Three Mile Island accident

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Three Mile Island accident of 1979 was a partial core meltdown in Unit 2 (a pressurized water reactor manufactured by Babcock & Wilcox) of the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania near Harrisburg. It was the most significant accident in the history of the American commercial nuclear power generating industry, resulting in the release of up to 13 million curies of radioactive noble gases, but less than 20 curies of the particularly hazardous iodine-131.[1]

The accident began at 4:00 A.M. on Wednesday, March 28, 1979, with failures in the non-nuclear secondary system, followed by a stuck-open pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) in the primary system, which allowed large amounts of reactor coolant to escape. The mechanical failures were compounded by the initial failure of plant operators to recognize the situation as a loss of coolant accident due to inadequate training and ambiguous control room indicators. The scope and complexity of the accident became clear over the course of five days, as employees of Metropolitan Edison (Met Ed, the utility operating the plant), Pennsylvania state officials, and members of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) tried to understand the problem, communicate the situation to the press and local community, decide whether the accident required an emergency evacuation, and ultimately end the crisis.

In the end, the reactor was brought under control, although full details of the accident were not discovered until much later, following extensive investigations by both a presidential commission and the NRC. The "Kemeny Commission Report" concluded that "there will either be no case of cancer or the number of cases will be so small that it will never be possible to detect them. The same conclusion applies to the other possible health effects."[2] Several epidemiological studies in the years since the accident have supported the conclusion that radiation releases from the accident had no perceptible effect on cancer incidence in residents near the plant, though these findings have been contested by one team of researchers.[3]

Public reaction to the event was probably influenced by at least three factors: first, the release (12 days before the accident) of a popular movie called The China Syndrome, concerning an accident at a nuclear reactor;[4] second, what were felt to be confusing and conflicting communications from officials during the initial phases of the accident;[5] and last, many of the statements made by political and social activists long opposed to nuclear power.[citation needed] The accident was followed by essentially a complete cessation of the start of new nuclear plant construction in the US.

Contents |

[edit] Three Mile Island reactor accident

[edit] Understanding pressurized water reactors

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2008) |

| This article contains too much jargon and may need simplification or further explanation. Please discuss this issue on the talk page, and/or remove or explain jargon terms used in the article. Editing help is available. (March 2009) |

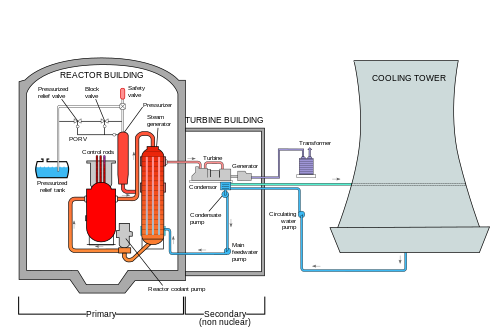

There are three major water/steam loops in most pressurized water reactors: the primary loop, the secondary loop, and the condenser feedwater (cooling tower) loop. The primary loop runs through the reactor. It consists of purified, demineralized water to which a small, variable amount of boron has been added for reactivity control. It is the primary thermal energy transport loop. The primary loop carries the thermal neutron fission heat energy from the fuel assemblies (the reactor's "core") to an area outside the reactor, where the energy can be more easily harnessed (via the secondary loop). The primary loop runs at a temperature far higher than the boiling point of water at standard atmospheric pressure, and must remain pressurized or the water will flash to steam, compromising cooling of the core. The water, which always remains in a liquid state, has two functions: to moderate or slow neutrons so they can be more easily captured by uranium fuel, and to transfer heat from the reactor.

In this reactor design, water is used as the primary loop transport medium because it is cheap, has a high thermal transport efficiency, and actually contributes to fission reaction safety. If this primary loop water is lost, neutron moderation will stop and self sustaining fission in the reactor core will be halted. This is, of course, not desirable under operating (or recently shutdown) conditions, since decay heat alone is sufficient to melt the fuel.

The secondary loop resembles the steam cycle in a conventional power plant. The feedwater pump moves cool water into the steam generator, a heat exchanger which uses heat from the primary loop to boil the water in the secondary loop. The resulting steam then spins a turbine that is connected to the electrical generator. Once its energy has been expended, the steam flows through a condenser, which is another type of heat exchanger that changes the steam back to feedwater and transfers the absorbed latent heat to the cooling tower water. The feedwater is then pumped back to the steam generator system and the process repeats.

The cooling tower loop provides cooling water for the condenser of the secondary loop and other plant operational cooling needs. After being heated by absorbing waste heat from the generation process, the water is cooled by flowing through the cooling tower, which in most cases is a natural draft water-to-air heat exchanger. Water lost to evaporation in the cooling tower is replenished by water from a nearby source.

[edit] Accident description

[edit] Stuck valve

In the nighttime hours preceding the accident, the TMI-2 reactor was running at 97 percent of full power, while the companion TMI-1 reactor was shut down for refueling.[7] The chain of events leading to the partial core meltdown began in TMI-2's secondary non-nuclear cooling system at 4:00 a.m. EST on March 28, 1979, when pumps in the condensate polishing system stopped running, followed immediately by the main feedwater pumps. This automatically triggered the turbine to shut down and the reactor to scram: control rods were inserted into the core and fission ceased. But the reactor continued to generate decay heat, and because water was no longer flowing through the secondary loop, the steam generators no longer removed that heat from the reactor.[8]

Once the primary feedwater pump system failed, three auxiliary pumps activated automatically. However, because the valves had been closed for routine maintenance, the system was unable to pump any water. The closure of these valves was a violation of a key NRC rule, according to which the reactor must be shut down if all auxiliary feed pumps are closed for maintenance. This failure was later singled out by NRC officials as a key one, without which the course of events would have been very different.[9] The pumps were activated manually eight minutes later, and manually deactivated between 1 and 2 hours later,[9] as per procedure, due to excessive vibration in the pumps.[10]

