Strasbourg

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Please expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French Wikipedia. (December 2008) After translating, {{Translated|fr|Strasbourg}} must be added to the talk page to ensure copyright compliance.Translation instructions · Translate via Google · Involve your language class |

| Ville de Strasbourg | ||

|

|

|

| City flag | City coat of arms | |

|

||

| Strasbourg Cathedral towering above the Old Town | ||

| Location | ||

|

||

| Time Zone | CET (UTC +1) | |

| Coordinates | ||

| Administration | ||

|---|---|---|

| Country | France | |

| Region | Alsace | |

| Department | Bas-Rhin | |

| Intercommunality | Strasbourg | |

| Mayor | Roland Ries (PS) | |

| Statistics | ||

| Elevation | 132–151 m (430–500 ft) | |

| Land area1 | 78.26 km2 (30.22 sq mi) | |

| Population2 | 276,867 (2006) | |

| - Ranking | 7th in France | |

| - Density | 3,538 /km² (9,160 /sq mi) | |

| Urban Spread | ||

| Urban Area | 222 km2 (86 sq mi) (2006[1]) | |

| - Population | 276,867 (2006[1]) | |

| Metro Area | 1,351.5 km2 (521.8 sq mi) (1999[1]) | |

| - Population | 702,412 estimate (2007[2]) | |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | ||

| 2 Population sans doubles comptes: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Strasbourg (French: Strasbourg, pronounced [stʁazbuʁ]; Alsatian: Strossburi, [ˈʃd̥rɔːsb̥uri]; German: Straßburg [ˈʃtʁaːsbʊʁk]) is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in northeastern France. With 702,412 inhabitants in 2007, its metropolitan area is the ninth largest in France. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capita of the Bas-Rhin department.

Strasbourg is the seat of several European institutions such as the Council of Europe (with its European Court of Human Rights, its European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and its European Audiovisual Observatory) and the Eurocorps as well as the European Parliament and the European Ombudsman of the European Union. Strasbourg is an important centre of manufacturing and engineering, as well as of road, rail, and river communications. The port of Strasbourg is the second largest on the Rhine after Duisburg, Germany[3]. The city is the seat of the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine.

Strasbourg's historic city centre, the Grande Île ("Grand Island"), was classified a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1988, the first time such an honor was placed on an entire city centre. Strasbourg is fused into the Franco-German culture, and although violently disputed throughout history has been a bridge of unity between France and Germany for centuries, especially through its University, currently the largest in France, and the co-existence of Catholic and Protestant culture.

Contents |

[edit] Etymology

The city's Gallicized name is of Germanic origin and means "Town (at the crossing) of roads". The modern Stras- is cognate to the German Straße / Strasse which itself is derived from Latin strata ("street"), while -bourg is cognate to the German -burg ("fortress, town, citadel"), the English borough and the French bourg ("village").

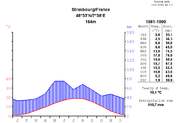

[edit] Geography and climate

Strasbourg is situated on the Ill River, where it flows into the Rhine on the border with Germany, across from the German town Kehl. The city is situated in the Rhine valley, approximately 20 km (12 mi) east of the Vosges Mountains and 25 km (16 mi) west of the Black Forest. Winds coming from either direction being often deflected by these natural barriers, the average annual precipitation is low[4] and the perceived summer temperatures can be inordinately high. The defective natural ventilation also makes Strasbourg one of the most atmospherically polluted cities of France[5][6], although the progressive disappearance of heavy industry on both banks of the Rhine, as well as effective measures of traffic regulation in and around the city are showing encouraging results.[7].

[edit] History

[edit] From Romans to Renaissance

At the site of Strasbourg, the Romans established a military outpost and named it Argentoratum. (Hence the town is commonly called Argentina in medieval Latin.[8]) It belonged to the Germania Superior Roman province. The name was first mentioned in the year 12 BC; the city celebrated its 2,000th birthday of continuous settlement in 1988. While the centre of Argentoratum proper was situated on the Grande Île (Cardo : current Rue du Dôme, Decumanus : current Rue des Hallebardes) most Roman artifacts have been found along the current Route des Romains in the suburb of Koenigshoffen, on the road that lead to it.[9] From the 4th century, Strasbourg was the seat of the Archbishopric of Strasbourg.

The Alemanni fought a Battle of Argentoratum against Rome in 357. They were defeated by Julian, later Emperor of Rome, and their king Chonodomarius was taken prisoner. On January 2, 366 the Alemanni crossed the frozen Rhine in large numbers, to invade the Roman Empire. Early in the 5th century the Alemanni appear to have crossed the Rhine, conquered, and then settled what is today Alsace and a large part of Switzerland.

