "it has felicitously found a place in ... American operas." She notes that it occupies a special place in American history as well. "The opera's young heroine is a startlingly early voice for modern civil rights causes, notably the importance of education and knowledge to African American advancement."[10] Christensen's conclusion is similar: "In the end, "Treemonisha" offered a celebration of literacy, learning, hard work, and community solidarity as the best formula for advancing the race."[9]

Because of the opera's early failure after years of obsessive labor, a year later, in 1916, his wife Lottie had to have him committed to the Manhattan State Hospital, where he died a year later of dementia,[11] and what Kirk speculates was "a state of mental deterioration from conditions related to syphilis."[10]

[edit] Personal life and marriages

Joplin moved to St. Louis in early 1900 with his new wife, Belle. Belle was a sister-in-law of Scott Hayden, who collaborated with Joplin in the composition of four rags.[15] They later divorced.

In June 1904, Joplin married Freddie Alexander of Little Rock, Arkansas, the young woman to whom he had dedicated "The Chrysanthemum" (1904). She died on September 10, 1904 of complications resulting from a cold, ten weeks after their wedding.[20] Joplin's first work copyrighted after Freddie's death, "Bethena" (1905), was described by one biographer as "an enchantingly beautiful piece that is among the greatest of Ragtime Waltzes".[6]

In 1907 Scott Joplin moved to New York City, where he met Lottie Stokes, whom he married in 1909. In 1913, they formed the Scott Joplin Music Company, and together published his "Magnetic Rag."

[edit] Final years and early death

Joplin was hopeful that his final opera, "Treemonisha," which filled 230 page of sheet music and took years of single-minded devotion to finish, would be successful. In the end, however, he could not interest producers to finance the huge project. Then, in 1915, at his own expense, he gave a single performance which received only unfavorable reviews. He closed the show after that initial performance, but never recovered from that great disappointment.

His depression continued to worsen and accelerated what others believe were the effects of terminal syphilis. He died in Manhattan State Hospital on April 1, 1917, at the age of forty-eight.

[edit] Legacy

According to music historians William Scott and Peter Rutkoff, Joplin and his fellow ragtime composers rejuvenated American popular music. Ragtime fostered an appreciation for African American music among European Americans by creating exhilarating and liberating dance tunes, changing American musical taste. "Its syncopation and rhythmic drive gave it a vitality and freshness attractive to young urban audiences indifferent to Victorian proprieties. . . Joplin's ragtime expressed the intensity and energy of a modern urban America."[11]

Joshua Rifkin, a leading Joplin recording artist, wrote that "a pervasive sense of lyricism infuses his work, and even at his most high-spirited, he cannot repress a hint of melancholy or adversity. . . He had little in common with the fast and flashy school of ragtime that grew up after him."[21]

Joplin biographer Susan Curtis expands on those observations:

- "When Scott Joplin syncopated his way into the hearts of millions of Americans at the turn of the century, he helped revolutionize American music and culture. His ragged rhythms and lilting melodies made people want to tap their feet, slap their thighs, or dance with happy abandon. As Americans embraced his music, they participated in a dramatic transformation of American popular culture -- their Victorian restraint gave way to modern exuberance. And whether in the elegant parlors of comfortable, respectable American homes or in the honky tonks and cafes of America's sporting districts, ragtime music accompanied a reorientation of cultural values in America in the twentieth century. The excellence and appeal of his compositions earned for Joplin the generally accepted title King of Ragtime."[8]

Although he was penniless and disappointed at the end of his life, Joplin set the standard for ragtime compositions and played a key role in the development of ragtime music. And as a pioneer composer and performer, he helped pave the way for young black artists to reach American audiences of both races. And when he died, notes jazz historian Floyd Levin, "those few who realized his greatness bowed their heads in sorrow. This was the passing of the king of all ragtime writers, the man who gave America a genuine native music."[22]

[edit] Revival

After his death in 1917, Joplin's music and ragtime in general waned in popularity as new forms of musical styles, such as jazz and novelty piano, emerged. Even so, Jazz bands and recording artists such as Tommy Dorsey in 1936, Jelly Roll Morton in 1939 and J. Russell Robinson in 1947 released recordings of Joplin ragtime compositions ragtime on 78 RPM records. Between 1902 and 1961 more recordings of the Maple Leaf Rag were released by more artists than for any other Joplin rag. [23]

