Patrice Lumumba

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Patrice Lumumba

|

|

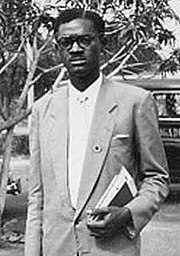

Patrice Lumumba as the Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, 1960 |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 24 June 1960 – 14 September 1960 |

|

| Deputy | Antoine Gizenga |

| Preceded by | Colonial government |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Ileo |

|

|

|

| Born | 2 July 1925 Onalua, Katakokombe, Belgian Congo |

| Died | 17 January 1961 (aged 35) Elisabethville, Katanga |

| Political party | MNC |

Patrice Émery Lumumba (2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was an African anti-colonial leader and the first legally elected Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo after he helped to win its independence from Belgium in June 1960. Only ten weeks later, Lumumba's government was deposed in coup during the Congo Crisis. He was subsequently imprisoned and murdered in controversial circumstances.

Contents |

[edit] Path to Prime Minister

Lumumba was born in Onalua in the Katakokombe region of the Kasai province of the Belgian Congo, a member of the Tetela ethnic group. Raised in a Catholic family as one of four sons, he was educated at a Protestant primary school, a Catholic missionary school, and finally the government post office training school, passing the one-year course with distinction. He subsequently worked in Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) and Stanleyville (now Kisangani) as a postal clerk and as a travelling beer salesman. In 1951, he married Pauline Opangu. In 1955, Lumumba became regional head of the Cercles of Stanleyville and joined the Liberal Party of Belgium, where he worked on editing and distributing party literature. After traveling on a three-week study tour in Belgium, he was arrested in 1955 on charges of embezzlement of post office funds. His two-year sentence was commuted to twelve months after it was confirmed by Belgian lawyer Jules Chrome that Lumumba had returned the funds, and he was released in July 1956. After his release, he helped found the non-tribal Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) in 1958, later becoming the organization's president. Lumumba and his team represented the MNC at the All-African People's Conference in Accra, Ghana, in December 1958. At this international conference, hosted by influential Pan-African President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Lumumba further solidified his Pan-Africanist beliefs.

In late October 1959, Lumumba as leader of the MNC was again arrested for allegedly inciting an anti-colonial riot in Stanleyville where thirty people were killed, for which he was sentenced to six months in prison. The trial's start date of 18 January 1960, was also the first day of a round-table conference in Brussels to finalize the future of the Congo. Despite Lumumba's imprisonment at the time, the MNC won a convincing majority in the December local elections in the Congo. As a result of pressure from delegates who were enraged at Lumumba's imprisonment, he was released and allowed to attend the Brussels conference. The conference culminated on 27 January with a declaration of Congolese independence setting 30 June 1960, as the independence date with national elections from 11-25 May 1960. Lumumba and the MNC won this election and the right to form a government, with the announcement on 23 June 1960 of 35-year-old Lumumba as Congo's first prime minister and Joseph Kasa-Vubu as its president. In accordance with the constitution, on 24 June the new government passed a vote of confidence and was ratified by the Congolese Chamber and Senate.

Independence Day was celebrated on 30 June in a ceremony attended by many dignitaries including King Baudouin and the foreign press, Patrice Lumumba delivered his famous independence speech[1] after being officially excluded from the event programme, despite being the elected Congolese Prime Minister. In direct contrast to the paternalistic glorification of colonialism in the speech of King Baudouin, as well as the relatively harmless speech of President Kasa-Vubu, Lumumba's outspoken anti-colonial speech resonated with the crowd for its emotional appeal while simultaneously humiliating and alienating the King and his entourage.[2][3] Lumumba was later harshly criticised for the inappropriate nature of this speech.[4]

[edit] Actions as Prime Minister

A few days after gaining its independence, Lumumba made the fateful decision to raise the pay of all government employees except for the army. Late on 5 July, this sparked a mutiny among soldiers (who were also rebelling against their officers who were mostly Belgians) at the Thysville military base. It quickly spread throughout the country, leading to a general breakdown in law and order. Lumumba was unable to regain control. Soon the country was overrun by gangs of soldiers and looters, causing a media sensation, particularly over Europeans fleeing the country.[5]

