Renaissance humanism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Renaissance humanism was a European intellectual movement that was a crucial component of the Renaissance, beginning in Florence in the last years of the 14th century. The humanist movement developed from the rediscovery by European scholars of classical Latin and later Greek texts. Initially, a humanist was simply a scholar or teacher of Latin literature. By the mid-15th century humanism described a curriculum — the studia humanitatis — comprising grammar, rhetoric, moral philosophy, poetry and history as studied via classical authors. Humanists mostly believed that, although God created the universe, it was humans that had developed and industrialized it. Beauty, a popular topic, was held to represent a deep inner virtue and value, and an essential element in the path towards God.

The humanists were often opposed to philosophers of the preceding movement of Scholasticism, the "schoolmen" of the universities of Italy, Paris, Oxford and elsewhere. The scholastics' methodology was also derived from the classics, especially Thomas Aquinas' synthesis of the thought of Aristotle, and a classical debate which referred back to Plato and the Platonic dialogues was revived.

Contents |

[edit] History

In the 1480s, Giovanni Pico della Mirandola wrote a [preface] to the nine hundred page thesis that he submitted for public debate entitled An Oration on the Dignity of Man. The debate never took place, but the work became a seminal text in the development of humanism. In it, he talked about how God created man and that man's greatness comes from God. He said that man was like a chameleon; which meant that he could become whatever he wanted to be.

Humanists placed a heavy emphasis on the study of primary sources rather than the study of the interpretations of others. This is reflected in their motto of ad fontes, or "to the sources" which informed the search for texts in the monastery libraries of Europe. Humanist education, called the studia humanista or studia humanitatis (study of humanity), concentrated on the study of the liberal arts: Latin and Greek grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy or ethics, and history.

Early 15th-century humanists were interested in classical Latin and not in medieval Latin, which was a different and more developed language with many neologisms. Petrarch, sometimes called the father of Renaissance humanism in Italy, called the Latin of the Middle Ages "barbarous;" when he collected his "Familiar Letters" his model was Cicero and his model for Latin was that used by Virgil, who was emerging from the persona as a magus that had accrued in the Middle Ages. This new interest in the classical literature led to the scouring of monastic libraries across Europe for lost texts. One such hunt by [Poggio Bracciolini], who was credited with the discovery of the complete works of fifteen different authors, turned up Vitruvius' work on art and architecture, allowing for the completion of the Duomo of Florence by Filippo Brunelleschi.

The central feature of humanism in this period was the commitment to the idea that the ancient world (defined effectively as ancient Greece and Rome, which included the entire Mediterranean basin) was the pinnacle of human achievement, especially intellectual achievement, and should be taken as a model by contemporary Europeans. According to this view of history, the fall of Rome to Germanic invaders, in the fifth century, had led to the dissolution and decline of this remarkable culture; the intellectual heritage of the ancient world had been lost—many of its most important books had been destroyed and dispersed—and a thousand years later, Europeans were still living in the ghetto. The only way in which Europeans could expect to pull themselves out of this intellectual catastrophe was to attempt to recover, edit, and make available these lost texts, which included, among others, almost all the works of Plato. (In the process, Greek texts had to be translated into Latin, the language of intellectuals and the learned.) This enterprise, launched through the reintroduction of Greek to Italy by Manuel Chrysoloras, generated enormous enthusiasm, and the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were devoted to this project.

Humanism offered the necessary intellectual and philological tools for the first dispassionate analysis of texts. An early triumph of textual criticism by Lorenzo Valla revealed the Donation of Constantine to be an early medieval forgery produced in the Curia. This textual criticism began to create real political controversy when Erasmus began to apply it to biblical texts, in his Novum Instrumentum.

The crisis of Renaissance humanism came with the trial of Galileo which was centered on the choice between basing the authority of one's beliefs on one's observations, or upon religious teaching. The root of the conflict was the Biblical teaching that "The truth will set you free" [1] which was the heart of the emerging Christian teaching methodology. The basic principle is that all observations must be documented and verifiable, that is, true. The method was implemented in Europe through Jesuit schools and the Medieval universities, and eventually forced many contradictions to the surface. The trial of Galileo made the contradictions between humanism and traditional religion visibly apparent to all. Although Pope Urban VIII was sympathetic to Galileo, even asking Galileo to ensure that both sides of the argument were presented for academic discussion, Galileo proceeded to publish a one-sided advocacy, thereby causing great distress and conflict within both sides of the argument[2]. This conflict has greatly influenced modern academic science to this day[3].

