Dopamine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Dopamine | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| IUPAC name |

|

| Other names | 2-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl)ethylamine; 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine; 3-hydroxytyramine; DA; Intropin; Revivan; Oxytyramine |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 51-61-6, 62-31-7 (hydrochloride) |

| PubChem | |

| SMILES |

|

| ChemSpider ID | |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C8H11NO2 |

| Molar mass | 153.178 |

| Melting point |

128 °C, 401 K, 262 °F |

| Solubility in water | 60.0 g/100 ml |

| Hazards | |

| R-phrases | R36/37/38 |

| S-phrases | S26 S36 |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter occurring in a wide variety of animals, including both vertebrates and invertebrates. In the brain, this phenethylamine functions as a neurotransmitter, activating the five types of dopamine receptors — D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5, and their variants. Dopamine is produced in several areas of the brain, including the substantia nigra and the ventral tegmental area.[1] Dopamine is also a neurohormone released by the hypothalamus. Its main function as a hormone is to inhibit the release of prolactin from the anterior lobe of the pituitary.

Dopamine can be supplied as a medication that acts on the sympathetic nervous system, producing effects such as increased heart rate and blood pressure. However, because dopamine cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, dopamine given as a drug does not directly affect the central nervous system. To increase the amount of dopamine in the brains of patients with diseases such as Parkinson's disease and dopa-responsive dystonia, L-DOPA (levodopa), which is the precursor of dopamine, can be given because it can cross the blood-brain barrier.

[edit] History

Dopamine was discovered in 1958 by Arvid Carlsson and Nils-Åke Hillarp at the Laboratory for Chemical Pharmacology of the National Heart Institute of Sweden. It was named dopamine because it was a monoamine, and its synthetic precursor was 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA).[2] Arvid Carlsson was awarded the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for showing that dopamine is not just a precursor of norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and epinephrine (adrenaline) but a neurotransmitter, as well.

Dopamine was first synthesized in 1910 by George Barger and James Ewens at Wellcome Laboratories in London, England.[3]

[edit] Biochemistry

[edit] Name and family

Dopamine has the chemical formula C6H3(OH)2-CH2-CH2-NH2. Its chemical name is "4-(2-aminoethyl)benzene-1,2-diol" and its abbreviation is "DA."

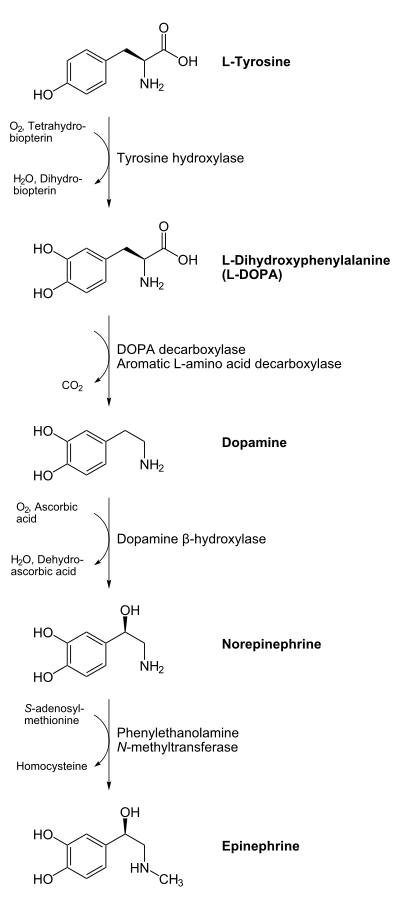

As a member of the catecholamine family, dopamine is a precursor to norepinephrine (noradrenaline) and then epinephrine (adrenaline) in the biosynthetic pathways for these neurotransmitters.

[edit] Biosynthesis

Dopamine is biosynthesized in the body (mainly by nervous tissue and the medulla of the adrenal glands) first by the hydroxylation of the amino acid L-tyrosine to L-DOPA via the enzyme tyrosine 3-monooxygenase, also known as tyrosine hydroxylase, and then by the decarboxylation of L-DOPA by aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (which is often referred to as dopa decarboxylase). In some neurons, dopamine is further processed into norepinephrine by dopamine beta-hydroxylase.

In neurons, dopamine is packaged after synthesis into vesicles, which are then released into the synapse in response to a presynaptic action potential.

