Supraventricular tachycardia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2008) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia Classification and external resources |

|

| ICD-10 | I47.1 |

|---|---|

| ICD-9 | 427.89 |

| MeSH | D013617 |

A supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) also known as Paroxysmal SupraVentricular Tachycardia (PSVT) is a rapid rhythm of the heart in which the origin of the electrical signal is either the atria or the AV node. This is in contrast to the deadlier ventricular tachycardias, which are rapid rhythms that originate from the ventricles of the heart, that is, below the atria or AV node.

Contents |

[edit] Symptoms

Symptoms can come on suddenly and may go away without treatment. They can last a few minutes or as long as 1-2 days. The rapid beating of the heart during SVT can make the heart a less effective pump so that the cardiac output is decreased and the blood pressure drops. The following symptoms are typical with a rapid pulse of 150-250 beats per minute:

- Pounding chest

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Rapid breathing

- Dizziness

- Loss of consciousness (in serious cases)

- Numbness of various body parts

[edit] Terminology

The term supraventricular tachycardia is often used differently in different settings.

- Properly, it refers to any tachycardia that is not ventricular in origin. This definition includes sinus tachycardia. Supraventricular tachycardia can be divided into atrial tachycardia and junctional tachycardia.[1]

- Often, however, in a clinical setting, it is used loosely as a synonym for paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT). This term refers to those SVTs that have a sudden, almost immediate onset.[2] A person experiencing PSVT may see their heart rate go from 90 to 180 beats per minute instantaneously. Because sinus tachycardias (and some other SVTs) have a gradual (i.e. non-immediate) onset, they are excluded from the PSVT category. PSVTs are usually AV nodal reentrant tachycardias.

[edit] Types

The following are types of supraventricular tachycardias, each with a different mechanism of impulse maintenance:

SVTs from a sinoatrial source:

SVTs from an atrial source:

- (Unifocal) Atrial tachycardia (AT)

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT)

- Atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response

- Atrial flutter with a rapid ventricular response

SVTs from an atrioventricular source:

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT)

- AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT)

- Junctional ectopic tachycardia

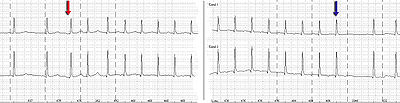

[edit] Diagnosis

Most supraventricular tachycardias have a narrow QRS complex on ECG, but it is important to realise that supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction (SVTAC) can produce a wide-complex tachycardia that may mimic ventricular tachycardia (VT). In the clinical setting, it is important to determine whether a wide-complex tachycardia is an SVT or a ventricular tachycardia, since they are treated differently. Ventricular tachycardia has to be treated appropriately, since it can quickly degenerate to ventricular fibrillation and death. A number of different algorithms have been devised to determine whether a wide complex tachycardia is supraventricular or ventricular in origin.[3] In general, a history of structural heart disease dramatically increases the likelihood that the tachycardia is ventricular in origin.

The individual subtypes of SVT can be distinguished from each other by certain physiological and electrical characteristics, many of which present in the patient's ECG.

- Sinus tachycardia is considered "appropriate" when a reasonable stimulus, such as the catecholamine surge associated with fright, stress, or physical activity, provokes the tachycardia. It is distinguished by a presentation identical to a normal sinus rhythm except for its fast rate (>100 beats per minute in adults).

- Sinoatrial node reentrant tachycardia (SANRT) is caused by a reentry circuit localised to the SA node, resulting in a normal-morphology p-wave that falls before a regular, narrow QRS complex. It is therefore impossible to distinguish on the ECG from ordinary sinus tachycardia. It may however be distinguished by its prompt response to vagal manoeuvres.

- (Unifocal) Atrial tachycardia is tachycardia resultant from one ectopic focus within the atria, distinguished by a consistent p-wave of abnormal morphology that fall before a narrow, regular QRS complex.

- Multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT) is tachycardia resultant from at least three ectopic foci within the atria, distinguished by p-waves of at least three different morphologies that all fall before irregular, narrow QRS complexes.

- Atrial fibrillation is not, in itself, a tachycardia, but when it is associated with a rapid ventricular response greater than 100 beats per minute, it becomes a tachycardia. A-fib is characteristically an "irregularly irregular rhythm" both in its atrial and ventricular depolarizations. It is distinguished by fibrillatory p-waves that, at some point in their chaos, stimulate a response from the ventricles in the form of irregular, narrow QRS complexes.