Due to the loss of heat removal from the primary loop and the failure of the auxiliary system to activate, the primary side pressure began to increase, triggering the pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) at the top of the pressurizer to open automatically. The PORV should have closed again when the excess pressure had been released and electric power to the solenoid of the pilot was automatically cut, but instead the main relief valve stuck open due to a mechanical fault. The open valve permitted coolant water to escape from the primary system, and was the principal mechanical cause of the crisis that followed.[11]

[edit] Confusion over valve status

A lamp in the control room, designed to light up when electric power was applied to the solenoid that operated the pilot valve of the PORV, went out, as intended, when the power was removed. This was incorrectly interpreted by the operators as meaning that the main relief valve was closed, when in reality it only indicated that power had been removed from the solenoid, not the actual position of the pilot valve or the main relief valve. Because this indicator was not designed to unambiguously indicate the actual position of the main relief valve, the operators did not correctly diagnose the problem for several hours.[12]

The design of the PORV indicator light was fundamentally flawed, because it implied that the PORV was shut when it went dark. When everything was operating correctly this was true, and the operators became habituated to rely on it. However, when things went wrong and the main relief valve stuck open, the dark lamp was actually misleading the operators by implying that the valve was shut. This caused the operators considerable confusion, because the pressure, temperature and levels in the primary circuit, so far as they could observe them via their instruments, were not behaving as they would have done if the PORV was shut — which they were convinced it was. This mental confusion contributed to the severity of the accident: because the operators were unable to break out a cycle of assumptions which conflicted with what their instruments were telling them, it was not until a fresh shift came in who did not have the mind-set of the first set of operators that the problem was correctly diagnosed. But by then, major damage had been done.

The operators had not been trained to understand the ambiguous nature of the PORV indicator and look for alternative confirmation that the main relief valve was closed. There was in fact a temperature indicator downstream of the PORV in the tail pipe between the PORV and the pressurizer that could have told them the valve was stuck open, by showing that the temperature in the tail pipe remained high after the PORV should have, and was assumed to have, shut. But this temperature indicator was not part of the "safety grade" suite of indicators designed to be used after an incident, and the operators had not been trained to use it. Its location on the back of the desk also meant that it was effectively out of sight of the operators.

[edit] Consequences of stuck valve

As the pressure in the primary system continued to decrease, steam pockets began to form in the reactor coolant, causing the pressurizer water level to rise even though coolant was being lost through the open PORV. Because of the lack of a dedicated instrument to measure the level of water in the core, operators judged the level of water in the core solely by the level in the pressurizer. Since it was high, they assumed that the core was properly covered with coolant, unaware that because of the voids forming in the reactor vessel, the indicator provided false readings.[13] This was a key contributor to the initial failure to recognize the accident as a loss of coolant accident, and led operators to turn off the emergency core cooling pumps, which had automatically started after the initial pressure decrease, due to fears the system was being overfilled.[14]

With the PORV still open, the quench tank that collected the discharge from the PORV overfilled, causing the containment building sump to fill and sound an alarm at 4:11 a.m. This alarm, along with higher than normal temperatures on the PORV discharge line and unusually high containment building temperatures and pressures, were clear indications that there was an ongoing loss of coolant accident, but these indications were initially ignored by operators.[15] At 4:15 a.m., the quench tank relief diaphragm ruptured, and radioactive coolant began to leak out into the general containment building. This radioactive coolant was pumped from the containment building sump to an auxiliary building, outside the main containment, until the sump pumps were stopped at 4:39 a.m.[16]

After almost 80 minutes of slow temperature rise, the primary loop pumps began to cavitate as steam, rather than water, began to pass through them. The pumps were shut down, and it was believed that natural circulation would continue the water movement. Steam in the system locked the primary loop, and as the water stopped circulating it was converted to steam in increasing amounts. About 130 minutes after the first malfunction, the top of the reactor core was exposed and the intense heat caused a reaction to occur between the steam forming in the reactor core and the zirconium nuclear fuel rod cladding. This fiery reaction burned off the nuclear fuel rod cladding, the hot plume of reacting steam and zirconium damaged the fuel pellets which released more radioactivity to the reactor coolant and produced hydrogen gas that is believed to have caused a small explosion in the containment building later that afternoon.[17]

At 6 a.m., there was a shift change in the control room. A new arrival noticed that the temperature in PORV tail pipe and the holding tanks was excessive and used a backup valve called a block valve to shut off the coolant venting via the PORV, but around 32,000 gallons (120 m³) of coolant had already leaked from the primary loop.[18] It was not until 165 minutes after the start of the problem that radiation alarms activated as contaminated water reached detectors — by that time, the radiation levels in the primary coolant water were around 300 times expected levels, and the plant was seriously contaminated.

