p53

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| edit |

p53 (also known as protein 53 or tumor protein 53), is a transcription factor which in humans is encoded by the TP53 gene.[1][2][3] p53 is important in multicellular organisms, where it regulates the cell cycle and thus functions as a tumor suppressor that is involved in preventing cancer. As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the genome," "the guardian angel gene," and the "master watchman," referring to its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation.[4]

The name p53 is in reference to its apparent molecular mass: it runs as a 53 kilodalton (kDa) protein on SDS-PAGE. But based on calculations from its amino acid residues, p53's mass is actually only 43.7kDa. This difference is due to the high number of proline residues in the protein which slow its migration on SDS-PAGE, thus making it appear larger than it actually is[5]. This effect is observed with p53 from a variety of species, including humans, rodents, frogs and fish.

Contents |

[edit] Gene

In humans, p53 is encoded by the TP53 gene (guardian of the cell) located on the short arm of chromosome 17 (17p13.1).[1][2][3]

The gene is on different locations in other animals:

(Italics are used to distinguish the TP53 gene name from the protein it encodes.)

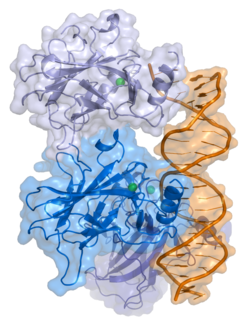

[edit] Structure

Human p53 is 393 amino acids long and has seven domains:

- N-terminal transcription-activation domain (TAD), also known as activation domain 1 (AD1) which activates transcription factors: residues 1-42.

- activation domain 2 (AD2) important for apoptotic activity: residues 43-63.

- Proline rich domain important for the apoptotic activity of p53: residues 80-94.

- central DNA-binding core domain (DBD). Contains one zinc atom and several arginine amino acids: residues 100-300.

- nuclear localization signalling domain, residues 316-325.

- homo-oligomerisation domain (OD): residues 307-355. Tetramerization is essential for the activity of p53 in vivo.

- C-terminal involved in downregulation of DNA binding of the central domain: residues 356-393.[6]

A tandem of nine-amino-acid transactivation domains (9aaTAD) was identified in the AD1 and AD2 regions of transcription factor p53.[7] KO mutations and position for p53 interaction with TFIID are listed below:[8]

| description | position | sequence |

|---|---|---|

| 9aaTAD I | amino acids 17-25 | E TFSD LWKL |

| TAF9 interaction | amino acids 19-23 | FSD LW |

| KO mutant L22Q/W23S of 9aaTAD I | amino acids 17-25 | E TFSD QSKL |

| 9aaTAD II | amino acids 48-56 | D DIEQ WFTE |

| KO mutant W53Q/F54S of 9aaTAD II | amino acids 48-56 | D DIEQ QSTE |

Mutations that deactivate p53 in cancer usually occur in the DBD. Most of these mutations destroy the ability of the protein to bind to its target DNA sequences, and thus prevents transcriptional activation of these genes. As such, mutations in the DBD are recessive loss-of-function mutations. Molecules of p53 with mutations in the OD dimerise with wild-type p53, and prevent them from activating transcription. Therefore OD mutations have a dominant negative effect on the function of p53.

Wild-type p53 is a labile protein, comprising folded and unstructured regions which function in a synergistic manner.[9]

[edit] Functional significance

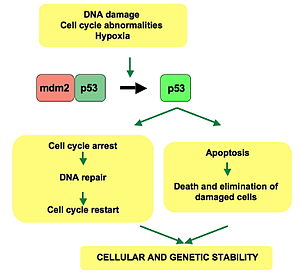

p53 has many anti-cancer mechanisms:

- It can activate DNA repair proteins when DNA has sustained damage.

- It can also hold the cell cycle at the G1/S regulation point on DNA damage recognition (if it holds the cell here for long enough, the DNA repair proteins will have time to fix the damage and the cell will be allowed to continue the cell cycle.)

- It can initiate apoptosis, the programmed cell death, if the DNA damage proves to be irreparable.

p53 is central to many of the cell's anti-cancer mechanisms. It can induce growth arrest, apoptosis and cell senescence. In normal cells p53 is usually inactive, bound to the protein MDM2 (also called HDM2 in humans), which prevents its action and promotes its degradation by acting as ubiquitin ligase. Active p53 is induced after the effects of various cancer-causing agents such as UV radiation, oncogenes and some DNA-damaging drugs. DNA damage is sensed by 'checkpoints' in a cell's cycle, and causes proteins such as ATM, CHK1 and CHK2 to phosphorylate p53 at sites that are close to or within the MDM2-binding region and p300-binding region of the protein. Oncogenes also stimulate p53 activation, mediated by the protein p14ARF. Some oncogenes can also stimulate the transcription of proteins which bind to MDM2 and inhibit its activity. Once activated p53 activates expression of several genes including one encoding for p21. p21 binds to the G1-S/CDK and S/CDK complexes (molecules important for the G1/S transition in the cell cycle) inhibiting their activity. p53 has many anticancer mechanisms, and plays a role in apoptosis, genetic stability, and inhibition of angiogenesis.