The province of Katanga declared independence under regional premier Moïse Tshombe on 11 July 1960 with support from the Belgian government and mining companies such as Union Minière.[6] Despite the arrival of United Nations troops, unrest continued. Lumumba sought Soviet aid to forcefully subdue Katanga. Soviet troops were then used in an invasion, which failed due to poor intelligence and poor knowledge of local conditions. Lumumba now lost the support of his colleagues and President Kasa-Vubu.[7]

[edit] Deposed and arrested

In September, the President dismissed Lumumba from government. In retaliation, Lumumba illegally declared Kasa-Vubu deposed and won a vote of confidence in the Senate, while the newly appointed prime minister failed to gain parliament's confidence. On 14 September, a coup d’état organized by Colonel Joseph Mobutu and endorsed by the CIA incapacitated both Lumumba and Kasa-Vubu.[5] Lumumba was placed under house arrest at the prime minister's residence, although UN troops were positioned around the house to protect him. Nevertheless, Lumumba decided to rouse his supporters in Haut-Congo. Smuggled out of his residence at night, he escaped to Stanleyville, where he attempted to set up his own government and army.[8] Pursued by troops loyal to Mobutu he was finally captured in Port Francqui and arrested on 1 December 1960 and flown to Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) in handcuffs. He desperately appealed to local UN troops to save him, but he was no longer their responsibility. Mobutu said Lumumba would be tried for inciting the army to rebellion and other crimes. United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld made an appeal to Kasa-Vubu asking that Lumumba be treated according to due process of law. The USSR denounced Hammarskjöld and the Western powers as responsible for Lumumba's arrest and demanded his release.

The UN Security Council was called into session on 7 December 1960 to consider Soviet demands that the UN seek Lumumba's immediate release, the immediate restoration of Lumumba as head of the Congo government, the disarming of the forces of Mobutu, and the immediate evacuation of Belgians from the Congo. Hammarskjöld, answering Soviet attacks against his Congo operations, said that if the UN forces were withdrawn from the Congo "I fear everything will crumble."

The threat to the UN cause was intensified by the announcement of the withdrawal of their contingents by Yugoslavia, the United Arab Republic, Ceylon, Indonesia, Morocco, and Guinea. The Soviet pro-Lumumba resolution was defeated on 14 December 1960 by a vote of 8-2. On the same day, a Western resolution that would have given Hammarskjöld increased powers to deal with the Congo situation (and perhaps intervene on Lumumba's behalf) was vetoed by the Soviet Union.

Lumumba was sent first on 3 December, to Thysville military barracks Camp Hardy, 150 km (about 100 miles) from Leopoldville. However, when security and disciplinary breaches threatened Lumamba's safety, it was decided that he should be transferred to the Katanga Province.

[edit] Death

Lumumba was forcibly restrained on the flight to Elizabethville (now Lubumbashi) on 17 January 1961 after attempting to incite the other passengers.[9] On arrival, he was conducted under arrest to Brouwez House and held there bound and gagged while President Tshombe and his cabinet decided what to do with him.

Later that night, Lumumba was driven to an isolated spot where three firing squads had been assembled. According to David Akerman and Ludo de Witte (2002:97-152), the firing squads were commanded by a Belgian, Captain Julien Gat, and another Belgian, Police Commissioner Verscheure, had overall command of the execution site.[10] The Belgian Commission has found that the execution was carried out by Katanga's authorities, but de Witte found written orders from the Belgian government requesting Lumumba's murder and documents on various arrangements, such as death squads. It reported that President Tshombe and two other ministers were present with four Belgian officers under the command of Katangan authorities. Lumumba and two other comrades from the government, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, were lined up against a tree and shot one at a time. The execution most likely took place on 17 January 1961 between 9:40PM and 9:43PM according to the Belgian report. Lumumba's corpse was buried nearby.

No statement was released until three weeks later despite rumours that Lumumba was dead. His death was formally announced on Katangese radio when it was alleged that he escaped and was killed by enraged villagers. On January 18, panicked by rumours indicating that the burial of the three bodies had been observed, members of the murder team went to dig up the bodies and move them to a place near the border with Rhodesia for reburial. Belgian Police Commissioner Gerard Soete later admitted in several accounts that he and his brother led the first and a second second exhumation. Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure also took part. On the afternoon and evening of January 21, Commissioner Soete and his brother dug up Lumumba's corpse for the second time, cut it up with a hacksaw, and dissolved it in concentrated sulfuric acid (de Witte 2002:140-143).[11] Only some teeth and a fragment of skull and bullets survived the process, kept as souvenirs. In an interview on Belgian television in a program on the assassination of Lumumba in 1999, Soete displayed a bullet and two teeth that he boasted he had saved from Lumumba's body.[11] De Witte also mentions that Verscheure kept souvenirs from the exhumation: bullets from the skull of Lumumba (de Witte 2002: 140).

