Soviet war in Afghanistan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Soviet war in Afghanistan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War, Civil war in Afghanistan | |||||||

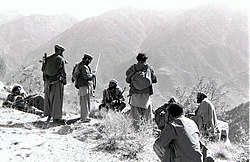

Soviet soldier in Afghanistan, 1988. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Soviet forces: 115,000 Afghan forces: 90,000-100,000 (in 1984)[5] |

150,000-350,000 (in 1984)[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Soviet: 14,453 killed (Soviet figures), 15,051 killed (independent figures) |

unknown | ||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

The Soviet war in Afghanistan (also known as the Soviet-Afghan War or the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan) was a nine-year conflict involving Soviet Union forces supporting the Marxist People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) government against the mujahideen resistance. The latter group found support from a variety of sources including the United States, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and other Muslim nations in the context of the Cold War. This conflict was concurrent to the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War.

The initial Soviet deployment of the 40th Army in Afghanistan began on December 24, 1979.[6] The final troop withdrawal began on May 15, 1988, and ended on February 15, 1989. Due to the interminable nature of the war, the conflict in Afghanistan has often been referred to as the Soviet equivalent of the United States' Vietnam War.

[edit] Background

[edit] Afghanistan demographics

Having seen many cultures come and go throughout the centuries, the region today known as Afghanistan has been predominantly Muslim since 1882. The country's nearly impassable mountains and desert terrain have contributed to its ethnically and linguistically diverse population. Pashtuns are the largest political and cultural ethnic group in the country; however the national population also consists of Tajiks, Hazara, Aimak, Uzbeks, Uyghur, Turkmen and other small groups.

Many Soviet Muslims in Central Asia had tribal kinship relationships in both Iran and Afghanistan.

Russian military involvement in Afghanistan has a long history, going back to Tsarist expansions in the so-called "Great Game" between Russia and Britain. This began in the 19th century with such events as the Panjdeh Incident, a military skirmish that occurred in 1885 when Russian forces seized Afghan territory south of the Oxus River around an oasis at Panjdeh. This interest in the region continued on through the Soviet era, with billions in economic and military aid sent to Afghanistan between 1955 and 1978.[7]

In February 1979, the Islamic Revolution ousted the US-backed Shah from Afghanistan's neighbor Iran and the United States ambassador to Afghanistan was kidnapped and killed by Islamists, despite attempts by the Afghan security forces and Soviet advisers to free him.

The United States then deployed twenty ships to the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea including two aircraft carriers, and there was a constant stream of threats of warfare between the US and Iran.[8]

March 1979 marked the signing of the US-backed peace agreement between Israel and Egypt. The Soviet leadership saw the agreement as a major advantage for the United States. One Soviet newspaper stated that Egypt and Israel were now “gendarmes of the Pentagon”. The Soviets viewed the treaty not only as a peace agreement between their erstwhile allies in Egypt and the US-supported Israelis but also as a military pact.[9] In addition, the US sold more than 5,000 missiles to Saudi Arabia and also supplied the Royalists in the North Yemen Civil War against the communist rebellion. Also, the Soviet Union's previously strong relations with Iraq had recently soured. In June 1978, Iraq began entering into friendlier relations with the Western world and buying French- and Italian-made weapons, though the vast majority still came from the Soviet Union and their Warsaw Pact allies, and China.

[edit] Democratic Republic of Afghanistan

[edit] The Saur Revolution

King Mohammed Zahir Shah, who died in 2007, acceded to the throne and reigned from 1933 to 1973. Zahir's cousin, Mohammad Daoud Khan, served as Prime Minister from 1954 to 1963. The Marxist PDPA party's strength grew considerably in these years. In 1967, the PDPA split into two rival factions, the Khalq (Masses) faction headed by Nur Muhammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin and the Parcham (Flag) faction led by Babrak Karmal.

Former Prime Minister Daoud seized power in an almost bloodless military coup on July 17, 1973, after charges of corruption and poor economic conditions against the King's government. Daoud put an end to the monarchy but his attempts at economic and social reforms were unsuccessful. Intense opposition from factions of the PDPA was sparked by the repression imposed on them by Daoud's regime and the death of a leading PDPA member, Mir Akbar Khyber.[10] The mysterious circumstances of Khyber's death sparked massive anti-Daoud demonstrations in Kabul, which resulted in the arrest of several prominent PDPA leaders.[11]

On April 27, 1978, the Afghan army, which had been sympathetic to the PDPA cause, overthrew and executed Daoud along with members of his family.[12] Nur Muhammad Taraki, Secretary General of the PDPA, became President of the Revolutionary Council and Prime Minister of the newly established Democratic Republic of Afghanistan.