[edit] 1960s

In the 1960s, a small-scale reawakening of interest in classic ragtime was underway among some American music scholars. In 1961, composer and performer Trebor Tichenor began publishing The Ragtime Review and hosting ragtime performances aboard a St. Louis riverboat named Goldenrod. In New York City, William "Bill" Bolcom learned of the existence of the opera Treemonisha in 1966 and began to search for it, finding that Rudi Blesh had published it a few years prior. Bolcom arranged with Thomas J. "T.J." Anderson for a full orchestration of the work and, in the meantime, began playing and composing rags, sending sheet music back and forth with his friends William "Bill" Albright and Peter Winkler, a mathematician and fan of ragtime. Blesh's friend Max Morath introduced them to the breadth of Joplin's rags. In 1968, Bolcom and Albright interested Joshua Rifkin, a young musicologist, in the body of Joplin's work. Together, they hosted an occasional ragtime-and-early-jazz evening on WBAI radio.[19]

[edit] Joshua Rifkin

In November 1970, Rifkin released a recording called Scott Joplin Piano Rags[24] on the classical label Nonesuch."Listen" It sold 100,000 copies in its first year and eventually became Nonesuch's first million-selling record.[25] Record stores found themselves for the first time putting ragtime in the classical music section. The album was nominated in 1971 for two Grammy Award categories: Best Album Notes and Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra). Rifkin was also under consideration for a third Grammy for a recording not related to Joplin, but at the ceremony on March 14, 1972, Rifkin did not win in any category.[26]

[edit] New York publishing

In January 1971, Harold C. Schonberg, music critic at the New York Times, having just heard the Rifkin album, wrote a featured Sunday edition article entitled "Scholars, Get Busy on Scott Joplin!"[27] Schonberg's call to action has been described as the catalyst for classical music scholars, the sort of people Joplin had battled all his life, to conclude that Joplin was a genius.[19] Vera Brodsky Lawrence of the New York Public Library published a two-volume set of Joplin works in June 1971, entitled The Collected Works of Scott Joplin, stimulating a wider interest in the performance of Joplin's music.

[edit] Treemonisha productions

On October 22, 1971 excerpts from Treemonisha were presented in concert form at Lincoln Center with musical performances by Bolcom, Rifkin and Mary Lou Williams supporting a group of singers.[28] Finally, on January 28, 1972, T.J. Anderson's orchestration of Treemonisha was staged for two consecutive nights, sponsored by the Afro-American Music Workshop of Morehouse College in Atlanta, with singers accompanied by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra[29] under the direction of Robert Shaw, and choreography by Katherine Dunham. Schonberg remarked in February 1972 that the "Scott Joplin Renaissance" was in full swing and still growing.[30]

[edit] Gunther Schuller

Gunther Schuller, a french horn player and music professor, formed the New England Ragtime Ensemble in 1972 from students at the New England Conservatory. He had received mimeographed copies of individual instrumental parts of the Red Back Book from Vera Lawrence, and was introducing Joplin tunes into the middle of otherwise 'classical' concerts of American turn-of-the-century music. Angel Records approached him with a record deal and, in 1973, produced a recording called Joplin: The Red Back Book.

[edit] The Sting

After Marvin Hamlisch produced the soundtrack for The Sting in 1973, won an Oscar for his adaptation of Joplin's music, [31], and got his adaptation of The Entertainer on the Billboard Hot 100 music chart in 1974, "the whole nation has begun to take notice...", wrote the New York Times. [32]

New York Magazine, in 1979, wrote that Nonesuch Records, by giving artists like Rifkin their "first hearing" by recording Joplin's music, "created, almost alone, the Scott Joplin revival."[33] In his interview with the Times, Rifkin stated, "Let's face it - the big factor here is the score for The Sting." However, Rifkin pointed out that the movie's score was a "direct stylistic lift from two sources. ...What you get in the movie is piano solos played exactly like mine and the orchestral arrangements done exactly like his [Schuller]."[32] The Grammy-nominated recordings remained at the top of Billboard's classical charts for some time.[34]

Edward Berlin tends to agree that the movie was an important factor in the revival: "Led by The Entertainer, one of the most popular pieces of the mid-1970s, a revival of his music resulted in events unprecedented in American musical history." He further added, "never before had any composer's music been so acclaimed by both the popular and classical music worlds." [6] The New York Times described some of the revival's effects on the public:

- "Joplin's music, happily, is just about omnipresent these days. His The Entertainer ... reverberates from every jukebox and car radio; companies like Kodak and Ford are using rags ... as background music for television commercials; ragtime renditions by everybody from Percy Faith to E. Power Biggs ... crowd together on record store shelves."[32]

Rifkin had also been affected by the revival: In 1974 he said, "I did a tour this fall and various other concerts since then, including two in London - there's a craze in England as well - and made something like ten appearances on BBC television this spring ... This past May I gave a concert in London's Royal Festival Hall, which seats about 3,200 people, and it was sold out within four days..."[32]

[edit] Ballet

Also that year the Royal Ballet, under Kenneth MacMillan created Elite Syncopations, a ballet based on tunes by Joplin, Max Morath and others. In addition, 1974 also saw the premiere by the Los Angeles Ballet of Red Back Book, choreographed by John Clifford to Joplin rags from the collection of the same name, including both solo piano performances and arrangements for full orchestra.