After the announcement of Lumumba's death, street protests were organized in several European countries — in Belgrade, capital of Yugoslavia, protesters sacked the Belgian embassy and confronted the police, and in London a crowd marched from Trafalgar Square to the Belgian embassy, where a letter of protest was delivered and where protesters clashed with police.[12]

There is much speculation over any role that the Belgian and US governments played in the prime minister's murder. The Belgian Commission investigating Lumumba's assassination concluded that (1) Belgium wanted Lumumba arrested, (2) Belgium was not particularly concerned with Lumumba's physical well being, and (3) although informed of the danger to Lumumba's life, Belgium did not take any action to avert his death. But the report also specifically denied that Belgium ordered Lumumba's assassination (but see paragraph above) [13]

Under its own 'Good Samaritan' laws, Belgium was legally culpable for failing to prevent the assassination from taking place and was also in breach of its obligation (under U.N. Resolution 290 of 1949) to refrain from acts or threats "aimed at impairing the freedom, independence or integrity of another state."[14]

It was revealed that U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had said "something [to CIA chief Allen Dulles] to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated".[15] This was revealed by a declassified interview with then-US National Security Council minutekeeper Robert Johnson released in August 2000 from Senate intelligence committee's inquiry on covert action. The committee later found that while the CIA had conspired to kill Lumumba, it was not involved in the murder.[15] In 1975, the Church Committee went on record with the finding that Allen Dulles had ordered Lumumba's assassination as "an urgent and prime objective". (Dulles' own words).[16] Furthermore, de-classified CIA cables quoted or mentioned in the Church report and in Kalb (1972) mention two specific CIA plots to murder Lumumba: the poison plot and a shooting plot. Although some sources claim that CIA plots ended when Lumumba was captured, that is not stated or shown in the CIA records. Rather, those records show two still-partly-censored CIA cables from Elizabethville on days significant in the murder: January 17, the day Lumumba died, and January 18, the day of the first exhumation. The cable on the 17, after a long censored section, talks about where they need to go from there. On the 18th, the cable expresses thanks for Lumumba being sent to them and then says that, had Elizabethville base known he was coming, they would have "baked a snake". (see [17]) Significantly, David Doyle, the then chief of base, Elizabethville, told other CIA officers later that he had had Lumumba's body in the trunk of his car to try to find a way to dispose of it.[18] The cable in question has now been further declassified. It states that the writer's sources (not yet declassified) said that after being taken from the airport Lumumba was imprisoned by "all white guards" (CIA document #CO 1366116). Despite knowing that Lumumba was killed while in the hands of Whites, CIA administrators always attributed the murder to Congolese.

[edit] Plots by U.S. and Belgium

The report of 2001 by the Belgian Commission mentions that there had been previous U.S. and Belgian plots to kill Lumumba. Among them was a Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored attempt to poison him, which may have come on orders from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[19] CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb was a key person in this by devising a poison resembling toothpaste.[20][21][22][23] However, the plan is said to have failed because the local CIA Station Chief, Larry Devlin, had a conscience issue and did not go forward.[21][22][24]However, as Kalb points out in her book, Congo Cables, the record shows that many communications by Devlin at the time urged elimination of Lumumba (p. 53, 101, 129-133, 149-152, 158-159, 184-185, 195). Also, the CIA helped to capture Lumumba for his transfer to his enemies in Katanga, and the CIA administrator in then Elizabethville was in direct touch with the killers the night Lumumba was killed. Furthermore, a CIA agent had the body in the trunk of his car (p. 105, Stockwell, John 1978 In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story), Stockwell, who knew Devlin well felt Devlin knew more than anyone else about the murder (71-72, 136-137).