[edit] Factions inside the PDPA

After the revolution, Taraki assumed the Presidency, Prime Ministership and General Secretary of the PDPA. The government was divided along factional lines, with President Taraki and Deputy Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin of the Khalq faction against Parcham leaders such as Babrak Karmal and Mohammad Najibullah. Within the PDPA, conflicts resulted in exiles, purges and executions of Parcham members.[13]

During its first 18 months of rule, the PDPA applied a Soviet (council)-style program of reforms. Decrees setting forth changes in marriage customs and land reform were not received well by a population deeply immersed in tradition and Islam, particularly by the powerful landlords who were hit hard by the abolition of usury and the cancellation of farmers' debts. By mid-1978, a rebellion started with rebels attacking the local military garrison in the Nuristan region of eastern Afghanistan and soon civil war spread throughout the country. In September 1979, Deputy Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin seized power after a palace shootout that resulted in the death of President Taraki. Over two months of instability overwhelmed Amin's regime as he moved against his opponents in the PDPA and the growing rebellion.

[edit] Soviet-Afghan relations

After the Russian Revolution, as early as 1919, the Soviet government gave Afghanistan aid in the form of a million gold rubles, small arms, ammunition, and a few aircraft to support the resistance during the Third Anglo-Afghan War. In 1924, the USSR again gave military aid to Afghanistan. It received small arms, aircraft and military training in the Soviet Union for Afghan army officers. Soviet-Afghan military cooperation began on a regular basis in 1956, when both countries signed another agreement. After this, all Afghan military officers were trained in the USSR.

[edit] Initiation of the insurgency

In June 1975, militants from the Jamiat Islami party attempted to overthrow the government. They started their rebellion in the Panjshir valley, some 100 kilometers north of Kabul, and in a number of other provinces of the country. However, government forces easily defeated the insurgency and a sizable portion of the insurgents sought refuge in Pakistan where they enjoyed the support of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's government, which had been alarmed by Daoud's revival of the Pashtunistan issue.[14]

In 1978 the Taraki government initiated a series of reforms, including modernization of the civil and especially marriage law, aimed at "uprooting feudalism" in Afghan society.[15] The government brooked no opposition to the reforms[13] and responded with violence to unrest. Between April 1978 and the Soviet invasion of December 1979, an estimated 27,000 political prisoners were executed at the notorious[16] Pul-e-Charkhi prison, including many village mullahs and headmen.[17] Other members of the traditional elite, the religious establishment and intelligentsia fled the country.[17]

Consequently, the reaction against the reforms was also violent, and large parts of the country went into open rebellion. The Parcham Government claimed that 11,000 were executed during the Amin/Taraki period in response to the revolts. [6] The revolt began in October among the Nuristani tribes of the Kunar Valley, and rapidly spread among the other ethnic groups, including the Pashtun majority. The Afghan army fought back violently, but couldn't subdue the large insurgency. By the spring of 1979, 24 of the 28 provinces had suffered outbreaks of violence.[18] The rebellion began to take hold in the cities: in March 1979 in Herat, rebels led by Ismail Khan killed approximately 10 soldiers. The Afghan Air Force retaliated with a bombing campaign that killed 24,000 inhabitants of the city.[19] Despite these drastic measures, by the end of 1980, out of the 80,000 soldiers strong Afghan Army, more than half had either deserted or joined the rebels.[18]

[edit] 1979: Soviet deployment

The Afghan government repeatedly requested the introduction of Soviet forces in Afghanistan in the spring and summer of 1979. They requested Soviet troops to provide security and to assist in the fight against the mujahideen rebels. On April 14, 1979, the Afghan government requested that the USSR send 15 to 20 helicopters with their crews to Afghanistan, and on June 16, the Soviet government responded and sent a detachment of tanks, BMPs, and crews to guard the government in Kabul and to secure the Bagram and Shindand airfields. In response to this request, an airborne battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel A. Lomakin, arrived at the Bagram Air Base on July 7. They arrived without their combat gear, disguised as technical specialists. They were the personal bodyguards for President Taraki. The paratroopers were directly subordinate to the senior Soviet military adviser and did not interfere in Afghan politics.

After a month, the Afghan requests were no longer for individual crews and subunits, but for regiments and larger units. In July, the Afghan government requested that two motorized rifle divisions be sent to Afghanistan. The following day, they requested an airborne division in addition to the earlier requests. They repeated these requests and variants to these requests over the following months right up to December 1979. However, the Soviet government was in no hurry to grant them.

The anti-communist rebels garnered support from the United States. As stated by the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency and current US Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, in his memoirs From the Shadows, the US intelligence services began to aid the rebel factions in Afghanistan six months before the Soviet deployment. On July 3, 1979, US President Jimmy Carter signed an executive order authorizing the CIA to conduct covert propaganda operations against the communist regime.

