Organelle

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In cell biology, an organelle (pronunciation: /ɔː(r)gəˡnɛl/) is a specialized subunit within a cell that has a specific function, and is usually separately enclosed within its own lipid membrane.

The name organelle comes from the idea that these structures are to cells what an organ is to the body (hence the name organelle, the suffix -elle being a diminutive). Organelles are identified by microscopy, and can also be purified by cell fractionation. There are many types of organelles, particularly in the eukaryotic cells of higher organisms. Prokaryotes were once thought not to have organelles, but some examples have now been identified.[1]

Contents |

[edit] History and Terminology

In biology, an organ is defined as a confined functional unit within an organism. The analogy of bodily organs to microscopic cellular substructures is obvious, as from even early works, authors of respective textbooks rarely elaborate on the distinction between the two.

Credited as the first[2][3][4] to use a diminutive of organ (i.e. little organ) for cellular structures was German zoologist Karl August Möbius (1884), who used the term "organula" [5] (plural form of organulum, the diminutive of latin organum). From the context, it is clear that he referred to reproduction related structures of protists. In a footnote, which was published as a correction in the next issue of the journal, he justified his suggestion to call organs of unicellular organisms "organella" since they are only differently formed parts of one cell, in contrast to multicellular organs of multicellular organisms. Thus, the original definition was limited to structures of unicellular organisms.

It would take several years before organulum, or the later term organelle, became accepted and expanded in meaning to include subcellular structures in multicellular organisms. Books around 1900 from Valentin Häcker,[6] Edmund Wilson[7] and Oscar Hertwig[8] still referred to cellular organs. Later, both terms came to be used side by side: Bengt Lidforss wrote 1915 (in German) about "Organs or Organells".[9]

Around 1920, the term organelle was used to describe propulsion structures ("motor organelle complex", i.e., flagella and their anchoring)[10] and other protist structures, such as ciliates.[11] Alfred Kühn wrote about centrioles as division organelles, although he stated that, for Vahlkampfias, the alternative 'organelle' or 'product of structural build-up' had not yet been decided, without explaining the difference between the alternatives.[12]

In his 1953 textbook, Max Hartmann used the term for extracellular (pellicula, shells, cell walls) and intracellular skeletons of protists.[13]

Later, the now-widely-used[14][15][16][17] definition of organelle emerged, after which only cellular structures with surrounding membrane had been considered organelles. However, the more original definition of subcellular functional unit in general still coexists.[18][19]

In 1978, Albert Frey-Wyssling suggested that the term organelle should refer only to structures that convert energy, such as centrosomes, ribosomes, and nucleoli.[20][21] This new definition, however, did not win wide recognition.

[edit] Examples

While most cell biologists consider the term organelle to be synonymous with "cell compartment," other cell biologists choose to limit the term organelle to include only those that are DNA-containing, having originated from formerly-autonomous microscopic organisms acquired via endosymbiosis.[22][23][24]

The most notable of these organelles having originated from endosymbiont bacteria are:

- mitochondria (in almost all eukaryotes)

- chloroplasts (in plants, algae and protists).

Other organelles are also suggested to have endosymbiotic origins, (notably the flagellum - see evolution of flagella).

Not all parts of the cell qualify as organelles, and the use of the term to refer to some structures is disputed. These structures are large assemblies of macromolecules that carry out particular and specialized functions, but they lack membrane boundaries. Such cell structures, which are not formally organelles, include:

[edit] Eukaryotic organelles

Eukaryotes are one of the most structurally complex cell type, and by definition are in part organized by smaller interior compartments, that are themselves enclosed by lipid membranes that resemble the outermost cell membrane. The larger organelles, such as the nucleus and vacuoles, are easily visible with the light microscope. They were among the first biological discoveries made after the invention of the microscope.

