Kensington Runestone

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Kensington Runestone | |

|

|

| Name | Kensington Runestone |

|---|---|

| Country | USA |

| Region | Minnesota |

| City/Village | Originally Kensington currently located at Alexandria, Minnesota |

| Produced | contested |

| Runemaster | contested |

| Text - Native | |

| direct transliteration (Swedish dialect)

8 göter ok 22 norrmen po ??o opdagelsefard fro vinland of vest. vi hade läger ved 2 skelar en dags rise norr fro deno sten. vi var ok fiske en dagh, äptir vi kom hem fan 10 man røde af blod og ded. AVM frälse af illu. |

|

| Text - English | |

| (word-for-word): 8 Geats/Goths/Gutnish/Gotlanders and 22 Norwegians/Northmen on a? discovery/seeking expedition, from Vinland west of. We had a camp with 2 shelters, one day's journey north from this stone. We were at fishing one day, after we came home found 10 men red of blood and dead. AVM (Ave Virgo Maria[1]) rescue from evils. [side of stone] Have 10 men by/at sea to look after our ship, 14 day journey from this island. Year 1362. |

|

| Other resources | |

| Runestones - Runic alphabet Runology - Runestone styles |

|

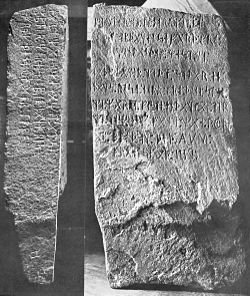

The Kensington Runestone is a slab of greywacke covered in runes on its face and side which, if it is genuine, would suggest that Scandinavian explorers reached the middle of North America in the 14th century. It was found in 1898 in the largely rural township of Solem, Douglas County, Minnesota, and named after the nearest settlement, Kensington. Most runologists and linguists consider the runestone to be a hoax.[2] The runestone has been analysed and dismissed repeatedly without local effect.[3][4][5][6][7] The community of Kensington is solidly behind the runestone, which has transcended its original cultural purposes and has "taken on a life of its own".[8][9]

Contents |

[edit] Provenance

Swedish American farmer Olof Öhman said he found the stone late in 1898 while clearing his land of trees and stumps before plowing, having recently taken over a plot which had for years been left unallocated as "Internal Improvement Land"[10]. The stone was said to be near the crest of a small knoll rising above the wetlands, lying face down and tangled in the root system of a stunted poplar tree, estimated to be about from less than 10 to about 40 years old.[11] Unfortunately, there were no non-family witnesses to grubbing of the tree and the stone said to have been in the roots. People who later saw the cut roots said that some of the roots were flattened and were consistent with having held a stone. Öhman's ten-year-old son noticed some markings and the farmer later said he thought they'd found an "Indian almanac." The artifact is about 30 x 16 x 6 inches (76 x 41 x 15 cm) in size and weighs about 200 pounds (90 kg). Unfortunately, there are many different versions describing when the stone was found -- August or November, right after lunch or near the end of work for the evening -- who discovered the stone -- Öhman and his son; Öhman, his son and two workmen; Öhman, his son, and his neighbor Nils Flaten, and when the stone was taken to the nearby town of Kensington and who made the first inscriptions that were sent to a regional Scandinavian language newspaper.

When Öhman discovered the stone, the journey of Leif Ericson to Vinland (North America) was being widely discussed and there was renewed interest in the Vikings throughout Scandinavia, stirred by the National Romanticism movement. Five years earlier a Danish archaeologist had proved it was possible to travel to North America in medieval ships. There was also friction between Sweden and Norway (which ultimately led to Norway's independence from Sweden in 1905). Some Norwegians claimed the stone was a Swedish hoax and there were similar Swedish accusations because the stone is inscribed with a reference to a joint expedition of Norwegians and Swedes at a time when they were both ruled by the same king. More locally, Scandinavians were newcomers in Minnesota, still struggling for acceptance; the runestone took root in a community that was proud of its Scandinavian heritage.[12]

Soon after it was found, the stone was displayed at a local bank. There is no evidence Öhman tried to make money from his find. An error-ridden copy of the inscription made its way to the Greek language department at the University of Minnesota, then to Olaus J. Breda, a professor of Scandinavian languages and literature there from 1884 to 1899, who showed little interest in the find and whose runic knowledge was later questioned by some researchers. Breda made a translation, declared it to be a forgery and forwarded copies to linguists in Scandinavia. Norwegian archaeologist Oluf Rygh also concluded the stone was a fraud, as did several other linguists.