[edit] Emergency declared

At 6:56 a.m. a plant supervisor declared a site emergency, and less than half an hour later station manager Gary Miller announced a general emergency, defined as having the "potential for serious radiological consequences" to the general public.[19] Met Ed notified the Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency (PEMA), which in turn contacted state and local agencies, governor Richard L. Thornburgh and lieutenant governor William W. Scranton, to whom Thornburgh assigned responsibility for collecting and reporting on information about the accident.[20] The uncertainty of operators at the plant was reflected in fragmentary, ambiguous, or contradictory statements made by Met Ed to government agencies and to the press, particularly about the possibility and severity of off-site radiation releases. Scranton held a press conference in which he was reassuring, yet confusing, about this possibility, and his statements that though there had been a "small release of radiation,...[and] no increase in normal radiation levels" had been detected; was contradicted by another official and by statements from Met Ed claiming no radiation had been released.[21] In fact, readings from instruments at the plant and off-site detectors had detected radiation releases, albeit at levels that were unlikely to threaten public health as long as they were temporary, and providing that containment of the then highly contaminated reactor was maintained.[22]

Angry that Met Ed had not informed them before conducting a steam venting from the plant and convinced that the company was downplaying the severity of the accident, state officials turned to the NRC.[23] After receiving word of the accident from Met Ed, the NRC had activated its emergency response headquarters in Bethesda, Maryland and sent staff members to Three Mile Island. NRC chairman Joseph Hendrie and commissioner Victor Gilinsky[24] initially viewed the accident as a "cause for concern but not alarm".[25] Gilinsky briefed reporters and members of Congress on the situation and informed White House staff, and at 10:00 A.M. met with two other commissioners. However, the NRC faced the same problems in obtaining accurate information as the state, and was further hampered by being organizationally ill-prepared to deal with emergencies, as it lacked a clear command structure and the authority to tell the utility what to do, or to order an evacuation of the local area.[26]

Gilinsky wrote in a recent article that it took five weeks it to learn that "the reactor operators had measured fuel temperatures near the melting point."[27] He further wrote: "We didn't learn for years--until the reactor vessel was physically opened--that by the time the plant operator called the NRC at about 8 a.m., roughly one-half of the uranium fuel had already melted."[27]

It was still not clear to the control room staff that the primary loop water levels were low and that over half the core was exposed. A group of workers took manual readings from the thermocouples and obtained a sample of primary loop water. Seven hours into the emergency, new water was pumped into the primary loop and the backup relief valve was opened to reduce pressure so that the loop could be filled with water. After 16 hours, the primary loop pumps were turned on once again, and the core temperature began to fall. A large part of the core had melted, and the system was still dangerously radioactive. Over the next week, steam and hydrogen were removed from the reactor using a plasma recombiner and, more controversially, by venting straight to the atmosphere.

[edit] Radiation release

According to the official figures, as compiled by the 1979 Kemeny Commission from Metropolitan Edison and NRC data, a maximum of 13 million curies (480 petabecquerels) of radioactive noble gases (primarily xenon) were released by the event.[1] However these noble gases were considered relatively harmless,[28] and only 13 to 17 curies of thyroid cancer-causing iodine-131 were released.[1] Total releases according to these figures were a relatively small proportion of the estimated 10 billion curies in the reactor.[28] It was later found that about half the core had melted, and the cladding around 90% of the fuel rods had failed,[6][29] with five feet of the core gone, and around 20 tons of uranium flowing to the bottom head of the pressure vessel.[30] However, the reactor vessel maintained integrity and contained the damaged fuel.[31]

However, the official figures are not uncontested. Independent measurements provided evidence of radiation levels up to five times higher than normal in locations hundreds of miles downwind from TMI.[32] [33] According to Randall Thompson, the lead health physicist at TMI after the accident (a veteran of the US Navy nuclear submarine program and a self-confessed "nuclear geek"), radiation releases were hundreds if not thousands of times higher.[28] [34] Some other insiders, including Arnie Gundersen, a former nuclear industry executive turned whistle-blower,[35] concur; Gundersen offers evidence, based on pressure monitoring data, for a hydrogen explosion shortly before 2 p.m. on on 28 March 1979, which would have provided the means for a high dose of radiation to occur.[28] Gundersen cites affidavits from four reactor operators according to which the plant manager was aware of a dramatic pressure spike, after which the internal pressure dropped to outside pressure. Gundersen also notes that the control room shook and doors were blown off hinges. However official NRC reports refer merely to a "hydrogen burn." [28] The Kemeny Commission referred to "a burn or an explosion that caused pressure to increase by 28 pounds per square inch in the containment building".[36] The Washington Post reported that "At about 2 p.m., with pressure almost down to the point where the huge cooling pumps could be brought into play, a small hydrogen explosion jolted the reactor."[37]

A later scientific study noted that the official emission figures were consistent with available dosimeter data,[38] though others have noted the incompleteness of this data, particularly for releases early on.[39]

[edit] Aftermath

[edit] Investigations

Several state and federal government agencies mounted investigations into the crisis, the most prominent of which was the President's Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island, created by Jimmy Carter in April 1979.[40] The commission consisted of a panel of twelve people, specifically chosen for their lack of strong pro- or antinuclear views, and headed by chairman John G. Kemeny, president of Dartmouth College. It was instructed to produce a final report within six months, and after public hearings, depositions, and document collection, released a completed study on October 31, 1979.[41] Though the study avoided drawing conclusions about the future of the nuclear industry, it strongly criticized Babcock and Wilcox, Met Ed, GPU, and the NRC for lapses in quality assurance and maintenance, inadequate operator training, lack of communication of important safety information, poor management, and complacency.[42]

The Kemeny Commission noted that Babcock and Wilcox's PORV valve had previously failed on 11 occasions, 9 of them in the open position, allowing coolant to escape. More disturbing, however, was the fact that virtually the entire sequence of events at TMI had been duplicated 18 months earlier at another Babcock and Wilcox reactor, owned by Davis-Besse. The only difference was that the operators at Davis-Besse identified the valve failure after 20 minutes, where at TMI it took 2 hours and 20 minutes; and the Davis-Besse facility was operating at 9% power, against TMI's 97%. Although Babcock engineers recognised the problem, the company failed to clearly notify its customers of the valve issue.[43]

The Pennsylvania House of Representatives conducted its own investigation, which focused on the need to improve evacuation procedures.