Not all eukaryotic cells have every one of the organelles listed below. Exceptional organisms have cells which do not include some organelles that might otherwise be considered universal to eukaryotes (such as mitochondria).[25] There are also occasional exceptions to the number of membranes surrounding organelles, listed in the tables below (e.g., some that are listed as double-membrane are sometimes found with single or triple membranes). In addition, the number of individual organelles of each type found in a given cell varies depending upon the function of that cell.

| Organelle | Main function | Structure | Organisms | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chloroplast (plastid) | photosynthesis | double-membrane compartment | plants, protists (rare kleptoplastic organisms) | has some genes; theorized to be engulfed by the ancestral eukaryotic cell (endosymbiosis) |

| endoplasmic reticulum | translation and folding of new proteins (rough endoplasmic reticulum), expression of lipids (smooth endoplasmic reticulum) | single-membrane compartment | all eukaryotes | rough endoplasmic reticulum is covered with ribosomes, has folds that are flat sacs; smooth endoplasmic reticulum has folds that are tubular |

| Golgi apparatus | sorting and modification of proteins | single-membrane compartment | all eukaryotes | cis-face (convex) nearest to rough endoplasmic reticulum; trans-face (concave) farthest from rough endoplasmic reticulum |

| mitochondrion | energy production | double-membrane compartment | most eukaryotes | has some DNA; theorized to be engulfed by the ancestral eukaryotic cell (endosymbiosis) |

| vacuole | storage, homeostasis | single-membrane compartment | eukaryotes | |

| nucleus | DNA maintenance, RNA transcription | double-membrane compartment | all eukaryotes | has bulk of genome |

Mitochondria and chloroplasts, which have double-membranes and their own DNA, are believed to have originated from incompletely consumed or invading prokaryotic organisms, which were adopted as a part of the invaded cell. This idea is supported in the Endosymbiotic theory.

| Organelle/Macromolecule | Main function | Structure | Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| acrosome | helps spermatoza fuse with ovum | single-membrane compartment | many animals |

| autophagosome | vesicle which sequesters cytoplasmic material and organelles for degradation | double-membrane compartment | all eukaryotic cells |

| centriole | anchor for cytoskeleton | Microtubule protein | animals |

| cilium | movement in or of external medium; "critical developmental signaling pathway"[26]. | Microtubule protein | animals, protists, few plants |

| glycosome | carries out glycolysis | single-membrane compartment | Some protozoa, such as Trypanosomes. |

| glyoxysome | conversion of fat into sugars | single-membrane compartment | plants |

| hydrogenosome | energy & hydrogen production | double-membrane compartment | a few unicellular eukaryotes |

| lysosome | breakdown of large molecules (e.g., proteins + polysaccharides) | single-membrane compartment | most eukaryotes |

| melanosome | pigment storage | single-membrane compartment | animals |

| mitosome | not characterized | double-membrane compartment | a few unicellular eukaryotes |

| myofibril | muscular contraction | bundled filaments | animals |

| nucleolus | ribosome production | protein-DNA-RNA | most eukaryotes |

| parenthesome | not characterized | not characterized | fungi |

| peroxisome | breakdown of metabolic hydrogen peroxide | single-membrane compartment | all eukaryotes |

| ribosome | translation of RNA into proteins | RNA-protein | eukaryotes, prokaryotes |

| vesicle | material transport | single-membrane compartment | all eukaryotes |

Other related structures:

[edit] Prokaryotic organelles

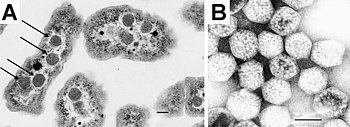

Prokaryotes are not as structurally complex as eukaryotes, and were once thought not to have any internal structures enclosed by lipid membranes. In the past, they were often viewed as having little internal organization; but, slowly, details are emerging about prokaryotic internal structures. An early false turn was the idea developed in the 1970s that bacteria might contain membrane folds termed mesosomes, but these were later shown to be artifacts produced by the chemicals used to prepare the cells for electron microscopy.[28]

However, more recent research has revealed that at least some prokaryotes have microcompartments such as carboxysomes. These subcellular compartments are 100 - 200 nm in diameter and are enclosed by a shell of proteins.[1] Even more striking is the description of membrane-bound magnetosomes in bacteria,[29][30] as well as the nucleus-like structures of the Planctomycetes that are surrounded by lipid membranes.[31]

| Organelle/Macromolecule | Main function | Structure | Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| carboxysome | carbon fixation | protein-shell compartment | some bacteria |

| chlorosome | photosynthesis | light harvesting complex | green sulfur bacteria |

| flagellum | movement in external medium | protein filament | some prokaryotes and eukaryotes |

| magnetosome | magnetic orientation | inorganic crystal, lipid membrane | magnetotactic bacteria |

| nucleoid | DNA maintenance, transcription to RNA | DNA-protein | prokaryotes |

| plasmid | DNA exchange | circular DNA | some bacteria |

| ribosome | translation of RNA into proteins | RNA-protein | eukaryotes, prokaryotes |

| thylakoid | photosynthesis | photosystem proteins and pigments | mostly cyanobacteria |