The town was occupied successively in the 5th century by Alemanni, Huns, and Franks. In the 9th century it was commonly known as Strazburg in the local language, as documented in 842 by the Oaths of Strasbourg. This trilingual text is considered to contain, besides Latin and Old High German, also the oldest written variety of Gallo-Romance clearly distinct from Latin, the ancestor of Old French. The town was also called Stratisburgum or Strateburgus in Latin, Strossburi in Alsatian and Straßburg in Standard German, and then Strasbourg by the French.

A major commercial centre, the town came under control of the Holy Roman Empire in 923, through the homage paid by the Duke of Lorraine to German King Henry I. The early history of Strasbourg consists of a long conflict between its bishop and its citizens. The citizens emerged victorious after the Battle of Oberhausbergen in 1262, when King Philip of Swabia granted the city the status of an Imperial Free City.

Around 1200, Gottfried von Straßburg wrote the Middle High German courtly romance Tristan, which is regarded, alongside Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival and the Nibelungenlied, as one of great narrative masterpieces of the German Middle Ages.

A revolution in 1332 resulted in a broad-based city government with participation of the guilds, and Strasbourg declared itself a free republic. The murderous bubonic plague of 1348 was followed on February 14, 1349 by one of the first and worst pogroms in pre-modern history: several hundred Jews were publicly burnt to death, and the rest of them expelled from the city.[10] Until the end of the 18th century, Jews were forbidden to remain in town after 10 pm. The time to leave the city was signaled by a municipal herald blowing the Grüselhorn (see below, Museums, Musée historique)[11]; a high-pitched Cathedral bell still rings today. A special tax, the Pflastergeld (pavement money) was furthermore to be paid for any horse that a Jew would ride or bring into the city while allowed to[12].

Strasbourg Cathedral which began undergoing construction in the 12th century, was completed in 1439 (though only the north tower was built) and became the World's Tallest Building, surpassing the Great Pyramid of Giza. A few years later, Johannes Gutenberg created the first European moveable type printing press in Strasbourg.

In July 1518, an incident known as the Dancing Plague of 1518 struck residents of Strasbourg. Around 400 people were afflicted with dancing mania and danced constantly for weeks, most of them eventually dying from heart attack, stroke, or exhaustion.

In the 1520s during the Protestant Reformation, the city, under the political guidance of Jacob Sturm von Sturmeck and the spiritual guidance of Martin Bucer embraced the religious teachings of Martin Luther, whose adherents established a Gymnasium, headed by Johannes Sturm, made into a University in the following century. The city first followed the Tetrapolitan Confession, and then the Augsburg Confession. Protestant iconoclasm caused much destruction to churches and cloisters. Strasbourg was a centre of humanist scholarship and early book-printing in the Holy Roman Empire and its intellectual and political influence contributed much to the establishment of Protestantism as an accepted denomination in the southwest of Germany (John Calvin had spent several years as a political refugee in the city). Together with four other free cities, Strasbourg presented the confessio tetrapolitana as its Protestant book of faith at the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1530, where the slightly different Augsburg Confession was also handed over to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

After the reform of the Imperial constitution in the early 16th century and the establishment of Imperial Circles, Strasbourg was part of the Upper Rhenish Circle, a corporation of Imperial estates in the southwest of Holy Roman Empire, mainly responsible for maintaining troops, supervising coining, and ensuring public security.

After the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440, who had spent more than a decade in Strasbourg, the first printing offices anywhere outside the inventor's hometown Mainz were established around 1460 in the Alsatian capital by pioneers Johannes Mentelin and Heinrich Eggestein. Subsequently, the first modern newspaper was published in Strasbourg in 1605, when Johann Carolus received the permission by the City of Strasbourg to print and distribute a weekly journal written in German by reporters from several central European cities.

[edit] From Thirty Years' War to First World War

The Free City of Strasbourg remained neutral during the Thirty Years' War. In September 1681 it was annexed by King Louis XIV of France, whose unprovoked annexation was recognized by the Treaty of Ryswick (1697). The official policy of religious intolerance which drove many Protestants from France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1598) by the Edict of Fontainebleau (1685) was not applied in Strasbourg and in Alsace. Strasbourg Cathedral, however, was restored from the Lutherans to the Catholics. The German Lutheran university persisted until the French Revolution. Famous students were Goethe and Herder.