[edit] Effect on nuclear power industry

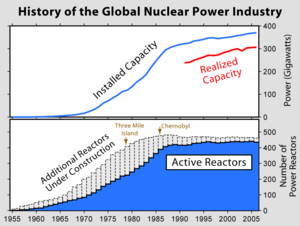

According to the IAEA, the Three Mile Island accident was a significant turning point in the global development of nuclear power [44]. From 1963 to 1979, the number of reactors under construction globally increased every year except 1971 and 1978. However, following the event, the number of reactors under construction declined every year from 1980 to 1998. Many similar Babcock and Wilcox reactors on order were canceled — in total, 51 American nuclear reactors were canceled from 1980 to 1984.[citation needed]

The 1979 TMI accident did not, however, initiate the demise of the U.S. nuclear power industry. As a result of post-oil-shock analysis and conclusions of overcapacity, 40 planned nuclear power plants had already been canceled between 1973 and 1979. No U.S. nuclear power plant had been authorized to begin construction since the year before TMI. Nonetheless, at the time of the TMI incident, 129 nuclear power plants had been approved; of those, only 53 (which were not already operating) were completed. Federal requirements became more stringent, local opposition became more strident, and construction times were significantly lengthened.

[edit] Cleanup

The TMI cleanup started in August 1979 and officially ended in December 1993, having cost around US$975 million. From 1985 to 1990 almost 100 tons of radioactive fuel were removed from the site. However, the contaminated cooling water that leaked into the containment building had seeped into the building's concrete, leaving the radioactive residue impossible to remove.[citation needed] TMI-2 had been online only three months but now had a ruined reactor vessel and a containment building that was unsafe to walk in — it has since been permanently closed.

Three Mile Island Unit 2 was too badly damaged and contaminated to resume operations. The reactor was gradually deactivated and mothballed in a lengthy process completed in 1993.[citation needed] Initially, efforts focused on the cleanup and decontamination of the site, especially the defueling of the damaged reactor. In 1988, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced that, although it was possible to further decontaminate the Unit 2 site, the remaining radioactivity had been sufficiently contained as to pose no threat to public health and safety. Accordingly, further cleanup efforts were deferred to allow for decay of the radiation levels and to take advantage of the potential economic benefits of retiring both Unit 1 and Unit 2 together. The defueling process was completed in 1990, and the damaged fuel was removed and disposed of in 1993.[citation needed]

[edit] Health effects and epidemiology

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Please see the relevant discussion on the talk page. (April 2009) |

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (April 2009) |

In the aftermath of the accident, investigations focussed on the amount of radiation released by the accident. According to the American Nuclear Society, using the relatively low official radiation emission figures, "The average radiation dose to people living within ten miles of the plant was eight millirem, and no more than 100 millirem to any single individual. Eight millirem is about equal to a chest X-ray, and 100 millirem is about a third of the average background level of radiation received by US residents in a year."[31][45] To put this dose into context, while the average background radiation in the US is about 360 millirem per year, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission regulates all workers' of any US nuclear power plant exposure to radiation to a total of 5000 millirem per year.[46] Based on these low emission figures, early scientific publications on the health effects of the fallout estimated one or two additional cancer deaths in the 10-mile area around TMI.[32] Disease rates in areas further than 10 miles from the plant were never examined.[32]

The official figures are too low to account for the acute health effects reported by some local residents and documented in two books;[47] [48] such health effects require exposure to at least 100,000 millirems (100 rems) to the whole body - 1000 times less than the official estimates.[49] The reported health effects are consistent with high doses of radiation, and comparable to the experiences of cancer patients undergoing radio-therapy;[28] but have many other potential causes.[49] The effects included "metallic taste, erythema, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, deaths of pets and farm and wild animals, and damage to plants."[50] Some local statistics showed dramatic one-year changes amongst the most vulnerable: "In Dauphin County, where the Three Mile Island plant is located, the 1979 death rate among infants under one year represented a 28 percent increase over that of 1978; and among infants under one month, the death rate increased by 54 percent."[32] Physicist Ernest Sternglass, a specialist in low-level radiation, noted these statistics in the 1981 edition of his book Secret Fallout: low-level radiation from Hiroshima to Three-Mile Island. In their final 1981 report, however, the Pennsylvania Department of Health, examining death rates within the 10-mile area around TMI for the 6 months after the accident, said that the TMI-2 accident did not cause local deaths of infants or fetuses.[51] [52]

Scientific work continued in the 1980s, but focussed heavily on the mental health effects due to stress,[32] as the Kemeny Commission had concluded that this was the sole public health effect.[53] A 1984 survey by a local psychologist of 450 local residents, documenting acute radiation health effects (as well as 19 cancers 1980-84 amongst the residents against an expected 2.6[50]), ultimately led the TMI Public Health Fund reviewing the data[54] and supporting a comprehensive epidemiological study by a team at Columbia University.[28] In 1990-1 this team, led by Maureen Hatch, carried out the first epidemiological study on local death rates before and after the accident, for the period 1975-1985, for the 10-mile area around TMI.[53][55] Assigning fallout impact based on winds on the morning of March 28, 1979,[55] the study found no link between fallout and cancer risk.[32] The study found that cancer rates near the Three Mile Island plant peaked in 1982-3, but their mathematical model did not account for the observed increase in cancer rates, since they argued that latency periods for cancer are much longer than three years. The study concludes that stress may have been a factor (though no specific biological mechanism was identified), and speculated that changes in cancer screening were more important.[53] Subsequently lawyers for 2000 residents asked epidemiologist Stephen Wing of the University of North Carolina, a specialist in nuclear radiation exposure, to re-examine the Columbia study. Wing was reluctant to get involved, later writiing that "allegations of high radiation doses at TMI were considered by mainstream radiation scientists to be a product of radiation phobia or efforts to extort money from a blameless industry."[50] Wing later noted that in order to obtain the relevant data, the Columbia study had to submit to what Wing called "a manipulation of research" in the form of a court order which prohibited "upper limit or worst case estimates of releases of radioactivity or population doses... [unless] such estimates would lead to a mathematical projection of less than 0.01 health effects."[50] Wing found cancer rates raised within a 10-mile radius two years after the accident by 0.034% +/- 0.013%, 0.103% +/- 0.035%, and 0.139% +/- 0.073% for all cancer, lung cancer, and leukemia, respectively.[56] An exchange of published responses between Wing and the Columbia team followed.[32] Wing later noted a range of studies showing latency periods for cancer from radiation exposure between 1 and 5 years due to immune system suppression.[50] Latencies between 1 and 9 years have been studied in a variety of contexts ranging from the Hiroshima survivors and the fallout from Chernobyl to therapeutic radiation; a 5-10 year latency is most common.[57]