[edit] Inactivation and degradation

Dopamine is inactivated by reuptake via the dopamine transporter, then enzymatic breakdown by catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) and monoamine oxidase (MAO). Dopamine that is not broken down by enzymes is repackaged into vesicles for reuse.

Dopamine may also simply diffuse away from the synapse, and help to regulate blood pressure.

[edit] Functions in the brain

Dopamine has many functions in the brain, including important roles in behavior and cognition, motor activity, motivation and reward, inhibition of prolactin production (involved in lactation), sleep, mood, attention, and learning. Dopaminergic neurons (i.e., neurons whose primary neurotransmitter is dopamine) are present chiefly in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) of the midbrain, substantia nigra pars compacta, and arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus.

A common hypothesis, though not uncontroversial[4], is that dopamine has a function of transmitting reward prediction error. According to this hypothesis, the phasic responses of dopamine neurons are observed when an unexpected reward is presented. These responses transfer to the onset of a conditioned stimulus after repeated pairings with the reward. Further, dopamine neurons are depressed when the expected reward is omitted. Thus, dopamine neurons seem to encode the prediction error of rewarding outcomes. In nature, we learn to repeat behaviors that lead to maximize rewards. Dopamine is therefore believed to provide a teaching signal to parts of the brain responsible for acquiring new behavior. Temporal difference learning provides a computational model describing how the prediction error of dopamine neurons is used as a teaching signal.

In insects, a similar reward system exists, using octopamine, a chemical relative of dopamine.[5]

[edit] Anatomy

Dopaminergic neurons form a neurotransmitter system which originates in substantia nigra pars compacta, ventral tegmental area (VTA), and hypothalamus. These project axons to large areas of the brain through four major pathways:

This innervation explains many of the effects of activating this dopamine system. For instance, the mesolimbic pathway connects the VTA and nucleus accumbens; both are central to the brain reward system.[6]

[edit] Movement

Via the dopamine receptors, D1-5, dopamine reduces the influence of the indirect pathway, and increases the actions of the direct pathway within the basal ganglia. Insufficient dopamine biosynthesis in the dopaminergic neurons can cause Parkinson's disease, in which a person loses the ability to execute smooth, controlled movements.

[edit] Cognition and frontal cortex

In the frontal lobes, dopamine controls the flow of information from other areas of the brain. Dopamine disorders in this region of the brain can cause a decline in neurocognitive functions, especially memory, attention, and problem-solving. Reduced dopamine concentrations in the prefrontal cortex are thought to contribute to attention deficit disorder. It has been found that D1 receptors are responsible for the cognitive-enhancing effects of dopamine.[7] On the converse, however, anti-psychotic medications act as dopamine antagonists and are used in the treatment of positive symptoms in schizophrenia, although the older, so-called "typical" antipsychotics most commonly act on D2 receptors[8], while the atypical drugs also act on D1, D3 and D4 receptors[9][10].

[edit] Regulating prolactin secretion

Dopamine is the primary neuroendocrine inhibitor of the secretion of prolactin from the anterior pituitary gland. [11] Dopamine produced by neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus is secreted into the hypothalamo-hypophysial blood vessels of the median eminence, which supply the pituitary gland. The lactotrope cells that produce prolactin, in the absence of dopamine, secrete prolactin continuously; dopamine inhibits this secretion. Thus, in the context of regulating prolactin secretion, dopamine is occasionally called prolactin-inhibiting factor (PIF), prolactin-inhibiting hormone (PIH), or prolactostatin. Prolactin also seems to inhibit dopamine release, such as after orgasm, and is chiefly responsible for the refractory period.

[edit] Motivation and pleasure

[edit] Reinforcement

Dopamine is commonly associated with the pleasure system of the brain, providing feelings of enjoyment and reinforcement to motivate a person proactively to perform certain activities. Dopamine is released (particularly in areas such as the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex) by naturally rewarding experiences such as food, sex, drugs, and neutral stimuli that become associated with them. Recent studies indicate that aggression may also stimulate the release of dopamine in this way. This theory is often discussed in terms of drugs such as cocaine, nicotine, and amphetamines, which directly or indirectly lead to an increase of dopamine in the mesolimbic reward pathway of the brain, and in relation to neurobiological theories of chemical addiction, arguing that this dopamine pathway is pathologically altered in addicted persons.[12][13][14]

[edit] Reuptake inhibition, expulsion

Cocaine and amphetamines inhibit the re-uptake of dopamine; however, they influence separate mechanisms of action. Cocaine is a dopamine transporter blocker that competitively inhibits dopamine uptake to increase the lifetime of dopamine and augments an overabundance of dopamine (an increase of up to 150 percent) within the parameters of the dopamine neurotransmitters.