[edit] Treemonisha on Broadway

In May 1975, Treemonisha was staged in a full opera production by the Houston Grand Opera. The company toured briefly, then settled into an eight-week run in New York on Broadway at the Palace Theater in October and November. This appearance was directed by Gunther Schuller, and soprano Carmen Balthrop alternated with Kathleen Battle as the title character.[29] An "original Broadway cast" recording was produced. Because of the lack of national exposure given to the brief Morehouse College staging of the opera in 1972, many Joplin scholars wrote that the Houston Grand Opera's 1975 show was the first full production.[28]

[edit] Other awards and recognition

In 1970, Joplin was inducted in the Songwriters Hall of Fame by the National Academy of Popular Music.[35]

In 1976 Joplin was awarded a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for his special contribution to American music.[3] A star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame was placed in his honor. Motown Productions produced a Scott Joplin biographical film starring Billy Dee Williams as Joplin, released by Universal Pictures in 1977. In 1983, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp of the composer as part of its Black Heritage commemorative series.

In 2002, a collection of Scott Joplin's own performances recorded on piano rolls in the 1900s was included by the National Recording Preservation Board in the Library of Congress National Recording Registry.[36] The board selects songs in an annual basis that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

|

|||||

| Problems listening to this file? See media help. | |||||

[edit] References

[edit] Notes

- ^ "Opera America". http://web.archive.org/web/20050218222938/http://www.operaam.org/encore/tree.htm. Retrieved on 2009-03-14.

- ^ "IMDB.com". http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070735/soundtrack. Retrieved on 2009-03-14.

- ^ a b "The Pulitzer Prize - Special Awards and Citations". http://www.pulitzer.org/bycat/Special+Awards+and+Citations. Retrieved on 2009-03-14.

- ^ "Texas Music History Online - Scott Joplin". http://ctmh.its.txstate.edu/artist.php?cmd=detail&aid=29. Retrieved on 2006-11-22.

- ^ a b c Kirchner, Bill. The Oxford Companion to Jazz, Oxford Univ. Press (2005)

- ^ a b c d e f Berlin, Edward A. Kind of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era, Oxford Univ. Press (1996)

- ^ a b Albrecht, Theodore. Julius Weiss: Scott Joplin's First Piano Teacher, Case Western Univ., College Music Symposium, 19, (Fall 1979): pgs 89-105

- ^ a b c d e Curtis, Susan. Dancing to a Black Man's Tune: A Life of Scott Joplin, Univ. of Missouri Press (2004)

- ^ a b c Christensen, Lawrence O. Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Univ. of Missouri Press (1999)

- ^ a b c d e f g Kirk, Elise Kuhl. American Opera, Univ. of Illinois Press (2001)

- ^ a b c d e f g Scott, William B., and Rutkoff, Peter M. New York Modern: The Arts and the City Johns Hopkins Univ. Press (2001)

- ^ a b Tennison, John. "History of Boogie Woogie", Chapter 15, "Contrasts Between Boogie Woogie and Ragtime"

- ^ Davis, Francis. The History of the Blues, Hyperion (1995)

- ^ Martin, Williams. The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz, Smithsonian Institution Press (1987)

- ^ a b Jasen, David A. and Tichenor, Trebor Jay. Rags and Ragtime: A Musical History, Dover Books (1978)

- ^ a b Whitcomb, Ian. After the Ball, Hal Leonard Corp. (1986)

- ^ Crawford, Richard. America's Musical Life: a History W. W. Norton & Co. (2001)

- ^ Lawrence, Vera Brodsky. Scott Joplin : Collected Piano Works, The New York Public Library (June, 1971)

- ^ a b c Waldo, Terry. This is Ragtime, Da Capo Press (1976)

- ^ "A Biography of Scott Joplin". http://www.scottjoplin.org/biography.htm. Retrieved on 2008-10-03.