By now the stone had been sent to Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. With scholars either dismissing it as a prank or unable to identify a sustainable historical context, it was returned to Öhman, who is said to have placed it face down near the door of his granary as a "stepping stone" which he also used for straightening out nails (years later his son said this was an "untruth" and that they had it set up in an adjacent shed, but he appears to have been referring only to the way the stone was treated before it started to attract interest at the end of 1898). In 1907 the stone was purchased, reportedly for ten dollars, by Hjalmar Holand, a former graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Holand created renewed public interest with an article[13] enthusiastically summarizing studies that were made by geologist Newton Horace Winchell (Minnesota Historical Society) and linguist George T. Flom (Philological Society of the University of Illinois), who both published opinions in 1910.[14]

According to Winchell, the tree under which the stone was allegedly found had been destroyed before 1910, but several nearby poplars that witnesses estimated as being about the same size were cut down, and by counting their rings it was determined they were indeed around 30-40 years old (NB: letters were written to members of a team which had excavated at the find site in 1899, and their estimates from memory, without any reference to tree rings, ranged as low as 10-12 years in the case of county schools superintendent Cleve Van Dyke[15]). The surrounding county had not been settled until 1858, and settlement was severely restricted for a time by the Dakota War of 1862 (although it was reported that the best land in the township adjacent to Solem, Holmes City, was already taken by 1867, by a mixture of Swedish, Norwegian and "Yankee" settlers[16]). Winchell also concluded that the weathering of the stone indicated the inscription was roughly 500 years old. Meanwhile, Flom found a strong apparent divergence between the runes used in the Kensington inscription and those in use during the 14th century. Similarly, the language of the inscription was surprisingly modern compared to the Nordic languages of the 14th century.[14]

Most discussions over the Kensington Runestone's authenticity have been based on an apparent conflict between the linguistic and physical evidence. The Runestone's discovery by a Swedish farmer in Minnesota at a time when Viking history and Scandinavian culture were such popular and sometimes controversial topics casts a stark shadow of skepticism that has lingered for more than a hundred years.

The Kensington Runestone is currently on display at the Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota,[17] where "the sign over the entrance, reading 'Alexandria Chamber of Commerce-Runestone Museum-Tourist Information-Douglas County Historical Society-Alexandria Development Corp.' reflects the close association between a version of the past and local business interests," noted Michlovic in 1990.[8]

[edit] Possible historical background

In 1577, cartographer Gerardus Mercator wrote a letter containing the only detailed description of the contents of a geographical text about the Arctic region of the Atlantic, possibly written over two centuries earlier by one Jacob Cnoyen. Cnoyen had learned that in 1364, eight men had returned to Norway from the Arctic islands, one of whom, a priest, provided the King of Norway with a great deal of geographical information.[18] Books by scholars such as Carl Christian Rafn early in the 19th century revealed hints of reality behind this tale. A priest named Ivar Bardarsson, who had previously been based in Greenland, really did turn up in Norwegian records from 1364 onward, and copies of his geographical description of Greenland still survive. Furthermore, in 1354, King Magnus Eriksson of Sweden and Norway had issued a letter appointing a law officer named Paul Knutsson as leader of an expedition to the colony of Greenland, to investigate reports that the population was turning away from Christian culture.[19] Another of the documents reprinted by the 19th century scholars was a scholarly attempt by Icelandic Bishop Gisli Oddsson, in 1637, to compile a history of the Arctic colonies. He dated the Greenlanders' fall away from Christianity to 1342, and claimed that they had turned instead to America. Supporters of a 14th century origin for the Kensington runestone argue that Knutson may therefore have travelled beyond Greenland to North America, in search of renegade Greenlanders, most of his expedition being killed in Minnesota and leaving just the eight voyagers to return to Norway.[20]

However, there is no evidence that the Knutson expedition ever set sail (the government of Norway went through considerable turmoil in 1355) and the information from Cnoyen as relayed by Mercator states specifically that the eight men who came to Norway in 1364 were not survivors of a recent expedition, but descended from the colonists who had settled the distant lands, generations earlier.[18] Also, those early 19th century books, which aroused a great deal of interest among Scandinavian Americans would have been available to a late 19th century hoaxer.