During a dinner in Strasbourg organized by Mayor Frédéric de Dietrich on April 25, 1792, Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle composed "La Marseillaise". However, Strasbourg's status as a free city was revoked by the French Revolution. Enragés, most notoriously Eulogius Schneider, ruled the city with an increasingly iron hand. During this time, many churches and cloisters were either destroyed or severely damaged. The cathedral lost hundreds of its statues (later replaced by copies in the 19th century) and in April 1794, there was talk of tearing its spire down, on the grounds that it hurt the principle of equality. The tower was saved, however, when in May of the same year citizens of Strasbourg crowned it with a giant tin Phrygian cap. This artifact was later kept in the historical collections of the city until they were all destroyed in 1870.[13]

With the growth of industry and commerce, the city's population tripled in the 19th century to 150,000. During the Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Strasbourg, the city was heavily bombarded by the Prussian army. On August 24, 1870, the Museum of Fine Arts was destroyed by fire, as was the Municipal Library housed in the Gothic former Dominican Church, with its unique collection of medieval manuscripts (most famously the Hortus deliciarum), rare Renaissance books, archeological finds and historical artifacts. In 1871 after the war's end, the city was annexed to the newly-established German Empire as part of the Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen (via the Treaty of Frankfurt) without a plebiscite. As part of Imperial Germany, Strasbourg was rebuilt and developed on a grand and representative scale (the Neue Stadt, or "new city"). Historian Rodolphe Reuss and Art historian Wilhelm von Bode were in charge of rebuilding the municipal archives, libraries and museums. The University, founded in 1567 and suppressed during the French Revolution as a stronghold of German sentiment, was reopened in 1872 under the name Kaiser-Wilhelms-Universität. A belt of massive fortifications was established around the city, most of which still stand today : Fort Roon (now Desaix) and Podbielski (now Ducrot) in Mundolsheim, Fort von Moltke (now Rapp) in Reichstett, Fort Bismarck (now Kléber) in Wolfisheim, Fort Kronprinz (now Foch) in Niederhausbergen, and Fort Grossherzog von Baden (now Frère) in Oberhausbergen.[14] Those forts subsequently served the French army, and were used as POW-camps in 1918 and 1945.

Following the defeat of Germany in World War I, the city was restored to France; city residents were again not offered a plebiscite.

[edit] Twentieth century and now

On November 11, 1918, communist insurgents proclaimed a "soviet government" in the city, following the example of Kurt Eisner in Munich as well as other German towns. The insurgency was brutally repressed on November 22; a major street of the city now bears the name of that date (Rue du 22 Novembre) [15]

Having been influenced by Germanic culture since the Frankish Realm, Strasbourg remained largely Alsatian-speaking well into the 20th century, and Germany continued to covet it under Nazi rule. Following the Fall of France in 1940 during World War II, the city was annexed by Nazi Germany. As one of the first official acts, the new rulers burnt and razed the main synagogue that had been a major architectural landmark and one of the largest in Europe since its completion in 1897.[16] After the war, Strasbourg was returned to France, and while the First World War did not notably damage the city, Anglo-American bombers caused extensive destruction in 1944 in raids of which at least one was allegedly carried out by mistake.[17] On November 23, 1944, the city was officially liberated by General Leclerc.[18] An unrelated tragedy that added, however, to the wartime losses, was the 1947 fire that destroyed a valuable part of the collection of the new Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1920, Strasbourg became the seat of the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine, previously located in Mannheim, one of the very first European institutions. In 1949, the city was chosen to be the seat of the Council of Europe with its European Court of Human Rights and European Pharmacopoeia. Since 1952, Strasbourg has been the official seat of the European Parliament, although only plenary sessions are held in Strasbourg each month, while all other business is being conducted in Brussels and Luxembourg. Those sessions take place in the Immeuble Louise Weiss, inaugurated in 1999, which houses the largest parliamentary assembly room in Europe and of any democratic institution in the world. Before that, the EP sessions had to take place in the main Council of Europe building, the Palace of Europe, whose unusual inner architecture had become a familiar sight to European TV audiences.[19] In 1992, Strasbourg became the seat of the Franco-German TV channel and movie-production society Arte.

In 2000, an Islamist plot to blow up the cathedral was prevented by German authorities.

On July 6, 2001, during an open-air concert in the Parc de Pourtalès, a single falling Platanus tree caused one of the worst disasters of its kind in history, killing thirteen people and injuring 97. On March 27, 2007, the city was found guilty of neglect over the accident and fined € 150,000.[20]

In 2006, after a long and careful restoration, the inner decoration of the Aubette, made in the 1920s by Hans Arp, Theo van Doesburg, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp and destroyed in the 1930s, was made accessible to the public again. The work of the three artists had been called "the Sistine Chapel of abstract art".[21]

[edit] Main sights

[edit] Architecture

The city is chiefly known for its sandstone Gothic Cathedral with its famous astronomical clock, and for its medieval cityscape of Rhineland black and white timber-framed buildings, particularly in the Petite-France district alongside the Ill and in the streets and squares surrounding the cathedral, where the renowned Maison Kammerzell stands out.