In February 2002, the Belgian government apologised to the Congolese people, and admitted to a "moral responsibility" and "an irrefutable portion of responsibility in the events that led to the death of Lumumba." In July, documents released by the United States government revealed that while the CIA had been kept informed of Belgium's plans, it had no direct role in Lumumba's eventual death.[21]

This same disclosure showed that U.S. perception at the time was that Lumumba was a communist.[25] Eisenhower's reported call, at a meeting of his national security advisers, for Lumumba's elimination must have been brought on by this perception. Both Belgium and the US were clearly influenced in their unfavourable stance towards Lumumba by the Cold War. He seemed to gravitate around the Soviet Union, although it was the only place he could find support in his country's effort to rid itself of colonial rule, not because he was a communist.[26] The US was the first country Lumumba requested help from.[27] Lumumba, for his part, not only denied being a Communist, but said he found colonialism and Communism to be equally deplorable, and professed his personal preference for neutrality between the East and West.[28]

[edit] Legacy

| This section may be inaccurate or unbalanced in favor of certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. (March 2009) |

[edit] Political

The reasons that Lumumba provoked such intense emotion are not immediately evident. His viewpoint was not exceptional. He was for a unitary Congo and against division of the country along ethnic or regional lines. Like many other African leaders, he supported pan-Africanism and the liberation of colonial territories. He proclaimed his regime one of “positive neutralism,” which he defined as a return to African values and rejection of any imported ideology, including that of the Soviet Union.

Lumumba was, however, a man of strong character who intended to pursue his policies, regardless of the enemies he made within his country or abroad. The Congo, furthermore, was a key area in terms of the geopolitics of Africa, and because of its wealth, size, and proximity to white-dominated southern Africa, Lumumba’s opponents had reason to fear the consequences of a radical or radicalized Congo regime. Moreover, in the context of the Cold War, the Soviet Union’s support for Lumumba appeared at the time as a threat to many in the West.[29]

Lumumba bequeathed very few positive results from his term of office. He failed to promote development and alienated his colleagues and supporters alike. In addition he failed to stave off or quell a civil war that erupted within days of his appointment as prime minister. Instead he behaved impetuously and followed expedients rather than policies that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people, including himself.[30]

[edit] 2006 Congolese elections

Nevertheless, the image of Patrice Lumumba continues to serve as an inspiration in contemporary Congolese politics. In the 2006 elections, several parties claimed to be motivated by his ideas,including the People's Party for Reconstruction and Democracy (PPRD), the political party initiated by the incumbent President Joseph Kabila.[31] Antoine Gizenga, who served as Lumumba's Deputy Prime Minister in the post-independence period, was a 2006 Presidential candidate under the Unified Lumumbist Party (Parti Lumumbiste Unifié (PALU))[32] and was named prime minister at the end of the year. Other political parties that directly utilise his name include the Mouvement National Congolais-Lumumba (MNC-L) and the Mouvement Lumumbiste (MLP).

[edit] Family and politics

Patrice Lumumba's family is actively involved in contemporary Congolese politics. Patrice Lumumba was married and had five children; François was the eldest followed by Patrice junior, Julienne, Roland and Guy-Patrice Lumumba. François Lumumba was 10 years old when Patrice died. Before his imprisonment, Patrice arranged for his wife and children to move into exile in Egypt, where François spent his childhood, then went to Hungary for education (he holds a doctorate in political economics). He returned to Congo in 1992 to oppose Mobutu since which time he has been the leader of the Mouvement National Congolais Lumumba (MNC-L), his father's original political party.[33]

Lumumba's youngest son, Patrice-Guy, born six months after his father's death, was an independent presidential candidate in the 2006 elections,[34] but received less than 1% of the vote.

On the DVD of the film Lumumba, the special features section includes an interview with Julienne in which she speaks of how her father knew that he was going to die for the cause, that he spoke of it frequently but did not anticipate the rule of Mobutu. She says that Lumumba had faith that his message would live on after his death.

[edit] Writings by Lumumba

- Congo, My Country, 1962, New York: Praeger (Books That Matter)

- Lumumba Speaks: The Speeches and Writings of Patrice Lumumba, 1958-1961 (Collection of Speeches, Little, Brown and Company, 1972) Translated by Helen R. Lane. Ed. Jean Van Lierde

[edit] Writings about Lumumba

- Aimé Césaire, Une Saison au Congo (1966); Eng. trans. by Ralph Manheim, A Season in the Congo (1969). A poetic drama about the career and death of Lumumba.