In The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically (2005) archeologist Alice Beck Kehoe alluded to reports of contact between native American populations and outsiders prior to the time of the runestone. These include historical references to the "blond" Indians among the Mandan on the Upper Missouri River, signs of a tuberculosis epidemic among American Indians about 1000 A.D. and the Hochunk (Winnebago) story about an ancestral hero "Red Horn" and his encounter with "red-haired giants."

[edit] Geography

A natural north-south navigation route—admittedly with a number of portages round dangerous rapids—extends from Hudson Bay up Nelson River through Lake Winnipeg, then up the Red River of the North. The northern waterway begins at Traverse Gap, on the other side of which is the source of the Minnesota River, flowing to join the great Mississippi River at Minneapolis. One of the early Runestone debunkers, George Flom, found that explorers and traders had come from Hudson Bay to Minnesota by this route decades before the area was officially settled,[21] but supporters of the stone's authenticity argued that the 1362 party could have used the same waterway.[22]

[edit] Other artifacts?

This waterway also contains alleged signs of Viking presence. At Cormorant Lake in Becker County, Minnesota, there are three boulders with triangular holes which are claimed to be similar to those used for mooring boats along the coast of Norway during the 14th century. Holand found other triangular holes in rocks near where the stone was found; however, experimental archaeology later suggested that holes dug in stone with chisels rather than drills tend to have a triangular cross-section, whatever their purpose.[23] A little further north, by the Red River itself, at Climax, Minnesota, a firesteel found in 1871, buried quite deep in soft ground, matched specimens of medieval Norse firesteels at the Oslo University museum in Norway.[24]

There has also been considerable discussion of what has recently been named the Vérendrye Runestone, a small plaque allegedly found by one of the earliest expeditions along what later became the U.S./Canada border, in the 1730s. "Allegedly", because it is not referred to in the journal of the expedition, or indeed any first-hand source; only in a summary of a conversation about the expedition a decade after it took place.[25]

No non-Native American artifacts dating from before 1492 have been recovered under controlled, professionally conducted archaeological investigations at any great distance from the east coast of the continent; and with current techniques, the dating of any holes cut into rocks in the region is as uncertain as the dating of the Kensington stone itself.

[edit] Debate

Holand took the stone to Europe and, while newspapers in Minnesota carried articles hotly debating its authenticity, the stone was quickly dismissed by Swedish linguists.

For the next 40 years, Holand struggled to sway public and scholarly opinion about the Runestone, writing articles and several books. He achieved brief success in 1949, when the stone was put on display at the Smithsonian Institution, and scholars such as William Thalbitzer and S. N. Hagen published papers supporting its authenticity.[26] However, at nearly the same time, Scandinavian linguists Sven Jansson, Erik Moltke, Harry Anderson and K. M. Nielsen, along with a popular book by Erik Wahlgren again questioned the Runestone's authenticity.[3]

Along with Wahlgren, historian Theodore C. Blegen flatly asserted[4] Öhman had carved the artifact as a prank, possibly with help from others in the Kensington area. Further resolution seemed to come with the 1976 published transcript[5] of an audio tape made by Walter Gran several years earlier. In it, Gran said his father John confessed in 1927 that Öhman made the inscription. John Gran's story however was based on second-hand anecdotes he had heard about Öhman, and although it was presented as a dying declaration, Gran lived for several years afterwards saying nothing more about the stone. In 2005 supporters of the runestone's authenticity attempted to explain this with claims that Gran was motivated by jealousy over the attention Öhman had received.

