Diogenes of Sinope

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Western Philosophy Ancient philosophy |

|

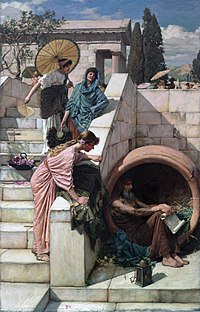

Diogenes by John William Waterhouse, depicting his lamp, tub, and diet of onions. |

|

| Full name | Diogenes (Διογένης ὁ Σινωπεύς) |

|---|---|

| School/tradition | Greek philosophy, Cynicism |

| Main interests | Asceticism, Cynicism |

| Notable ideas | Became the archetypal Cynic philosopher |

|

Influenced by

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Diogenes (Greek: Διογένης ὁ Σινωπεύς Diogenes ho Sinopeus) "the Cynic", Greek philosopher, was born in Sinope (modern day Sinop, Turkey) about 412 BC (according to other sources 404 BC),[1] and died in 323 BC,[2] at Corinth. Details of his life come in the form of anecdotes (chreia), especially from Diogenes Laërtius, in his book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers.

Diogenes of Sinope was exiled from his native city and moved to Athens, where he is said to have become a disciple of Antisthenes, the former pupil of Socrates. Diogenes, a beggar who made his home in the streets of Athens, made a virtue of extreme poverty. He is said to have lived in a large tub, rather than a house, and to have walked through the streets carrying a lamp in the daytime, claiming to be looking for an honest man. He eventually settled in Corinth where he continued to pursue the Cynic ideal of self-sufficiency: a life which was natural and not dependent upon the luxuries of civilization. Believing that virtue was better revealed in action and not theory, his life was a relentless campaign to debunk the social values and institutions of what he saw as a corrupt society.

Contents |

[edit] Life

Diogenes was born in the Greek colony of Sinope on the south coast of the Black Sea, either in 412 BC or 404 BC.[1] Nothing is known about his early life except that his father Hicesias was a banker.[3] It seems likely that Diogenes was also enrolled into the banking business aiding his father. At some point (and the details are confused) Hicesias and Diogenes became embroiled in a scandal involving the adulteration or defacement of the currency,[4] and Diogenes was exiled from the city.[5] This aspect of the story seems to be corroborated by archaeology: large numbers of defaced coins (smashed with a large chisel stamp) have been discovered at Sinope dating from the middle of the 4th century BC, and other coins of the time bear the name of Hicesias as the official who minted them.[6] The reasons for the defacement of the coinage are unclear, although Sinope was being disputed between pro-Persian and pro-Greek factions in the 4th century, and there may have been political rather than financial motives behind the act.

According to one story,[5] Diogenes went to the Oracle at Delphi to ask for its advice, and was told that he should "deface the currency," and Diogenes, realizing that the oracle meant that he should deface the political currency rather than actual coins, travelled to Athens and made it his life's goal to deface established customs and values.

[edit] In Athens

In his new home, Athens, Diogenes' mission became the metaphorical adulterating/defacing of the "coinage" of custom. Custom, he alleged, was the false coin of human morality. Instead of being troubled by what is really evil, people make a big fuss over what is merely conventionally evil. This distinction between nature ("physis") and custom ("nomos") is a favorite theme of ancient Greek philosophy, and one that Plato takes up in The Republic, in the legend of the Ring of Gyges.[7]

Diogenes is alleged to have gone to Athens with a slave named Manes who abandoned him shortly thereafter. With characteristic humour, Diogenes dismissed his ill fortune by saying, "If Manes can live without Diogenes, why not Diogenes without Manes?"[8] Diogenes would be consistent in making fun of such a relation of extreme dependency. He would particularly find the master, who could do nothing for himself, contemptibly helpless. We are told he was attracted by the ascetic teaching of Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, who (according to Plato) had been present at his death.[9] Diogenes became Antisthenes' pupil, despite the brutality with which he was initially received,[10] and rapidly surpassed his master both in reputation and in the austerity of his life. Unlike the other citizens of Athens, he avoided earthly pleasures. This attitude was grounded in a great disdain for what he perceived as the folly, pretense, vanity, social climbing, self-deception, and artificiality of much human conduct.