Like cocaine, amphetamines increase the concentration of dopamine in the synaptic gap, but by a different mechanism. Amphetamines are similar in structure to dopamine, and so can enter the terminal button of the presynaptic neuron via its dopamine transporters as well as by diffusing through the neural membrane directly. By entering the presynaptic neuron, amphetamines force dopamine molecules out of their storage vesicles and expel them into the synaptic gap by making the dopamine transporters work in reverse.

[edit] Incentive salience

Dopamine's role in experiencing pleasure has been questioned by several researchers. It has been argued that dopamine is more associated with anticipatory desire and motivation (commonly referred to as "wanting") as opposed to actual consummatory pleasure (commonly referred to as "liking").

[edit] Dopamine, learning, and reward-seeking behavior

Dopaminergic neurons of the midbrain are the main source of dopamine in the brain.[15] Dopamine has been shown to be involved in the control of movements, the signaling of error in prediction of reward, motivation, and cognition. Cerebral dopamine depletion is the hallmark of Parkinson's disease.[15] Other pathological states have also been associated with dopamine dysfunction, such as schizophrenia, autism, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, as well as drug abuse. Dopamine is closely associated with reward-seeking behaviors, such as approach, consumption, and addiction.[15] Recent researches suggest that the firing of dopaminergic neurons is a motivational substance as a consequence of reward-anticipation. This hypothesis is based on the evidence that, when a reward is greater than expected, the firing of certain dopaminergic neurons increases, which consequently increases desire or motivation towards the reward.[15]

[edit] Animal studies

Clues to dopamine's role in motivation, desire, and pleasure have come from studies performed on animals. In one such study, rats were depleted of dopamine by up to 99 percent in the nucleus accumbens and neostriatum using 6-hydroxydopamine.[15] With this large reduction in dopamine, the rats would no longer eat by their own volition. The researchers then force-fed the rats food and noted whether they had the proper facial expressions indicating whether they liked or disliked it. The researchers of this study concluded that the reduction in dopamine did not reduce the rat's consummatory pleasure, only the desire to actually eat. In another study, mutant hyperdopaminergic (increased dopamine) mice show higher "wanting" but not "liking" of sweet rewards.[16]

[edit] The effects of drugs that reduce dopamine levels in humans

In humans, however, drugs that reduce dopamine activity (neuroleptics, e.g. some antipsychotics) have been shown to reduce motivation, and to cause anhedonia a.k.a. the inability to experience pleasure.[17] Selective D2/D3 agonists pramipexole and ropinirole, used to treat Restless legs syndrome, have limited anti-anhedonic properties as measured by the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale.[18] (The Snaith-Hamilton-Pleasure-Scale (SHAPS), introduced in English in 1995, assesses self-reported anhedonia in psychiatric patients.)

[edit] Opioid and cannabinoid transmission

Opioid and cannabinoid transmission instead of dopamine may modulate consummatory pleasure and food palatability (liking).[19] This could explain why animals' "liking" of food is independent of brain dopamine concentration. Other consummatory pleasures, however, may be more associated with dopamine. One study found that both anticipatory and consummatory measures of sexual behavior (male rats) were disrupted by DA receptor antagonists.[20] Libido can be increased by drugs that affect dopamine, but not by drugs that affect opioid peptides or other neurotransmitters.

