Afghanistan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Islamic Republic of Afghanistan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Milli Tharana |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Kabul |

|||||

| Official languages | Dari (Persian), Pashto[1] | |||||

| Demonym | Afghan[alternatives] | |||||

| Government | Islamic republic | |||||

| - | President | Hamid Karzai | ||||

| - | Vice President | Ahmad Zia Massoud | ||||

| - | Vice President | Karim Khalili | ||||

| - | Chief Justice | Abdul Salam Azimi | ||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | First Afghan state[2] | October 1747 | ||||

| - | Independence from the United Kingdom | August 19, 1919 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 647,500 km2 (41st) 251,772 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2008 estimate | 32,738,376 (37th) | ||||

| - | 1979 census | 13,051,358 | ||||

| - | Density | 46/km2 (150th) 119/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $20.099 billion[3] (96th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $733[3] (IMF) (172nd) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $9.596 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $350[3] (IMF) | ||||

| HDI (1993) | 0.229 (n/a) (unranked) | |||||

| Currency | Afghani (AFN) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+4:30) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | (UTC+4:30) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .af | |||||

| Calling code | 93 | |||||

Afghanistan (pronounced /æfˈgænɪstæn/[4]), officially the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country that is located approximately in the center of Asia. It is variously designated as geographically located within Central Asia,[5][6] South Asia,[7][8] and the Middle East.[9] It is bordered by Pakistan in the south and east, Iran in the south and west, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan in the north, and China in the far northeast.

Afghanistan is a crossroads between the East and the West, and has been an ancient focal point of trade and migration. It has an important geostrategical location, connecting South and Central Asia and Middle East. During its long history, the land has seen various invaders and conquerors, while on the other hand, local entities invaded the surrounding vast regions to form their own empires. Ahmad Shah Durrani created the Durrani Empire in 1747, which is considered the beginning of modern Afghanistan.[10] Subsequently, the capital was shifted to Kabul and most of its territories ceded to former neighboring countries. In the late 19th century, Afghanistan became a buffer state in "The Great Game" played between the British Indian Empire and Russian Empire.[11] On August 19, 1919, following the third Anglo-Afghan war, the country regained full independence from the United Kingdom over its foreign affairs.

Since the late 1970s Afghanistan has suffered continuous and brutal civil war in addition to foreign interventions in the form of the 1979 Soviet invasion and the recent 2001 U.S.-led invasion that toppled the Taliban government. In late 2001 the United Nations Security Council authorized the creation of an International Security Assistance Force (ISAF). This force is composed of NATO troops that are involved in assisting the government of President Hamid Karzai in establishing the writ of law as well as rebuilding key infrastructures in the nation. In 2005, the United States and Afghanistan signed a strategic partnership agreement committing both nations to a long-term relationship. In the meantime, multi-billion US dollars have also been provided by the international community for the reconstruction of the country.

Etymology

The name Afghānistān translates to the "Land of Afghans". Its modern usage derives from the word Afghan.

Origin of the name

The first part of the name, "Afghan", is an alternative name for the Pashtuns who are the founders and the largest ethnic group of the country. They probably began using the term Afghan as a name for themselves since at least the Islamic period and onwards. According to W. K. Frazier Tyler, M. C. Gillet and several other scholars, "The word Afghan first appears in history in the Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam in 982 AD." Al-Biruni referred to Afghans as various tribes living on the western frontier mountains of the Indus River, which would be the Sulaiman Mountains.[12]

A Moroccan traveller, Ibn Battuta, visiting Kabul in 1333 writes:[13]

We travelled on to Kabul, formerly a vast town, the site of which is now occupied by a village inhabited by a tribe of Persians called Afghans.

In this regard the Encyclopædia Iranica states:[14]

From a more limited, ethnological point of view, "Afghān" is the term by which the Persian-speakers of Afghanistan (and the non-Paštō-speaking ethnic groups generally) designate the Paštūn. The equation [of] Afghan [and] Paštūn has been propagated all the more, both in and beyond Afghanistan, because the Paštūn tribal confederation is by far the most important in the country, numerically and politically.

It further explains:

The term "Afghān" has probably designated the Paštūn since ancient times. Under the form Avagānā, this ethnic group is first mentioned by the Indian astronomer Varāha Mihira in the beginning of the 6th century CE in his Brihat-samhita.

This information is supported by traditional Pashto literature, for example, in the writings of the 17th-century Pashto poet Khushal Khan Khattak:[15]

Pull out your sword and slay any one, that says Pashtun and Afghan are not one! Arabs know this and so do Romans: Afghans are Pashtuns, Pashtuns are Afghans!

The last part of the name, -stān is an ancient Indo-Iranian suffix for "place", prominent in many languages of the region.

The term "Afghanistan," meaning the "Land of Afghans," was mentioned by the sixteenth century Mughal Emperor Babur in his memoirs, referring to the territories south of Kabul that were inhabited by Pashtuns (called "Afghans" by Babur).[16]

Until the 19th century the name was only used for the traditional lands of the Pashtuns, while the kingdom as a whole was known as the Kingdom of Kabul, as mentioned by the British statesman and historian Mountstuart Elphinstone.[17] Other parts of the country were at certain periods recognized as independent kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of Balkh in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[18]

With the expansion and centralization of the country, Afghan authorities adopted and extended the name "Afghanistan" to the entire kingdom, after its English translation had already appeared in various treaties between the British Raj and Qajarid Persia, referring to the lands subject to the Pashtun Barakzai Dynasty of Kabul.[19] "Afghanistan" as the name for the entire kingdom was mentioned in 1857 by Friedrich Engels.[20] It became the official name when the country was recognized by the world community in 1919, after regaining full independence over its foreign affairs from the British,[21] and was confirmed as such in the nation's 1923 constitution.[22]

Geography

Afghanistan is a landlocked and mountainous country in South-Central Asia, with plains in the north and southwest. The highest point is Nowshak, at 7,485 m (24,557 ft) above sea level. Large parts of the country are dry, and fresh water supplies are limited. The endorheic Sistan Basin is one of the driest regions in the world.[23] Afghanistan has a continental climate with hot summers and cold winters. The country is frequently subject to minor earthquakes, mainly in the northeast of Hindu Kush mountain areas. Some 125 villages were damaged and 4000 people killed by the May 30, 1998 earthquake.

At 249,984 sq mi (647,500 km²), Afghanistan is the world's 41st-largest country (after Myanmar).

Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan border Afghanistan to the north, Iran to the west, Pakistan to the south and the People's Republic of China to the east.

The country's natural resources include gold, silver, copper, zinc and iron ore in southeastern areas; precious and semi-precious stones such as lapis, emerald and azure in the north-east; and potentially significant petroleum and natural gas reserves in the north. The country also has uranium, coal, chromite, talc, barites, sulfur, lead, and salt.[1][24][25][26] However, these significant mineral and energy resources remain largely untapped due to the effects of the Soviet invasion and the subsequent civil war. Plans are underway to begin extracting them in the near future.[27][28]

History

Though the modern state of Afghanistan was founded or created in 1747 by Ahmad Shah Durrani[10], the land has an ancient history and various timelines of different civilizations. Excavation of prehistoric sites by Louis Dupree, the University of Pennsylvania, the Smithsonian Institution and others suggests that humans were living in what is now Afghanistan at least 50,000 years ago, and that farming communities of the area were among the earliest in the world.[29][30]

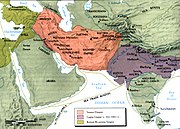

Afghanistan is a country at a unique nexus point where numerous Indo-European civilizations have interacted and often fought, and was an important site of early historical activity. Through the ages, the region has been home to various people, among them the Aryan (Indo-Iranian) tribes, such as the Kambojas, Bactrians, Pashtuns, etc. It also has been conquered by a host of people, including the Median and Persian Empires, Alexander the Great, the Seleucids, the Indo-Greeks, Turks, and Mongols. In recent times, invasions from the British, Soviets, and most recently by the United States and their allies have taken place. On the other hand, native entities have invaded surrounding regions in Iranian plateau, Central Asia and Indian subcontinent to form empires of their own.