[edit] Social or civic humanism

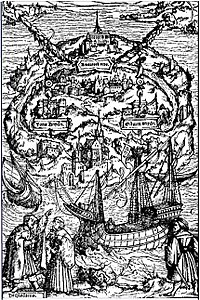

Illuminated manuscript by Simone Martini, 29 x 20 cm Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan.

Social or civic humanism rose out of the republican ideology of Florence at the beginning of the fifteenth century. It sought to create citizens capable of participating in the civic life of their community by placing central emphasis on human autonomy. Leonardo Bruni's Panegyric is one expression of this philosophy. The emancipated and literate upper bourgeoisie of the independent Italian communes adapted 14th-century Burgundian aristocratic culture and manners to an intensely patriotic civic life. Humanism was a pervasive cultural mode, not merely the product of a handful of geniuses, like Giotto or Leon Battista Alberti.

[edit] Beliefs

Renaissance humanists believed that the liberal arts (art, music, grammar, rhetoric, oratory, history, poetry, using classical texts, and the studies of all of the above) should be practiced by all levels of "richness". They also approved of self, human worth and individual dignity. They hold the belief that everything in life has a determinate nature, but man's privilege is to be able to choose his own nature. Pico della Mirandola wrote the following concerning the creation of the universe and man's place in it:

| “ | But when the work was finished, the Craftsman kept wishing that there were someone to ponder the plan of so great a work, to love its beauty, and to wonder at its vastness. Therefore, when everything was done... He finally took thought concerning the creation of man... He therefore took man as a creature of indeterminate nature and, assigning him a place in the middle of the world, addressed him thus: "Neither a fixed abode nor a form that is thine alone nor any function peculiar to thyself have we given thee, Adam, to the end that according to thy longing and according to thy judgement thou mayest have and possess what abode, what form and what functions thou thyself shalt desire. The nature of all other beings is limited and constrained within the bounds of law. Thou shalt have the power to degenerate into the lower forms of life, which are brutish. Thou shalt have the power, out of thy soul's judgement, to be born into the higher forms, which are divine." (Pico 224-225) | ” |

Humanists believe that such possibilities lead to the diverse ways of human development. Value is given to this uniqueness and encourages individualism.

[edit] Relationship to Christianity

As Neo-Platonism replaced the Aristotelianism of Saint Thomas Aquinas, attempts were made to join the great works of Antiquity with Christian values in a syncretic Christian humanism, such as those by Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola. Ethics was taught independently of theology, and the authority of the Church was tacitly transferred to the reasoning logic of the educated individual. Thus humanists constantly skirted the dangers of being branded as heretics.

One example of such pagan philosophy and Christian doctrine melding is found in The Epicurean, by Erasmus, the "prince of humanists:"

- If people who live agreeably are Epicureans, none are more truly Epicurean than the righteous and godly. And if it's names that bother us, no one better deserves the name of Epicurean than the revered founder and head of the Christian philosophy Christ, for in Greek epikouros means "helper." He alone, when the law of Nature was all but blotted out by sins, when the law of Moses incited to lists rather than cured them, when Satan ruled in the world unchallenged, brought timely aid to perishing humanity. Completely mistaken, therefore, are those who talk in their foolish fashion about Christ's having been sad and gloomy in character and calling upon us to follow a dismal mode of life. On the contrary, he alone shows the most enjoyable life of all and the one most full of true pleasure. (Erasmus 549)

This passage exemplifies the way in which the humanists saw pagan classical works such as the philosophy of Epicurus as being fundamentally in harmony with Christianity, rather than as a nemesis to be pitted against Christianity. Although Renaissance humanists were more accepting of pagan philosophy than their Scholastic contemporaries, they did not necessarily object to the idea that Christian understanding should be dominant over other modes of thought. Many humanists were churchmen, most notably Pope Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini Pius II, Sixtus IV, and Leo X,[4][5] and there was often patronage of humanists by senior church figures.[6] Much humanist effort went into improving the understanding and translations of Biblical and Early Christian texts, both before the Protestant Reformation, on which the work of figures like Erasmus and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples had a great influence, and afterwards.