The possibility of a Scandinavian provenance for the Runestone was renewed in 1982 when Robert Hall, an emeritus Professor of Italian Language and Literature at Cornell University (but a poor runologist; see the negative review of his book by R.I. Page) published a book (and a follow up in 1994) questioning the methodology of its critics. He asserted that the odd philological problems in the Runestone could be the result of normal dialectic variances in Old Swedish during the purported carving of the Runestone. Further, he contended that critics had failed to consider the physical evidence, which he found leaning heavily in favour of authenticity. Meanwhile in The Vikings and America (1986) former UCLA professor Erik Wahlgren wrote that the text bore linguistic abnormalities and spellings that suggested the Runestone was a forgery.

[edit] Richard Nielsen

In 1983, inspired by Hall, Richard Nielsen, a trained engineer and amateur language researcher from Houston, Texas, studied the Kensington Runestone's runology and linguistics, disputing several earlier claims of forgery. For example, the rune which had been interpreted as standing for the letter J (and according to critics, invented by the forger) could be interpreted as a rare form of the L rune found only in a few 14th century manuscripts.[27]

In 2001, Nielsen published an article on the Scandinavian Studies website refuting claims the runes were Dalecarlian (a more modern form). He asserted that while some runes on the Kensington Runestone are similar to Dalecarlian runes, over half have no such connection, and are best explained by 14th-century usage. As indicated by the later discovery of the Larsson runerows (see below) he was half right.

[edit] Text (Nielsen interpretation)

With one slight variation from the Larsson runerows, using the letter þ (representing "th" as in "think" or "this") instead of d, the inscription on the face (from which a few words may be missing due to spalling, particularly at the lower left corner where the surface is calcite rather than greywacke) reads:

| “ |

8:göter:ok:22:norrmen:po: |

” |

Translation: Unlike the version in the infobox above, this is based on Richard Nielsen's 2001 translation of the text, which attempts specifically to put it into a medieval context, giving variant readings of some words:

8 Geats and 22 Norwegians on ?? acquisition expedition from Vinland far west. We had traps by 2 shelters one day's travel to the north from this stone. We were fishing one day. After we came home, found 10 men red with blood and dead. AVM (Ave Maria) Deliver from evils.

The lateral (or side) text reads:

| “ |

har:10:mans:we:hawet:at:se: |

” |

Translation:

(I) have 10 men at the inland sea to look after our ship 14 days travel from this wealth/property. Year [of our Lord] 1362

When the original text is transcribed to the Latin script, the message becomes quite easy to read for any modern Scandinavian. This fact is one of the main arguments against the authenticity of the stone. The language of the inscription bears much closer resemblance to 19th century than 14th century Swedish.[3]

The AVM is historically consistent since any Scandinavian explorers would have been Catholic at that time. Earlier transliterations interpreted skelar as skjar, meaning skerries (small, rocky islands) but Nielsen's research suggested this meaning was unlikely, and the Larsson runerows confirm his claim.

[edit] Opthagelsefarth: Nielsen and others

As an example of the linguistic discussion that has surrounded this text, the Swedish term opthagelse farth (journey of discovery), or updagelsfard as it often appears, is not known to have existed in Old Swedish, Danish or Norwegian, nor in Middle Dutch or Middle Low German during the 14th or 15th centuries. In the contemporary and modern Scandinavian languages it is called opdagelsesrejse in Danish, oppdagingsferd in Norwegian and upptäcktsfärd in Swedish, and it is considered as a standard etymological fact that the modern word is a loan-translation from Low German *updagen, Dutch opdagen and German aufdecken, which are in their turn loan-translations of French découvrir. In a conversation with Holand in 1911 the lexicographer of the Old Swedish Dictionary (Soderwall) noted that his work was limited mostly to surviving legal documents written in formal and stilted language and that the root word opdage must have been a borrowed Germanic term (i.e. Low German, Dutch or High German); which is also indicated by the -else ending, which characterizes a whole class of words that the Scandinavians borrowed from their Southern neighbors. However, it cannot have been borrowed from those parts, before they in their turn had borrowed it from the French language, which did not happen before the 16th century. Linguists, who, due to this and other similar facts, reject the Medieval origin of the KSR, consider this word to be a neologism and have noted that late 19th century Norwegian historian Gustav Storm often used the term in a series of articles on Viking exploration published in a Norwegian newspaper known to have been circulated in Minnesota.