- Atrial flutter, is caused by a re-entry rhythm in the atria, with a regular rate of about 300 beats per minute. On the ECG, this appears as a line of "sawtooth" p-waves. The AV node will not usually conduct such a fast rate, and so the P:QRS usually involves a 2:1 or 4:1 block pattern, (though rarely 3:1, and sometimes 1:1 in setting of class IC anti-arrhythmic drug use). Because the ratio of P to QRS is usually consistent, A-flutter is often regular in comparison to its irregular counterpart, A-fib. Atrial Flutter is also not necessarily a tachycardia unless the AV node permits a ventricular response greater than 100 beats per minute.

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT) is also sometimes referred to as a junctional reciprocating tachycardia. It involves a reentry circuit forming just next to or within the AV node itself. The circuit most often involves two tiny pathways one faster than the other, within the AV node. Because the AV node is immediately between the atria and the ventricle, the re-entry circuit often stimulates both, meaning that a retrogradely conducted p-wave is buried within or occurs just after the regular, narrow QRS complexes.

- Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia (AVRT), also known as circus movement tachycardia (CMT), also results from a reentry circuit, although one physically much larger than AVNRT. One portion of the circuit is usually the AV node, and the other, an abnormal accessory pathway from the atria to the ventricle. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a relatively common abnormality with an accessory pathway, the Bundle of Kent crossing the A-V valvular ring.

- In orthodromic AVRT, atrial impulses are conducted down through the AV node and retrogradely re-enter the atrium via the accessory pathway. A distinguishing characteristic of orthodromic AVRT can therefore be a p-wave that follows each of its regular, narrow QRS complexes, due to retrograde conduction.

- In antidromic AVRT, atrial impulses are conducted down through the accessory pathway and re-enter the atrium retrogradely via the AV node. Because the accessory pathway initiates conduction in the ventricles outside of the bundle of His, the QRS complex in antidromic AVRT is often wider than usual, with a delta wave.

- Finally, Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia or JET is a rare tachycardia caused by increased automaticity of the AV node itself initiating frequent heart beats. On the ECG, junctional tachycardia often presents with abnormal morphology p-waves that may fall anywhere in relation to a regular, narrow QRS complex.

[edit] Acute Treatment

In general, SVT is not life threatening, but episodes should be treated or prevented. While some treatment modalities can be applied to all SVTs with impunity, there are specific therapies available to cure some of the different sub-types. Cure requires intimate knowledge of how and where the arrhythmia is initiated and propagated.

The SVTs can be separated into two groups, based on whether they involve the AV node for impulse maintenance or not. Those that involve the AV node can be terminated by slowing conduction through the AV node. Those that do not involve the AV node will not usually be stopped by AV nodal blocking manoevres. These manoevres are still useful however, as transient AV block will often unmask the underlying rhythm abnormality.

AV nodal blocking can be achieved in at least three different ways:

[edit] Physical Maneuver

A number of physical maneuvers cause increased AV nodal block, principally through activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, conducted to the heart by the vagus nerve. These manipulations are therefore collectively referred to as vagal maneuvers.

The valsalva maneuver should be the first vagal maneuver tried.[4] It works by increasing intra-thoracic pressure and affecting baro-receptors (pressure sensors) within the arch of the aorta. It is carried out by asking the patient to hold their breath and "bear down" as if straining to pass a bowel motion, or by getting them to hold their nose and blow out against it.[5]

There are many other vagal maneuvers including: holding ones breath for a few seconds, coughing, plunging the face into cold water,[5](via the diving reflex[6]), drinking a glass of ice cold water, and standing on one's head. Carotid sinus massage, carried out by firmly pressing the bulb at the top of one of the carotid arteries in the neck, is effective but is often not recommended due to risks of stroke in those with plaque in the carotid arteries.

If necessary, the act of defaecation can sometimes halt an episode, again through vagal stimuation.

[edit] Drug Treatment

Another modality involves treatment with medications. Adenosine, an ultra short acting AV nodal blocking agent, is indicated if vagal maneuvers are not effective [1].[7] If this works, followup therapy with diltiazem, verapamil or metoprolol may be indicated. SVT that does NOT involve the AV node may respond to other anti-arrhythmic drugs such as sotalol or amiodarone.