On the recommendation of the Columbia team, the TMI Public Health Fund followed up its work with a longitudinal study.[38] The 2000-3 University of Pittsburgh study[58] compared post-TMI death rates in different parts of the local area, again using the wind direction on the morning of 28 March to assign fallout impact, even though, according to Joseph Mangano in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the areas of lowest fallout by this criterion had the highest mortality rates.[32] In contrast to the Columbia study, which estimated exposure in 69 areas, the Pittsburgh study drew on the TMI Population Registry, compiled by the Pennsylvania Department of Health. This was based on radiation exposure information on 93% of the population living within five miles of the nuclear plant - nearly 36,000 people, gathered in door-to-door surveys shortly after the accident.[59] The study found slight increases in cancer and mortality rates but "no consistent evidence" of causation by TMI.[58] Wing et al criticised the Pittsburgh study for making the same assumption as Columbia: that the official statistics on low doses of radiation were correct - leading to a study "in which the null hypothesis cannot be rejected due to a priori assumptions."[60] Hatch et al noted that their assumption had been backed up by dosimeter data,[38] though Wing et al noted the incompleteness of this data, particularly for releases early on.[61]

In 2005 R. William Field, an epidemiologist at the University of Iowa, who first described radioactive contamination of the wild food chain from the accident[citation needed] suggested that some of the increased cancer rates noted around TMI were related to the area's very high levels of natural radon, noting that according to a 1994 EPA study, the Pennsylvania counties around TMI have the highest regional screening radon concentrations in the 38 states surveyed.[62] The factor had also been considered by the Pittsburgh study[58] and by the Columbia team, which had noted that "rates of childhood leukemia in the Three Mile Island area are low compared with national and regional rates."[55] A 2006 study on the standard mortality rate in children in 34 counties downwind of TMI found an increase in the rate (for cancers other than leukaemia) from 0.83 (1979-83) to 1.17 (1984-88), meaning a rise from below the national average to above it.[57]

A 2008 study on thyroid cancer in the region found rates as expected in the county in which the reactor is located, and significantly higher than expected rates in two neighbouring counties beginning in 1990 and 1995 respectively. The research notes that "These findings, however, do not provide a causal link to the TMI accident."[63] Mangano (2004) notes three large gaps in the literature: no study has focussed on infant mortality data, or on data from outside the 10-mile zone, or on radioisotopes other than iodine, krypton, and xenon.[32]

[edit] Activism and legal action

| This section's factual accuracy is disputed. Please see the relevant discussion on the talk page. (April 2009) |

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Please see the discussion on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until the dispute is resolved. (April 2009) |

| Please help improve this article or section by expanding it. Further information might be found on the talk page. (April 2009) |

In 1981 citizens' groups succeeded in a class action suit against TMI, winning $25m in an out-of-court settlement. Part of this money was used to found the TMI Public Health Fund.[64]

Radiation and Public Health Project, an anti-nuclear group, cited calculations by Joseph Mangano, a long-time crusader against nuclear energy who has authored 19 medical journal articles and a book on Low Level Radiation and Immune Disease, that reported a spike in infant mortality in the downwind communities two years after the accident.[65][66] Anecdotal evidence also records effects on the region's wildlife.[32] For example, according to one journalist and anti-nuclear activist, Harvey Wasserman, the fallout caused "a plague of death and disease among the area's wild animals and farm livestock," including a sharp fall in the reproductive rate of the region's horses and cows, reflected in statistics from Pennsylvania's Department of Agriculture, though the Dept denies a link with TMI.[67]

Hundreds of out-of-court settlements have been reached with alleged victims of the fallout, with a total of $15m paid out to parents of children born with birth defects.[68] However, a class action lawsuit alleging that the accident caused detrimental health effects was rejected by Harrisburg U.S. District Court Judge Sylvia Rambo. The appeal of the decision in front of U.S. Third Circuit Court of Appeals also failed.[69]

[edit] Lessons learned

| This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2008) |

Three Mile Island has been of interest to human factors engineers as an example of how groups of people react to and make decisions under stress. There is now a general consensus that the accident was exacerbated by wrong decisions made because the operators were overwhelmed with information, much of it irrelevant, misleading or incorrect. As a result of the TMI-2 incident, nuclear reactor operator training has been improved. Before the incident it focused on diagnosing the underlying problem; afterward, it focused on reacting to the emergency by going through a standardized checklist to ensure that the core is receiving enough coolant under sufficient pressure.

In addition to the improved operating training, improvements in quality assurance, engineering, operational surveillance and emergency planning have been instituted. Improvements in control room habitability, "sight lines" to instruments, ambiguous indications and even the placement of "trouble" tags were made; some trouble tags were covering important instrument indications during the accident. Improved surveillance of critical systems, structures and components required for cooling the plant and mitigating the escape of radionuclides during an emergency were also implemented. In addition, each nuclear site needed to have an approved emergency plan to direct the evacuation of the public within a ten mile Emergency Planning Zone (EPZ); and to facilitate rapid notification and evacuation. This plan is periodically rehearsed with federal and local authorities to ensure that all groups work together quickly and efficiently.