The stories told of Diogenes illustrate the logical consistency of his character. He inured himself to the vicissitudes of weather by living in a tub belonging to the temple of Cybele.[11] He destroyed the single wooden bowl he possessed on seeing a peasant boy drink from the hollow of his hands.[12] He once masturbated in the Agora; when rebuked for doing so, he replied, "If only it was as easy to soothe my hunger by rubbing my belly."[13] He used to stroll about in full daylight with a lamp; when asked what he was doing, he would answer, "I am just looking for a human being."[14] Diogenes looked for a human being but reputedly found nothing but rascals and scoundrels.[15]

When Plato gave Socrates' definition of man as "featherless bipeds" and was much praised for the definition, Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato's Academy, saying, "Behold! I've brought you a man." After this incident, "with broad flat nails" was added to Plato's definition.[16]

[edit] In Corinth

According to a story which seems to have originated with Menippus of Gadara,[17] Diogenes was once on a voyage to Aegina, he was captured by pirates and sold as a slave in Crete to a Corinthian named Xeniades. Being asked his trade, he replied that he knew no trade but that of governing men, and that he wished to be sold to a man who needed a master. As tutor to Xeniades' two sons,[18] he lived in Corinth for the rest of his life, which he devoted entirely to preaching the doctrines of virtuous self-control.

At the Isthmian Games, he lectured to large audiences.[19] It may have been at one of these festivals that he met Alexander the Great. The story goes that while Diogenes was relaxing in the sunlight one morning, Alexander, thrilled to meet the famous philosopher, asked if there was any favour he might do for him. Diogenes replied, "Yes: Stand out of my sunlight."[20] Alexander still declared, "If I were not Alexander, then I should wish to be Diogenes."[21] In another account, Alexander found the philosopher looking attentively at a pile of human bones. Diogenes explained, "I am searching for the bones of your father but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave."[22]

Although most of the stories about him living in a tub are located in Athens, there are some accounts of him living in a tub near the Craneum gymnasium in Corinth:

A report that Philip was marching on the town had thrown all Corinth into a bustle; one was furbishing his arms, another wheeling stones, a third patching the wall, a fourth strengthening a battlement, every one making himself useful somehow or other. Diogenes having nothing to do - of course no one thought of giving him a job - was moved by the sight to gather up his philosopher's cloak and begin rolling his tub-dwelling energetically up and down the Craneum; an acquaintance asked for, and got, the explanation: "I do not want to be thought the only idler in such a busy multitude; I am rolling my tub to be like the rest."[23]

[edit] Death

There are numerous accounts of Diogenes' death. He is alleged variously to have held his breath;[24] to have become ill from eating raw octopus;[25] or to have suffered an infected dog bite.[26] When asked how he wished to be buried, he left instructions to be thrown outside the city wall so wild animals could feast on his body. When asked if he minded this, he said, "Not at all, as long as you provide me with a stick to chase the creatures away!" When asked how he could use the stick since he would lack awareness, he replied "If I lack awareness, then why should I care what happens to me when I am dead?"[27] At the end, Diogenes made fun of people's excessive concern with the "proper" treatment of the dead. The Corinthians erected to his memory a pillar on which rested a dog of Parian marble.[28]

[edit] Ideas

Along with Antisthenes and Crates of Thebes, Diogenes is considered one of the founders of Cynicism (see Dog theme). The ideas of Diogenes, like those of most other Cynics, must be arrived at indirectly. No writings of Diogenes survived even though he is reported to have authored a number of books.[29] Cynic ideas are inseparable from Cynic practice; therefore what we know about Diogenes is contained in anecdotes concerning his life and sayings attributed to him in a number of scattered classical sources. None of these sources is definitive and all contribute to a "tradition" that should not be confused with factual biography.