In pregnancy, metoprolol is the treatment of choice as recommended by the American Heart Association.

[edit] Electrical Cardioversion

If the patient is unstable or other treatments have not been effective, cardioversion may be used, and is almost always effective.

[edit] Prevention & Cure

Once the acute episode has been terminated, ongoing treatment may be indicated to prevent a recurrence of the arrhythmia. Patients who have a single isolated episode, or infrequent and minimally symptomatic episodes usually do not warrant any treatment except observation.

Patients who have more frequent or disabling symptoms from their episodes generally warrant some form of preventative therapy. A variety of drugs including simple AV nodal blocking agents like beta-blockers and verapamil, as well as anti-arrhythmics may be used, usually with good effect, although the risks of these therapies need to be weighed against the potential benefits.

For tachycardia caused by a re-entrant pathway, radio frequency ablation is probably the best option. This is a low risk procedure that uses a catheter inside the heart to deliver radio frequency energy to locate and destroy the abnormal electrical pathways. Ablation has been shown to be highly effective: up to 99% effective in eliminating AVNRT. Similar high rates of success are achieved with radio frequency ablation in eliminating AVRT and typical Atrial Flutter.

There is a much newer treatment for SVT involving the AV node directly. This treatment is called Cryoablation. SVT involving the AV node is often a contraindication for using radiofrequency ablation due to the high incidence of injuring the AV node requiring a permanent pacemaker. With Cryoablation, a supercooled catheter is used (cooled by nitrous oxide gas), and the tissue is frozen to - 10 C. This provides the same result as radiofrequency ablation but does not carry the same risk. If you freeze the tissue and then realize you are in a dangerous spot, you can halt freezing the tissue and allow the tissue to spontaneously rewarm and the tissue is the same as if you never touched it. If after freezing the tissue to - 10 C, you get the desired result, then you freeze the tissue down to a temperature of - 73 C and you permanently ablate the tissue.

This therapy has revolutionized AVNRT and other AV nodal tachyarrythmias. It has allowed people who were otherwise not a candidate for radiofrequency ablation to have a chance at having their problem cured. This technology was pioneered at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, Ohio by Dr. Mark Krebs, Matthew Hoskins RN, BSN, and Ken Peterman RN, BSN. in 2004.

[edit] Notable cases

After being successfully diagnosed and treated, Bobby Julich went on to place third in the 1998 Tour de France and win a Bronze Medal in the 2004 Summer Olympics.[8] Women's Olympic volleyball player Tayyiba Haneef-Park underwent an ablation for SVT just two months before competing in the 2008 Summer Olympics.[9] Tony Blair, former PM of the UK, was also operated on for SVT. Anastacia was recently diagnosed with the disease (News of the World interview). Women's Olympic gold medalist swimmer, Rebecca Soni has had SVT and has had heart surgery for it. Miley Cyrus also has also been digonosed with it, as said in her book Miles To Go.

[edit] See also

- Tachycardia

- AV nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT)

- AV reentrant tachycardia (AVRT)

- Inappropriate Sinus Tachycardia

- Ashman phenomenon

[edit] References

- ^ supraventricular tachycardia at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Lau EW, Ng GA (2002). "Comparison of the performance of three diagnostic algorithms for regular broad complex tachycardia in practical application". Pacing and clinical electrophysiology : PACE 25 (5): 822–7. doi:. PMID 12049375.

- ^ "BestBets: Comparing Valsalva manoeuvre with carotid sinus massage in adults with supraventricular tachycardia". http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=930.

- ^ a b Vibhuti N, Singh; Monika Gugneja (2005-08-22). "Supraventricular Tachycardia". eMedicineHealth.com. http://www.emedicinehealth.com/supraventricular_tachycardia/page7_em.htm. Retrieved on 2008-11-28.

- ^ Mathew PK (January 1981). "Diving reflex. Another method of treating paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia". Arch. Intern. Med. 141 (1): 22–3. doi:. PMID 7447580.

- ^ "Adenosine vs Verapamil in the acute treatment of supraventricular tachycardias". http://www.bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=996.

- ^ An athlete's experience with Re-entrant Supraventricular Tachycardia

- ^ USA Volleyball 2008 Olympic Games Press Kit

[edit] External links

- Supraventricular Tachycardia information from Seattle Children's Hospital Heart Center

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||