Notable medieval streets include Rue Mercière, Rue des Dentelles, Rue du Bain aux Plantes, Rue des Juifs, Rue des Frères, Rue des Tonneliers, Rue du Maroquin, Rue des Charpentiers, Rue des Serruriers, Grand' Rue, Quai des Bateliers, Quai Saint-Nicolas and Quai Saint-Thomas. Notable medieval squares include Place de la Cathédrale, Place du Marché Gayot, Place Saint-Etienne, Place du Marché aux Cochons de Lait and Place Benjamin Zix.

In addition to the cathedral, Strasbourg houses several other medieval churches that have survived the many wars and destructions that have plagued the city: the Romanesque Église Saint-Etienne, partly destroyed in 1944 by Anglo-American bombing raids, the part Romanesque, part Gothic, very large Église Saint-Thomas with its Silbermann organ on which Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Albert Schweitzer played [22], the Gothic Eglise Saint-Pierre-le-Jeune Protestant with its crypt dating back to the 7th century and its cloister partly from the 11th century, the Gothic Église Saint-Guillaume with its fine early-Renaissance stained glass and furniture, the Gothic Église Saint-Jean, the part Gothic, part Art Nouveau Église Sainte-Madeleine, etc The Neo-Gothic church Saint-Pierre-le-Vieux Catholique (there is also an adjacent church Saint-Pierre-le-Vieux Protestant) serves as a shrine for several 15th-century wood worked and painted altars coming from other, now destroyed churches and installed there for public display. Among the numerous secular medieval buildings, the monumental Ancienne Douane (old custom-house) stands out.

The German Renaissance has bequeathed the city some noteworthy buildings (especially the current Chambre de Commerce et d'Industrie, former town hall, on Place Gutenberg), as did the French Baroque and Classicism with several hôtels particuliers (i.e. palaces), among which the Palais Rohan (now housing three museums) is the most spectacular. Other buildings of its kind are the Hôtel du Préfet, the Hôtel des Deux-Ponts and the city-hall Hôtel de Ville etc. The largest baroque building of Strasbourg though is the 1720s main building of the Hôpital civil. As for French Neo-classicism, it is the Opera House on Place Broglie that most prestigiously represents this style.

Strasbourg also offers high-class eclecticist buildings in its very extended German district, being the main memory of Wilhelmian architecture since most of the major cities in Germany proper suffered intensive damage during World War II. Streets, boulevards and avenues are homogeneous, surprisingly high (up to seven stories) and broad examples of German urban lay-out and of this architectural style that summons and mixes up five centuries of European architecture as well as Neo-Egyptian, Neo-Greek and Neo-Babylonian styles. The former imperial palace Palais du Rhin, the most political and thus heavily criticized of all German Strasbourg buildings epitomizes the grand scale and stylistic sturdiness of this period. But the two most handsome and ornate buildings of these times are the École internationale des Pontonniers (the former Höhere Mädchenschule, girls college) with its towers, turrets and multiple round and square angles [23] and the École des Arts décoratifs with its lavishly ornate facade of painted bricks, woodwork and majolica [24].

Notable streets of the German district include: Avenue de la Forêt Noire, Avenue des Vosges, Avenue d'Alsace, Avenue de la Marseillaise, Avenue de la Liberté, Boulevard de la Victoire, Rue Sellénick, Rue du Général de Castelnau, Rue du Maréchal Foch, and Rue du Maréchal Joffre. Notable squares of the German district include: Place de la République, Place de l'Université, Place Brant, and Place Arnold

Impressive examples of Prussian military architecture of the 1880s can be found along the newly reopened Rue du Rempart, displaying large scale fortifications among which the aptly named Kriegstor (war gate).

As for modern and contemporary architecture, Strasbourg possesses some fine Art Nouveau buildings (the huge Palais des Fêtes, some houses and villas on Avenue de la Robertsau and Rue Sleidan), good examples of post-World War II functional architecture (the Cité Rotterdam, for which Le Corbusier did not succeed in the architectural contest) and, in the very extended Quartier Européen, some spectacular administrative buildings of sometimes utterly large size, among which the European Court of Human Rights by Richard Rogers is arguably the finest. Other noticeable contemporary buildings are the new Music school Cité de la Musique et de la Danse, the Musée d'Art moderne et contemporain and the Hôtel du Département facing it, as well as, in the outskirts, the tramway-station Hoenheim-Nord designed by Zaha Hadid.