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ a b Kerfeld, Ca; Sawaya, Mr; Tanaka, S; Nguyen, Cv; Phillips, M; Beeby, M; Yeates, To (August 2005). "Protein structures forming the shell of primitive bacterial organelles.". Science (New York, N.Y.) 309 (5736): 936–8. doi:. PMID 16081736.

- ^ Bütschli, O. (1888). Dr. H. G. Bronn's Klassen u. Ordnungen des Thier-Reichs wissenschaftlich dargestellt in Wort und Bild. Erster Band. Protozoa. Dritte Abtheilung: Infusoria und System der Radiolaria.. pp. 1412. "Die Vacuolen sind demnach in strengem Sinne keine beständigen Organe oder O r g a n u l a (wie Möbius die Organe der Einzelligen im Gegensatz zu denen der Vielzelligen zu nennen vorschlug)."

- ^ Amer. Naturalist. 23, 1889, S. 183: „It may possibly be of advantage to use the word organula here instead of organ, following a suggestion by Möbius. Functionally-differentiated multicellular aggregates in multicellular forms or metazoa are in this sense organs, while, for functionally-differentiated portions of unicellular organisms or for such differentiated portions of the unicellular germ-elements of metazoa, the diminutive organula is appropriate.“ Cited after : Oxford English Dictionary online, entry for „organelle“.

- ^ 'Journal de l'anatomie et de la physiologie normales et pathologiques de l'homme et des animaux' at Google Books

- ^ Möbius, K. (September 1884). "Das Sterben der einzelligen und der vielzelligen Tiere. Vergleichend betrachtet". Biologisches Centralblatt 4 (13,14): 389–392, 448. http://www.dietzellab.de/goodies/history/. "Während die Fortpflanzungszellen der vielzelligen Tiere unthätig fortleben bis sie sich loslösen, wandern und entwickeln, treten die einzelligen Tiere auch durch die an der Fortpflanzung beteiligten Leibesmasse in Verkehr mit der Außenwelt und viele bilden sich dafür auch besondere Organula." Footnote on p. 448: "Die Organe der Heteroplastiden bestehen aus vereinigten Zellen. Da die Organe der Monoplastiden nur verschieden ausgebildete Teile e i n e r Zelle sind schlage ich vor, sie „Organula“ zu nennen".

- ^ Häcker, Valentin (1899). Zellen- und Befruchtungslehre. Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fisher.

- ^ Wilson, Edmund B. (1900). The cell in Development and Inheritance (second ed.). New York: The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Hertwig, Oscar (1906). Allgemeine Biologie. Zweite Auflage des Lehrbuchs „Die Zelle und die Gewebe“. Jena: Verlag von Gustav Fischer.

- ^ Lidforss, B. (1915). "Protoplasma". in Paul Hinneberg. Allgemeine Biologie. Leipzig, Berlin: Verlag von B.G.Teubner. pp. 227 (218–264). "Eine Neubildung dieser Organe oder Organellen findet wenigstens bei höheren Pflanzen nicht statt"

- ^ Kofoid CA, Swezy O (1919). "Flagellate Affinities of Trichonympha". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 5 (1): 9–16. doi:. PMID 16576345.

- ^ Cl. Hamburger, Handwörterbuch der Naturw. Bd. V, .S. 435. Infusorien. cited after Petersen, Hans (1919). "Über den Begriff des Lebens und die Stufen der biologischen Begriffsbildung". Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen (now: Development Genes and Evolution) 45 (3): 423–442. doi:.

- ^ Kühn, Alfred (1920). "Untersuchungen zur kausalen Analyse der Zellteilung. I. Teil: Zur Morphologie und Physiologie der Kernteilung von Vahlkampfia bistadialis". Archiv für Entwicklungsmechanik der Organismen (now: Development Genes and Evolution) 46: 259–327. doi:. "die Alternative: Organell oder Produkt der Strukturbildung".