- W. A. E Skurnik, African Political Thought: Lumumba, Nkrumah, Touré (Social Science Foundation and Graduate School of International Studies, University of Denver. Monograph series in world affairs, v. 5, no. 3-4), 1968, Denver: University of Denver, ASIN B0006CNYSW

- Ludo De Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, Trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (Orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-410-3

- Thomas R. Kanza, Conflict in the Congo: The Rise and Fall of Lumumba (Penguin African library), 1972, New York: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-041030-9

- Robin McKown, Lumumba: A Biography, 1969, London: Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-07776-9

- G. Heinz, Lumumba: The Last Fifty Days, 1980, New York: Grove Press, ASIN B0006C07TQ

- Panaf, Patrice Lumumba (Panaf Great Lives), 1973, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-901787-31-0

- Kwame Nkrumah, Challenge of the Congo, 1967, New York: International Publishers

[edit] Tributes

- In 1966 Patrice Lumumba's image was rehabilitated by the Mobutu regime and he was proclaimed a national hero and martyr in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. By a presidential decree, the Brouwez House, site of Lumumba's brutal torture on the night of his murder, became a place of pilgrimage in the Congo.[35] Plans made to erect a spire in Lumumba's memory did not proceed but the anniversary of Lumumba's death was commemorated yearly until 1974, upon the unveiling of Mobutism.

- A major transportation artery in Kinshasa, the Lumumba Boulevard, is named in his honour. The boulevard goes past an interchange with a giant tower, the Tour de l'Echangeur (the main landmark of Kinshasa) commemorating him. On the tower's plaza, the first Kabila regime erected a tall statue of Lumumba with a raised hand, greeting people coming from Kinshasa International Airport.

- In Bamako, Mali, Lumumba Square is a large central plaza with a life-size statue of Lumumba, a park with fountains, and a flag display. Around Lumumba Square are various businesses, embassies and Bamako's largest bank.

- Streets were also named after him in Haiti, Tanzania, Ghana, Budapest, Hungary (between 1961 and 1990); Jakarta (between 1945 to 1967); Belgrade, Serbia; Bata and Malabo, Equatorial Guinea; Tehran, Iran; Algiers, Algeria (Rue Patrice Lumumba);[36] Santiago de Cuba, Cuba (since 1960, formerly Avenida de Bélgica); Łódź, Poland; Kiev, Ukraine; Rabat, Morocco; Maputo, Mozambique; Leipzig, Germany; Lusaka, Zambia ("Lumumba Street").

- The Peoples' Friendship University of the USSR was renamed "Patrice Lumumba Peoples' Friendship University" in 1961, but it was later renamed "The Peoples' Friendship University of Russia" in the post-Soviet landscape in 1992.[37]

- In Belgrade, Serbia, "The Patris Lumumba Hall of Residence" at Belgrade University was built in 1961 and continues to carry Lumumba's name.[38]

- In Kampala, Uganda, "Lumumba Hall" of Residence at Makerere University continues to carry his name.

- "Lumumba" is a popular choice for children's names throughout Africa.[39]

- American stand-up comedian Patrice Oneal is named after Lumumba.

- Argentinian Reggae Band, was named "Lumumba".

- In 1964 Malcolm X labelled Patrice Lumumba, "the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent".

- In 1969 students from the Black Student Council and Mexican-American Youth Association of the University of California, San Diego formed Lumumba-Zapata College, now known as Thurgood Marshall College.

- A student's hostel in Belgrade, Serbia is called Patrice Lumamba in his honour.

- A student's Hall in Makerere University, Uganda is called Lumumba Hall in the honor of Patrice Lumumba.

- In Viennese coffee houses, Lumumba is a cocoa with rum, Lumumba Coffee a black coffee with rum and whipped cream. Both beverages originate from northern Germany, where they are called Tote Tante (dead aunt, with cocoa) and Pharisäer (pharisee, with coffee; see Nordstrand, Germany) respectively.[40][41]

[edit] Filmography

- Lumumba: Death of a Prophet (1992). Documentary distributed by California Newsreel.

- Lumumba : Un crime d'Etat (in English Lumumba: A state crime)

- Congo 1961, El at the Internet Movie Database. As himself in a documentary.