The city is also home to many bridges, including the medieval, four-towered Ponts Couverts.

Next to it is a part of the 17th-century Vauban fortifications, the Barrage Vauban. Other nice bridges are the ornate 19th-century Pont de la Fonderie (1893, stone) and Pont d'Auvergne (1892, iron), as well as architect Marc Mimram's futuristic Passerelle over the Rhine, opened in 2004.

The largest square at the centre of the city of Strasbourg is the Place Kléber. Located in the heart of the city’s commercial area, it was named after general Jean-Baptiste Kléber, born in Strasbourg in 1753 and slaughtered in 1800 in Cairo. In the square is a statue of Kléber, under which is a vault containing his remains. On the north side of the square is the Aubette (Orderly Room), built by Jacques François Blondel, architect of the king, in 1765-1772.

[edit] Parks

Strasbourg features a number of prominent parks, of which several are of cultural and historical interest: the Parc de l'Orangerie, laid out as a French garden by André le Nôtre and remodeled as an English garden on behalf of Joséphine de Beauharnais, now displaying noteworthy French gardens, a neo-classical castle and a small zoo; the Parc de la Citadelle, built around impressive remains of the 17th-century fortress erected close to the Rhine by Vauban [25]; the Parc de Pourtalès, laid out in English style around a baroque castle (heavily restored in the 19th century) that now houses the Schiller International University, and featuring an open-air museum of international contemporary sculpture [26]. The Jardin botanique de l'Université de Strasbourg (botanical garden) was created under the German administration next to the Observatory of Strasbourg, built in 1881, and still owns some greenhouses of those times. The Parc des Contades, although the oldest park of the city, was completely remodeled after World War II. The futuristic Parc des Poteries is an example of European park-conception in the late 1990s. The Jardin des deux Rives, spread over Strasbourg and Kehl on both sides of the Rhine, is the most recent (2004) and most extended (60 hectare) park of the agglomeration.

[edit] Museums

For a city of comparatively small size, Strasbourg displays a large quantity and variety of museums:

[edit] Art museums

Unlike most other cities, Strasbourg's collections of European art are divided into several museums according not only to type and area, but also to epoch. Old master paintings from the Germanic Rhenish territories and until 1681 are displayed in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, old master paintings from all the rest of Europe (including the Dutch Rhenish territories) and until 1871 as well as old master paintings from the Germanic Rhenish territories between 1681 and 1871 are displayed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts. Decorative arts until 1681 ("German period") are displayed in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, decorative arts from 1681 to 1871 ("French period") are displayed in the Musée des Arts décoratifs. International art and decorative art since 1871 is displayed in the Musée d'art moderne et contemporain.

- The Musée des Beaux-Arts owns paintings by Hans Memling, Francisco de Goya, Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Giotto di Bondone, Sandro Botticelli, Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, El Greco, Correggio, Cima da Conegliano and Piero di Cosimo, among others.

- The Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame (located in a part-Gothic, part-Renaissance building next to the Cathedral) houses a large and renowned collection of medieval and Renaissance upper-Rhenish art, among which original sculptures, plans and stained glass from the Cathedral and paintings by Hans Baldung and Sebastian Stoskopff.

- The Musée d'Art moderne et contemporain is among the largest museums of its kind in France.

- The Musée des Arts décoratifs, located in the sumptuous former residence of the cardinals of Rohan, the Palais Rohan displays a reputable collection of 18th century furniture and china.

- The Cabinet des estampes et des dessins displays five centuries of engravings and drawings, but also woodcuts and lithographies.

- The Musée Tomi Ungerer/Centre international de l’illustration, located in a large former villa next to the Theatre, displays original works by Ungerer and other artists (Saul Steinberg, Ronald Searle...) as well as Ungerer's large collection of ancient toys.

[edit] Other museums

- The Musée archéologique presents a vast display of regional findings from the first ages of man to the 6th century, focussing especially on the Roman and Celtic period.

- The very large Musée alsacien is dedicated to every aspects of traditional Alsatian daily life.

- The Musée zoologique is one of the oldest in France and is especially famous for its gigantic collection of birds.

- Le Vaisseau ("The vessel") is a science and technology centre, especially designed for children.

- The Musée historique (historical museum) is dedicated to the tumultuous history of the city and displays many artifacts of the times. It previously displayed the Grüselhorn, the medieval horn that was blown every evening at 10 to order the Jews out of the city, but this item was accidentally dropped and shattered into many small fragments and thus is no longer displayed.

- The Musée de la Navigation sur le Rhin, also going by the name of Naviscope, located in an old ship, is dedicated to the history of commercial navigation on the Rhine.