The p53 gene has been mapped to chromosome 17. In the cell, p53 protein binds DNA, which in turn stimulates another gene to produce a protein called p21 that interacts with a cell division-stimulating protein (cdk2). When p21 is complexed with cdk2 the cell cannot pass through to the next stage of cell division. Mutant p53 can no longer bind DNA in an effective way, and as a consequence the p21 protein is not made available to act as the 'stop signal' for cell division. Thus cells divide uncontrollably, and form tumors.[10]

Recent research has also linked the p53 and RB1 pathways, via p14ARF, raising the possibility that the pathways may regulate each other.[11]

Research published in 2007 showed when p53 expression is stimulated by sunlight, it begins the chain of events leading to tanning.[12][13]

[edit] Regulation of p53 activity

p53 becomes activated in response to a myriad of stress types, which include but is not limited to DNA damage (induced by either UV, IR or chemical agents,such as hydrogen peroxide), oxidative stress,[14] osmotic shock, ribonucleotide depletion and deregulated oncogene expression. This activation is marked by two major events. Firstly, the half-life of the p53 protein is increased drastically, leading to a quick accumulation of p53 in stressed cells. Secondly, a conformational change forces p53 to take on an active role as a transcription regulator in these cells. The critical event leading to the activation of p53 is the phosphorylation of its N-terminal domain. The N-terminal transcriptional activation domain contains a large number of phosphorylation sites and can be considered as the primary target for protein kinases transducing stress signals.

The protein kinases that are known to target this transcriptional activation domain of p53 can be roughly divided into two groups. A first group of protein kinases belongs to the MAPK family (JNK1-3, ERK1-2, p38 MAPK), which is known to respond to several types of stress, such as membrane damage, oxidative stress, osmotic shock, heat shock, etc... A second group of protein kinases (ATR, ATM, Chk1, Chk2, DNA-PK, CAK) is implicated in the genome integrity checkpoint, a molecular cascade that detects and responds to several forms of DNA damage caused by genotoxic stress.

In unstressed cells, p53 levels are kept low through a continuous degradation of p53. A protein called Mdm2 binds to p53 and transports it from the nucleus to the cytosol where it becomes degraded by the proteasome. Phosphorylation of the N-terminal end of p53 by the above-mentioned protein kinases disrupts Mdm2-binding. Other proteins, such as Pin1, are then recruited to p53 and induce a conformational change in p53 which prevents Mdm2-binding even more. Trancriptional coactivators, like p300 or PCAF, then acetylate the carboxy-terminal end of p53, exposing the DNA binding domain of p53, allowing it to activate or repress specific genes. Deacetylase enzymes, such as Sirt1 and Sirt7, can deacetylate p53, leading to an inhibition of apoptosis.[15]

[edit] Role in disease

If the TP53 gene is damaged, tumor suppression is severely reduced. People who inherit only one functional copy of the TP53 gene will most likely develop tumors in early adulthood, a disease known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome. The TP53 gene can also be damaged in cells by mutagens (chemicals, radiation or viruses), increasing the likelihood that the cell will begin uncontrolled division. More than 50 percent of human tumors contain a mutation or deletion of the TP53 gene. Increasing the amount of p53, which may initially seem a good way to treat tumors or prevent them from spreading, is in actuality not a usable method of treatment, since it can cause premature aging.[16] However, restoring endogenous p53 function holds a lot of promise.[17]

Certain pathogens can also affect the p53 protein that the TP53 gene expresses. One such example, the Human papillomavirus (HPV), encodes a protein, E6, which binds the p53 protein and inactivates it. This, in synergy with the inactivation of another cell cycle regulator, p105RB, allows for repeated cell division manifestested in the clinical disease of warts. Infection by oncogenic HPV types, especially HPV16, can also lead to progression from a benign wart to low or high-grade cervical dysplasia which are reversible forms of precancerous lesions. Persistent infection over the years causes irreversible changes leading to Carcinoma in situ and eventually invasive cervical cancer. This results from the effects of HPV genes, particularly those encoding E6 and E7, which are the two viral oncoproteins that are preferentially retained and expressed in cervical cancers by integration of the viral DNA into the host genome.[18]

In healthy humans, the p53 protein is continually produced and degraded in the cell. The degradation of the p53 protein is, as mentioned, associated with MDM2 binding. In a negative feedback loop MDM2 is itself induced by the p53 protein. However mutant p53 proteins often don't induce MDM2, and are thus able to accumulate at very high concentrations. Worse, mutant p53 protein itself can inhibit normal p53 protein levels.