Carter advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski stated: "According to the official version of history, CIA aid to the mujahideen began during 1980, that is to say, after the Soviet army invaded Afghanistan, December 24, 1979. But the reality, secretly guarded until now, is completely otherwise." Brzezinski himself played a fundamental role in crafting US policy, which, unbeknownst even to the mujahideen, was part of a larger strategy "to induce a Soviet military intervention." In a 1998 interview with Le Nouvel Observateur, Brzezinski recalled: "We didn't push the Russians to intervene, but we knowingly increased the probability that they would...That secret operation was an excellent idea. It had the effect of drawing the Soviets into the Afghan trap...The day that the Soviets officially crossed the border, I wrote to President Carter. We now have the opportunity of giving to the Soviet Union its Vietnam War."[20]

Additionally, on July 3, 1979, Carter signed a presidential finding authorizing funding for anticommunist guerrillas in Afghanistan.[21] As a part of the Central Intelligence Agency program Operation Cyclone, the massive arming of Afghanistan's mujahideen was started.[22]

The Soviet Union decided to intervene militarily in Afghanistan in order to preserve the communist regime. Based on information from the KGB, Soviet leaders felt that Amin destabilized the situation in Afghanistan. Following Amin's initial coup against and killing of President Taraki, the KGB station in Kabul warned that his leadership would lead to "harsh repressions, and as a result, the activation and consolidation of the opposition."[23]

The Soviets established a special commission on Afghanistan, of KGB chairman Yuri Andropov, Ponomaryev from the Central Committee and Dimitry Ustinov, the Minister of Defense. In late April 1978, they reported that Amin was purging his opponents, including Soviet loyalists; his loyalty to Moscow was in question; and that he was seeking diplomatic links with Pakistan and possibly the People's Republic of China. Of specific concern were Amin's secret meetings with the US chargé d'affaires J. Bruce Amstutz, which, while never amounting to any agreement between Amin and the United States, sowed suspicion in the Kremlin.[24]

Information obtained by the KGB from its agents in Kabul provided the last arguments to eliminate Amin; supposedly, two of Amin's guards killed the former president Nur Muhammad Taraki with a pillow, and Amin was suspected to be a CIA agent. The latter, however, is still disputed: Amin repeatedly demonstrated official friendliness to the Soviet Union. Soviet General Vasily Zaplatin, a political advisor at that time, claimed that four of President Taraki's ministers were responsible for the destabilization. However, Zaplatin failed to emphasize this enough.[25]

[edit] 1979: Soviet invasion

On December 7, 1979, the Soviet advisors to the Afghan Armed Forces advised them to undergo maintenance cycles for their tanks and other crucial equipment. Meanwhile, telecommunications links to areas outside of Kabul were severed, isolating the capital. With a deteriorating security situation, large numbers of Soviet airborne forces joined stationed ground troops and began to land in Kabul on December 25. Simultaneously, Amin moved the offices of the president to the Tajbeg Palace, believing this location to be more secure from possible threats. According to Colonel General Tukharinov and Merimsky, Amin was fully informed of the military movements, having requested Soviet military assistance to northern Afghanistan on December 17.[26][27] His brother and General Dmitry Chiangov met with the commander of the 40th Army before Soviet troops entered the country, to work out initial routes and locations for Soviet troops.[28]

On December 27, 1979, 700 Soviet troops dressed in Afghan uniforms, including KGB OSNAZ and GRU SPETSNAZ special forces from the Alpha Group and Zenith Group, occupied major governmental, military and media buildings in Kabul, including their primary target - the Tajbeg Presidential Palace.

That operation began at 19:00 hr., when the Soviet Zenith Group destroyed Kabul's communications hub, paralyzing Afghan military command. At 19:15, the assault on Tajbeg Palace began; as planned, president Hafizullah Amin was killed. Simultaneously, other objectives were occupied (e.g. the Ministry of Interior at 19:15). The operation was fully complete by the morning of December 28, 1979.

The Soviet military command at Termez, Uzbek SSR, announced on Radio Kabul that Afghanistan had been "liberated" from Amin's rule. According to the Soviet Politburo they were complying with the 1978 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Good Neighborliness and Amin had been "executed by a tribunal for his crimes" by the Afghan Revolutionary Central Committee. That committee then elected as head of government former Deputy Prime Minister Babrak Karmal, who had been demoted to the relatively insignificant post of ambassador to Czechoslovakia following the Khalq takeover, and that it had requested Soviet military assistance. [29]

Soviet ground forces, under the command of Marshal Sergei Sokolov, entered Afghanistan from the north on December 27. In the morning, the 103rd Guards 'Vitebsk' Airborne Division landed at the airport at Bagram and the deployment of Soviet troops in Afghanistan was underway. The force that entered Afghanistan, in addition to the 103rd Guards Airborne Division, was under command of the 40th Army and consisted of the 108th and 5th Guards Motor Rifle Divisions, the 860th Separate Motor Rifle Regiment, the 56th Separate Airborne Assault Brigade, the 36th Mixed Air Corps. Later on the 201st and 58th Motor Rifle Divisions also entered the country, along with other smaller units.[30] In all, the initial Soviet force was around 1,800 tanks, 80,000 soldiers and 2,000 AFVs. In the second week alone, Soviet aircraft had made a total of 4,000 flights into Kabul.[31] With the arrival of the two later divisions, the total Soviet force rose to over 100,000 personnel.