- The Musée de Sismologie et Magnétisme terrestre,

- the Musée Pasteur,

- the Musée de minéralogie and

- The Musée d'Égyptologie[27] are all three part of the University and only open to public some hours a week.

[edit] Demographics

The metropolitan area of Strasbourg includes 702,412 inhabitants (2007), while the Eurodistrict had 868,000 inhabitants in 2005.[28]

| 1684 | 1789 | 1851 | 1871 | 1910 | 1921 | 1936 | 1946 | 1954 | 1962 | 1968 | 1975 | 1982 | 1990 | 1999 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22 000 | 49 943 | 75 565 | 85 654 | 178 891 | 166 767 | 193 119 | 175 515 | 200 921 | 228 971 | 249 396 | 253 384 | 248 712 | 252 338 | 264 115 | 276 867 |

[edit] Culture

Strasbourg is the seat of some internationally reputed institutions in the musical and dramatic domain:

- The philharmonic orchestra Orchestre philharmonique de Strasbourg, founded in 1855, one of the oldest symphonic orchestras in western Europe.

- The Opéra national du Rhin

- The Théâtre national de Strasbourg

- The Percussions de Strasbourg

- The Théâtre du Maillon

- The "Laiterie"

Other theatres are the Théâtre jeune public, the TAPS Scala, the Kafteur...

[edit] Events

- Musica, international festival of contemporary classical music (autumn)

- Festival international de Strasbourg (founded in 1932), festival of classical music and jazz (summer)

- Festival des Artefacts, festival of contemporary non-classical music

- Les Nuits de l'Ososphère

- The Spectre Film Festival is an annual film festival that is devoted to science fiction, horror and fantasy.

[edit] Education

[edit] Universities and schools

Strasbourg, which was a humanism centre, has a long history of higher-education excellence, merging French and German intellectual traditions. Although Strasbourg had been annexed by the Kingdom of France in 1683, it still remained connected to the German-speaking intellectual world throughout the 18th century and the university attracted numerous students from the Holy Roman Empire, including Goethe, Metternich and Montgelas, who studied law in Strasbourg, among the most prominent. Nowadays, Strasbourg is known to offer among the best university courses in France, after Paris.

Until January 2009 there were three universities in Strasbourg, with an approximate total of 48,500 students as of 2007 (another 4,500 students are being taught at one of the diverse post-graduate schools)[29]:

- Strasbourg I - Louis Pasteur University

- Strasbourg II - Marc Bloch University

- Strasbourg III - Robert Schuman University

Since 1st January 2009, those three universities have merged and constitute now the Université de Strasbourg.

The prestigious Institut d'études politiques de Strasbourg (Sciences Po Strasbourg) is part of the University of Strasbourg.

The campus of the École nationale d'administration (ENA) is located in Strasbourg (the former one being in Paris). The location of the "new" ENA - which trains most of the nation's high-ranking civil servants - was meant to give a European vocation to the school.

The École supérieure des Arts décoratifs (ESAD) is an art school of Europe-wide reputation.

The permanent campus of the International Space University (ISU) is located in the south of Strasbourg (Illkirch-Graffenstaden)

Other important schools include the INSA (Institut national des sciences appliquées), the ECPM (École européenne de chimie, polymères et matériaux), the INET (Institut national des études territoriales), the ENGEES (École nationale du génie de l'eau et de l'environnement de Strasbourg), and the CUEJ (Centre universitaire d'enseignement du journalisme).

[edit] Libraries

The Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire (BNU) is, with its collection of more than 3,000,000 titles [30], the second largest library in France after the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It was founded by the German administration after the complete destruction of the previous municipal library in 1871 and holds the unique status of being simultaneously a student's and a national library.

The municipal library Bibliothèque municipale de Strasbourg (BMS) administrates a network of ten medium-sized librairies in different areas of the town. A six stories high "Grande bibliothèque", the Médiathèque André Malraux, was inaugurated on September 19, 2008 and is considered the largest in Eastern France.[31]

[edit] Incunabula

As one of the earliest centers of book-printing in Europe (see above: History), Strasbourg for a long time held a large number of incunabula in her library as one of her most precious heritages. After the total destruction of this institution in 1870, however, a new collection had to be reassembled from scratch. Today, Strasbourg's different public and institutional libraries again display a sizeable total number of incunabula, distributed as follows: Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire, 2 000 [32]; Médiathèque de la ville et de la communauté urbaine de Strasbourg, 349 [33]; Bibliothèque du Grand Séminaire, 257 [34]; Médiathèque protestante, circa 100 [35] and Bibliothèque alsatique du Crédit Mutuel, 5. [36]

[edit] Transport

Strasbourg has its own airport, serving a limited number of destinations. Train services operate eastward to Offenburg and Karlsruhe in Germany, westward to Metz and Paris, and southward to Basel. Since June 10, 2007, Strasbourg is linked to the European high-speed train network by the TGV Est (Paris-Strasbourg). The TGV Rhin-Rhône (Strasbourg-Lyon) is currently under construction and due to open in 2012.