- ^ Hartmann, Max (1953). Allgemeine Biologie (4. Aufl. ed.). Stuttgart: Gustav Fisher Verlag.

- ^ Nultsch, Allgemeine Botanik, 11. Aufl. 2001, Thieme Verlag

- ^ Wehner/Gehring, Zoologie, 23. Aufl. 1995, Thieme Verlag

- ^ Alberts et al., Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4. ed. 2002, online via "NCBI-Bookshelf"

- ^ Brock, Mikrobiologie, 2. korrigierter Nachdruck (2003), der 1. Aufl. von 2001

- ^ Strasburgers Lehrbuch der Botanik für Hochschulen, 35. Aufl. (2002), S. 42

- ^ Alliegro MC, Alliegro MA, Palazzo RE (June 2006). "Centrosome-associated RNA in surf clam oocytes". Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 103 (24): 9034–9038. doi:. PMID 16754862.

- ^ Frey-Wyssling, A (1978). "Definition of the organell concept" (in German). Gegenbaurs morphologisches Jahrbuch 124 (3): 455–7. ISSN 0016-5840. PMID 689352.

- ^ Albert Frey-Wyssling: Concerning the concept "Organelle". Experientia 34, 547 (1978). doi:10.1007/BF01935984

- ^ Keeling, Pj; Archibald, Jm (April 2008). "Organelle evolution: what's in a name?". Current biology : CB 18 (8): R345–7. doi:. PMID 18430636. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6VRT-4SB9SNV-K&_user=5731894&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=5731894&md5=2f16ed5ee031ea9cdce4f7e2a934a8fa. Retrieved on 2008-08-07.

- ^ Imanian B, Carpenter KJ, Keeling PJ (March 2007). "Mitochondrial genome of a tertiary endosymbiont retains genes for electron transport proteins.". The Journal of eukaryotic microbiology 54 (2): 146–53. doi:. PMID 17403155. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/118000427/HTMLSTART.

- ^ Mullins, Christopher (2004). "Theory of Organelle Biogenesis: A Historical Perspective". The Biogenesis of Cellular Organelles. Springer Science+Business Media, National Institutes of Health.

- ^ Fahey RC, Newton GL, Arrack B, Overdank-Bogart T, Baley S (1984). "Entamoeba histolytica: a eukaryote without glutathione metabolism". Science 224 (4644): 70–72. doi:. PMID 6322306.

- ^ Badano, Jose L.; Norimasa Mitsuma, Phil L. Beales, Nicholas Katsanis (September 2006). "The Ciliopathies : An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders". Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 7: 125–148. doi:. http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

- ^ Tsai Y, Sawaya MR, Cannon GC, Cai F, Williams EB, Heinhorst S, Kerfeld CA, Yeates TO (Jun 2007). "Structural analysis of CsoS1A and the protein shell of the Halothiobacillus neapolitanus carboxysome." (Free full text). PLoS biology 5 (6): e144. doi:. PMID 17518518. PMC: 1872035. http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0050144.

- ^ Ryter A (1988). "Contribution of new cryomethods to a better knowledge of bacterial anatomy". Ann. Inst. Pasteur Microbiol. 139 (1): 33–44. doi:. PMID 3289587.

- ^ Komeili A, Li Z, Newman DK, Jensen GJ (2006). "Magnetosomes are cell membrane invaginations organized by the actin-like protein MamK". Science 311 (5758): 242–5. doi:. PMID 16373532.

- ^ Scheffel A, Gruska M, Faivre D, Linaroudis A, Plitzko JM, Schüler D (2006). "An acidic protein aligns magnetosomes along a filamentous structure in magnetotactic bacteria". Nature 440 (7080): 110–4. doi:. PMID 16299495.

- ^ Fuerst JA (2005). "Intracellular compartmentation in planctomycetes". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59: 299–328. doi:. PMID 15910279.

[edit] Bibliography

- Alberts, Bruce et al. (2003). Essential Cell Biology, 2nd ed., Garland Science, 2003, ISBN 081533480X.

- Alberts, Bruce et al. (2002). The Molecular Biology of the Cell, 4th ed., Garland Science, 2002, ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

[edit] External Links

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||