[edit] Sociability

Sociability is also closely tied to dopamine neurotransmission. Low D2 receptor-binding is found in people with social anxiety. Traits common to negative schizophrenia (social withdrawal, apathy, anhedonia) are thought to be related to a hypodopaminergic state in certain areas of the brain. In instances of bipolar disorder, manic subjects can become hypersocial, as well as hypersexual. This is credited to an increase in dopamine, because mania can be reduced by dopamine-blocking anti-psychotics.[21]

[edit] Processing of pain

Dopamine has been demonstrated to play a role in pain processing in multiple levels of the central nervous system including the spinal cord [22], periaqueductal gray (PAG)[23], thalamus [24], basal ganglia[25] [26] insular cortex [27][28] and cingulate cortex.[29] Accordingly, decreased levels of dopamine have been associated with painful symptoms that frequently occur in Parkinson's disease.[30] Abnormalities in dopaminergic neurotransmission have also been demonstrated in painful clinical conditions, including burning mouth syndrome,[31] fibromyalgia [32] [33] and restless legs syndrome.[34] In general, the analgesic capacity of dopamine occurs as a result of dopamine D2 receptor activation; however, exceptions to this exist in the PAG, in which dopamine D1 receptor activation attenuates pain presumabley via activation of neurons involved in descending inhibition.[35] In addition, D1 receptor activation in the insular cortex appears to attenuate subsequent pain-related behavior.

[edit] Salience

| This section may contain original research or unverified claims. Please improve the article by adding references. See the talk page for details. (February 2009) |

Dopamine may also have a role in the salience ('noticeableness') of perceived objects and events, with potentially important stimuli such as: 1) rewarding things or 2) dangerous or threatening things seeming more noticeable or important.[36] This hypothesis argues that dopamine assists decision-making by influencing the priority, or level of desire, of such stimuli to the person concerned.

One possible mechanism of paranoid thought architecture, both in schizophrenics and in amphetamine abusers (both groups are widely hypothesized to suffer from hyperabundance of dopamine), is as follows: hyperabundance of dopamine causes widespread salience: an impression of significance attendant to statements, events, things, etc. in the immediate environment. This heightened significance can frequently be disturbing since it may have no rational basis. The individual experiencing this heightened significance may attempt to account for it and in this way paranoid ideation begins as a theoretical structure designed to account for this disturbing impressionistic significance.

On this model, the impression of heightened significance ("Meaning beyond meaning" or "things are not as they seem" as Carol North put it[37]) is primary and gives rise to the theoretical efforts - the paranoid ideation. On this model, the paranoid ideation is engendered only indirectly by dopamine surfeit. If we follow this model, what is not clear, however, is the way in which exaggerated salience (supposing this to be a result of dopamine surfeit) gives rise to the sense of pervasive malfeasance which is a hallmark feature of paranoid schizophrenic and amphetamine-psychotic ideation.

This sense of malfeasance need not be a direct product of salience; nor is it necessary that salience be a disquieting experience. It is neither a priori nor a posteriori true that salience leads inevitably to paranoid ideation. And the conviction of malfeasance may indeed have a non-sense-impressionistic source; i.e. there is no apparent reason (other than dogmatism) to follow the dictum that nothing is in the mind that was not first in the world of sense impressions. It may be that suspicion is engendered independently of impressions of salience. However, the two would seem philosophically linked in that it is hard to imagine an object of suspicion which is not also salient. The question then can be renewed: does the salience come first or the suspicion? It could be that they occur together but are distinct.

In the case of paranoid ideation, it does not seem prima facie likely that this thought architecture would spring into existence simply because of salience. The sense of malefic conspiracy (a conspiracy which may be largely impersonal and theological, as in the case of Daniel Paul Schreber)[38] is so consistent in paranoid ideation (of various kinds, in various individuals, of various origins) that it would seem to be a kind of mental capacity unto itself (albeit likely an exaggeration of this capacity, for vigilance or suspicion, e.g.), not something which is a product of a "suspicion-neutral" rational mind working to interpret irrational incidences of salience.

That is, there is no reason to suppose that paranoid suspicion must be engendered by sense data of some kind (even of exaggerated salience) since this arbitrarily treats the suspicion as a learned response to certain sense data, rather than a capacity unto itself. (This would be analogous to treating human aggression as a learned response rather than as an innate capacity.) And indeed there would seem good reason to suppose the existence of an innate capacity for suspicion and vigilance, since these activities would tend toward individual survival.