In 2000 BC, Indo-European-speaking Aryans are thought to have been in the region of Afghanistan. It is unlikely[31] that the Aryans themselves originated in Afghanistan although they did migrate from there south towards India and west towards Persia, but they also migrated into Europe via north of the Caspian. These Aryans set up a nation which became known as Airyānem Vāejah. Original homelands of the Aryans have been proposed as Anatolia, Kurdistan, Central Asia, Iran, or Northern India, with the directions of the historical migration varying accordingly.[32][33] Later, during the rule of Ashkanian, Sasanian and after, it was called Erānshahr (Persian: ايرانشهر - Īrānšahr) meaning “Dominion of the Aryans”.

It has been speculated that Zoroastrianism might have originated in what is now Afghanistan between 1800 to 800 BC, as Zoroaster lived and died in Balkh.[34][35] Ancient Eastern Iranian languages, such as Avestan, may have been spoken in this region around the time of the rise of Zoroastrianism. By the middle of the sixth century BC, the Persian Empire of the Achaemenid Persians overthrew the Median Empire and incorporated Afghanistan (known as Arachosia to the Greeks) within its boundaries. Alexander the Great conquered Afghanistan after 330 BCE. Following Alexander's brief occupation, the successor state of the Seleucid Empire controlled the area until 305 BCE, when they gave most of the area to the Mauryan Empire as part of an alliance treaty. During Mauryan rule, Buddhism became the dominant religion in the region. The Mauryans were overthrown by the Sunga Dynasty in 185 BCE, leading to the Hellenistic reconquest of Afghanistan by the Greco-Bactrians by 180 BCE. Much of Afghanistan soon broke away from the Greco-Bactrians and became part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The Indo-Greeks were defeated by the Indo-Scythians and expelled from most of Afghanistan by the end of the 2nd century BCE.

During the first century, the Parthian Empire subjugated Afghanistan, but lost it to their Indo-Parthian vassals. In the mid to late 1st century AD the vast Kushan Empire, centered in modern Afghanistan, became great patrons of Buddhist culture. The Kushans were defeated by the Sassanids in the third century. Although various rulers calling themselves Kushanshas (generally known as Indo-Sassanids) continued to rule at least parts of the region, they were probably more or less subject to the Sassanids.[36] The late Kushans were followed by the Kidarite Huns[37] who, in turn, were replaced by the short-lived but powerful Hephthalites, as rulers of the region in the first half of the fifth century.[38] The Hephthalites were defeated by the Sasanian king Khosrau I in AD 557, who re-established Sassanid power in Persia. However, the successors of Kushans and Hepthalites established a small dynasty in Kabulistan called Kushano-Hephthalites or Kabul-Shahan/Shahi, who were later defeated by the Muslim Arab armies and finally conquered by Muslim Turkish armies led by the Ghaznavids.

Islamic and Mongol conquests of the region

In the Middle Ages, up to the nineteenth century, Afghanistan was part of a larger region known as Greater Khorasan.[39][40][41] Several important centers of Khorāsān are thus located in modern Afghanistan, such as Balkh, Herat, Ghazni and Kabul. It was during this period of time when Islam was introduced and spread in the area.

The region of Afghanistan became the center of various important empires, including that of the Samanids (875–999), Ghaznavids (977–1187), Seljukids (1037–1194), Ghurids (1149–1212), Mongol Empire, Ilkhanate (1225–1335), and Timurids (1370–1506). Among them, the periods of the Ghaznavids[42] and Timurids[43] are considered as some of the most brilliant eras of the region's history.

In 1219 the region was overrun by the Mongols under Genghis Khan, who devastated the land. Their rule continued with the Ilkhanate [one of 4 Subordinate Mongolian Khanates], and was extended further following the invasion of Timur Lang (“Tamerlane”), a ruler from Central Asia. In 1504, Babur, a descendant of both Timur Lang and Genghis Khan, established the Mughal Empire with its capital at Kabul. By the early 1700s, Afghanistan was controlled by several ruling groups: Uzbeks to the north, Safavids to the west and the remaining larger area by the Mughals or self-ruled by local tribes.

Hotaki dynasty

In 1709, Mir Wais Hotak, a local Afghan (Pashtun) from the Ghilzai clan, overthrew and killed Gurgin Khan, the Safavid governor of Kandahar. Mir Wais successfully defeated the Persians, who were attempting to convert the local population of Kandahar from Sunni to the Shia sect of Islam. Mir Wais held the region of Kandahar until his death in 1715 and was succeeded by his son Mir Mahmud Hotaki. In 1722, Mir Mahmud led an Afghan army to Isfahan (Iran), sacked the city and proclaimed himself King of Persia. However, the great majority still rejected the Afghan regime as usurping, and after the massacre of thousands of civilians in Isfahan by the Afghans – including more than three thousand religious scholars, nobles, and members of the Safavid family – the Hotaki dynasty was eventually removed from power by a new ruler, Nadir Shah of Persia.[44][45]

Durrani Empire: beginnings of the “Afghan state”

In 1738 Nadir Shah and his army, which included four thousand Pashtuns of the Abdali clan[46], conquered the region of Kandahar; in the same year he occupied Ghazni, Kabul and Lahore. On June 19, 1747, Nadir Shah was assassinated, possibly planned by his nephew Ali Qoli. In the same year, one of Nadir's military commanders and personal bodyguard, Ahmad Shah Abdali, a Pashtun from the Abdali clan, called for a loya jirga following Nadir's death. The Afghans gathered at Kandahar and chose Ahmad Shah as their King. Since then, he is often regarded as the founder of modern Afghanistan.[1][47][48] After the inauguration, he changed his title or clans' name to “Durrani”, which derives from the Persian word Durr, meaning “Pearl”.[46]

By 1751 Ahmad Shah Durrani and his Afghan army conquered the entire present-day Afghanistan, Pakistan, Khorasan and Kohistan provinces of Iran, along with Delhi in India.[20] In October 1772, Ahmad Shah retired to his home in Maruf, Kandahar, where he died peacefully. He was succeeded by his son, Timur Shah Durrani, who transferred the capital from Kandahar to Kabul. Timur died in 1793 and was finally succeeded by his son Zaman Shah Durrani.

European influence and the creation of the state of Afghanistan

During the nineteenth century, following the Anglo-Afghan wars (fought 1839–42, 1878–80, and lastly in 1919) and the ascension of the Barakzai dynasty, Afghanistan saw much of its territory and autonomy ceded to the United Kingdom. The UK exercised a great deal of influence, and it was not until King Amanullah Khan acceded to the throne in 1919 that Afghanistan re-gained complete independence over its foreign affairs (see “The Great Game”). During the period of British intervention in Afghanistan, ethnic Pashtun territories were divided by the Durand Line. This would lead to strained relations between Afghanistan and British India – and later the new state of Pakistan – over what came to be known as the Pashtunistan debate.