- ^ Rifkin, Joshua. Scott Joplin Piano Rags, Nonesuch Records (1970) album cover

- ^ Levin, Floyd. Classic Jazz: A Personal View of the Music and the Musicians, Univ. of California Press (2002)

- ^ Jasen, David A, Discography of 78 rpm Records of Joplin Works, Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works, New York Public Library, (1981), pp.319-320

- ^ Nonesuch Records. Scott Joplin Piano Rags. Joshua Rifkin, piano. Retrieved on March 19, 2009.

- ^ Nonesuch Records. About. Retrieved on March 19, 2009.

- ^ Awards Database - LA Times|accessdate=2009-03-17}}

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (24 January 1971). "Scholars, Get Busy on Scott Joplin!". New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40D1FFD3B5F127A93C6AB178AD85F458785F9. Retrieved on 20 March 2009.

- ^ a b Ping-Robbins, Nancy R. (1998). Scott Joplin: a guide to research. p. 289. ISBN 0-8240-8399-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=0FeXfmHEXfIC&pg=PA289&lpg=PA289. Retrieved on 2009-03-20.

- ^ a b Peterson, Bernard L. (1993). A century of musicals in black and white. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 357. ISBN 0-313-26657-3. http://books.google.com/books?id=VQggZdq1hawC&pg=PA357&lpg=PA357. Retrieved on 2009-03-20.

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C. (13 February 1972). "The Scott Joplin Renaissance Grows". New York Times. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50F11F73C591A7493C1A81789D85F468785F9. Retrieved on 20 March 2009.

- ^ "Entertainment Awards Database - LA Times". http://theenvelope.latimes.com/factsheets/awardsdb/env-awards-db-search,0,7169155.htmlstory?target=article&searchtype=all&Query=. Retrieved on 2009-03-14.

- ^ a b c d Kronenberger, John. "The Ragtime Revival-A Belated Ode to Composer Scott Joplin", New York Times, August 11, 1974

- ^ New York Magazine, December 24, 1979 pg. 81

- ^ The Envelope Please - LA Times, Los Angeles Times, 1971

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame". http://songwritershalloffame.org/exhibits/C297. Retrieved on 2009-03-17.

- ^ 2002 National Recording Registry choices

[edit] Bibliography

- Blesh, Rudi. Scott Joplin: Black-American Classicist, Introduction to Scott Joplin Complete Piano Works, New York Public Library, (1981)

- Gioia, Ted (1997). The History of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509081-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=Ff94HgAACAAJ.

- Haskins, James (1978). Scott Joplin. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc. ISBN 0-385-11155-X. http://books.google.com/books?id=TfcyAAAACAAJ.

- MaGee, Jeffrey (1998). "Ragtime and Early Jazz". in David Nicholls (ed.). 'The Cambridge History of American Music'. New York: The Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521454298. http://books.google.com/books?id=-pbKjje254AC.

- Waterman, Guy (1985a). "Ragtime". in J.E. Hasse (ed.). 'Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music'. New York: Shirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-871650-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=y9PBAAAACAAJ.

- Waterman, Guy (1985b). "Joplin's Late Rags: An Analysis". in J.E. Hasse (ed.). 'Ragtime: Its History, Composers, and Music'. New York: Shirmer Books. ISBN 0-02-871650-7. http://books.google.com/books?id=y9PBAAAACAAJ.

- Williams, Martin (1959). The Art of Jazz: Ragtime to Bebop. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0306801345. http://books.google.com/books?id=VTIJAAAACAAJ.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Scott Joplin |

- The Scott Joplin International Ragtime Foundation

- Joplin at St. Louis Walk of Fame

- "Perfessor" Bill Edwards plays Joplin, with anecdotes and research.

- Maple Leaf Rag A site dedicated to 100 years of the Maple Leaf Rag.

- The Scott Joplin House - St. Louis, Missouri

[edit] Recordings and sheet music

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net - Free Scores by Joplin

- The Mutopia project has freely downloadable piano scores of several of Joplin's works

- Sheet Music and Covers (includes cover art, comprehensive sheet music selection, and biography)

- Free scores by Scott Joplin in the Werner Icking Music Archive (WIMA)

- Free scores by Scott Joplin in the International Music Score Library Project

- Kunst der Fuge: Scott Joplin - MIDI files (live and piano-rolls recordings)

- Scott Joplin - German site with free sheet music and MIDI files

- John Roache's site has excellent MIDI performances of ragtime music by Joplin and others

- Scott Joplin, Complete Piano Rags, David A Jasen, 1988, ISBN 0-486-25807-6

- Scott Joplin Sheet Music

- Pleasant Moments, 2.1MB. This is a recording of the Connorized piano roll made by Joplin in April 1916, and thought lost until mid-2006.