It is not known, for example, whether Diogenes made a virtue of naked survival out of necessity or whether he really preferred poverty and homelessness. In any case, Diogenes did "make a case" for benefits of a reduced lifestyle. He apparently proved to the satisfaction of the Stoics who came after him that happiness has nothing whatever to do with a person's material circumstances. The Stoics developed this theme, but made it benign. Epictetus, for example, preached the virtue of modesty and inoffensiveness, but maintained that misfortune is good for the development of strong character.

Diogenes maintained that all the artificial growths of society were incompatible with happiness and that morality implies a return to the simplicity of nature. So great was his austerity and simplicity that the Stoics would later claim him to be a wise man or "sophos". In his words, "Humans have complicated every simple gift of the gods."[30] Although Socrates had previously identified himself as belonging to the world, rather than a city,[31] Diogenes is credited with the first known use of the word "cosmopolitan". When he was asked where he came from, he replied, "I am a citizen of the world (cosmopolites)".[32] This was a radical claim in a world where a man's identity was intimately tied to his citizenship in a particular city state. An exile and an outcast, a man with no social identity, Diogenes made a mark on his contemporaries. His story, however uncertain the details, continues to fascinate students of human nature.

Diogenes was a self-appointed public scold whose mission was to demonstrate to the ancient Greeks that civilization is regressive. He taught by living example that wisdom and happiness belong to the man who is independent of society. Diogenes scorned not only family and political social organization, but property rights and reputation. The most shocking feature of his philosophy is his rejection of normal ideas about human decency. Exhibitionist and philosopher, Diogenes is said to have eaten[33] (and once masturbated)[13] in the marketplace, urinated on some people who insulted him,[34] defecated in the theatre,[35] and pointed at people with his middle finger.[36] Sympathizers considered him a devotee of reason and an exemplar of honesty. Detractors have said he was an obnoxious beggar and an offensive grouch.

Despite having apparently nothing but disdain for Plato and his abstract philosophy,[37] Diogenes bears striking resemblance to the character of Socrates. He shared Socrates' belief that he could function as doctor to men's souls and improve them morally, while at the same time holding contempt for their obtuseness. Plato once described Diogenes as "a Socrates gone mad."[38]

[edit] Dog theme

Many anecdotes of Diogenes refer to his dog-like behavior, and his praise of a dog's virtues. It is not known whether Diogenes was insulted with the epithet "doggish" and made a virtue of it, or whether he first took up the dog theme himself. The modern terms cynic and cynical derive from the Greek word kynikos, the adjective form of kyon, meaning dog.[39] Diogenes believed human beings live artificially and hypocritically and would do well to study the dog. Besides performing natural bodily functions in public without unease, a dog will eat anything, and make no fuss about where to sleep. Dogs live in the present without anxiety, and have no use for the pretensions of abstract philosophy. In addition to these virtues, dogs are thought to know instinctively who is friend and who is foe. Unlike human beings who either dupe others or are duped, dogs will give an honest bark at the truth.

As noted (see Death), Diogenes' association with dogs was memorialized by the Corinthians, who erected to his memory a pillar on which rested a dog of Parian marble.[40]

[edit] Art and popular culture

Both in ancient and in modern times, his personality has appealed strongly to sculptors and to painters. Ancient busts exist in the museums of the Vatican, the Louvre, and the Capitol. The interview between Diogenes and Alexander is represented in an ancient marble bas-relief found in the Villa Albani. Rubens, Jordaens, Steen, Van der Werff, Jeaurat, Salvator Rosa, Nicolas Poussin, Karel Dujardin, and Castiglione have painted scenes from his life. Also, in Raphael's fresco The School of Athens in the papal apartments, a lone solitary figure in the foreground represents Diogenes. This figure is widely purported to be a portrait of Michelangelo, another famously solitary figure, who was at the time painting the vault of the Sistine Chapel.[41]