Nielsen suggests that the Þ transliterated above as th or d could also be given a t sound, so for him the word translates as uptagelsfart (acquisition expedition), also an acceptable 14th-century expression. A problem with this suggestion is that in the rest of the text, the Thorn rune regularly corresponds to modern Scandinavian d-sounds and only occasionally to historical th-sounds while the T-rune is used for all other t-sounds.

[edit] More linguistic problems

Another characteristic pointed out by skeptics is the text's lack of cases. Norse had the four cases of modern German. They had disappeared from common speech by the 16th century but were still predominant in the 14th century (see Swedish language). Moreover the text does not use plural verb forms, that were common in the 14th century and have only recently disappeared from the modern languages. The examples are (plural forms in parenthesis) "wi war" (wörum), "hathe" (höfuðum), "[wi] fiske" (fiskaðum), "kom" (komum), "fann" (funnum) and "wi hathe" (hafdum). On the other hand, proponents of the stone's authenticity point to sporadic examples of these simpler forms already in some 14th-century texts—a century during the latter part of which great changes began to take place in the morphological system of the Scandinavian languages.

The inscription contains special runic numerals, known as "pentadic" numerals. Such numerals are known in Scandinavia, but nearly always from relatively recent times, not from verified medieval runic monuments, on which numbers were usually written as words with individual runes. For example, to write EINN (one) the runes E-I-N-N were used (not numerals) and indeed the word EN (one) is in the Kensington inscription. Writing all the numbers out (such as thirteen hundred and sixty-two) would have severely cramped the available surface space, so the stone's author (whether a forger or 14th-century explorer) simplified things by using these pentadic runes as numerals in the Indo-Arabic positional numbering system, which had been described in an early 14th century Icelandic book called Hauksbók, known to have been taken to Norway by its compiler Haukr Erlendsson. But the few pages of Hauksbók, called Algorismus, that describe the Indo-Arabic numerals and how to use them in calculations, were not known to very many at the time, and the Indo-Arabic number system did not become widespread in Scandinavia until centuries later.

[edit] AVM: A Medieval Abbreviation?

In 2004, Keith Massey and Kevin Massey published their theory that the Latin letters on the Kensington Stone, AVM, contain evidence authenticating a medieval date for the artifact. [28] The Kensington Stone critic Erik Wahlgren had noticed that the carver had incised a notch on the upper right hand corner of the letter V.[3] The Massey Twins note that a mark in that position is consistent with an abbreviation technique used in the 14th century. To render the word "Ave" in that period, the final vowel would have been written as a superscript. Eventually, the superscript vowel was replaced by a mere superscript dot. The existence of a notch where Wahlgren notes, then, shows that the carver was familiar with 14th century abbreviation techniques. The Massey Twins, however, point out that knowledge of these conventions was not available to the purported forger in late 19th century Minnesota, as books documenting these techniques were being printed in Italian academic circles only a few years after Öhman discovered the stone.

[edit] Rune statistics

The Kensington inscription consists of 30 different runic characters. Of these, 19 belong to the normal futhark series, q.e. a, b, d, e, f, g, h, i, k, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, th, and v. Then there are three special umlauted runes, that are marked by two dots above them. These represent the letters u, ä and ö. There is also a bind rune that represents the combination EL. Finally, there are seven others that represent the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 10. These results are obtained by counting how many times each rune recurs on the stone. Since the included photographs of the stone are quite sharp, the reader can easily verify this. Furthermore, it is also quite easy to see what Latin letter each rune represents, since most of the words are readily recognized as modern Swedish words. The result of such analysis also agrees nicely with the runic alphabets recorded by Edward Larsson in 1885.

