Prime number theorem

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In number theory, the prime number theorem (PNT) describes the asymptotic distribution of the prime numbers. The prime number theorem gives a rough description of how the primes are distributed.

Roughly speaking, the prime number theorem states that if you randomly select a number nearby some large number N, the chance of it being prime is about 1 / ln(N), where ln(N) denotes the natural logarithm of N. For example, near N = 10,000, about one in nine numbers is prime, whereas near N = 1,000,000,000, only one in every 21 numbers is prime. In other words, the average gap between prime numbers near N is roughly ln(N).[1]

[edit] Statement of the theorem

Let π(x) be the prime-counting function that gives the number of primes less than or equal to x, for any real number x. For example, π(10) = 4 because there are four prime numbers (2, 3, 5 and 7) less than or equal to 10. The prime number theorem then states that the limit of the quotient of the two functions π(x) and x / ln(x) as x approaches infinity is 1, which is expressed by the formula

known as the asymptotic law of distribution of prime numbers. Using asymptotic notation this result can be restated as

This notation (and the theorem) does not say anything about the limit of the difference of the two functions as x approaches infinity. (Indeed, the behavior of this difference is very complicated and related to the Riemann hypothesis.) Instead, the theorem states that x/ln(x) approximates π(x) in the sense that the relative error of this approximation approaches 0 as x approaches infinity.

The prime number theorem is equivalent to the statement that the nth prime number pn is approximately equal to n ln(n), again with the relative error of this approximation approaching 0 as n approaches infinity.

[edit] History of the asymptotic law of distribution of prime numbers and its proof

Based on the tables by Anton Felkel and Jurij Vega, Adrien-Marie Legendre conjectured in 1796 that π(x) is approximated by the function x/(ln(x)-B), where B=1.08... is a constant close to 1. Carl Friedrich Gauss considered the same question and, based on the computational evidence available to him and on some heuristic reasoning, he came up with his own approximating function, the logarithmic integral li(x), although he did not publish his results. Both Legendre's and Gauss's formulas imply the same conjectured asymptotic equivalence of π(x) and x / ln(x) stated above, although it turned out that Gauss's approximation is considerably better if one considers the differences instead of quotients.

In two papers from 1848 and 1850, the Russian mathematician Pafnuty L'vovich Chebyshev attempted to prove the asymptotic law of distribution of prime numbers. His work is notable for the use of the zeta function ζ(s) predating Riemann's celebrated memoir of 1859, and he succeeded in proving a slightly weaker form of the asymptotic law, namely, that if the limit of π(x)/(x/ln(x)) as x goes to infinity exists at all, then it is necessarily equal to one. He was able to prove unconditionally that this ratio is bounded above and below by two explicitly given constants near to 1 for all x. Although Chebyshev's paper did not quite prove the Prime Number Theorem, he used his estimates for π(x) to prove Bertrand's postulate that there exists a prime number between n and 2n for any integer n ≥ 2.

Without doubt, the single most significant paper concerning the distribution of prime numbers was Riemann's 1859 memoir On the Number of Primes Less Than a Given Magnitude, the only paper he ever wrote on the subject. Riemann introduced revolutionary ideas into the subject, the chief of them being that the distribution of prime numbers is intimately connected with the zeros of the analytically extended Riemann zeta function of a complex variable. In particular, it is in this paper of Riemann that the idea to apply methods of complex analysis to the study of the real function π(x) originates. Extending these deep ideas of Riemann, two proofs of the asymptotic law of the distribution of prime numbers were obtained independently by Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin and appeared in the same year (1896). Both proofs used methods from complex analysis, establishing as a main step of the proof that the Riemann zeta function ζ(s) is non-zero for all complex values of the variable s that have the form s = 1 + it with t > 0.[2]

During the 20th century, the theorem of Hadamard and de la Vallée-Poussin also became known as the Prime Number Theorem. Several different proofs of it were found, including the "elementary" proofs of Atle Selberg and Paul Erdős (1949).