Diogenes is referred to in Anton Chekhov's story Ward No. 6; William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; Francois Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel; as well as in the first sentence of Søren Kierkegaard's novelistic treatise Repetition. He is the primary model for the philosopher Dydactylos in Terry Prachett's Small Gods. He is mimicked by a beggar-spy in Jacqueline Carey's Kushiel's Scion and paid tribute to with a costume in a party by the main character in its sequel, Kushiel's Justice. The character Lucy Snowe in Charlotte Bronte's novel Villette is given the nickname Diogenes. Diogenes also features in Part Four of Elizabeth Smart's By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. He is a figure in Seamus Heaney's The Haw Lantern. In Christopher Moore's Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal, one of Jesus' apostles is a devotee of Diogenes, complete with his own pack of dogs which he refers to as his own disciples.

His story opens the first chapter of Dolly Freed's 1978 book "Possum Living".

He appears in the animated series Reign: the Conqueror where he plays a more pivotal role in the life of Alexander the Great. He is referenced in the eleventh episode of Kino's Journey.

He is mentioned in the songs "The Modern Adventures of Plato, Diogenes and Freud" by Blood, Sweat & Tears, "Start Wearing Purple" by Gogol Bordello, "Get Off" by Bad Religion, "To Lanterns, Denver, and One Last Lament" by Defiance, Ohio, "Oh, Diogenes!" from the Rodgers and Hart musical The Boys From Syracuse, and "Socrates" by Aardvark Spleen.

A homeless man, Edwin McKenzie, who was nicknamed Diogenes, was befriended by the artist Robert Lenkiewicz. Lenkiewicz embalmed his friend's body after his death, and controversy resulted after the body was discovered in the artist's studio.[42]

[edit] The Diogenes Club

The philosopher's name was adopted by the fictional Diogenes Club, an organization that Sherlock Holmes' brother Mycroft Holmes belongs to in the story The Greek Interpreter by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It is called such as its members are educated, yet untalkative and have a dislike of socialising, much like the philosopher himself. The group is the focus of a number of Holmes pastiches by Kim Newman.

[edit] Diogenes Syndrome

Diogenes' name has been applied to a behavioural disorder characterised by involuntary self-neglect and hoarding.[43] The disorder afflicts the elderly and has no relation to Diogenes' deliberate Herculean rejection of material comfort.[44] Notable sufferers included Edmund Trebus.

[edit] Diogenes and modern theory

Diogenes is discussed in a 1983 book by German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk (English language publication in 1987). In his Critique of Cynical Reason, Diogenes is used as an example of Sloterdijk’s idea of the “kynical” — in which personal degradation is used for purposes of community comment or censure. Calling the practice of this tactic “kynismos,” Sloterdijk explains that the kynical actor actually embodies the message he/she is trying to convey. The goal here is typically a false regression that mocks authority — especially authority that the kynical actor considers corrupt, suspect, or unworthy.

There is another discussion of Diogenes and the Cynics in Michel Foucault's book Fearless Speech. Here Foucault discusses Diogenes' antics in relation to the speaking of truth (parrhesia) in the ancient world.

[edit] Notes

- ^ a b He is said to have died 323 BC. Diogenes Laërtius (vi. 76) says he died "nearly 90", i.e, he was born c. 412 BC. But Censorinus (De die natali, 15.2) says he died aged 81, and the Suda puts his birth at the time of the Thirty Tyrants, i.e., 404 BC.

- ^ Supposedly on the same day as Alexander the Great: Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 79, Plutarch, Moralia, 717c.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 20. A trapezites was a banker/money-changer who could exchange currency, arrange loans, and was sometimes entrusted with the minting of currency.

- ^ Navia, Diogenes the Cynic, pg 226: "The word paracharaxis can be understood in various ways such as the defacement of currency or the counterfeiting of coins or the adulteration of money."

- ^ a b Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 20, 21.

- ^ C. T. Seltman, Diogenes of Sinope, Son of the Banker Hikesias, in Transactions of the International Numismatic Congress 1936 (London 1938).