[edit] Archive video and audio

- BBC On This Day - 14 September, 1960: Violence Follows Army Coup in Congo

- BBC On This Day - 13 February, 1961: EX-Congo PM Declared Dead

- BBC On This Day - 19 February, 1961: Lumumba Rally Clashes with UK Police

[edit] In popular culture

[edit] Books

- Tim Butcher: Blood River - A Journey To Africa's Broken Heart, 2007. ISBN 0-701-17981-3

- Bogumil Jewsiewicki, ed., A Congo Chronicle: Patrice Lumumba in Urban Art, 1999, New York: Museum for African Art, ISBN 0-945802-25-0. The catalogue of a travelling exhibition of contemporary Congolese artists who were inspired by the legacy of Lumumba.

- Barbara Kingsolver's The Poisonwood Bible is a fictional account of an American missionary family in the Congo during the election and assassination of Lumumba. The book is critical of western governments and their interference in Africa.

- Godfrey Mwakikagile, Nyerere and Africa: End of an Era, Third Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, "Chapter Six: Congo in The Sixties: The Bleeding Heart of Africa," pp. 147 - 205, ISBN 978-0980253412; Godfrey Mwakikagile, Africa and America in The Sixties: A Decade That Changed The Nation and The Destiny of A Continent, First Edition, New Africa Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0980253429.

[edit] Films

- Seduto alla sua destra (1968). A fictional film by writer-director Valerio Zurlini starring Woody Strode as a thinly-disguised Lumumba. (Released in the U.S. as Black Jesus.)

- JFK at the Internet Movie Database (uncredited) Himself (archive footage)

- Lumumba (film) (2000). Dramatized biography of Lumumba directed by Raoul Peck.

- Tule tagasi, Lumumba at the Internet Movie Database aka Come Back, Lumumba. Estonian film from 1992.

- In the film The Day of the Jackal, it is portrayed that the Jackal is the same assassin who killed Patrice Lumumba and Rafael Leónidas Trujillo and before attempting to murder Charles de Gaulle.

- In the episode, The Gladiators, in the TV serial "The New Avengers", the terrorists were said to have trained at the Patrice Lumumba University.

- In the episode, Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man, in the TV series, "The X-files", it is suggested that the Cigarette Smoking Man assassinated Patrice Lumumba.

- In the film "Claudine," when the male lead "Roop" first hears Claudine's daughter's name is "Patrice," he asks, "Like Patrice Lumumba?" She replies, "No. Like Patrice Price."

[edit] References

- ^ "Independence Day Speech". Africa Within. http://www.africawithin.com/lumumba/independence_speech.htm. Retrieved on 15 July 2006.

- ^ Ludo De Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, Trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (Orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-410-3, pp. 1-3.

- ^ "Marred: Lumumba's offensive speech in King's presence". Guardian Unlimited. http://www.guardian.co.uk/congo/story/0,,766933,00.html. Retrieved on 14 August 2006.

- ^ A History of the Modern World, Johnson P, Weidenfeld, London ,(1991)

- ^ a b Larry Devlin, Chief of Station Congo, 2007, Public Affairs, ISBN 1-58648-405-2

- ^ Osabu-Kle, Daniel Tetteh (2000). Compatible Cultural Democracy. Broadview Press. pp. 254. ISBN 1551112892.

- ^ Johnson. P, ibid

- ^ Longman History of Africa, Snellgrove L. and Greenberg K., Longman, London (1973)

- ^ "Correspondent:Who Killed Lumumba-Transcript". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/audio_video/programmes/correspondent/transcripts/974745.txt. 00.35.38-00.35.49

- ^ "Correspondent:Who Killed Lumumba-Transcript". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/english/static/audio_video/programmes/correspondent/transcripts/974745.txt. 00.36.57

- ^ a b Patrice Lumumba - Mysteries of History - U.S. News Online

- ^ BBC: "1961: Lumumba rally clashes with UK police"

- ^ Report Reproves Belgium in Lumumba's Death - New York Times

- ^ Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan; Mango, Anthony (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and international agreements. Taylor & Francis. p. 2571. ISBN 0415939240.

- ^ a b Guardian Unlimited | Archive Search

- ^ William Blum Killing Hope, p. 158, MBI Publishing Co., 2007 ISBN 978-0760324578

- ^ FOIA declassified documents on Lumumba on the CIA website

- ^ (one example of those: John Stockwell In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story. W.W. Norton, 1978: 105).

- ^ "President 'ordered murder' of Congo leader". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/Archive/Article/0,4273,4049783,00.html. Retrieved on 18 June 2006.