[edit] Behavior disorders

Deficient dopamine neurotransmission is implicated in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and stimulant medications used to successfully treat the disorder increase dopamine neurotransmission, leading to decreased symptoms.[citation needed]

The long term use of levodopa in Parkinson's disease has been linked to the so-called dopamine dysregulation syndrome.[39]

[edit] Latent inhibition and creative drive

Dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway increases general arousal and goal directed behaviors and decreases latent inhibition; all three effects increase the creative drive of idea generation. This has led to a three-factor model of creativity involving the frontal lobes, the temporal lobes, and mesolimbic dopamine.[40]

[edit] Chemoreceptor trigger zone

Dopamine is one of the neurotransmitters implicated in the control of nausea and vomiting via interactions in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Metoclopramide is a D2-receptor antagonist that functions as a prokinetic/antiemetic.

[edit] Links to psychosis

Abnormally high dopamine action has also been strongly linked to psychosis and schizophrenia,[41] Dopamine neurons in the mesolimbic pathway are particularly associated with these conditions. Evidence comes partly from the discovery of a class of drugs called the phenothiazines (which block D2 dopamine receptors) that can reduce psychotic symptoms, and partly from the finding that drugs such as amphetamine and cocaine (which are known to greatly increase dopamine levels) can cause psychosis.[42] Because of this, most modern antipsychotic medications, for example, Risperidone, are designed to block dopamine function to varying degrees.

[edit] Therapeutic use

Levodopa is a dopamine precursor used in various forms to treat Parkinson's disease and dopa-responsive dystonia. It is typically co-administered with an inhibitor of peripheral decarboxylation (DDC, dopa decarboxylase), such as carbidopa or benserazide. Inhibitors of alternative metabolic route for dopamine by catechol-O-methyl transferase are also used. These include entacapone and tolcapone.

[edit] Peripheral effects

Dopamine also has effects when administered through an IV line outside the CNS. The brand name of this preparation is known as Intropin. The effects in this form are dose dependent.

- Dosages from 2 to 5 μg/kg/min are considered the "renal dose."[citation needed] At this low dosage, dopamine binds D1 receptors, dilating blood vessels, increasing blood flow to renal, mesenteric, and coronary arteries; and increasing overall renal perfusion.[43] Dopamine therefore has a diuretic effect, potentially increasing urine output from 5 ml/kg/hr to 10 ml/kg/hr.[citation needed]

- Intermediate dosages from 5 to 10 μg/kg/min additionally have a positive inotropic and chronotropic effect through increased β1 receptor activation. It is used in patients with shock or heart failure to increase cardiac output and blood pressure.[43] Dopamine begins to affect the heart at the lower doses, from about 3 mcg/kg/min IV.[citation needed]

- High doses from 10 to 20 μg/kg/min is the "pressor" dose.[citation needed] This dose causes vasoconstriction, increases systemic vascular resistance, and increases blood pressure through α1 receptor activation;[43] but can cause the vessels in the kidneys to constrict to the point where they will become non-functional.[citation needed]

[edit] Dopamine and fruit browning

Polyphenol oxidases (PPOs) are a family of enzymes responsible for the browning of fresh fruits and vegetables when they are cut or bruised. These enzymes use molecular oxygen (O2) to oxidise various 1,2-diphenols to their corresponding quinones. The natural substrate for PPOs in bananas is dopamine. The product of their oxidation, dopamine quinone, spontaneously oxidises to other quinones. The quinones then polymerise and condense with amino acids and proteins to form brown pigments known as melanins. The quinones and melanins derived from dopamine may help protect damaged fruit and vegetables against growth of bacteria and fungi.[44]

[edit] References

- ^ http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O87-ventraltegmentalarea.html Reference for VTA.

- ^ Benes, F.M. Carlsson and the discovery of dopamine. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, Volume 22, Issue 1, 1 January 2001, Pages 46-47.

- ^ Fahn, Stanley, "The History of Levodopa as it Pertains to Parkinson’s Disease," Movement Disorder Society’s 10th International Congress of Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders on November 1, 2006, in Kyoto, Japan.

- ^ Peter Redgrave, Kevin Gurney (2006). "The short-latency dopamine signal: a role in discovering novel actions?". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7: 967–975. doi:.

- ^ Barron AB, Maleszka R, Vander Meer RK, Robinson GE (2007). "Octopamine modulates honey bee dance behavior". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (5): 1703–7. doi:. PMID 17237217.