In the end, a few simple water level gauges on the reactor vessel might have prevented the accident. The operators' focus on a single misleading indication, the level in the pressurizer, was a significant contributing factor to the partial meltdown.

In 1979, as Pennsylvania state secretary of health in the Thornburg administration, Gordon K MacLeod, MD, managed the health effects of the Three Mile Island nuclear accident. He criticized Pennsylvania's preparedness, in the event of a nuclear accident, at the time for not having potassium iodide in stock, which protects the thyroid gland in the event of exposure to radioactive iodine, as well as for not having any physicians on Pennsylvania's equivalent to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The Three Mile Island accident inspired Charles Perrow's 1982 exposition of Normal Accident Theory, which became widely known through his 1984 book. TMI was an example of this type of accident because it was "unexpected, incomprehensible, uncontrollable and unavoidable".[70]

[edit] The China Syndrome

The accident at the plant occurred 12 days after the release of the movie The China Syndrome, which featured Jane Fonda as a news anchor at a California TV station. In the film, a major nuclear plant failure almost happens while Fonda's character and her cameraman Michael Douglas are at a plant doing a series on nuclear power. She proceeds to raise awareness of how unsafe the plant was. Coincidentally, there is a scene in which Fonda's character speaks with a nuclear safety expert who says that a meltdown could render an area "the size of Pennsylvania permanently uninhabitable." Also, the fictional near-accident in the movie stems from plant operators overestimating the amount of water within the core.

After the release of the film, Fonda began lobbying against nuclear power — the only actor in the film to do so. In an attempt to counter her efforts, the nuclear physicist Edward Teller, "father of the hydrogen bomb" and long-time government science advisor, himself lobbied in favor of nuclear power, and the 71-year-old scientist eventually suffered a heart attack on May 8, 1979, which he later blamed on Fonda: "You might say that I was the only one whose health was affected by that reactor near Harrisburg. No, that would be wrong. It was not the reactor. It was Jane Fonda. Reactors are not dangerous."[71]

[edit] Current status

Unit 1 had its license temporarily suspended following the incident at Unit 2. Although the citizens of the three counties surrounding the site voted by a margin of 3:1 to permanently retire Unit 1, it was permitted to resume operations in 1985.[citation needed] General Public Utilities Corporation, the plant's owner, formed General Public Utilities Nuclear Corporation (GPUN) as a new subsidiary to own and operate the company's fleet of nuclear facilities, including Three Mile Island. The plant had previously been operated by Metropolitan Edison Company (Met-Ed), one of GPU's regional utility operating companies. In 1996, General Public Utilities shortened its name to GPU Inc. Three Mile Island Unit 1 was sold to AmerGen Energy Corporation, a joint venture between Philadelphia Electric Company (PECO), and British Energy, in 1998.[citation needed] In 2000, PECO merged with Unicom Corporation to form Exelon Corporation, which acquired British Energy's share of AmerGen in 2003.[citation needed] Today, AmerGen LLC is a fully owned subsidiary of Exelon Generation and owns TMI Unit 1, Oyster Creek Nuclear Generating Station, and Clinton Power Station. These three units, in addition to Exelon's other nuclear units, are operated by Exelon Nuclear Inc., an Exelon subsidiary.

General Public Utilities was legally obliged to continue to maintain and monitor the site, and therefore retained ownership of Unit 2 when Unit 1 was sold to AmerGen in 1998. GPU Inc. was acquired by First Energy Corporation in 2001, and subsequently dissolved. First Energy then contracted out the maintenance and administration of Unit 2 to AmerGen. Unit 2 has been administered by Exelon Nuclear since 2003, when Exelon Nuclear's parent company, Exelon, bought out the remaining shares of AmerGen, inheriting First Energy's maintenance contract. Unit 2 continues to be licensed and regulated by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in a condition known as Post Defueling Monitored Storage (PDMS).[72]

Today, the TMI-2 reactor is permanently shut down and defueled, with the reactor coolant system drained, the radioactive water decontaminated and evaporated, radioactive waste shipped off-site to a disposal site, reactor fuel and core debris shipped off-site to a Department of Energy facility, and the remainder of the site being monitored. The owner says it will keep the facility in long-term, monitored storage until the operating license for the TMI-1 plant expires at which time both plants will be decommissioned.[6] TMI-1's current license expires in 2014. On January 8, 2008, AmerGen Energy Corporation, the operator of TMI-1, submitted a license renewal application to the NRC. If the license is renewed, TMI-1's license will be extended to 2034.[73]

[edit] Timeline

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| July 1980 | Approximately 43,000 curies of krypton were vented from the reactor building. |

| July 1980 | The first manned entry into the reactor building took place. |

| Nov. 1980 | An Advisory Panel for the Decontamination of TMI-2, composed of citizens, scientists, and State and local officials, held its first meeting in Harrisburg, PA. |

| July 1984 | The reactor vessel head (top) was removed. |

| Oct. 1985 | Defueling began. |

| July 1986 | The off-site shipment of reactor core debris began. |

| Aug. 1988 | GPU submitted a request for a proposal to amend the TMI-2 license to a "possession-only" license and to allow the facility to enter long-term monitoring storage. |

| Jan. 1990 | Defueling was completed. |

| July 1990 | GPU submitted its funding plan for placing $229 million in escrow for radiological decommissioning of the plant. |

| Jan. 1991 | The evaporation of accident-generated water began. |

| April 1991 | NRC published a notice of opportunity for a hearing on GPU's request for a license amendment. |

| Feb. 1992 | NRC issued a safety evaluation report and granted the license amendment. |