[edit] A very rough proof sketch

In a lecture on prime numbers for a general audience, Fields medalist Terence Tao described one approach to proving the prime number theorem in poetic terms: listening to the "music" of the primes. We start with a "sound wave" that is "noisy" at the prime numbers and silent at other numbers; this is the von Mangoldt function. Then we analyze its notes or frequencies by subjecting it to a process akin to Fourier transform; this is the Mellin transform. Then we prove, and this is the hard part, that certain "notes" cannot occur in this music. This exclusion of certain notes leads to the statement of the prime number theorem. According to Tao, this proof yields much deeper insights into the distribution of the primes than the "elementary" proofs discussed below.[3]

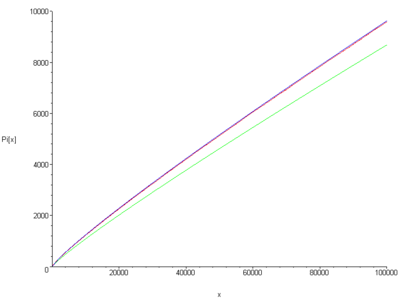

[edit] The prime-counting function in terms of the logarithmic integral

Carl Friedrich Gauss conjectured that an even better approximation to π(x) is given by the offset logarithmic integral function Li(x), defined by

Indeed, this integral is strongly suggestive of the notion that the 'density' of primes around t should be 1/lnt. This function is related to the logarithm by the asymptotic expansion

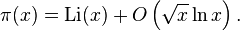

So, the prime number theorem can also be written as π(x) ~ Li(x). In fact, it follows from the proof of Hadamard and de la Vallée Poussin that

for some positive constant a, where O(…) is the big O notation. This has been improved to

Because of the connection between the Riemann zeta function and π(x), the Riemann hypothesis has considerable importance in number theory: if established, it would yield a far better estimate of the error involved in the prime number theorem than is available today. More specifically, Helge von Koch showed in 1901[4] that, if and only if the Riemann hypothesis is true, the error term in the above relation can be improved to

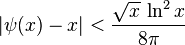

The constant involved in the big O notation was estimated in 1976 by Lowell Schoenfeld:[5] assuming the Riemann hypothesis,

for all x ≥ 2657. He also derived a similar bound for the Chebyshev prime-counting function ψ:

for all x ≥ 73.2.

The logarithmic integral Li(x) is larger than π(x) for "small" values of x. This is because it is (in some sense) counting not primes, but prime powers, where a power pn of a prime p is counted as 1/n of a prime. This suggests that Li(x) should usually be larger than π(x) by roughly Li(x1/2)/2, and in particular should usually be larger than π(x). However, in 1914, J. E. Littlewood proved that this is not always the case. The first value of x where π(x) exceeds Li(x) is probably around x = 10316; see the article on Skewes' number for more details.

[edit] Elementary proofs

In the first half of the twentieth century, some mathematicians felt that there exists a hierarchy of techniques in mathematics, and that the prime number theorem is a "deep" theorem, whose proof requires complex analysis. Methods with only real variables were supposed to be inadequate. G. H. Hardy was one notable member of this group.[6]

The formulation of this belief was somewhat shaken by a proof of the prime number theorem based on Wiener's tauberian theorem, though this could be circumvented by awarding Wiener's theorem "depth" itself equivalent to the complex methods. The notion of "elementary proof" in number theory is not usually defined precisely, but it usually seems to correspond roughly to proofs that can be carried out in Peano arithmetic, rather than more powerful theories, such as second order arithmetic. There are statements of Peano arithmetic that can be proved in second order arithmetic but not first order arithmetic (see the Paris-Harrington theorem for an example), but they seem in practice to be rare. However, Atle Selberg found an elementary proof of the prime number theorem in 1949, which uses only number-theoretic means. (Paul Erdős used Selberg's ideas to produce a slightly different elementary proof at about the same time.) Selberg's work effectively laid rest to the whole concept of "depth" for the prime number theorem, showing that technically "elementary" methods (in other words Peano arithmetic) were sharper than previously expected. In 2001 Sudac showed that the prime number theorem can even be proved in primitive recursive arithmetic[7], a much weaker theory than Peano arithmetic.

Avigad et al. wrote a computer verified version of Selberg's elementary proof in the Isabelle theorem prover in 2005.[8]

Dorian Goldfeld wrote a paper[6] detailing the history of the elementary proof, including a study of the Erdős–Selberg priority dispute over who first gave an elementary proof.