[edit] Edward Larsson's notes

Many runes in the inscription deviate from known medieval runes, but in 2004 it was discovered that these appear along with pentadic runes in the 1883 notes of a 16-year-old journeyman tailor with an interest in folk music, Edward Larsson.[29] A copy was published by the Institute for Dialectology, Onomastics and Folklore Research in Umeå, Sweden and while an accompanying article suggested the runes were a secret cipher used by the tailors guild, no usage of futharks by any 19th-century guild has been documented. However, given that the Larsson notes are the only firm evidence for 19th century knowledge of these futharks, it does appear that a secret has been kept with considerable success. The notes also include the Pigpen cipher, devised by the Freemasons, and it may not be coincidental that the abbreviation AVM seen in Latin letters on the Kensington stone also appears (for AUM) on many Masonic gravestones; Wolter and Nielsen in their 2005 book even suggested a connection with the Knights Templar.

Larsson's notes disprove the early theory that the unusual runes on the KRS were invented on the spot by the supposed 1890s hoaxer; but without a source for Larsson's runerows (for example an ancient book, or records from the hypothetical Masonic-type organisation), it is not possible to give their origin any particular date range closer than "before 1883." However, his second runerow includes runes for the letters Å, Ä and Ö, which were introduced into the Swedish version of the Latin alphabet in the 16th century [30]. Although Nielsen has demonstrated that double-dotted runes were used in medieval inscriptions to indicate lengthened vowels, the presence of other letters from the second Larsson runerow on the Kensington stone suggests that the post-16th century versions were intended in this case.

[edit] The stone and the Larsson runes

Before Edward Larsson's sheet of runic alphabets surfaced in Sweden in 2004, one was very much in doubt which one of the many different Futharks that are historically known, was represented here.[clarification needed] Larsson's sheet lists two different Futharks. The first Futhark consists of 22 runes, the last two of which are bind-runes, representing the letter-combinations EL and MW. His second Futhark consists of 27 runes, where the last 3 are specially adapted to represent the letters å, ä, and ö of the modern Swedish alphabet.[29]

Comparing these three Futharks — the Kensington Futhark with Larsson's two — it becomes clear that the Kensington runes are largely a selective combination of Larsson's two Futharks: On the stone the runes representing e, g, n, and i have been taken from Larsson's first Futhark, and the runes representing the letters a, b, k, u, v, ä, and ö have been taken from Larsson's second Futhark. These clarifications arose after the stone had been taken to Sweden to be exhibited there.

[edit] Physical analysis

In December 1998, just over a hundred years after the Kensington Runestone had been found, a detailed physical analysis was made for the first time since Winchell's report in 1910. This included photography with a reflected light microscope, core sampling and examination with a scanning electron microscope.

In November 2000, geologist Scott F. Wolter presented preliminary findings suggesting the stone had undergone an in-the-ground weathering process that would have taken a minimum of 50–200 years. Specifically, he found a complete breakdown of mica crystals on the inscribed surface of the stone. [31] Samples from slate gravestones in Maine dating back 200 years showed considerable crystal degradation but not the complete breakdown seen on the runestone. What the comparison cannot tell is what conditions the Runestone endured after it was carved—for example, how long the inscription was exposed to the air before ending up face-down.

Recently[when?], an authentic rune was discovered in a 13th century document that was identical to one of the unusual runes on the Runestone, which linguistic experts had suggested was invented by a hoaxer.[citation needed] In response, Wolter examined each individual rune on the Kensington stone with a microscope. He found a series of dots engraved inside four R-shaped runes. Research found that identical dotted runes are found only on 14th century graves in churches on the island of Gotland off the coast of Sweden. Wolter considered this proof of the runestone's authenticity.

Some critics have noted the surviving sharpness of the chisel work, asking how this could have endured centuries of freeze-thaw cycles and seepage. However, the back of the stone has crisply preserved glacial scratches that are thousands of years old. Other observers contend the runes have weathered consistently with the rest of the stone.

[edit] Conclusion

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

The consensus among runologists and linguists (such as R. I. Page and James Knirk) is that the runestone is a hoax, while many enthusiasts claim scientific evidence points to its authenticity.

The Kensington Runestone could be a 19th century forgery or an important archaeological find from the 14th century. Those who ascribe a Scandinavian origin to the stone claim it shows evidence of obscure medieval runes and intersecting word forms that would have been unknown to potential forgers in the 1800s. These advocates tend to be enthusiastic but often lacking in professional credentials (Viking-origin proponent Keith Massey holds a Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where Erik Wahlgren taught). Interested professional archaeologists, historians, and Scandinavian linguists generally question the stone's provenance. Any discussion of the runestone is fraught with opportunities for misinterpretation and speculation.