The Kingdom of Afghanistan

King Amanullah (1919-1929) moved to end his country's traditional isolation in the years following the Third Anglo-Afghan war. He established diplomatic relations with most major countries and, following a 1927 tour of Europe and Turkey (during which he noted the modernization and secularization advanced by Atatürk), introduced several reforms intended to modernize Afghanistan. A key force behind these reforms was Mahmud Tarzi, Amanullah Khan's Foreign Minister and father-in-law - and an ardent supporter of the education of women. He fought for Article 68 of Afghanistan's first constitution (declared through a Loya Jirga), which made elementary education compulsory.[49] Some of the reforms that were actually put in place, such as the abolition of the traditional Muslim veil for women and the opening of a number of co-educational schools, quickly alienated many tribal and religious leaders. Faced with overwhelming armed opposition, Amanullah was forced to abdicate in January 1929 after Kabul fell to forces led by Habibullah Kalakani.

Prince Mohammed Nadir Khan, a cousin of Amanullah's, in turn defeated and killed Habibullah Kalakani in October of the same year, and with considerable Pashtun tribal support he was declared King Nadir Shah. He began consolidating power and regenerating the country. He abandoned the reforms of Amanullah Khan in favour of a more gradual approach to modernisation. In 1933, however, he was assassinated in a revenge killing by a Kabul student.

Mohammad Zahir Shah, Nadir Khan's 19-year-old son, succeeded to the throne and reigned from 1933 to 1973. The longest period of stability in Afghanistan was when the country was under the rule of King Zahir Shah. Until 1946 Zahir Shah ruled with the assistance of his uncle, who held the post of Prime Minister and continued the policies of Nadir Shah. In 1946, another of Zahir Shah's uncles, Sardar Shah Mahmud Khan, became Prime Minister and began an experiment allowing greater political freedom, but reversed the policy when it went further than he expected. In 1953, he was replaced as Prime Minister by Mohammed Daoud Khan, the king's cousin and brother-in-law. Daoud sought a closer relationship with the Soviet Union and a more distant one towards Pakistan.

Republic of Afghanistan

However, in 1973, Zahir Shah's brother-in-law, Mohammed Daoud Khan, launched a bloodless coup and became the first President of Afghanistan while Zahir Shah was on an official overseas visit. Mohammed Daoud Khan jammed Afghan radio's with anti-Pakistani broadcasts and looked to the Soviet Union and the United States for aid for development.

In 1978 a prominent member of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Mir Akbar Khyber (or “Kaibar”), was killed by the government. The leaders of PDPA apparently feared that Daoud was planning to exterminate them all, especially since most of them were arrested by the government shortly after. Hafizullah Amin and a number of military wing officers of the PDPA managed to remain at large and organised an uprising.

The PDPA, led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, Babrak Karmal and Amin overthrew the regime of Mohammad Daoud, who was killed along with his family. The uprising was known as the Khalq, or Great Saur Revolution ('Saur' means 'April' in Pashto). On May 1, Taraki became President, Prime Minister and General Secretary of the PDPA. The country was then renamed the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), and the PDPA regime lasted, in some form or another, until April 1992.

Some are of the opinion that the 1978 Khalq uprising against the government of Daoud Khan was essentially a resurgence by the Ghilzai tribe of the Pashtun against the Durrani (the tribe of Daoud Khan and the previous monarchy).[50]

Once in power, the PDPA moved to permit freedom of religion and carried out an ambitious land reform, waiving farmers' debts countrywide. They also made a number of statements on women’s rights and introduced women to political life. A prominent example was Anahita Ratebzad, who was a major Marxist leader and a member of the Revolutionary Council. Ratebzad wrote the famous May 28, 1978 New Kabul Times editorial which declared: “Privileges which women, by right, must have are equal education, job security, health services, and free time to rear a healthy generation for building the future of the country … Educating and enlightening women is now the subject of close government attention.”[51]

Many people in the cities including Kabul either welcomed or were ambivalent to these policies. However, the secular nature of the government made it unpopular with religiously conservative Afghans in the villages and the countryside, who favoured traditionalist 'Islamic' law.

The U.S. saw the situation as a prime opportunity to weaken the Soviet Union. As part of a Cold War strategy, in 1979 the United States government (under President Jimmy Carter) began to covertly fund forces ranged against the pro-Soviet government, although warned that this might prompt a Soviet intervention, (according to National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski).[52] The Mujahideen belonged to various different factions, but all shared, to varying degrees, a similarly conservative 'Islamic' ideology.

In March 1979 Hafizullah Amin took over as prime minister, retaining the position of field marshal and becoming vice-president of the Supreme Defence Council. Taraki remained President and in control of the Army. On September 14, Amin overthrew Taraki, who died or was killed.

Soviet invasion and civil war

In order to bolster the Parcham faction, the Soviet Union—citing the 1978 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Good Neighborliness that had been signed between the two countries—intervened on December 24, 1979. Over 100,000 Soviet troops took part in the invasion backed by another 100,000 plus and by members of the Parcham faction. Amin was killed and replaced by Babrak Karmal.

In response to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and part of its overall Cold War strategy, the United States responded by arming and otherwise supporting the Afghan mujahideen, which had taken up arms against the Soviet occupiers. U.S. support began during the Carter administration, but increased substantially during the Reagan administration, in which it became a centerpiece of the so-called Reagan Doctrine under which the U.S. provided support to anti-communist resistance movements in Afghanistan and also in Angola, Nicaragua, and other nations. In addition to U.S. support, the mujahideen received support from Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and other nations.

The Soviet occupation resulted in the killings of at least 600,000 to 2 million Afghan civilians. Over five million Afghans fled their country to Pakistan, Iran and other parts of the world. Faced with mounting international pressure and great number of casualties on both sides, the Soviets withdrew in 1989.

The Soviet withdrawal from the DRA was seen as an ideological victory in the U.S., which had backed the Mujahideen through three U.S. presidential administrations in order to counter Soviet influence in the vicinity of the oil-rich Persian Gulf.

Following the removal of the Soviet forces, the U.S. and its allies lost interest in Afghanistan and did little to help rebuild the war-ravaged country or influence events there.[citation needed] The USSR continued to support President Mohammad Najibullah (former head of the Afghan secret service, KHAD) until 1992 when the new Russian government refused to sell oil products to the Najibullah regime.[53]

Because of the fighting, a number of elites and intellectuals fled to take refuge abroad. This led to a leadership imbalance in Afghanistan. Fighting continued among the victorious Mujahideen factions, which gave rise to a state of warlordism. The most serious fighting during this period occurred in 1994, when over 10,000 people were killed in Kabul alone. It was at this time that the Taliban developed as a politico-religious force, eventually seizing Kabul in 1996 and establishing the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. By the end of 2000 the Taliban had captured 95% of the country.