[edit] The prime number theorem for arithmetic progressions

Let πn,a(x) denote the number of primes in the arithmetic progression a, a + n, a + 2n, a + 3n, … less than x. Dirichlet and Legendre conjectured, and Vallée Poussin proved, that, if a and n are coprime, then

where φ(·) is the Euler's totient function. In other words, the primes are distributed evenly among the residue classes [a] modulo n with gcd(a, n) = 1. This can be proved using similar methods used by Newman for his proof of the prime number theorem.[9]

Although we have in particular

empirically the primes congruent to 3 are more numerous and are nearly always ahead in this "prime number race"; the first reversal occurs at x = 26,861. [10] However Littlewood showed in 1914 [10] that there are infinitely many sign changes for the function

so the lead in the race switches back and forth infinitely many times. The prime number race generalizes to other moduli and is the subject of much research; Granville and Martin give a very thorough exposition and survey. [10]

[edit] Bounds on the prime-counting function

The prime number theorem is an asymptotic result. Hence, it cannot be used to bound π(x).

However, some bounds on π(x) are known, for instance Pierre Dusart's

The first inequality holds for all x ≥ 599 and the second one for x ≥ 355991[11].

A weaker but sometimes useful bound is

for x ≥ 55[12]. In Dusart's thesis you also find slightly stronger versions of this type of inequality (valid for larger x.)

[edit] Approximations for the nth prime number

As a consequence of the prime number theorem, one gets an asymptotic expression for the nth prime number, denoted by pn:

A better approximation is

Rosser's theorem states that pn is larger than n ln n. This can be improved by the following pair of bounds[14]:

The left inequality is due to Pierre Dusart[15] and is valid for n ≥ 2.

[edit] Table of π(x), x / ln x, and li(x)

The table compares exact values of π(x) to the two approximations x / ln x and li(x). The last column, x / π(x), is the average prime gap below x.

-

x π(x)[16] π(x) − x / ln x[17] π(x) / (x / ln x) li(x) − π(x)[18] x / π(x) 10 4 −0.3 0.921 2.2 2.500 102 25 3.3 1.151 5.1 4.000 103 168 23 1.161 10 5.952 104 1,229 143 1.132 17 8.137 105 9,592 906 1.104 38 10.425 106 78,498 6,116 1.084 130 12.740 107 664,579 44,158 1.071 339 15.047 108 5,761,455 332,774 1.061 754 17.357 109 50,847,534 2,592,592 1.054 1,701 19.667 1010 455,052,511 20,758,029 1.048 3,104 21.975 1011 4,118,054,813 169,923,159 1.043 11,588 24.283 1012 37,607,912,018 1,416,705,193 1.039 38,263 26.590 1013 346,065,536,839 11,992,858,452 1.034 108,971 28.896 1014 3,204,941,750,802 102,838,308,636 1.033 314,890 31.202 1015 29,844,570,422,669 891,604,962,452 1.031 1,052,619 33.507 1016 279,238,341,033,925 7,804,289,844,393 1.029 3,214,632 35.812 1017 2,623,557,157,654,233 68,883,734,693,281 1.027 7,956,589 38.116 1018 24,739,954,287,740,860 612,483,070,893,536 1.025 21,949,555 40.420 1019 234,057,667,276,344,607 5,481,624,169,369,960 1.024 99,877,775 42.725 1020 2,220,819,602,560,918,840 49,347,193,044,659,701 1.023 222,744,644 45.028 1021 21,127,269,486,018,731,928 446,579,871,578,168,707 1.022 597,394,254 47.332 1022 201,467,286,689,315,906,290 4,060,704,006,019,620,994 1.021 1,932,355,208 49.636 1023 1,925,320,391,606,803,968,923 37,083,513,766,578,631,309 1.020 7,250,186,216 51.939

[edit] Analogue for irreducible polynomials over a finite field

There is an analogue of the prime number theorem that describes the "distribution" of irreducible polynomials over a finite field; the form it takes is strikingly similar to the case of the classical prime number theorem.

To state it precisely, let F = GF(q) be the finite field with q elements, for some fixed q, and let Nn be the number of monic irreducible polynomials over F whose degree is equal to n. That is, we are looking at polynomials with coefficients chosen from F, which cannot be written as products of polynomials of smaller degree. In this setting, these polynomials play the role of the prime numbers, since all other monic polynomials are built up of products of them. One can then prove that

If we make the substitution x = qn, then the right hand side is just

which makes the analogy clearer. Since there are precisely qn monic polynomials of degree n (including the reducible ones), this can be rephrased as follows: if you select a monic polynomial of degree n randomly, then the probability of it being irreducible is about 1/n.