[edit] December 1979-February 1980: Occupation

The first phase began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and their first battles with various opposition groups.

Soviet troops entered Afghanistan along two ground routes and one air corridor, quickly taking control of the major urban centers, military bases and strategic installations. However, the presence of Soviet troops did not have the desired effect of pacifying the country. On the contrary, it exacerbated a nationalistic feeling, causing the rebellion to spread even more.[32] Babrak Karmal, Afghanistan's new president, charged the Soviets with causing an increase in the unrest, and demanded that the 40th Army step in and quell the rebellion, as his own army had proved untrustworthy.[33] Thus, Soviet troops found themselves drawn into fighting against urban uprisings, tribal armies (called lashkar), and sometimes against mutinying Afghan Army units. These forces mostly fought in the open, and Soviet airpower and artillery made short work of them.[34]

[edit] March 1980-April 1985: Soviet offensives

The war now developed into a new pattern: the Soviets occupied the cities and main axis of communication, while the mujahideen, divided into small groups, waged a guerrilla war. Almost 80 percent of the country escaped government control. Soviet troops were deployed in strategic areas in the northeast, especially along the road from Termez to Kabul. In the west, a strong Soviet presence was maintained to counter Iranian influence. Conversely, some regions such as Nuristan and Hazarajat were virtually untouched by the fighting, and lived in almost complete independence.

Periodically the Soviet Army undertook multi-divisional offensives into mujahideen-controlled areas. Between 1980 and 1985, nine offensives were launched into the strategic Panjshir Valley, but government control of the area did not improve.[35] Heavy fighting also occurred in the provinces neighbouring Pakistan, where cities and government outposts were constantly under siege by the mujahideen. Massive Soviet operations would regularly break these sieges, but the mujahideen would return as soon as the coast was clear.[36] In the west and south, fighting was more sporadic, except in the cities of Herat and Kandahar, that were always partly controlled by the resistance.[37]

On his arrival in power in March 1985, the new Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev expressed his impatience with the Afghan conflict. He demanded that a solution be found before a one-year deadline. As a result, the size of the LCOSF (Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces) was increased to 108,800 and fighting increased throughout the country, making 1985 the bloodiest year of the war. However, despite suffering heavily, the mujahideen were able to remain in the field and continue resisting the Soviets.

[edit] 1980s: Insurrection

By the mid-1980s, the Afghan resistance movement, assisted by the United States, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, PRC and others, contributed to Moscow's high military costs and strained international relations. The US viewed the conflict in Afghanistan as an integral Cold War struggle, and the CIA provided assistance to anti-Soviet forces through the Pakistani intelligence services, in a program called Operation Cyclone.[38][39]

A similar movement occurred in other Muslim countries, bringing contingents of so-called Afghan Arabs, foreign fighters who wished to wage jihad against the atheist communists. Notable among them was a young Saudi named Osama bin Laden, whose Arab group eventually evolved into al-Qaeda.[40][41]

In the course of the guerrilla war, leadership came to be distinctively associated with the title of "commander". It applied to independent leaders, eschewing identification with elaborate military bureaucracy associated with such ranks as general. As the war produced leaders of reputation, "commander" was conferred on leaders of fighting units of all sizes, signifying pride in independence, self-sufficiency, and distinct ties to local communities. The title epitomized Afghan pride in their struggle against a powerful foe. Segmentation of power and religious leadership were the two values evoked by nomenclature generated in the war. Neither had been favored in the ideology of the former Afghan state.