- ^ Plato, Republic, 2.359-2.360.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 55.; Seneca, De Tranquillitate Animi, 8.7.; Aelian, Varia Historia, 13.28.

- ^ Plato, Phaedo, 59 b.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 21.; Aelian, Varia Historia, 10.16.; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 23.; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 37.; Seneca, Epistles, 90.14.; Jerome, Adversus Jovinianum, 2.14.

- ^ a b Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 46, 69; Dio Chrysostom, Or. 6.16-20

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 41. Modern sources often say that Diogenes was looking for an "honest man", but in ancient sources he is simply looking for a "human" (anthrôpos). The unreasoning behavior of the people around him means that they do not qualify as human.

- ^ Cf. Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 32

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 40.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 29.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 30, 31.

- ^ Dio Chrysostom, Or. 8.10

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 38.; Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 5.32.; Plutarch, Alexander, 14, On Exile, 15; Dio Chrysostom, Or. 4.14

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 32.; Plutarch, Alexander, 14, On Exile, 15.

- ^ This rather odd story, which appears frequently in books from the 16th to the 19th century, may be an example of an anecdote invented about Diogenes in modern times. There is a similar anecdote in one of the dialogues of Lucian (Menippus, 15) but that story concerns Menippus in the underworld.

- ^ Lucian, Historia, 3.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 76. It is, of course, impossible to die from holding your breath.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 76.; Athenaeus, 8.341.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 77.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 1.42.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 78.; Greek Anthology, 1.285.; Pausanias, 2.2.4.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 80.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 44.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 5.37.; Plutarch, On Exile, 5.; Epictetus, Discourses, i.9.1.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 63. Compare: Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 72, Dio Chrysostom, Or. 4.13, Epictetus, Discourses, iii.24.66.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 58, 69. Eating in public places was considered bad manners.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 46.

- ^ Dio Chrysostom, Or. 8.36; Julian, Orations, 6.202c.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 34, 35; Epictetus, Discourses, iii.2.11. Pointing with one's middle finger was considered insulting; with the finger pointing up instead of to another person, the finger gesture is considered obscene in modern times.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 24.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 54; Aelian, Varia Historia, 14.33.

- ^ Liddell, H. G.; Scott, R.: A Greek-English Lexicon

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, vi. 78.; Greek Anthology, 1.285.; Pausanias, 2.2.4.

- ^ Michelangelo and the Pope's Ceiling, by Ross King

- ^ BBC News [1]

- ^ Hanon C, Pinquier C, Gaddour N, Saïd S, Mathis D, Pellerin J (2004). "[Diogenes syndrome: a transnosographic approach]" (in French). Encephale 30 (4): 315–22. PMID 15538307. http://www.masson.fr/masson/MDOI-ENC-9-2004-30-4-0013-7006-101019-ART2.

- ^ Navia, Diogenes the Cynic, pg 31

[edit] References

- Diogenes Laërtius (1972). Lives of eminent philosophers. 2. translated by RD Hicks. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-99204-0.

- Navia, Luis E. (2005). Diogenes The Cynic: The War Against The World. Amherst, N.Y: Humanity Books. ISBN 1-59102-320-3.

- Herakleitos & Diogenes. translated by Guy Davenport. Bolinas [Calif.]: Grey Fox Press. 1979. ISBN 0-912516-36-4.

(Contains 124 sayings of Diogenes loosely translated from Diogenes Laërtius and Plutarch.) - Sloterdijk, Peter (1987). Critique of cynical reason. Translation by Michael Eldred; foreword by Andreas Huyssen. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1586-1.

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Diogenes of Sinope |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Diogenes of Sinope |

- Diogenes of Sinope, by Diogenes Laërtius, translated by C.D. Yonge

- Diogenes of Sinope entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Diogenes The Dog from Millions of Mouths

- Diogenes of Sinope

- A day with Diogenes

- Teachings of Diogenes

- James Grout: Diogenes the Cynic, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Possum Living by Dolly Freed

- Diogenes of Sinope