| Aug. 1993 | The processing of accident-generated water was completed involving 2.23 million gallons. |

| Sept. 1993 | NRC issued a possession-only license. |

| Sept. 1993 | The Advisory Panel for Decontamination of TMI-2 held its last meeting. |

| Dec. 1993 | Post-Defueling Monitoring Storage began. |

[edit] See also

- International Nuclear Events Scale

- Nuclear and radiation accidents | List of civilian nuclear accidents

- Nuclear meltdown | Loss of coolant accident

- Nuclear safety | Nuclear power | Radiation

- Radioactive contamination

- Anti-nuclear

[edit] References

- ^ a b c Walker, p. 231

- ^ Kemeny, p. 12

- ^ Walker, pp. 234-237

- ^ Stephen J. Dubner and Steven D. Levitt (2007-09-16). "The Jane Fonda Effect". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/16/magazine/16wwln-freakonomics-t.html?_r=1. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ Tom McKenna (2004-08-10). "Lessons from Three Mile Island". Physics World. http://physicsworld.com/cws/article/print/19964.

- ^ a b c "Fact Sheet on the Three Mile Island Accident". U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/3mile-isle.html. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ^ Walker, p. 71

- ^ Walker, pp. 72-73

- ^ a b The Washington Post, A Pump Failure and Claxon Alert

- ^ Le Bot, Pierre (2004), "Human reliability data, human error and accident models—illustration through the Three Mile Island accident analysis", Reliability Engineering & System Safety, Volume 83, Issue 2, February 2004, Pages 153-167

- ^ Walker, pp. 73-74

- ^ Rogovin, pp. 14-15

- ^ Kemeny, p. 94

- ^ Rogovin, p. 16

- ^ Kemeny, p. 96; Rogovin, pp. 17-18

- ^ Kemeny, p. 96

- ^ Kemeny, p. 99

- ^ Rogovin, p. 19; Walker, p. 78

- ^ Walker, p. 79

- ^ Walker, pp. 80-81

- ^ Walker, pp. 80-84

- ^ Walker, pp. 84-86

- ^ Walker, p. 87

- ^ [NRC: Victor Gilinsky, http://www.nrc.gov/about-nrc/organization/commission/former-commissioners/gilinsky.html]

- ^ Walker p. 89

- ^ Walker, pp. 90-91

- ^ a b Gilinsky, Victor (23 March 2009). "Behind the scenes of Three Mile Island". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. http://thebulletin.org/web-edition/features/behind-the-scenes-of-three-mile-island. Retrieved on 2009-03-31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sue Sturgis (2009) "FOOLING WITH DISASTER? Startling revelations about Three Mile Island disaster raise doubts over nuclear plant safety", Facing South: Online Magazine of the Institute for Southern Studies, April 2009

- ^ Kemeny, p. 30

- ^ McEvily Jr., AJ and Le May, I. (2002), "The accident at Three Mile Island", Materials science research international, vol:8 iss:1 pg:1 -8

- ^ a b "What Happened and What Didn't in the TMI-2 Accident". American Nuclear Society. http://www.ans.org/pi/resources/sptopics/tmi/whathappened.html. Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mangano, Joseph (2004), "Three Mile Island: Health study meltdown", Bulletin of the atomic scientists, 60(5), pp31 -35

- ^ "In 1980, Science magazine published an article by New York state health officials who had measured levels of airborne xenon 133 in Albany that were three times above normal for five days after the meltdown (xenon 133 has a half-life of 5.3 days). A University of Southern Maine professor, Charles Armentrout, also documented elevated airborne beta radioactivity in Portland for several days following the accident. Both Albany and Portland lie north/northeast of the plant, about 230 and 430 miles distant." (Mangano 2004)

- ^ Thompson and Bear (1995), TMI Assessment (Part 2)

- ^ http://www.tmia.com/march26 Video: TMI and Community Health] - Gundersen 30th anniversary testimony for the Pennsylvania Legislature

- ^ Kemeny, John G., (Chairman, 1979), President's Commission: The Need For Change: The Legacy Of TMI

- ^ The Washington Post The Tough Fight to Confine the Damage

- ^ a b c Hatch et al (1997), Comments on "A Re-Evaluation of Cancer Incidence Near the Three Mile Island Nuclear Plant", Environmental Health Perspectives, 105(1)

- ^ [1]

- ^ Walker, pp. 209-210

- ^ Walker, p. 210

- ^ Walker, pp. 211-212

- ^ Hopkins, A. (2001), "Was Three Mile Island a 'normal accident'?", Journal of contingencies and crisis management, vol:9 iss:2 pg:65 -72

- ^ "50 Years of Nuclear Energy". IAEA. http://www.iaea.org/About/Policy/GC/GC48/Documents/gc48inf-4_ftn3.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ "Three-Mile Island cancer rates probed". BBC News. 2002-11-01. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/2385551.stm. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ^ "NRC: Fact Sheet on Biological Effects of Radiation". http://www.nrc.gov/reading-rm/doc-collections/fact-sheets/bio-effects-radiation.html. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ Katagiri Mitsuru and Aileen M. Smith (1989), Three Mile Island: The People's Testament - based on interviews with 250 residents between 1979 and 1988.

- ^ Robert Del Tredici (1982) The People of Three Mile Island, Random House, Inc.

- ^ a b GPU Utilities 91986), "Radiation And Health Effects: A Report on the TMI-2 Accident and Related Health Studies"

- ^ a b c d e Wing, Steven (2003) "Objectivity and Ethics in Environmental Health Science", Environmental Health Perspectives Volume 111, Number 14, November 2003

- ^ "Report doubts infant death rise from three mile island mishap". The New York Times. 1981-03-21. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?sec=health&res=9D06E3D61239F932A15750C0A967948260. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ Walker, p234

- ^ a b c Hatch MC, Wallenstein S, Beyea J, Nieves JW, Susser M (June 1991). "Cancer rates after the Three Mile Island nuclear accident and proximity of residence to the plant". American Journal of Public Health 81 (6): 719–724. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1405170. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ Moholdt B. Summary of acute symptoms by TMI area residents during accident. In:Proceedings of the workshop on Three Mile Island dosimetry. Philadelphia:Academy of Natural Sciences, 1985.