Afghanistan's resistance movement was born in chaos, spread and triumphed chaotically, and did not find a way to govern differently. Virtually all of its war was waged locally by regional warlords. As warfare became more sophisticated, outside support and regional coordination grew. Even so, the basic units of mujahideen organization and action continued to reflect the highly segmented nature of Afghan society.[42]

Olivier Roy estimates that after four years of war, there were at least 4,000 bases from which mujahideen units operated. Most of these were affiliated with the seven expatriate parties headquartered in Pakistan, which served as sources of supply and varying degrees of supervision. Significant commanders typically led 300 or more men, controlled several bases and dominated a district or a sub-division of a province. Hierarchies of organization above the bases were attempted. Their operations varied greatly in scope, the most ambitious being achieved by Ahmad Shah Massoud of the Panjshir valley north of Kabul. He led at least 10,000 trained troops at the end of the Soviet war and had expanded his political control of Tajik-dominated areas to Afghanistan's northeastern provinces under the Supervisory Council of the North.[42]

Roy also describes regional, ethnic and sectarian variations in mujahideen organization. In the Pashtun areas of the east, south and southwest, tribal structure, with its many rival sub-divisions, provided the basis for military organization and leadership. Mobilization could be readily linked to traditional fighting allegiances of the tribal lashkar (fighting force). In favorable circumstances such formations could quickly reach more than 10,000, as happened when large Soviet assaults were launched in the eastern provinces, or when the mujahideen besieged towns, such as Khost in Paktia province in July 1983[43]. But in campaigns of the latter type the traditional explosions of manpower--customarily common immediately after the completion of harvest--proved obsolete when confronted by well dug-in defenders with modern weapons. Lashkar durability was notoriously short; few sieges succeeded.[42]

Mujahideen mobilization in non-Pashtun regions faced very different obstacles. Prior to the invasion, few non-Pashtuns possessed firearms. Early in the war they were most readily available from army troops or gendarmerie who defected or were ambushed. The international arms market and foreign military support tended to reach the minority areas last. In the northern regions, little military tradition had survived upon which to build an armed resistance. Mobilization mostly came from political leadership closely tied to Islam. Roy convincingly contrasts the social leadership of religious figures in the Persian- and Turkish-speaking regions of Afghanistan with that of the Pashtuns. Lacking a strong political representation in a state dominated by Pashtuns, minority communities commonly looked to pious learned or charismatically revered pirs (saints) for leadership. Extensive Sufi and maraboutic networks were spread through the minority communities, readily available as foundations for leadership, organization, communication and indoctrination. These networks also provided for political mobilization, which led to some of the most effective of the resistance operations during the war.[42]

The mujahideen favoured sabotage operations. The more common types of sabotage included damaging power lines, knocking out pipelines and radio stations, blowing up government office buildings, air terminals, hotels, cinemas, and so on. From 1985 through 1987, an average of over 600 "terrorist acts" a year were recorded. In the border region with Pakistan, the mujahideen would often launch 800 rockets per day. Between April 1985 and January 1987, they carried out over 23,500 shelling attacks on government targets. The mujahideen surveyed firing positions that they normally located near villages within the range of Soviet artillery posts, putting the villagers in danger of death from Soviet retaliation. The mujahideen used land mines heavily. Often, they would enlist the services of the local inhabitants, even children.

They concentrated on both civilian and military targets, knocking out bridges, closing major roads, attacking convoys, disrupting the electric power system and industrial production, and attacking police stations and Soviet military installations and air bases. They assassinated government officials and PDPA members, and laid siege to small rural outposts. In March 1982, a bomb exploded at the Ministry of Education, damaging several buildings. In the same month, a widespread power failure darkened Kabul when a pylon on the transmission line from the Naghlu power station was blown up. In June 1982 a column of about 1,000 young communist party members sent out to work in the Panjshir valley were ambushed within 30 km of Kabul, with heavy loss of life. On September 4, 1985, insurgents shot down a domestic Bakhtar Airlines plane as it took off from Kandahar airport, killing all 52 people aboard.

Mujahideen groups used for assassination had three to five men in each. After they received their mission to kill certain government officials, they busied themselves with studying his pattern of life and its details and then selecting the method of fulfilling their established mission. They practiced shooting at automobiles, shooting out of automobiles, laying mines in government accommodation or houses, using poison, and rigging explosive charges in transport.

In May 1985, the seven principal rebel organizations formed the Seven Party Mujahideen Alliance to coordinate their military operations against the Soviet army. Late in 1985, the groups were active in and around Kabul, unleashing rocket attacks and conducting operations against the communist government.

By mid-1987 the Soviet Union announced it would start withdrawing its forces. Sibghatullah Mojaddedi was selected as the head of the Interim Islamic State of Afghanistan, in an attempt to reassert its legitimacy against the Moscow-sponsored Kabul regime. Mojaddedi, as head of the Interim Afghan Government, met with then Vice President of the United States George H. W. Bush, achieving a critical diplomatic victory for the Afghan resistance. Defeat of the Kabul government was their solution for peace. This confidence, sharpened by their distrust of the United Nations, virtually guaranteed their refusal to accept a political compromise.

[edit] Foreign involvement and aid to the mujahideen

The Afghan army was supported by a number of other countries -- the US and Saudi Arabia offering the greatest financial support. However, the Afghans were also aided by others: the UK, Egypt, China, Iran, and Pakistan. Ground support, for political reasons, was limited to regional countries.