As humanists increasingly opposed the strict Catholic orthodoxy of Scholastic philosophy, some began to intermingle pagan virtues with Christian virtues, and revive religious ideas from the late-classical Greek world, and some risked being declared heretics for distancing themselves from the church.[7] The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy describes the secularistic flavor of classical writings as having tremendous impact on Renaissance scholars:

Here, one felt no weight of the supernatural pressing on the human mind, demanding homage and allegiance. Humanity—with all its distinct capabilities, talents, worries, problems, possibilities—was the center of interest. It has been said that medieval thinkers philosophized on their knees, but, bolstered by the new studies, they dared to stand up and to rise to full stature.[8]

Renaissance humanism's divergence from orthodox Christianity was in two broad directions. Firstly there was Renaissance Neo-Platonism and Hermeticism, which through humanists like Giordano Bruno, Marsilio Ficino, Campanella and Pico della Mirandola introduced new and wide-ranging ideas of supernatural forces, and sometimes came close to constituting a new religion itself. Secondly, and especially towards the end of the movement, there was the secular world-view of humanist-influenced writers such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini, the agnosticism and skepticism of Francis Bacon and Michel Montaigne, and the anti-clerical satire of François Rabelais[9]. Of these two directions, the latter has had great continuing influence in Western thought, while the former mostly dissipated as an intellectual trend, leading to movements in Western esotericism such as Theosophy and New Age thinking.[10] The "Yates thesis" of Frances Yates holds that before falling out of favour, esoteric Renaissance thought introduced several concepts that were useful for the development of scientific method, though this remains a matter of controversy.

Though humanists continued to use their scholarship in the service of the church into the middle of the sixteenth century, the sharply confrontational religious atmosphere following the Protestant reformation resulted in the Counter-Reformation that sought to silence all challenges to Catholic theology,[11] with similar efforts among the Protestant churches.

The historian of the Renaissance Sir John Hale cautions against too direct a linkage between Renaissance humanism and modern uses of the term:"Renaissance humanism must be kept free from any hint of either "humanitarianism" or "humanism" in its modern sense of rational, non-religious approach to life ... the word "humanism" will mislead ... if it is seen in opposition to a Christianity its students in the main wished to supplement, not contradict, through their patient excavation of the sources of ancient God-inspired wisdom"[12]

[edit] Humanists

[edit] See also

- Renaissance

- Legal humanists

- Humanist Latin

- Humanism in Germany

- Scholasticism

- Humanism

- Greek scholars in the Renaissance

- New Learning

[edit] Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Finocchiaro (2007)

- ^ Löffler, Klemens (1910). "Humanism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. VII. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 538-542.

- ^ Origo, Iris; in Plumb, pp. 209ff. See also their respective entries in Hale, 1981

- ^ Davies, 477

- ^ "Humanism". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Religion. F-N. Corpus Publications. 1979. pp. 1733. ISBN 0-9602572-1-7.

- ^ ""Humanism"". "The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Second Edition. Cambridge University Press. 1999.

- ^ Kreis, Steven (2008). "Renaissance Humanism". http://www.historyguide.org/intellect/humanism.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-03.

- ^ Plumb, 95

- ^ "Rome Reborn: The Vatican Library & Renaissance Culture: Humanism". The Library of Congress. 2002-07-01. http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/vatican/humanism.html. Retrieved on 2009-03-03.

- ^ Hale, 171. See also Davies, 479-480 for similar caution.

[edit] References and external links

- Celenza, Christopher S. The Lost Italian Renaissance: Humanism, Historians, and Latin's Legacy. Johns Hopkins University Press. 2004 ISBN 978-0-8018-8384-2

- Davies, Norman, Europe: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- Dictionary of the History of ideas: "Renaissance Humanism"

- Erasmus, "The Epicurean," in Colloquies.

- Hale, John. A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance, Oxford University Press, 1981, ISBN 0500233330.

- Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Oration on the Dignity of Man, in Cassirer, Kristeller, and Randall, Renaissance Philosophy of Man.

- Catholic Encyclopedia article

- Dictionary of the History of ideas: Renaissance Idea of the Dignity of Man"

- Kreis, Steven: "Renaissance Humanism

- Stuart M. McManus, 'Byzantines in the Florentine polis: Ideology, Statecraft and ritual during the Council of Florence', Journal of the Oxford University History Society, 6 (Michaelmas 2008/Hilary 2009)

- Melchert, Norman (2002). The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-19-517510-7.

- Plumb, J.H. ed.: The Italian Renaissance 1961, American Heritage, New York, ISBN 0-618-12738-0 (page refs from 1978 UK Penguin edn).