During the Taliban's seven-year rule, much of the population experienced restrictions on their freedom and violations of their human rights. Women were banned from jobs, girls forbidden to attend schools or universities.[54] Communists were systematically eradicated and thieves were punished by amputating one of their hands or feet.[55] The majority of the opium production was eradicated by 2001.[56]

2001–present war in Afghanistan

Following the September 11 attacks the United States launched Operation Enduring Freedom, a military campaign to destroy the al-Qaeda terrorist training camps inside Afghanistan. The U.S. military also threatened to overthrow the Taliban government for refusing to hand over Osama bin Laden and several al-Qaida members. The U.S. made a common cause with the former Afghan Mujahideen to achieve its ends, including the Northern Alliance, a militia still recognized by the United Nations as the Afghan government.

In late 2001, the United States sent teams of CIA Paramilitary Officers from their Special Activities Division and U.S. Army Special Forces to invade Afghanistan to aid anti-Taliban militias, backed by U.S. air strikes against Taliban and Al Qaeda targets, culminating in the seizure of Kabul by the Northern Alliance and the overthrow of the Taliban, with many local warlords switching allegiance from the Taliban to the Northern Alliance.[57]

In December of the same year, leaders of the former Afghan mujahideen and diaspora met in Germany, and agreed on a plan for the formulation of a new democratic government that resulted in the inauguration of Hamid Karzai, an ethnic Pashtun of the Durrani clan (from which the royal family was drawn) from the southern city of Kandahar, as Chairman of the Afghan Interim Authority.

After a nationwide Loya Jirga in 2002, Karzai was chosen by the representatives to assume the title as Interim President of Afghanistan. The country convened a Constitutional Loya Jirga (Council of Elders) in 2003 and a new constitution was ratified in January 2004. Following an election in October 2004, Hamid Karzai won and became the President of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. Legislative elections were held in September 2005. The National Assembly – the first freely elected legislature in Afghanistan since 1973 – sat in December 2005, and was noteworthy for the inclusion of women as voters, candidates, and elected members.

As the country continues to rebuild and recover, it is still struggling against poverty, poor infrastructure, large concentration of land mines and other unexploded ordnance, as well as a huge illegal poppy cultivation and opium trade. Afghanistan also remains subject to occasionally violent political jockeying. The country continues to grapple with the Taliban insurgency and the threat of attacks from a few remaining al Qaeda.

At the start of 2007 reports of the Taliban's increasing presence in Afghanistan led the U.S. to consider longer tours of duty and even an increase in troop numbers. According to a report filed by Robert Burns of Associated Press on January 16, 2007, “U.S. military officials cited new evidence that the Pakistani military, which has long-standing ties to the Taliban movement, has turned a blind eye to the incursions.” Also, “The number of insurgent attacks is up 300 percent since September, 2006, when the Pakistani government put into effect a peace arrangement with tribal leaders in the north Waziristan area, along Afghanistan's eastern border, a U.S. military intelligence officer told reporters.”

Government and politics

Politics in Afghanistan has historically consisted of power struggles, bloody coups and unstable transfers of power. With the exception of a military junta, the country has been governed by nearly every system of government over the past century, including a monarchy, republic, theocracy and communist state. The constitution ratified by the 2003 Loya jirga restructured the government as an Islamic republic consisting of three branches, (executive, legislature and judiciary).

Afghanistan is currently led by President Hamid Karzai, who was elected in October 2004. The current parliament was elected in 2005. Among the elected officials were former mujahadeen, Taliban members, communists, reformists, and Islamic fundamentalists. 28% of the delegates elected were women, three points more than the 25% minimum guaranteed under the constitution. This made Afghanistan, long known under the Taliban for its oppression of women, one of the leading countries in terms of female representation. Construction for a new parliament building began on August 29, 2005.

The Supreme Court of Afghanistan is currently led by Chief Justice Abdul Salam Azimi, a former university professor who had been legal advisor to the president.[58] The previous court, appointed during the time of the interim government, had been dominated by fundamentalist religious figures, including Chief Justice Faisal Ahmad Shinwari. The court issued several rulings, such as banning cable television, seeking to ban a candidate in the 2004 presidential election and limiting the rights of women, as well as overstepping its constitutional authority by issuing rulings on subjects not yet brought before the court. The current court is seen as more moderate and led by more technocrats than the previous court, although it has yet to issue any rulings.

Law enforcement and military

Afghanistan currently has more than 70,000 national police officers, with plans to recruit more so that the total number can reach 80,000. They are being trained by and through the Afghanistan Police Program. Although the police officially are responsible for maintaining civil order, sometimes local and regional military commanders continue to exercise control in the hinterland. Police have been accused of improper treatment and detention of prisoners. In 2003 the mandate of the International Security Assistance Force, now under command of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was extended and expanded beyond the Kabul area. However, in some areas unoccupied by those forces, local militias maintain control. In many areas, crimes have gone uninvestigated because of insufficient police and/or communications. Troops of the Afghan National Army have been sent to quell fighting in some regions lacking police protection.[59]

The Afghan National Army currently has 80,000 troops, with plans to nearly double in the next few years. The Afghan Army is not affected by corruption as the National Police due to international oversight.

Administrative divisions

Afghanistan is administratively divided into thirty-four (34) provinces (welayats), and for each province there is a capital. Each province is then divided into many provincial districts, and each district normally covers a city or several townships.

The Governor of the province is appointed by the Ministry of Interior, and the Prefects for the districts of the province will be appointed by the provincial Governor. The Governor is the representative of the central government of Afghanistan, and is responsible for all administrative and formal issues. The provincial Chief of Police is appointed by the Ministry of Interior, who works together with the Governor on law enforcement for all the cities or districts of that province.

There is an exception in the capital city (Kabul) where the Mayor is selected by the President of Afghanistan, and is completely independent from the prefecture of the Kabul Province.

Foreign relations

Afghanistan's government is currently fighting an insurgency with the assistance of the United States and NATO. Therefore, relations between Afghanistan and NATO members is strong. Afghanistan depends a lot on multi-billion dollar aid infusions from the United States. Canada, France, the United Kingdom, Australia and Germany are also large donors.

Relations between Afghanistan and the Islamic Republic of Iran are very strong. The two nations share the same language and culture, and both countries are part of Greater Persia. Shiites and Sunnis get a long well in Afghanistan which causes no religious tensions between the two nations. Iran is a consistent donor towards Afghan reconstruction.

Afghan and Pakistani relations always fluctuate. The two nations are always disputing, but recent relations have deteriorated vastly. Afghan Intelligence and American agencies accuse Pakistan of working to stop Afghan reconstruction mainly through the Inter-Services Intelligence. Most of the Taliban come from Pakistan and Osama bin Laden is thought to be hiding in Pakistan. Afghanistan and Pakistan recently fought a series of border skirmishes and the US has lead several air strikes in Pakistani territory from Afghan air bases.

Afghanistan maintains excellent relations with their Northern Allies, including Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan as all three share a similar culture as the Afghans. Hazaras are from those nations.

Afghanistan also has good relations with Russia and India. India is a leading investor in Afghanistan, alongside Iran, and the current Afghan President, Hamid Karzai received some of his college education in India.

Afghanistan has excellent relations with the rest of the Arab and Muslim world. Afghanistan has no relations with Israel and alongside ally Iran, is a frequent non-Arab critic of Israel.

Demographics

A July 2008 estimate of the total Afghan population is 32,738,376.[60]

Largest cities

The only city in Afghanistan with over one million residents is its capital, Kabul. The other major cities in the country are, in order of population size, Herat, Kandahar, Mazar-e Sharif, Jalalabad, Ghazni and Kunduz.