- ^ Schultz, Cambridge university, UK

- ^ Heijtz RD, Kolb B, Forssberg H (2007). "Motor inhibitory role of dopamine D1 receptors: implications for ADHD" (PDF). Physiol Behav 92 (1-2): 155–160. doi:. PMID 17585966. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6T0P-4NTB97R-Y-1&_cdi=4868&_user=308069&_orig=search&_coverDate=09%2F30%2F2007&_sk=999079998&view=c&wchp=dGLbVzz-zSkzV&md5=c49d721e7e713190c2ac6fab7a491093&ie=/sdarticle.pdf.

- ^ http://www.williams.edu/imput/synapse/pages/IIIB5.htm

- ^ http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/181/4/271

- ^ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6T99-3YYTH6C-3P&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=7fda10d8dad0b9937580f6371eebb2d5

- ^ Ben-Jonathan N, Hnasko R (2001). "Dopamine as a Prolactin (PRL) Inhibitor" (PDF). Endocrine Reviews 22 (6): 724–763. doi:. PMID 11739329. http://edrv.endojournals.org/cgi/reprint/22/6/724.pdf.

- ^ Vanderbilt University (2008, January 15). Aggression As Rewarding As Sex, Food And Drugs, New Research Shows. ScienceDaily.

- ^ Giuliano, F.; Allard J. (2001). "Dopamine and male sexual function". Eur Urol 40: 601–608. doi:. PMID 11805404.

- ^ Giuliano, F.; Allard J. (2001). "Dopamine and sexual function". Int J Impot Res 13 (Suppl 3): S18–S28. doi:. PMID 11477488. http://www.nature.com/ijir/journal/v13/n3s/index.html.

- ^ a b c d e Arias-Carrión O, Pöppel E (2007). "Dopamine, learning and reward-seeking behavior". Act Neurobiol Exp 67 (4): 481–488. http://www.ane.pl/pdfdownload.php?art=6738.

- ^ Peciña S, Cagniard B, Berridge K, Aldridge J, Zhuang X (2003). "Hyperdopaminergic mutant mice have higher "wanting" but not "liking" for sweet rewards". J Neurosci 23 (28): 9395–402. PMID 14561867.

- ^ Lambert M, Schimmelmann B, Karow A, Naber D (2003). "Subjective well-being and initial dysphoric reaction under antipsychotic drugs - concepts, measurement and clinical relevance". Pharmacopsychiatry 36 (Suppl 3): S181–90. doi:. PMID 14677077.

- ^ Lemke M, Brecht H, Koester J, Kraus P, Reichmann H (2005). "Anhedonia, depression, and motor functioning in Parkinson's disease during treatment with pramipexole". J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 17 (2): 214–20. doi:. PMID 15939976. http://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/17/2/214.

- ^ Peciña S, Berridge K (2005). "Hedonic hot spot in nucleus accumbens shell: where do mu-opioids cause increased hedonic impact of sweetness?". J Neurosci 25 (50): 11777–86. doi:. PMID 16354936. http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/content/full/jneuro;25/50/11777.

- ^ Pfaus J, Phillips A (1991). "Role of dopamine in anticipatory and consummatory aspects of sexual behavior in the male rat". Behav Neurosci 105 (5): 727–43. doi:. PMID 1840012.

- ^ http://bipolar.about.com/cs/menu_treat/a/0312_treatmania_3.htm

- ^ Jensen TS, Yaksh TL.Effects of an intrathecal dopamine agonist, apomorphine, on thermal and chemical evoked noxious responses in rats.Brain Res. 1984 Apr 2;296(2):285-93

- ^ Flores JA, El Banoua F, Galán-Rodríguez B, Fernandez-Espejo E.Opiate anti-nociception is attenuated following lesion of large dopamine neurons of the periaqueductal grey: critical role for D1 (not D2) dopamine receptors.Pain. 2004 Jul;110(1-2):205-14.

- ^ Shyu BC, Kiritsy-Roy JA, Morrow TJ, Casey KL.Neurophysiological, pharmacological and behavioral evidence for medial thalamic mediation of cocaine-induced dopaminergic analgesia.Brain Res. 1992 Feb 14;572(1-2):216-23.

- ^ Chudler EH, Dong WK.The role of the basal ganglia in nociception and pain.Pain. 1995 Jan;60(1):3-38

- ^ Altier N, Stewart J.The role of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens in analgesia.Life Sci. 1999;65(22):2269-87

- ^ Burkey AR, Carstens E, Jasmin L.Dopamine reuptake inhibition in the rostral agranular insular cortex produces antinociception.J Neurosci. 1999 May 15;19(10):4169-79.