United States President Jimmy Carter insisted that what he termed "Soviet aggression" could not be viewed as an isolated event of limited geographical importance but had to be contested as a potential threat to US influence in the Persian Gulf region. The US was also worried about the USSR gaining access to the Indian Ocean by coming to an arrangement with Pakistan.

After the Soviet deployment, Pakistan's military ruler General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq started accepting financial aid from the Western powers to aid the mujahideen.[44] In 1981, following the election of US President Ronald Reagan, aid for the mujahideen through Zia's Pakistan significantly increased, mostly due to the efforts of Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson and CIA officer Gust Avrakotos.

Paramilitary Officers were instrumental in training, equipping and sometimes leading Mujihadeen forces against the Red Army. Although the CIA in general and Charlie Wilson, a Texas Congressman, have received most of the attention, the key architect of this strategy was Michael G. Vickers, a young Paramilitary Officer from the CIA's famed Special Activities Division. [45]

The United States, the United Kingdom, and Saudi Arabia became major financial contributors, the United States donating "$600 million in aid per year, with a matching amount coming from the Persian Gulf states."[46] The People's Republic of China also sold Type 59 tanks, Type 68 assault rifles, Type 56 assault rifles, Type 69 RPGs, and much more to mujahideen in co-operation with the CIA, as did Egypt with assault rifles. Of particular significance was the donation of US-made FIM-92 Stinger anti-aircraft missile systems, which increased aircraft losses of the Soviet Air Force.[47]

In March 1985, the US government adopted National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) 166, which set a goal of military victory for the mujahideen. After 1985 the CIA and Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) placed greater pressure on the mujahideen to attack government strongholds. Under direct instructions from Director of Central Intelligence William Casey, the CIA initiated programs for training Afghans in techniques such as car bombs and assassinations and in engaging in cross-border raids into the USSR.[48]

Pakistan's ISI and Special Service Group (SSG) were actively involved in the conflict, and in cooperation with the CIA and the United States Army Special Forces, as well as the British Special Air Service, supported the mujahideen.

The theft of large sums of aid spurred Pakistan's economic growth, but along with the war in general had devastating side effects for that country. The siphoning off of aid weapons in the port city of Karachi contributed to disorder and violence there, while heroin entering from Afghanistan to pay for arms contributed to addiction problems.[49]

In retaliation for Pakistan's assistance to the insurgents, the KHAD Afghan security service, under leader Mohammad Najibullah, carried out (according to the Mitrokhin archives and other sources) a large number of operations against Pakistan. In 1987, 127 incidents resulted in 234 deaths in Pakistan. In April 1988, an ammunition depot outside the Pakistani capital of Islamabad was blown up killing 100 and injuring more than 1000 people. The KHAD and KGB were suspected in the perpetration of these acts.[50]

Pakistan took in millions of Afghan refugees (mostly Pashtun) fleeing the Soviet occupation. Although the refugees were controlled within Pakistan's largest province, Balochistan under then-martial law ruler General Rahimuddin Khan, the influx of so many refugees - believed to be the largest refugee population in the world[51] — into several other regions.

All of this had a heavy impact on Pakistan and its effects continue to this day. Pakistan, through its support for the mujahideen, played a significant role in the eventual withdrawal of Soviet military personnel from Afghanistan.

Pakistan went to the point of maintaining a limited air war against Afghan/Soviet forces.[52] [53]

[edit] April 1985-January 1987: Exit strategy

The first step of the exit strategy was to transfer the burden of fighting the mujahideen to the Afghan armed forces, with the aim of preparing them to operate without Soviet help. During this phase, the Soviet contingent was restricted to supporting the DRA forces by providing artillery, air support and technical assistance, though some large-scale operations were still carried out by Soviet troops.

Under Soviet guidance, the DRA armed forces were built up to an official strength of 302,000 in 1986. To minimize the risk of a coup d'état, they were divided into different branches, each modeled on its Soviet counterpart. The ministry of defense forces numbered 132,000, the ministry of interior 70,000 and the ministry of state security (KHAD) 80,000. However, these were theoretical figures: in reality each service was plagued with desertions, the army alone suffering 32,000 per year.