- ^ 6) Plan to poison Congo leader Patrice Lumumba (p. 464), Family jewels CIA documents, on the National Security Archive's website

- ^ a b c "A killing in Congo". US News. http://www.usnews.com/usnews/doubleissue/mysteries/patrice.htm. Retrieved on 18 June 2006.

- ^ a b ""Who killed Lumumba"". "Africa Within". http://www.africawithin.com/lumumba/who_killed_lumumba.htm.

- ^ Sidney Gottlieb "obituary" "Sidney Gottlieb". Counterpunch.org. http://www.counterpunch.org/gottlieb.html.

- ^ "Interview with Mark Garsin". Counterpunch.org. http://www.counterpunch.org/mazur01292005.html.

- ^ Blaine Harden, Africa: Dispatches from a Fragile Continent, p. 50

- ^ Sean Kelly, America's Tyrant: The CIA and Mobutu of Zaire, p. 29

- ^ Kelly, p. 28

- ^ Kelly, p. 49

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Johnson, P. ibid. pp515-17

- ^ "Kabila Party formed in DR Congo". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/1907252.stm. Retrieved on 30 July 2006.

- ^ "Profile: Congo opposition candidates". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/africa/5199518.stm. Retrieved on 30 July 2006.

- ^ "Interview with François Lumumba by André Soussan". African Geopolitics. http://www.african-geopolitics.org/show.aspx?ArticleId=3100. Retrieved on 30 July 2006.

- ^ "Key Figures in Congo's Electoral Process". United Nations Integrated Regional Information Networks. http://www.irinnews.org/print.asp?ReportID=54275. Retrieved on 30 July 2006.

- ^ Ludo De Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, Trans. by Ann Wright and Renée Fenby, 2002 (Orig. 2001), London; New York: Verso, ISBN 1-85984-410-3, pp. 165.

- ^ BBC News | AFRICA | More killings in Algeria

- ^ CNN - From Marxism 101 to Capitalism 101 - 26 July 1997

- ^ http://www.sc.org.yu/dom.php?dom=patris

- ^ BBC NEWS | World | Africa | Naming children for a head start in Africa

- ^ Tote Tante (Heiße Tante) Lumumba ein Kakao-Getränk - Pharisäer Kaffee mit Rum

- ^ Cocktail-Rezept: Lumumba

[edit] External links

- Virtual Memorial to Patrice Lumumba at Find-A-grave

- SpyCast - 1 December 2007: On Assignment to Congo - Peter chats with Larry Devlin, the CIA’s legendary station chief in Congo during the 1960s. Larry reflects on his reasons for joining the CIA, the political situation in Congo at the time, and the face-off with the Soviets in the Third World. He also discusses his response to the controversial directive from headquarters to have Congo’s Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba killed.

- Africa Within A rich source of information on Lumumba, including a reprint of Stephen R. Weissman's 21 July 2002 article from the Washington Post, "Opening the Secret Files on Lumumba's Murder," detailing declassified documents on the CIA's role in Lumumba's murder and the overthrow by Mobutu.

- BBC Lumumba apology: Congo's mixed feelings

- Mysteries of History Lumumba assassination

- Lumumba and the Congo Documentary of Lumumba's life and work in the Congo

- BBC An "On this day" text. It features an audio clip of a BBC correspondent on Lumumba's death.

- Belgian Parliament The findings of the Belgian Commission of 2001 investigating Belgian involvement in the death of Lumumba. Documents at the bottom of the page are in English.

- Belgian Commission's Conclusion A particular document from the previous link

- D'Lynn Waldron Dr. D'Lynn Waldron's extensive archive of articles, photographs, and documents from her days as a foreign press correspondent in Lumumba's 1960 Congo

- Mysteries of History Lumumba assassination

- CIA plans included the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, report from the Washington Post by Karen DeYoung and Walter Pincus

- David Akerman (2000-10-21). "Who Killed Lumumba?". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/correspondent/974745.stm. Retrieved on 2007-12-01.

- Harry Gilroy (1960-07-01). "Lumumba Assails Colonialism as Congo Is Freed". New York Times. http://partners.nytimes.com/library/world/africa/600701lumumba.html. Retrieved on 2007-12-01.

- "The Bad Dream". Time Magazine. 1961-01-20. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,871970,00.html. Retrieved on 2007-12-01.

| Preceded by Position created on independence from Belgium |

Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo 24 June 1960 - 5 September 1960 |

Succeeded by Joseph Ileo |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||