- ^ a b c Maureen C. Hatch et al (1990). "Cancer near the Three Mile Island Nuclear Plant: Radiation Emissions". American Journal of Epidemiology (Oxford Journals) 132 (3): 397-412. http://aje.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/132/3/397.

- ^ Stephen Wing et al. (1997). "A Re-Evaluation of Cancer Incidence Near the Three Mile Island Nuclear Plant". 52-57. http://www.ehponline.org/docs/1997/105-1/wingabs.html.

- ^ a b Mangano, Joseph (2006), "A short latency between radiation exposure from nuclear plants and cancer in young children", International journal of health services, vol:36 iss:1 pg:113-135

- ^ a b c Evelyn O. Talbott et al., “Mortality Among the Residents of the Three Mile Accident Area: 1979–1992,” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 108, no. 6, pp. 545–52 (2000); Evelyn O. Talbott et al., “Long-Term Follow-up of the Residents of the Three Mile Island Accident,” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 111, no. 3, pp.341–48 (2003)

- ^ Holzman (2003), "Cancer and three mile island", Environmental health perspectives, vol:111 iss:3 pg:A166 -A167

- ^ Wing, S. and Richardson, D. (2000), "Collision of Evidence and Assumptions: TMI Déjà View", Environmental Health Perspectives, 108(12), December 2000

- ^ [2]

- ^ R. W. Field (2005), "Three Mile Island epidemiologic radiation dose assessment revisited: 25 years after the accident", Radiation Protection Dosimetry 113 (2), pp. 214-217

- ^ RJ Levin (2008), "Incidence of thyroid cancer in residents surrounding the three mile island nuclear facility", Laryngoscope 118 (4), pp. 618-628

- ^ Gayle Greene The Woman Who Knew Too Much: Alice Stewart

- ^ Mangano, Joseph (September/October 2004). "Three Mile Island: Health Study Meltdown". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (Metapress) 60 (5): pp. 30-35. doi:. ISSN 0096-3402. http://thebulletin.metapress.com/content/t0778475220w1365/?p=8a680f7b0d2b41c886fd55813b30268b&pi=0. Retrieved on 2009-03-31.

- ^ "US nuclear industry powers back into life". The Guardian. 2004-04-13. http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2004/apr/13/nuclearindustry.usnews. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

- ^ Harvey Wasserman, CounterPunch, 24 March 2009, People Died at Three Mile Island

- ^ Harvey Wasserman, 1 April 2009, CounterPunch, Cracking the Media Silence on Three Mile Island

- ^ "Three Mile Island: 1979". World Nuclear Association. http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/inf36.htm. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.

- ^ Perrow, C. (1982), ‘The President’s Commission and the Normal Accident’, in Sils, D., Wolf, C. and Shelanski, V. (Eds), Accident at Three Mile Island: The Human Dimensions, Westview, Boulder, pp.173–184.

- ^ Melvin A Benarde (2007). Our Precarious Habitat-- It's in Your Hands. Wiley InterScience. p. 256. ISBN 0471740659. http://books.google.com/books?id=9O82L8QEZXcC&pg=PA256.

- ^ "NRC: Three Mile Island - Unit 2". http://www.nrc.gov/info-finder/decommissioning/power-reactor/three-mile-island-unit-2.html. Retrieved on 2009-01-29.

- ^ Exelon Corporation (2008-01-08). AmerGen Submits TMI License Renewal Application to NRC. Press release. http://www.threemileislandinfo.com/news/detail.aspx?id=7. Retrieved on 2008-12-29.

[edit] Bibliography

- Kemeny, John G. (October 1979). Report of The President's Commission on the Accident at Three Mile Island: The Need for Change: The Legacy of TMI. Washington, D.C.: The Commission. ISBN 0935758003. http://www.threemileisland.org/downloads/188.pdf.

- Rogovin, Mitchell (1980). Three Mile Island: A report to the Commissioners and to the Public, Volume I. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Special Inquiry Group. http://www.threemileisland.org/downloads/354.pdf.

- Walker, J. Samuel (2004). Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23940-7. (Google Books)

[edit] External links

- TMI web page from the US Department of Energy's Energy Information Administration

- "Three Mile Island 1979 Emergency" - website about the accident, with many reports and other documents relating to the accident, created by nearby Dickinson College

- Step-By-Step account of the accident with illustrations from pbs.org

- Three Mile Island Alert, the watchdog group that warned the public for nearly two years that reactor #2 was dangerously faulty.[citation needed] What's wrong with the "fact sheet" purports to correct errors in the NRC report.

- EFMR citizens radiation monitoring group for the Three Mile Island and Peach Bottom nuclear plants

- Annotated bibliography for Three Mile Island from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Video and audio relating to the Three Mile Island accident, from the Dick Thornburgh Papers at University of Pittsburgh.

- Killing Our Own a review of subsequent casualties by Harvey Wasserman and Norman Solomon with Robert Alveraez and Eleanore Walters

- Three Mile Island -- Failure Of Science Or Spin?, Science Daily

- 1979 - Three Mile Island A report from Steve Holt of WCBS Newsradio 880 (WCBS-AM New York) Part of WCBS 880's celebration of 40 years of newsradio.

- Crisis at Three Mile Island by The Washington Post

- People Died at Three Mile Island by Harvey Wasserman