Ethnic groups

The population of Afghanistan is divided into a wide variety of ethnic groups. Because a systematic census has not been held in the country in decades, exact figures about the size and composition of the various ethnic groups are not available.[61] Therefore most figures are approximations only:

|

(1) Based on official census numbers from the 1960s to the 1980s, as well as information found in mainly scholarly sources, the Encyclopædia Iranica[62] gives the following list: |

(2) An approximate distribution of ethnic groups based on the CIA World Factbook[1] is as following:

|

|

|

(3) According to a representative survey, named "A survey of the Afghan people - Afghanistan in 2006", a combined project of The Asia Foundation, the Indian Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) and the Afghan Center for Socio-economic and Opinion Research (ACSOR), the distribution of the ethnic groups is:[63]

|

(4) According to another representative survey, named "Afghanistan: Where Things Stand", a combined effort by the American broadcasting channel ABC News, the British BBC, and the German ARD (from the years 2004 to 2009), and released on February 9th 2009, the ethnic composition of the country is (average numbers):[64]

|

|

Languages

The most common languages spoken in Afghanistan are Eastern Persian (also known as Dari; roughly 50%) and Pashto (roughly 35%). Both are Indo-European languages from the Iranian languages sub-family, and the official languages of the country. Hazaragi, spoken by the Hazara minority, is a distinct dialect of Persian. Other languages spoken include the Turkic languages Uzbek and Turkmen (ca. 9% combined), as well as 30 minor languages, primarily Balochi, Nuristani, Pashai, Brahui, Pamiri languages, Hindko, etc. (ca. 4% combined). Bilingualism is common.

According to the Encyclopædia Iranica,[65] the Persian language is the most widely used language of the country, spoken by around 80% of the population, while Pashto is spoken and understood by around 50% of the population. According to "A survey of the Afghan people - Afghanistan in 2006",[63] Persian is the first language of 49% of the population, while additional 37% speak the language as a second language (combined 86%). Pashto is the first language of 40% of the population, while additional 27% know the language (combined 67%). Uzbek is spoken or understood by 6% of the population, Turkmen by 3%. According to the survey "Afghanistan: Where Things Stand" (avarege numbers from 2005-2009), 69% of the interviewed people preferred Persian, while 31% spoke Pashto.[64]

Culture

Afghans display pride in their religion, country, ancestry, and above all, their independence. Like other highlanders, Afghans are regarded with mingled apprehension and condescension, for their high regard for personal honor, for their clan loyalty and for their readiness to carry and use arms to settle disputes.[66] As clan warfare and internecine feuding has been one of their chief occupations since time immemorial, this individualistic trait has made it difficult for foreign invaders to hold the region.

Afghanistan has a complex history that has survived either in its current cultures or in the form of various languages and monuments. However, many of the country's historic monuments have been damaged in recent wars[67]. The two famous statues of Buddha in the Bamyan Province were destroyed by the Taliban, who regarded them as idolatrous. Other famous sites include the cities of Kandahar, Heart, Ghazni and Balkh. The Minaret of Jam, in the Hari River valley, is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The cloak worn by Muhammad is stored inside the famous Khalka Sharifa in Kandahar City.

Buzkashi is a national sport in Afghanistan. It is similar to polo and played by horsemen in two teams, each trying to grab and hold a goat carcass. Afghan hounds (a type of running dog) also originated in Afghanistan.

Although literacy levels are very low, classic Persian poetry plays a very important role in the Afghan culture. Poetry has always been one of the major educational pillars in Iran and Afghanistan, to the level that it has integrated itself into culture. Persian culture has, and continues to, exert a great influence over Afghan culture. Private poetry competition events known as “musha’era” are quite common even among ordinary people. Almost every homeowner owns one or more poetry collections of some sort, even if they are not read often.

The eastern dialects of the Persian language are popularly known as "Dari". The name itself derives from "Pārsī-e Darbārī", meaning Persian of the royal courts. The ancient term Darī – one of the original names of the Persian language – was revived in the Afghan constitution of 1964, and was intended "to signify that Afghans consider their country the cradle of the language. Hence, the name Fārsī, the language of Fārs, is strictly avoided."[68]

Many of the famous Persian poets of the tenth to fifteenth centuries stem from Khorasan where is now known as Afghanistan. They were mostly also scholars in many disciplines like languages, natural sciences, medicine, religion and astronomy.

- Mawlānā Rumi, who was born and educated in Balkh in the thirteenth century and moved to Konya in modern-day Turkey

- Rabi'a Balkhi (the first poetess in the History of Persian Poetry, tenth century, native of Balkh)

- Daqiqi Balkhi (tenth century, native of Balkh)

- Farrukhi Sistani (tenth century, the Ghaznavids royal poet)

- Unsuri Balkhi (a tenth/eleventh century poet, native of Balkh)

- Khwaja Abdullah Ansari (eleventh century, from Herat)

- Nasir Khusraw (eleventh century, from Qubadyan near Balkh)

- Anvari (twelfth century, lived and died in Balkh)

- Sanā'ī Ghaznawi (twelfth century, native of Ghazni)

- Jāmī of Herāt (fifteenth century, native of Herat in western Afghanistan), and his nephew Abdullah Hatifi Herawi, a well-known poet

- Alī Sher Navā'ī (fifteenth century, Herat).

Most of these individuals were of Persian (Tājīk) ethnicity who still form the second-largest ethnic group in Afghanistan. Also, some of the contemporary Persian language poets and writers, who are relatively well-known in Persian-speaking world, include Khalilullah Khalili,[69] Sufi Ghulam Nabi Ashqari,[70] Sarwar Joya, Parwin Pazwak and others. In 2003, Khaled Hosseini published The Kite Runner which though fiction, captured much of the history, politics and culture experienced in Afghanistan from the 1930s to present day.

In addition to poets and authors, numerous Persian scientists were born or worked in the region of present-day Afghanistan. Most notable was Avicenna (Abu Alī Hussein ibn Sīnā) whose father hailed from Balkh. Ibn Sīnā, who travelled to Isfahan later in life to establish a medical school there, is known by some scholars as "the father of modern medicine". George Sarton called ibn Sīnā "the most famous scientist of Islam and one of the most famous of all races, places, and times." His most famous works are The Book of Healing and The Canon of Medicine, also known as the Qanun. Ibn Sīnā's story even found way to the contemporary English literature through Noah Gordon's The Physician, now published in many languages. Moreover, according to Ibn al-Nadim, Al-Farabi, a well-known philosopher and scientist, was from the Faryab Province of Afghanistan.

Before the Taliban gained power, the city of Kabul was home to many musicians who were masters of both traditional and modern Afghan music, especially during the Nauroz-celebration. Kabul in the middle part of the twentieth century has been likened to Vienna during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The tribal system, which orders the life of most people outside metropolitan areas, is potent in political terms. Men feel a fierce loyalty to their own tribe, such that, if called upon, they would assemble in arms under the tribal chiefs and local clan leaders. In theory, under Islamic law, every believer has an obligation to bear arms at the ruler's call.