[edit] History

p53 was identified in 1979 by Lionel Crawford, David Lane (Oncology), Arnold Levine, and Lloyd Old, working at Imperial Cancer Research Fund (UK) Princeton University, and Sloan-Kettering Memorial Hospital, respectively. It had been hypothesized to exist before as the target of the SV40 virus, a strain that induced development of tumors. The TP53 gene from the mouse was first cloned by Peter Chumakov of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1982,[19] and independently in 1983 by Moshe Oren (Weizmann Institute).[20] The human TP53 gene was cloned in 1984.[1]

It was initially presumed to be an oncogene due to the use of mutated cDNA following purification of tumour cell mRNA. Its character as a tumor suppressor gene was finally revealed in 1989 by Bert Vogelstein working at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine.[21]

Warren Maltzman, of the Waksman Institute of Rutgers University first demonstrated that TP53 was responsive to DNA damage in the form of ultraviolet radiation.[22] In a series of publications in 1991-92, Michael Kastan, Johns Hopkins University, reported that TP53 was a critical part of a signal transduction pathway that helped cells respond to DNA damage.[23]

In 1993, p53 was voted molecule of the year by Science magazine.[24]

[edit] Other names

- Official protein name: Cellular tumor antigen p53

- Tumor suppressor p53

- Transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53)

- Phosphoprotein p53

- Antigen NY-CO-13

[edit] References

- ^ a b c Matlashewski G, Lamb P, Pim D, Peacock J, Crawford L, Benchimol S (December 1984). "Isolation and characterization of a human p53 cDNA clone: expression of the human p53 gene". EMBO J. 3 (13): 3257–62. PMID 6396087.

- ^ a b Isobe M, Emanuel BS, Givol D, Oren M, Croce CM (1986). "Localization of gene for human p53 tumour antigen to band 17p13". Nature 320 (6057): 84–5. doi:. PMID 3456488.

- ^ a b Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Bruskin A, Jarosz D, Friedman P, Prives C, Vogelstein B (June 1991). "Identification of p53 as a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein". Science (journal) 252 (5013): 1708–11. PMID 2047879. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=2047879.

- ^ Read, A. P.; Strachan, T. (1999). "Chapter 18: Cancer Genetics". Human molecular genetics 2. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-33061-2.

- ^ Ziemer MA, Mason A, Carlson DM (September 1982). "Cell-free translations of proline-rich protein mRNAs". J. Biol. Chem. 257 (18): 11176–80. PMID 7107651. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7107651.

- ^ Harms KL, Chen X (2005). "The C terminus of p53 family proteins is a cell fate determinant". Mol. Cell. Biol. 25 (5): 2014–30. doi:. PMID 15713654.

- ^ Piskacek S, Gregor M, Nemethova M, Grabner M, Kovarik P, Piskacek M (June 2007). "Nine-amino-acid transactivation domain: establishment and prediction utilities". Genomics 89 (6): 756–68. doi:. PMID 17467953.

- ^ Uesugi M, Nyanguile O, Lu H, Levine AJ, Verdine GL (August 1997). "Induced alpha helix in the VP16 activation domain upon binding to a human TAF". Science (journal) 277 (5330): 1310–3. doi:. PMID 9271577.Uesugi M, Verdine GL (December 1999). "The alpha-helical FXXPhiPhi motif in p53: TAF interaction and discrimination by MDM2". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (26): 14801–6. PMID 10611293. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10611293.Choi Y, Asada S, Uesugi M (May 2000). "Divergent hTAFII31-binding motifs hidden in activation domains". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (21): 15912–6. PMID 10821850. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10821850.Venot C, Maratrat M, Sierra V, Conseiller E, Debussche L (April 1999). "Definition of a p53 transactivation function-deficient mutant and characterization of two independent p53 transactivation subdomains". Oncogene 18 (14): 2405–10. PMID 10327062.Lin J, Chen J, Elenbaas B, Levine AJ (May 1994). "Several hydrophobic amino acids in the p53 amino-terminal domain are required for transcriptional activation, binding to mdm-2 and the adenovirus 5 E1B 55-kD protein". Genes Dev. 8 (10): 1235–46. PMID 7926727. http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7926727.