One can even prove an analogue of the Riemann hypothesis, namely that

The proofs of these statements are far simpler than in the classical case. It involves a short combinatorial argument, summarised as follows. Every element of the degree n extension of F is a root of some irreducible polynomial whose degree d divides n; by counting these roots in two different ways one establishes that

where the sum is over all divisors d of n. Möbius inversion then yields

where μ(k) is the Möbius function. (This formula was known to Gauss.) The main term occurs for d = n, and it is not difficult to bound the remaining terms. The "Riemann hypothesis" statement depends on the fact that the largest proper divisor of n can be no larger than n/2.

[edit] See also

- Abstract analytic number theory for information about generalizations of the theorem.

- Landau prime ideal theorem for a generalization to prime ideals in algebraic number fields.

- Prime gap

- Twin prime conjecture

[edit] Notes

- ^ Hoffman, Paul (1998). The Man Who Loved Only Numbers. Hyperion. p. 227. ISBN 0-7868-8406-1.

- ^ Ingham, A.E. (1990). The Distribution of Prime Numbers. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–5. ISBN 0-521-39789-8.

- ^ Video and slides of Tao's lecture on primes, UCLA January 2007.

- ^ Helge von Koch (Dec 1901). "Sur la distribution des nombres premiers". Acta Mathematica 24 (1): 159–182. doi:.

- ^ Lowell Schoenfeld (Apr 1976). "Sharper Bounds for the Chebyshev Functions θ(x) and ψ(x), II". Mathematics of Computation 30 (134): 337–360.

- ^ a b D. Goldfeld The elementary proof of the prime number theorem: an historical perspective.

- ^ Olivier Sudac (Apr 2001). "The prime number theorem is PRA-provable". Theoretical Computer Science 257 (1–2): 185–239. doi:.

- ^ Jeremy Avigad, Kevin Donnelly, David Gray, Paul Raff (2005). "A formally verified proof of the prime number theorem". E-print cs. AI/0509025 in the ArXiv. http://arxiv.org/abs/cs.AI/0509025.

- ^ Ivan Soprounov (1998). A short proof of the Prime Number Theorem for arithmetic progressions. http://www.math.umass.edu/~isoprou/pdf/primes.pdf.

- ^ a b c Granville, Andrew; Greg Martin (January 2006). "Prime Number Races". American Mathematical Monthly (Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of American) 113 (1): 1–33. ISSN 0002-9890.

- ^ Pierre Dusart, Autour de la fonction qui compte le nombre de nombres premiers, doctoral thesis for l'Université de Limoges (1998).

- ^ Barkley Rosser (Jan 1941). "Explicit Bounds for Some Functions of Prime Numbers". American Journal of Mathematics 63 (1): 211–232. doi:.

- ^ Michele Cipolla (1902). "La determinazione assintotica dell'nimo numero primo". Matematiche Napoli 3: 132–166.

- ^ Eric Bach, Jeffrey Shallit (1996). Algorithmic Number Theory. 1. MIT Press. p. 233. ISBN 0-262-02405-5.

- ^ Pierre Dusart (1999). "The kth prime is greater than k(ln k + ln ln k-1) for k>=2". Mathematics of Computation 68: 411–415. http://www.ams.org/mcom/1999-68-225/S0025-5718-99-01037-6/S0025-5718-99-01037-6.pdf.

- ^ "Number of primes < 10^n (A006880)". On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://www.research.att.com/projects/OEIS?Anum=A006880.

- ^ "Difference between pi(10^n) and the integer nearest to 10^n / log(10^n) (A057835)". On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://www.research.att.com/projects/OEIS?Anum=A057835.

- ^ "Difference between Li(10^n) and Pi(10^n), where Li(x) = integral of log(x) and Pi(x) = number of primes <= x (A057752)". On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences. http://www.research.att.com/projects/OEIS?Anum=A057752.

[edit] References

- G.H. Hardy and J.E. Littlewood, "Contributions to the Theory of the Riemann Zeta-Function and the Theory of the Distribution of Primes", Acta Mathematica, 41(1916) pp.119-196.

- Andrew Granville, Harald Cramér and the distribution of prime numbers, Scandinavian Actuarial Journal, vol. 1, pages 12–28, 1995.

[edit] External links

- Table of Primes by Anton Felkel.

- Prime formulas and Prime number theorem at MathWorld.

- Prime number theorem on PlanetMath

- How Many Primes Are There? and The Gaps between Primes by Chris Caldwell, University of Tennessee at Martin.

- Tables of prime-counting functions by Tomás Oliveira e Silva