The amateur linguist Nielsen claims the stone's linguistics are plausible for the 14th century, claiming evidence for all the unusual word and rune forms has been found in medieval sources. He believes that spoken Swedish was already quite similar to modern Swedish in the 14th century, But his only evidence for this is the Kensington Stones. The many other [written] sources of Medieval Swedish show a language that differs in significant ways from its modern descendant. Geochemical analysis suggests the stone was buried prior to the first documented arrival of Europeans in the region.

In a joint statement for a 2004 exhibition of the stone at the Museum of National Antiquities in Stockholm, Nielsen and Henrik Williams (a professor of Scandinavian Languages at Uppsala University and a proponent of the forgery theory) noted there were linguistic discrepancies for both 14th and 19th century origins of the inscription and that the runestone "requires further study before a secure conclusion can be reached." This was a rare instance in which the academic community and runestone enthusiasts found something upon which they could agree.

[edit] See also

- L'Anse aux Meadows

- Nomans Land (Massachusetts)

- Bat Creek Inscription

- Heavener Runestone

- Turkey Mountain inscriptions

- Shawnee Runestone

- Poteau Runestone

- Viking Altar Rock

- Vinland map

- Bryggen inscriptions

- Kingigtorssuaq Runestone

- Spirit Pond runestones

[edit] References

- ^ Owen, Francis (1990). The Germanic people: their origin, expansion, and culture. New York: Dorset Press. ISBN 0-88029-579-1.

- ^ "forskning.no Kan du stole pÃ¥ Wikipedia?" (in Norwegian). http://www.forskning.no/Artikler/2005/desember/1133429879.66. Retrieved on 2008-12-19. "Det finnes en liten klikk med amerikanere som sverger til at steinen er ekte. De er stort sett skandinaviskættede realister uten peiling på språk, og de har store skarer med tilhengere." Translation: "There is a small clic of Americans who swear to the stone's authenticity. They are mainly natural scientists of Scandinavian descent with no knowledge of linguistics, and they have large numbers of adherents."

- ^ a b c d Wahlgren, Erik (1958). The Kensington Stone, A Mystery Solved. University of Wisconsin Press.

- ^ a b Blegen, T (1960). 0873510445. Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0873510445.

- ^ a b Fridley, R (1976). "The case of the Gran tapes". Minnesota History 45 (4): 152-156.

- ^ Wallace, B (1971). "Some points of controversy". in Ashe G et al.. The Quest for America. New York: Praeger. pp. 154-174. ISBN 0269027874.

- ^ Wahlgren, Erik (1986) (in Wahlgren1986). The Vikings and America (Ancient Peoples and Places). Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500021090.

- ^ a b Michlovic MG (1990). "Folk Archaeology in Anthropological Perspective". Current Anthropology 31 (11): 103-107.

- ^ Hughey M, Michlovic MG (1989). "Making history: The Vikings in the American heartland". Politics, Culture and Society 2: 338-360.

- ^ Extract from 1886 plat map of Solem township, http://www.geocities.com/thetropics/island/3634/platt.html, retrieved on 2007-10-31

- ^ "Done in Runes", Minneapolis Journal (appendix to "The Kensington Rune Stone" by T. Blegen, 1968), 22 February 1899, http://books.google.com/books?id=DU2LbIbBK7oC&dq=kensington+runestone+%22van+dyke%22&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=7SDn4zvxNE&sig=vclglKN-pZ1-Aw6zSHo0rSWZg9g#PPA129,M1, retrieved on 2007-11-28

- ^ Michael G. Michlovic, "Folk Archaeology in Anthropological Perspective" Current Anthropology 31.1 (February 1990:103-107) p. 105ff.

- ^ Holand, "First authoritative investigation of oldest document in America", Journal of American History 3 (1910:165-84); Michlovic noted Holand's contrast of the Scandinavians as undaunted, brave, daring, faithful and intrepid contrasted with the Indians, as savages, wild heathens, pillagers, vengeful, like wild beasts, an interpretation that "placed it squarely within the framework of Indian-white relations in Minnesota at the time of its discovery." (Michlovic 1990:106).