Heathcote considers the tribal system to be the best way of organizing large groups of people in a country that is geographically difficult, and in a society that, from a materialistic point of view, has an uncomplicated lifestyle.[66]

Religions

Religiously, Afghans are over 99% Muslims: approximately 74-80% Sunni and 19-25% Shi'a[1][71][72] (estimates vary). Up until the mid-1980s, there were about 30,000 to 150,000 Hindus and Sikhs living in different cities, mostly in Jalalabad, Kabul, and Kandahar.[73][74]

There was a small Jewish community in Afghanistan (see Bukharan Jews) who fled the country after the 1979 Soviet invasion, and only one individual, Zablon Simintov, remains today.[75]

Economy

Afghanistan is a member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC). It is an impoverished country, one of the world's poorest and least developed. Two-thirds of the population lives on fewer than 2 US dollars a day. Its economy has suffered greatly from the 1979 Soviet invasion and subsequent conflicts, while severe drought added to the nation's difficulties in 1998–2001.[76][77]

The economically active population in 2002 was about 11 million (out of a total of an estimated 29 million). As of 2005, the official unemployment rate is at 40%.[78] The number of non-skilled young people is estimated at 3 million, which is likely to increase by some 300,000 per annum.[79]

The nation's economy began to improve since 2002 due to the infusion of multi-billion US dollars in international assistance and investments, as well as remittances from expats.[80] It is also due to dramatic improvements in agricultural production and the end of a four-year drought in most of the country.

The real value of non-drug GDP increased by 29% in 2002, 16% in 2003, 8% in 2004 and 14% in 2005.[81] As much as one-third of Afghanistan's GDP comes from growing poppy and illicit drugs including opium and its two derivatives, morphine and heroin, as well as hashish production.[1] Opium production in Afghanistan has soared to a new record in 2007, with an increase on last year of more than a third, the United Nations has said.[82] Some 3.3 million Afghans are now involved in producing opium.[83] In a recent article in the Washington Quarterly, Peter van Ham and Jorrit Kamminga argue that the international community should establish a pilot project and investigate a licensing scheme to start the production of medicines such as morphine and codeine from poppy crops to help it escape the economic dependence on opium:[84]

According to a 2004 report by the Asian Development Bank, the present reconstruction effort is two-pronged: first it focuses on rebuilding critical physical infrastructure, and second, on building modern public sector institutions from the remnants of Soviet style planning to ones that promote market-led development.[79] In 2006, two U.S. companies, Black & Veatch and the Louis Berger Group, have won a US 1.4 billion dollar contract to rebuild roads, power lines and water supply systems of Afghanistan.[85]

One of the main drivers for the current economic recovery is the return of over 4 million refugees from neighbouring countries and the West, who brought with them fresh energy, entrepreneurship and wealth-creating skills as well as much needed funds to start up businesses. What is also helping is the estimated US 2–3 billion dollars in international assistance every year, the partial recovery of the agricultural sector, and the reestablishment of market institutions. Private developments are also beginning to get underway. In 2006, a Dubai-based Afghan family opened a $25 million Coca Cola bottling plant in Afghanistan.[86]

While the country's current account deficit is largely financed with the donor money, only a small portion – about 15% – is provided directly to the government budget. The rest is provided to non-budgetary expenditure and donor-designated projects through the United Nations system and non-governmental organizations. The government had a central budget of only $350 million in 2003 and an estimated $550 million in 2004. The country's foreign exchange reserves totals about $500 million. Revenue is mostly generated through customs, as income and corporate tax bases are negligible.

Inflation had been a major problem until 2002. However, the depreciation of the Afghani in 2002 after the introduction of the new notes (which replaced 1,000 old Afghani by 1 new Afghani) coupled with the relative stability compared to previous periods has helped prices to stabilize and even decrease between December 2002 and February 2003, reflecting the turnaround appreciation of the new Afghani currency. Since then, the index has indicated stability, with a moderate increase toward late 2003.[79]

The Afghan government and international donors seem to remain committed to improving access to basic necessities, infrastructure development, education, housing and economic reform. The central government is also focusing on improved revenue collection and public sector expenditure discipline. The rebuilding of the financial sector seems to have been so far successful. Money can now be transferred in and out of the country via official banking channels. Since 2003, over sixteen new banks have opened in the country, including Afghanistan International Bank, Kabul Bank, Azizi Bank, Standard Chartered Bank, First Micro Finance Bank, and others. A new law on private investment provides three to seven-year tax holidays to eligible companies and a four-year exemption from exports tariffs and duties.

Some private investment projects, backed with national support, are also beginning to pick up steam in Afghanistan. An initial concept design called the City of Light Development, envisioned by Dr. Hisham N. Ashkouri, Principal of ARCADD, Inc. for the development and the implementation of a privately based investment enterprise has been proposed for multi-function commercial, historic and cultural development within the limits of the Old City of Kabul along the Southern side of the Kabul River and along Jade Meywand Avenue,[87] revitalizing some of the most commercial and historic districts in the City of Kabul, which contains numerous historic mosques and shrines as well as viable commercial activities among war damaged buildings. Also incorporated in the design is a new complex for the Afghan National Museum.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey and the Afghan Ministry of Mines and Industry, Afghanistan may be possessing up to 36 trillion cubic feet (1,000 km3) of natural gas, 3.6 billion barrels (570,000,000 m3) of petroleum and up to 1,325 million barrels (2.107E+8 m3) of natural gas liquids. This could mark the turning point in Afghanistan’s reconstruction efforts. Energy exports could generate the revenue that Afghan officials need to modernize the country’s infrastructure and expand economic opportunities for the beleaguered and fractious population.[27] Other reports show that the country has huge amounts of gold, copper, coal, iron ore and other minerals.[24][28][88] The government of Afghanistan is in the process of extracting and exporting its copper reserves, which will be earning $1.2 billion US dollars in royalties and taxes every year for the next 30 years. It will also provide permanent labor to 3,000 of its citizens.[89] Afghanistan has a particularly high level of corruption.

Infrastructure

Transport

Ariana Afghan Airlines is the national airlines carrier, with domestic flights between Kabul, Kandahar, Herat and Mazar-e Sharif. International flights include to Dubai, Frankfurt, Istanbul and a number of other destinations.[citation needed] There are also limited domestic and international flight services available from Kam Air, Pamir Airways and Safi Airlines.

The country has limited rail service with Turkmenistan. There are two railway projects currently in progress, one is between Herat and the Iranian city Mashad while another is between Kandahar and Quetta in Pakistan. Most people who travel from one city to another use bus services. Automobiles have recently become more widely available, with Toyota, Nissan and Hyundai dealerships in Kabul. A large number of second-hand vehicles are also arriving from the UAE. Nearly all highways and roads are being rebuilt in the country.

Communications and technology

Telecommunication services in the country are provided by Afghan Wireless, Etisalat, Roshan, Areeba and Afghan Telecom. In 2006, the Afghan Ministry of Communications signed a US$64.5 million agreement with ZTE Corporation for the establishment of a countrywide fibre optic cable network. This will improve telephone, internet, television and radio broadcast services throughout the country.[90] Around 500,000 (1.5% of the population) had internet access by the end of 2008.[91]

Television and radio broadcastings are available in most parts of the country, with local and international channels or stations.

The nation's post service is also operating. Package delivery services such as FedEx, DHL and others are also available.