- ^ Bell S, Klein C, Müller L, Hansen S, Buchner J (2002). "p53 contains large unstructured regions in its native state". J. Mol. Biol. 322 (5): 917–27. doi:. PMID 12367518.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information. "The p53 tumor suppressor protein". Genes and Disease. United States National Institutes of Health. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?call=bv.View..ShowSection&rid=gnd.section.107. Retrieved on 2008-05-28.

- ^ Bates S, Phillips AC, Clark PA, Stott F, Peters G, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH (1998). "p14ARF links the tumour suppressors RB and p53". Nature 395 (6698): 124–5. doi:. PMID 9744267.

- ^ "Genome's guardian gets a tan started". New Scientist. March 17, 2007. http://www.newscientist.com/channel/health/mg19325955.800-genomes-guardian-gets-a-tan-started.html. Retrieved on 2007-03-29.

- ^ Cui R, Widlund HR, Feige E, Lin JY, Wilensky DL, Igras VE, D'Orazio J, Fung CY, Schanbacher CF, Granter SR, Fisher DE (2007). "Central role of p53 in the suntan response and pathologic hyperpigmentation". Cell 128 (5): 853–64. doi:. PMID 17350573.

- ^ Han ES, Muller FL, Pérez VI, Qi W, Liang H, Xi L, Fu C, Doyle E, Hickey M, Cornell J, Epstein CJ, Roberts LJ, Van Remmen H, Richardson A (June 2008). "The in vivo gene expression signature of oxidative stress". Physiol. Genomics 34 (1): 112–26. doi:. PMID 18445702.

- ^ Vakhrusheva O, Smolka C, Gajawada P, Kostin S, Boettger T, Kubin T, Braun T, Bober (March 2008). "Sirt7 increases stress resistance of cardiomyocytes and prevents apoptosis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy in mice". Circ. Res. 102 (6): 703–10. doi:. PMID 18239138.

- ^ Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, Lu X, Soron G, Cooper B, Brayton C, Hee Park S, Thompson T, Karsenty G, Bradley A, Donehower LA (2002). "p53 mutant mice that display early ageing-associated phenotypes". Nature 415 (6867): 45–53. doi:. PMID 11780111.

- ^ Ventura A, Kirsch DG, McLaughlin ME, Tuveson DA, Grimm J, Lintault L, Newman J, Reczek EE, Weissleder R, Jacks T (2007). "Restoration of p53 function leads to tumour regression in vivo". Nature 445 (7128): 661–5. doi:. PMID 17251932.

- ^ Angeletti PC, Zhang L, Wood C (2008). "The viral etiology of AIDS-associated malignancies". Adv. Pharmacol. 56: 509–57. doi:. PMID 18086422.

- ^ Chumakov P, Iotsova V, Georgiev G (1982). "[Isolation of a plasmid clone containing the mRNA sequence for mouse nonviral T-antigen]". Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR 267 (5): 1272–5. PMID 6295732.

- ^ Oren M, Levine AJ (January 1983). "Molecular cloning of a cDNA specific for the murine p53 cellular tumor antigen". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80 (1): 56–9. PMID 6296874. PMC: 393308. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=6296874.

- ^ Baker SJ, Fearon ER, Nigro JM, Hamilton SR, Preisinger AC, Jessup JM, vanTuinen P, Ledbetter DH, Barker DF, Nakamura Y, White R, Vogelstein B (April 1989). "Chromosome 17 deletions and p53 gene mutations in colorectal carcinomas". Science (journal) 244 (4901): 217–21. doi:. PMID 2649981.

- ^ Maltzman W, Czyzyk L (1984). "UV irradiation stimulates levels of p53 cellular tumor antigen in nontransformed mouse cells". Mol Cell Biol 4 (9): 1689–94. PMID 6092932.

- ^ Kastan MB, Kuerbitz SJ (December 1993). "Control of G1 arrest after DNA damage". Environ. Health Perspect. 101 Suppl 5: 55–8. PMID 8013425.

- ^ Koshland DE (1993). "Molecule of the year". Science 262 (5142): 1953. doi:. PMID 8266084.

[edit] Additional images

|

The DAXX Pathway |

[edit] External links

- "p53 Knowledgebase". Lane Group at the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB), Singapore. http://p53.bii.a-star.edu.sg/. Retrieved on 2008-04-06.

- David S. Goodsell (2002-07-01). "p53 Tumor Suppressor". Molecule of the Month. RCSB Protein Data Bank. http://www.pdb.org/pdb/static.do?p=education_discussion/molecule_of_the_month/pdb31_2.html. Retrieved on 2008-04-06.

- Thierry Soussi. "p53 Web Site". http://p53.free.fr/. Retrieved on 2008-04-06.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||