City transportation in Strasbourg is served by a modern-looking tram system that has been operated since 1994 by the regional transit company Compagnie des transports strasbourgeois. A former tram system, partly following different routes, had been operating since 1878 but was ultimately dismantled in 1960.

Being a city next to the Rhine and along some of its most important canals (Marne-Rhine Canal, Grand Canal d'Alsace), while crossed by the Ill, Strasbourg has always been an important centre of fluvial navigation, as is attested by archeological findings as well as the important activity of the Port autonome de Strasbourg. Water tourism inside the city proper attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists yearly.

[edit] European role

[edit] Institutions

Strasbourg is the seat of over twenty international institutions [37], most famously of the Council of Europe and of the European Parliament, of which it is the official seat. Strasbourg is considered the legislative and democratic capital of the European Union, while Brussels is considered the executive and administrative capital and Luxembourg the judiciary and financial capital.[citation needed]

Strasbourg is:

- since 1920 the seat of the Central Commission for Navigation on the Rhine.

- since 1949 the seat of the Council of Europe with all the bodies and organisations affiliated to this institution

- since 1952 the seat of the European Parliament

- the seat of the European Ombudsman

- the seat of the Eurocorps headquarters,

- the seat of the Franco-German television channel Arte

- the seat of the European Science Foundation

- the seat of the International Institute of Human Rights

- the seat of the Human Frontier Science Program

- the seat of the International Commission on Civil Status

- the seat of the Assembly of European Regions

- the seat of the Centre for European Studies

[edit] Eurodistrict

France and Germany have created a Eurodistrict straddling the Rhine, combining the Greater Strasbourg and the Ortenau district of Baden-Württemberg, with some common administration. The combined population of this district was 868,000 as of 2006. [28]

[edit] Sports

Internationally-renowned teams from Strasbourg are the "Racing Club de Strasbourg" (football), the "SIG" (basketball) and the "Étoile Noire" (hockey)[38]. The women's tennis tournament "Internationaux de Strasbourg" is one of the most important French tournaments of its kind outside Roland-Garros.

[edit] Notable people

In chronological order, notable people born in Strasbourg include: Johannes Tauler, Sebastian Brant, Jean Baptiste Kléber, Louis Ramond de Carbonnières, Marie Tussaud, Ludwig I of Bavaria, Charles Frédéric Gerhardt, Gustave Doré, Émile Waldteufel, Jean/Hans Arp, Charles Münch, Hans Bethe, Marcel Marceau, Tomi Ungerer, Arsène Wenger and Petit.

In chronological order, notable residents of Strasbourg include: Johannes Gutenberg, Hans Baldung, Martin Bucer, John Calvin, Joachim Meyer, Johann Carolus, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz, Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, Georg Büchner, Louis Pasteur, Ferdinand Braun, Albrecht Kossel, Georg Simmel, Albert Schweitzer, Otto Klemperer, Marc Bloch, Alberto Fujimori, Paul Ricoeur and Jean-Marie Lehn.

[edit] Twin towns

Strasbourg is twinned with:

Boston, United States (since 1960)

Boston, United States (since 1960) Leicester, United Kingdom (since 1960)

Leicester, United Kingdom (since 1960) Stuttgart, Germany (then West-Germany) (since 1962)

Stuttgart, Germany (then West-Germany) (since 1962) Dresden, Germany (then East-Germany) (since 1990)[39]

Dresden, Germany (then East-Germany) (since 1990)[39] Ramat Gan, Israel (since 1991)

Ramat Gan, Israel (since 1991) Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey Jacmel, Haiti (since 1996) (Coopération décentralisée)

Jacmel, Haiti (since 1996) (Coopération décentralisée) Novgorod, Russia (since 1997) (Coopération décentralisée)

Novgorod, Russia (since 1997) (Coopération décentralisée) Fes, Morocco (Coopération décentralisée)

Fes, Morocco (Coopération décentralisée)

[edit] Strasbourg in popular culture

- On Roy Hargrove's new album "Earfood" (2008), he recorded a song called "Strasbourg\St. Denis" which is based on the city.

- One of the longest chapters of Laurence Sterne's novel Tristram Shandy ("Slawkenbergius's tale") takes place in Strasbourg.[40]

- An episode of Matthew Gregory Lewis's novel The Monk takes place in the forests then surrounding Strasbourg.