The decision to engage primarily Afghan forces was taken by the Soviets, but was resented by the PDPA, who viewed the departure of their protectors without enthusiasm. In May 1987 a DRA force attacked well-entrenched mujahideen positions in the Arghandab District, but the mujahideen held their ground, and the attackers suffered heavy casualties.[54] In the spring of 1986, an offensive into Paktia Province briefly occupied the mujahideen base at Zhawar only at the cost of heavy losses.[55] Meanwhile, the mujahideen benefited from expanded foreign military support from the United States, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and other Muslim nations. The US tended to favor the Afghan resistance forces led by Ahmed Shah Massoud, and US support for Massoud's forces increased considerably during the Reagan administration in what US military and intelligence forces called "Operation Cyclone." Primary advocates for supporting Massoud included two Heritage Foundation foreign policy analysts, Michael Johns and James A. Phillips, both of whom championed Massoud as the Afghan resistance leader most worthy of US support under the Reagan Doctrine.[56][57][58]

[edit] January 1987-February 1989: Withdrawal

In the last phase, Soviet troops prepared and executed their withdrawal from Afghanistan. They hardly engaged in offensive operations at all, and were content to defend against mujahideen raids.[citation needed]

The one exception was Operation Magistral, a successful sweep that cleared the road between Gardez and Khost. This operation did not have any lasting effect, but it allowed the Soviets to symbolically end their presence with a victory.[59]

The first half of the Soviet contingent was withdrawn from May 15 to August 16, 1988 and the second from November 15 to February 15, 1989. The withdrawal was generally executed peacefully, as the Soviets had negotiated ceasefires with local mujahideen commanders, in order to ensure a safe passage.[60] Now fighting alone, the DRA forces were obliged to abandon some provincial capitals, and it was widely believed that they would not be able to resist the mujahideen for long. However, in the spring of 1989 DRA forces inflicted a sharp defeat on the mujahideen at Jalalabad, and as a result, the war remained stalemated.

The government of President Karmal, a puppet regime, was largely ineffective. It was weakened by divisions within the PDPA and the Parcham faction, and the regime's efforts to expand its base of support proved futile. Moscow came to regard Karmal as a failure and blamed him for the problems. Years later, when Karmal’s inability to consolidate his government had become obvious, Mikhail Gorbachev, then General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, said:

- The main reason that there has been no national consolidation so far is that Comrade Karmal is hoping to continue sitting in Kabul with our help.

In November 1986, Mohammad Najibullah, former chief of the Afghan secret police (KHAD), was elected president and a new constitution was adopted. He also introduced in 1987 a policy of "national reconciliation," devised by experts of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and later used in other regions of the world. Despite high expectations, the new policy neither made the Moscow-backed Kabul regime more popular, nor did it convince the insurgents to negotiate with the ruling government.

Informal negotiations for a Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan had been underway since 1982. In 1988, the governments of Pakistan and Afghanistan, with the United States and Soviet Union serving as guarantors, signed an agreement settling the major differences between them known as the Geneva Accords. The United Nations set up a special Mission to oversee the process. In this way, Najibullah had stabilized his political position enough to begin matching Moscow's moves toward withdrawal. On July 20, 1987, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country was announced. The withdrawal of Soviet forces was planned out by Lt. Gen. Boris Gromov, who, at the time, was the commander of the 40th Army.

Among other things the Geneva accords identified the US and Soviet non-intervention in the internal affairs of Pakistan and Afghanistan and a timetable for full Soviet withdrawal. The agreement on withdrawal held, and on February 15, 1989, the last Soviet troops departed on schedule from Afghanistan.

[edit] Consequences of the war

[edit] International reaction

US President Jimmy Carter claimed that the Soviet incursion was "the most serious threat to peace since the Second World War." Carter later placed a trade embargo against the Soviet Union on shipments of commodities such as grain and weapons. The increased tensions, as well as the anxiety in the West about tens of thousands of Soviet troops being in such proximity to oil-rich regions in the Persian Gulf, effectively brought about the end of détente.

The international diplomatic response was severe, ranging from stern warnings to a US-led boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. The invasion, along with other events, such as the Iranian revolution and the US hostage stand-off that accompanied it, the Iran–Iraq War, the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the escalating tensions between Pakistan and India, contributed to making the Middle East an extremely violent and turbulent region during the 1980s. The Non-Aligned Movement was sharply divided between those that believed the Soviet deployment to be legal and others who considered the deployment an illegal invasion. Among the Warsaw Pact countries, the intervention was condemned only by Romania. [61]

[edit] Soviet personnel strengths and casualties

Between December 25, 1979 and February 15, 1989, a total of 620,000 soldiers served with the forces in Afghanistan (though there were only 80,000-104,000 serving at one time): 525,000 in the Army, 90,000 with border troops and other KGB sub-units, 5,000 in independent formations of MVD Internal Troops, and police forces. A further 21,000 personnel were with the Soviet troop contingent over the same period doing various white collar and blue collar jobs.

The total irrecoverable personnel losses of the Soviet Armed Forces, frontier, and internal security troops came to 14,453. Soviet Army formations, units, and HQ elements lost 13,833, KGB sub-units lost 572, MVD formations lost 28, and other ministries and departments lost 20 men. During this period 417 servicemen were missing in action or taken prisoner; 119 of these were later freed, of whom 97 returned to the USSR and 22 went to other countries.