- ^ a b Winchell NH, Flom G (1910). "The Kensington Rune Stone: Preliminary Report". Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society 15. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2000.03.0048;query=toc;layout=;loc=224. Retrieved on 2007-11-28.

- ^ Milo M. Quaife, "The myth of the Kensington runestone: The Norse discovery of Minnesota 1362" in The New England Quarterly December 1934

- ^ Lobeck, Engebret P. (1867), Holmes City narrative on Trysil (Norway) emigrants website, http://www.digitalheadhouse.com/family/reunion/History.htm, retrieved on 2007-10-31

- ^ "Kensington Runestone Museum, Alexandria Minnesota". http://www.runestonemuseum.org. Retrieved on 2008-12-19.

- ^ a b Taylor, E.G.R. (1956), "A Letter Dated 1577 from Mercator to John Dee", Imago Mundi 13: 56–68, doi:

- ^ Full text in Diplomatarium Norvegicum English translation

- ^ Holand, Hjalmar (1959), "An English scientist in America 130 years before Columbus", Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy 48: 205–219ff, http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/WI/WI-idx?type=article&did=WI.WT1959.HRHOLAND&isize=M&q1=wisconsin%20academy

- ^ Flom, George T. "The Kensington Rune-Stone" Springfield IL, Illinois State Historical Soc. (1910) p37

- ^ Pohl, Frederick J. "Atlantic Crossings before Columbus" New York, W.W. Norton & Co. (1961) p212

- ^ Powell, Bernard W. (1958), "The Mooring Hole Problem in Long Island Sound", Bulletin of the Massachusetts Archaeological Society 19(2): 31, http://www.bwpowell.com/archeology/thevikings/mooring.html

- ^ Holand, Hjalmar (1937), "The Climax Fire Steel", Minnesota History 18: 188–190

- ^ Kalm, Pehr (1748), Travels into North America (vol. 2, pages 279-81), http://content.wisconsinhistory.org/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/aj&CISOPTR=16932&CISOSHOW=16777&REC=1, retrieved on 2007-11-05

- ^ "Olof Ohman's Runes". TIME. 8 Oct. 1951. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,859375,00.html. Retrieved on 2009-02-08.

- ^ The Kensington Runestone - sk(l)ar

- ^ Keith and Kevin Massey, “Authentic Medieval Elements in the Kensington Stone" in Epigraphic Society Occasional Publications Vol. 24 2004, pp 176-182

- ^ a b Tryggve Sköld (2003). "Edward Larssons alfabet och Kensingtonstenens" (in (Swedish)) (PDF). DAUM-katta (Umeå: Dialekt-, ortnamns- och folkminnesarkivet i Umeå) (Winter 2003): 7–11. ISSN 1401-548X. http://www2.sofi.se/daum/katta/katta13/katta13.pdf. Retrieved on 06-02-2009.

- ^ unilang.org on the Swedish alphabet

- ^ Wolter, Scott; Veglahn, Sherry (Winter 2001), "Runestone Examined: Real or Hoax?", American Engineering Testing Inc. Newsletter (Internet Archive), http://web.archive.org/web/20020818213903/http://www.amengtest.com/news/01winter/runestone.html, retrieved on 2007-11-28

[edit] Literature

- Thalbitzer, William C. (1951). Two runic stones, from Greenland and Minnesota. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 2585531.

[edit] External links

- "Kensingtonstenens gåta - The riddle of the Kensington runestone" (in (Swedish) and (English)) (PDF). Historiska nyheter (Stockholm: Statens historiska museum) (Specialnummer om Kensingtonstenen): 16 pages. 2003. ISSN 0280-4115. http://www.kensingtonrunestone.com/HN_kensington.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-12-19.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck (2005). The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically. Waveland Press. ISBN 1577663713.

- "Kensington Runestone Museum, Alexandria Minnesota". http://www.runestonemuseum.org. Retrieved on 2008-12-19.

- Kensington Rune Stone story (KBJR-TV, Duluth, Minnesota)