- British art-punk band The Rakes had a minor hit in 2005 with, their song "Strasbourg". This song features witty lyrics with themes of espionage and vodka and includes a cleverly-placed count of 'eins, zwei, drei, vier!!', even though Strasbourg's most common spoken language is French.

- On their 1974 album Hamburger Concerto, Dutch progressive band Focus included a track called "La Cathédrale de Strasbourg", which included chimes from a cathedral-like bell.

- The 2008 film In the city of Sylvia is set in Strasbourg.

[edit] See also

- Strasbourg Cathedral

- University of Strasbourg

- Observatory of Strasbourg

- Palace of Europe

- Seat of the European Parliament in Strasbourg

- Strasbourg Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

- Strasbourg Convention (Patent law)

- List of mayors of Strasbourg

- Strasbourg IG

- History of Jews in Alsace

- Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire

- Christkindelsmärik, Strasbourg

- Communes of the Bas-Rhin department

[edit] References

- ^ a b c Only the part of the metropolitan area on French territory.

- ^ Only the part of the metropolitan area on French territory. The population for the entire metropolitan area across both French and German territory (town of Kehl) was 702,412 in 2007.

- ^ Figures on the port's website

- ^ Annual rain in Strasbourg

- ^ Daily measurements for Strasbourg and Alsace

- ^ Measurements made on October 18 and October 19, 2005

- ^ OUTLINES OF THE URBAN TRANSPORTATION POLICY LEAD BY THE URBAN COMMUNITY OF STRASBOURG

- ^ Graesse, Orbis Latinus

- ^ Map of archological findings in Koenigshoffen

- ^ (French) The "Valentine's day massacre" of 1349

- ^ (French) The Jews of Strasbourg and the Great Plague

- ^ (French) The Jews of Strasbourg until the French Revolution

- ^ Strasbourg Cathedral and the French Revolution (1789-1802)

- ^ Partial plan

- ^ 11 novembre 1918: le drapeau rouge flotte sur Strasbourg

- ^ History and pictures of the Synagogue du Quai Kléber

- ^ "Civilians on the frontline ? Allied aerial bombings in northeastern France, 1940-1945"

- ^ Pictures of Strasbourg in ruins after the 1944 bombing raids

- ^ View of the assembly room

- ^ City of Strasbourg fined in storm death

- ^ Reopening of the restored rooms

- ^ History and description of the instrument

- ^ Pictures

- ^ Views

- ^ Parc de la Citadelle with remains of the Vauban fortress

- ^ Overview

- ^ Overview of the collections

- ^ a b Figures on the Eurodistrict's website

- ^ Figures

- ^ Figures

- ^ Strasbourg ouvre une grande médiathèque sur le port in L'Express (French)

- ^ http://www.bnu.fr/BNU/FR/Poles+Documentaires/Patrimoine/Incunables.htm

- ^ http://www.mediatheques-cus.fr/medias/medias.aspx?INSTANCE=exploitation&PORTAL_ID=erm_portal_003.xml&SYNCMENU=003

- ^ http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=3736520

- ^ http://www.epal.fr/mediatheque/textes/historique.htm

- ^ http://www.bacm.creditmutuel.fr/FONDS_ANCIEN.html

- ^ List of international institutions in Strasbourg

- ^ Etoile Noire de Strasbourg

- ^ "Dresden - Partner Cities". © 2008 Landeshauptstadt Dresden. http://www.dresden.de/en/02/11/c_03.php. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ Full text

[edit] References

- Connaître Strasbourg by Roland Recht, Georges Foessel and Jean-Pierre Klein, 1988, ISBN 2-7032-0185-0

- Histoire de Strasbourg des origines à nos jours, four volumes (ca. 2000 pages) by a collective of historians under the guidance of Georges Livet and Francis Rapp, 1982, ISBN 2-7165-0041-X

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Strasbourg |

- Strasbourg official website

- Strasbourg in the Structurae database

- Eurodistrict official site (French) (German)

- Port of Strasbourg (French)

- Webcam of Strasbourg

- The museums of Strasbourg (French) + some English

- The city archives of Strasbourg (French)

- The European institutions in Strasbourg

- Education network for universities and high schools at Strasbourg (French)

- National Theater of Strasbourg (Théâtre National de Strasbourg)

- The Opéra du Rhin

- The Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra (French)

- The Strasbourg Art School (French)

- The National and University Library (French)

- The organs of Strasbourg (French)

- English Speaking Community of Strasbourg

- Visiting Strasbourg

- Photos through the city (French)

- Public transport in Strasbourg

- Strasbourg travel guide from Wikitravel

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||