Media

The media was tightly controlled under the Taliban and other periods in its history, and was relatively free in others. Under the Taliban, television was shut down in 1996, and print media were forbidden to publish commentary, photos or readers letters.[92] The only radio station broadcast religious programmes and propaganda, and aired no music.[92]

After the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001, press restrictions were gradually relaxed and private media diversified. Freedom of expression and the press is promoted in the 2004 constitution and censorship is banned, though defaming individuals or producing material contrary to the principles of Islam is prohibited. In 2008, Reporters Without Borders listed the media environment as 156 out of 173, with 1st being most free.[93] 400 publications are now registered and 60 radio stations, a major source of information, currently exist.[94] Foreign radio stations, such as the BBC World Service, also broadcast into the country. However, press freedom is threatened by the continuing war in Afghanistan, with kidnappings of journalists, harassment and death threats.

Education

As of 2006 more than four million male and female students were enrolled in schools throughout the country. However, there are still significant obstacles to education in Afghanistan, stemming from lack of funding, unsafe school buildings and cultural norms. A lack of women teachers is an issue that concerns some Afghan parents, especially in more conservative areas. Some parents will not allow their daughters to be taught by men.[95]

Literacy of the entire population is estimated (as of 1999) at 36%, the male literacy rate is 51% and female literacy is 21%. Up to now there are 9,500 schools in the country.

Another aspect of education that is rapidly changing in Afghanistan is the face of higher education. Following the fall of the Taliban, Kabul University was reopened to both male and female students. In 2006, the American University of Afghanistan also opened its doors, with the aim of providing a world-class, English-language, co-educational learning environment in Afghanistan. The university accepts students from Afghanistan and the neighboring countries. Construction work will soon start at the new site selected for University of Balkh in Mazari Sharif. The new building for the university, including the building for the Engineering Department, would be constructed at 600 acres (2.4 km²) of land at the cost of 250 million US dollars.[96]

A new military school is in function to properly train and educate Afghan soldiers.

Images of Afghanistan

| This section looks like an image gallery. Wikipedia is not a collection of images and policy discourages galleries. Please help by moving freely licensed images to Wikimedia Commons, possibly creating a gallery of the same name if one does not already exist. See Wikipedia's guide to writing better articles for further suggestions. |

|

Kotal-e Salang mountain pass in northern Afghanistan. |

The Afghanistan-Tajikistan Friendship Border-crossing bridge, the largest in Central Asia.[97] |

||

|

A mosque in Khost, one of the provinces of Afghanistan. |

Notes

| a.^ | Other terms that can be used as demonyms are Afghani[98] and Afghanistani.[99] |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g "Afghanistan". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. December 13, 2007. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/af.html#People.

- ^ "Afghanistan", CIA - The World Factbook 2007

- ^ a b c d "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2008/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?sy=2004&ey=2008&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=512&s=NGDPD%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CLP&grp=0&a=&pr.x=62&pr.y=10.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004.

- ^ The 2007 Middle East & Central Asia Politics, Economics,and Society Conference University of Utah

- ^ "Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East & Central Asia" May 2006, International Monetary Fund

- ^ CIA world factbook, Afghanistan - Geography (Location: Southern Asia)

- ^ University of California, [1], University of Pennsylvania, World Bank; U.S. maps; [2] ; University of Washington Syracuse University

- ^ http://www.umich.edu/~iinet/cmenas/info.htm

- ^ a b Ahmad Shah Durrani, Britannica Concise.

- ^ The Decline of the Pashtuns in Afghanistan, Anwar-ul-Haq Ahady, Asian Survey, Vol. 35, No. 7. (Jul., 1995), pp. 621–634.

- ^ Morgenstierne, G. (1999). "AFGHĀN". Encyclopaedia of Islam (CD-ROM Edition v. 1.0 ed.). Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- ^ Nancy Hatch Dupree - The Story of Kabul (Mongols)

- ^ "Afghan" (with ref. to "Afghanistan: iv. Ethnography") by Ch. M. Kieffer, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online Edition 2006.

- ^ extract from "Passion of the Afghan" by Khushal Khan Khattak; translated by C. Biddulph in "Afghan Poetry Of The 17th Century: Selections from the Poems of Khushal Khan Khattak", London, 1890

- ^ "Transactions of the year 908" by Zāhir ud-Dīn Mohammad Bābur in Bāburnāma, translated by John Leyden, Oxford University Press: 1921.

- ^ Elphinstone, M., "Account of the Kingdom of Cabul and its Dependencies in Persia and India", London 1815; published by Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown

- ^ E. Bowen, "A New & Accurate Map of Persia" in A Complete System Of Geography, Printed for W. Innys, R. Ware [etc.], London 1747

- ^ E. Huntington, "The Anglo-Russian Agreement as to Tibet, Afghanistan, and Persia", Bulletin of the American Geographical Society, Vol. 39, No. 11 (1907)

- ^ a b MECW Volume 18, p. 40; The New American Cyclopaedia - Vol. I, 1858

- ^ M. Ali, "Afghanistan: The War of Independence, 1919", Kabul [s.n.], 1960

- ^ Afghanistan's Constitution of 1923 under King Amanullah Khan (English translation).

- ^ "History of Environmental Change in the Sistan Basin 1976–2005" (pdf). http://postconflict.unep.ch/publications/sistan.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ^ a b Gold and copper discovered in Afghanistan

- ^ Uranium Mining Issues: 2005 Review

- ^ 16 detained for smuggling chromites, Pajhwok Afghan News.

- ^ a b Afghanistan’s Energy Future and its Potential Implications, Eurasianet.org.

- ^ a b Govt plans to lease out Ainak copper mine, Pajhwok Afghan News.

- ^ Sites in Perspective, chapter 3 of Nancy Hatch Dupree, An Historical Guide To Afghanistan.

- ^ Afghanistan, Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006 (specifically John Ford Shroder, B.S., M.S., Ph.D. Regents Professor of Geography and Geology, University of Nebraska. Editor, Himalaya to the Sea: Geology, Geomorphology, and the Quaternary and other books).

- ^ It is unlikely because of the migration significantly north of the Caspian. Bryant, Edwin F. (2001) The quest for the origins of Vedic culture: the Indo-Aryan migration debate Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, ISBN 0-19-513777-9

- ^ Lal, B. B. and Saraswat, K. S. (2005) The homeland of the Aryans : evidence of Ṛigvedic flora and fauna & archaeology Aryan Books International, New Delhi, ISBN 81-7305-283-2

- ^ Sethna, Kaikhushru Dhunjibhoy (1992) The Problem of Aryan Origins Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi, ISBN 81-85179-67-0

- ^ The history of Afghanistan, Ghandara.com website

- ^ Afghanistan: Achaemenid dynasty rule, Ancient Classical History, about.com

- ^ Dani, A. H. and B. A. Litvinsky. “The Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom”. In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 103–118. ISBN 92-3-103211-9

- ^ Zeimal, E. V. “The Kidarite Kingdom in Central Asia”. In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996, Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 119–133. ISBN 92-3-103211-9

- ^ Litvinsky, B. A. “The Hephthalite Empire”. In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996, Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 135–162. ISBN 92-3-103211-9

- ^ Ali Akbar Dehkhoda, Dehkhoda Dictionary, p. 8457

- ^ Ghubar, Mir Ghulam Mohammad, Khorasan, 1937 Kabul Printing House, Kabul)

- ^ Tajikistan Development Gateway, from History of Afghanistan by the Development Gateway Foundation

- ^ Ghaznavid Dynasty, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Edition.

- ^ Timurid Dynasty, Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Edition.