- ^ Coffeen U, López-Avila A, Ortega-Legaspi JM, del Angel R, López-Muñoz FJ, Pellicer F.Dopamine receptors in the anterior insular cortex modulate long-term nociception in the rat.Eur J Pain. 2008 Jul;12(5):535-43.

- ^ López-Avila A, Coffeen U, Ortega-Legaspi JM, del Angel R, Pellicer F.Dopamine and NMDA systems modulate long-term nociception in the rat anterior cingulate cortex.Pain. 2004 Sep;111(1-2):136-43.

- ^ Brefel-Courbon C, Payoux P, Thalamas C, Ory F, Quelven I, Chollet F, Montastruc JL, Rascol O.Effect of levodopa on pain threshold in Parkinson's disease: a clinical and positron emission tomography study.Mov Disord. 2005 Dec;20(12):1557-63.

- ^ Jääskeläinen SK, Rinne JO, Forssell H, Tenovuo O, Kaasinen V, Sonninen P, Bergman J.Role of the dopaminergic system in chronic pain -- a fluorodopa-PET study.Pain. 2001 Feb 15;90(3):257-60.

- ^ Wood PB, Patterson JC 2nd, Sunderland JJ, Tainter KH, Glabus MF, Lilien DL.Reduced presynaptic dopamine activity in fibromyalgia syndrome demonstrated with positron emission tomography: a pilot study.J Pain. 2007 Jan;8(1):51-8.

- ^ Wood PB, Schweinhardt P, Jaeger E, Dagher A, Hakyemez H, Rabiner EA, Bushnell MC, Chizh BA.Fibromyalgia patients show an abnormal dopamine response to pain.Eur J Neurosci. 2007 Jun;25(12):3576-82.

- ^ Cervenka S, Pålhagen SE, Comley RA, Panagiotidis G, Cselényi Z, Matthews JC, Lai RY, Halldin C, Farde L.Support for dopaminergic hypoactivity in restless legs syndrome: a PET study on D2-receptor binding.Brain. 2006 Aug;129(Pt 8):2017-28.

- ^ Wood PB.Role of central dopamine in pain and analgesia.Expert Rev Neurother. 2008 May;8(5):781-97.

- ^ Schultz W (2002). "Getting formal with dopamine and reward". Neuron 36 (2): 241–263. doi:. PMID 12383780.

- ^ Carol North, M.D., Welcome Silence: My Triumph Over Schizophrenia ISBN 0788099272

- ^ Daniel Paul Schreber, Memoirs of My Nervous Illness

- ^ Merims D, Giladi N (2008). "Dopamine dysregulation syndrome, addiction and behavioral changes in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 14 (4): 273–80. doi:. PMID 17988927.

- ^ Flaherty, A.W, (2005). "Frontotemporal and dopaminergic control of idea generation and creative drive". Journal of Comparative Neurology 493 (1): 147–153. doi:. PMID 16254989.

- ^ "Disruption of gene interaction linked to schizophrenia". St. Jude Children's Research Hospital. http://www.innovations-report.com/html/reports/life_sciences/report-52499.html. Retrieved on 2006-07-06.

- ^ Lieberman, J.A.; JM Kane, J. Alvir (1997). "Provocative tests with psychostimulant drugs in schizophrenia". Psychopharmacology (Berl). 91 (4): 415–433. doi:. PMID 2884687. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=pubmed&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=2884687&query_hl=1&itool=pubmed_DocSum. Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ^ a b c Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. pp. 8. ISBN 1-59541-101-1.

- ^ Mayer, AM (2006). "Polyphenol oxidases in plants and fungi: Going places? A review". Phytochemistry 67: 2318–2331. doi:. PMID 16973188.

[edit] See also

- Addiction

- Amphetamine

- Antipsychotic

- Catecholamine

- Catechol-O-methyl transferase

- Classical conditioning

- Operant conditioning

- Cocaine

- Depression

- Dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia

- Dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Methylphenidate

- Neurotransmitter

- Parkinson's disease

- Prolactinoma

- Schizophrenia

- Selegiline

- Serotonin

[edit] External links

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||