- ^ “Ašraf Ghilzai” by Prof. D. Balland, Encyclopaedia Iranica Online Edition 2006.

- ^ “The Hotakis” in "Afghanistan", Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ a b The Durranti dynasty, in “Afghanistan”, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ Ahmad Shah Durrani, Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ^ The South, chapter 16 of Nancy Hatch Dupree, An Historical Guide To Afghanistan.

- ^ "Education in Afghanistan," published in Encylopaedia Iranica, volume VIII - pp. 237-241...Link

- ^ Hanifi, M. Jamil. "GHILZĪ or GHALZĪ". Encyclopædia Iranica (Online Edition ed.). United States: Columbia University. http://www.iranica.com/newsite/articles/v10f6/v10f637.html.

- ^ Prashad, Vijay (2001-09-15). "War Against the Planet". ZMag. http://www.zmag.org/prashcalam.htm. Retrieved on 2008-03-21.

- ^ "The CIA's Intervention in Afghanistan (Interview with Zbigniew Brzezinski)". Le Nouvel Observateur. 1998-01-21. http://www.globalresearch.ca/articles/BRZ110A.html. Retrieved on 2008-03-15.

- ^ Afghanistan: History, Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ^ http://physiciansforhumanrights.org/library/documents/reports/talibans-war-on-women.pdf

- ^ Erik Eckholm (2001-12-26). "A NATION CHALLENGED: PENALTIES; Taliban Justice: Stadium Was Scene of Gory Punishment". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C00E6DD1231F935A15751C1A9679C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved on 2008-05-19.

- ^ Afghanistan, Opium and the Taliban [3]

- ^ Bush At War, Bob Woodward, 2002

- ^ [4] - New Supreme Court Could Mark Genuine Departure - August 13, 2006

- ^ Text used in this cited section originally came from: Afghanistan (Feb 2005) profile from the Library of Congress Country Studies project.

- ^ "CIA World Factbook". https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/print/af.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-05.

- ^ BBC News - Afghan poll's ethnic battleground - October 6, 2004

- ^ L. Dupree, "Afghānistān: (iv.) ethnocgraphy", in Encyclopædia Iranica, Online Edition 2006, (LINK)

- ^ a b "A survey of the Afghan people - Afghanistan in 2006", The Asia Foundation, technical assistance by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS; India) and Afghan Center for Socio-economic and Opinion Research (ACSOR), Kabul, 2006, PDF

- ^ a b ABC NEWS/BBC/ARD POLL – AFGHANISTAN: WHERE THINGS STAND, February 9th, 2009, p. 38-40

- ^ "Afghānistān: (v.) languages" by L. Dupree, Encyclopædia Iranica Online Edition 2006.

- ^ a b Heathcote, Tony (1980, 2003) "The Afghan Wars 1839–1919", Sellmount Staplehurst

- ^ G.V. Brandolini. Afghanistan cultural heritage. Orizzonte terra, Bergamo. 2007. 64 p.

- ^ "Modern literature of Afghanistan" by R. Farhādī, Encyclopaedia Iranica, xii, Online Edition.

- ^ Afghanmagazine.com - Ustad Khalilullah Khalili - 1997

- ^ Afghanmagazine.com - Kharaabat - by Yousef Kohzad - 2000

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica - Afghanistan...Link (PDF)

- ^ Goring, R. (ed): "Larousse Dictionary of Beliefs & Religions" (Larousse: 1994), pg. 581–58, Table: "Population Distribution of Major Beliefs", ISBN 0-7523-0000-8, Note: "... Figures have been compiled from the most accurate recent available information and are in most cases correct to the nearest 1% ..."

- ^ Hinduism Today: Hindus Abandon Afghanistan

- ^ BBC South Asia: Sikhs struggle in Afghanistan

- ^ Washingtonpost.com - Afghan Jew Becomes Country's One and Only - N.C. Aizenman

- ^ Morales, Victor (2005-03-28). "Poor Afghanistan". Voice of America. http://www.voanews.com/english/archive/2005-03/2005-03-28-voa53.cfm. Retrieved on 2006-09-10.

- ^ North, Andrew (2004-03-30). "Why Afghanistan wants $27.6bn". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3582023.stm. Retrieved on 2006-09-10.

- ^ CIA - The World Factbook - Afghanistan

- ^ a b c Fujimura, Manabu (2004) "Afghan Economy After the Election", Asian Development Bank Institute

- ^ Pajhwok Afghan News, Afghanistan receives $3.3b remittances from expats, Oct. 19, 2007.

- ^ Macroeconomics & Economic Growth in South Asia, The World Bank.

- ^ Afghan opium production at record high

- ^ UN horrified by surge in opium trade in Helmand

- ^ Poppies for Peace: Reforming Afghanistan’s Opium Industry

- ^ "Midday Business Report: Black & Veatch unit gains piece of Afghan contract", The Kansas City Star.

- ^ "Coca-Cola opens plant in Afghanistan", Contra Costa Times.

- ^ Kabul - City of Light Project

- ^ Pajhwok Afghan News, Afghanistan has huge mineral resources: survey, Nov. 14, 2007.

- ^ Pajhwok Afghan News, Chinese company wins bidding for Ainak copper extraction, Nov. 20, 2007.

- ^ Ministry signs contract with Chinese company, Pajhwok Afghan News.

- ^ ITU statistics

- ^ a b Dartnell, M. Y. Insurgency Online: Web Activism and Global Conflict. University of Toronto Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0802085535.

- ^ Press Freedom 2008 Index, Reporters Without Borders.

- ^ Afghanistan Press Report 2008, Freedom House.

- ^ Mojumdar, Aunohita: "Afghan Schools' Money Problems", BBC News, 2007. [5]

- ^ Pakistan grants $10m for Balkh University, Pajhwok Afghan News.

- ^ http://kabul.usembassy.gov/pr082607.html

- ^ Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. LINK (accessed: November 13, 2007)

- ^ Dictionary.com. WordNet 3.0. Princeton University. LINK (accessed: November 13, 2007)

Bibliography

|

|

|

External links

![]() Textbooks from Wikibooks

Textbooks from Wikibooks

![]() Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote

![]() Source texts from Wikisource

Source texts from Wikisource

![]() Images and media from Commons

Images and media from Commons

![]() News stories from Wikinews

News stories from Wikinews

- General information

- Afghanistan entry at The World Factbook

- Afghanistan from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Afghanistan at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of Afghanistan

- Afghanistan travel guide from Wikitravel

- Government

- Islamic Republic of Afghanistan: Office of the President

- Afghanistan National Development Strategy (ANDS)

- Afghanistan Investment Support Agency (AISA)

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

- The Present Afghan Conflict

- "Struggle for Kabul: The Taliban Advance." Icos report, December 2008

- "Breaking point: measuring progress in Afghanistan." Seema Patel and Steven Ross. Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), February, 2007.

- Ali, Tariq. "Afghanistan: Mirage of the good war" New Left Review (50), March-April 2008.

- Canadian Peace Alliance. Bring the troops home now: Why a military mission will not bring peace to Afghanistan. (February 2007)

- Families for Peaceful Tomorrows. Afghanistan: Ending a Failed Military Strategy.

- Friedman, George. "Strategic Divergence: The War Against the Taliban and the War Against Al Qaeda." Stratfor Global Intelligence. January 2009.

- Media

- Digital Library

- Other

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||