There were 469,685 sick and wounded, of whom 53,753 or 11.44 percent, were wounded, injured, or sustained concussion and 415,932 (88.56 percent) fell sick. A high proportion of casualties were those who fell ill. This was because of local climatic and sanitary conditions, which were such that acute infections spread rapidly among the troops. There were 115,308 cases of infectious hepatitis, 31,080 of typhoid fever, and 140,665 of other diseases. Of the 11,654 who were discharged from the army after being wounded, maimed, or contracting serious diseases, 92 percent, or 10,751 men, were left disabled.[62]

After the war ended, the Soviet Union published figures of dead Soviet soldiers: the total was 13,836 men, on average, and 1,537 men a year. According to updated figures, the Soviet army lost 14,427, the KGB lost 576, with 28 people dead and missing [63].

Material losses were as follows:

- 118 aircraft

- 333 helicopters

- 147 tanks

- 1,314 IFV/APCs

- 433 artillery guns and mortars

- 1,138 radio sets and command vehicles

- 510 engineering vehicles

- 11,369 trucks and petrol tankers

[edit] Damage to Afghanistan

Over 1 million Afghans were killed.[64] 5 million Afghans fled to Pakistan and Iran, 1/3 of the prewar population of the country. Another 2 million Afghans were displaced within the country. In the 1980s, one out of two refugees in the world was an Afghan.[65]

Along with fatalities were 1.2 million Afghans disabled (mujahideen, government soldiers and noncombatants) and 3 million maimed or wounded (primarily noncombatants).[66]

Irrigation systems, crucial to agriculture in Afghanistan's arid climate, were destroyed by aerial bombing and strafing by Soviet or government forces. In the worst year of the war, 1985, well over half of all the farmers who remained in Afghanistan had their fields bombed, and over one quarter had their irrigation systems destroyed and their livestock shot by Soviet or government troops, according to a survey conducted by Swedish relief experts [67]

The population of Afghanistan's second largest city, Kandahar, was reduced from 200,000 before the war to no more than 25,000 inhabitants, following a months-long campaign of carpet bombing and bulldozing by the Soviets and Afghan communist soldiers in 1987.[68] Land mines had killed 25,000 Afghans during the war and another 10-15 million land mines, most planted by Soviet and government forces, were left scattered throughout the countryside to kill and maim.[69]

A great deal of damage was done to the civilian children population by land mines. A 2005 report estimated 3-4% of the Afghan population were disabled due to Soviet and government land mines. In the city of Quetta, a survey of refugee women and children taken shortly after the Soviet withdrawal found over 80% of the children refugees unregistered and child mortality at 31%. Of children who survived, 67% were severely malnourished, with malnutrition increasing with age.[70]

Critics of Soviet and Afghan government forces describe their effect on Afghan culture as working in three stages: first, the center of customary Afghan culture, Islam, was pushed aside; second, Soviet patterns of life, especially amongst the young, were imported; third, shared Afghan cultural characteristics were destroyed by the emphasis on so-called nationalities, with the outcome that the country was split into different ethnic groups, with no language, religion, or culture in common.[71]

The Geneva accords of 1988, which ultimately led to the withdrawal of the Soviet forces in early 1989, left the Afghan government in ruins. The accords had failed to address adequately the issue of the post-occupation period and the future governance of Afghanistan. The assumption among most Western diplomats was that the Soviet-backed government in Kabul would soon collapse; however, this was not to happen for another three years. During this time the Interim Islamic Government of Afghanistan (IIGA) was established in exile. The exclusion of key groups such as refugees and Shias, combined with major disagreements between the different mujaheddin factions, meant that the IIGA never succeeded in acting as a functional government.[72]

Before the war, Afghanistan was already one of the world's poorest nations. The prolonged conflict left Afghanistan ranked 170 out of 174 in the UNDP's Human Development Index, making the Afghanistan one of the least developed countries in the world.[73]

Once the Soviets withdrew, US interest in Afghanistan ceased. The US decided not to help with reconstruction of the country and instead they handed over the interests of the country to US allies, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. Pakistan quickly took advantage of this opportunity and forged relations with warlords and later the Taliban, to secure trade interests and routes. From wiping out the country's trees through logging practices, which has destroyed all but 2% of forest cover country-wide, to substantial uprooting of wild pistachio trees for the exportation of their roots for therapeutic uses, to opium agriculture, the past ten years have formed permanent ecological and agrarian destruction that Afghanistan may never recover from.[74]

Captain Tarlan Eyvazov, a soldier in the Soviet forces during the war, stated that the Afghan children's future is destined for war. Eyvazoz said, "Children born in Afghanistan at the start of the war... have been brought up in war conditions, this is their way of life." Eyvazov's theory was later strengthened when the Taliban movement developed and formed from orphans or refugee children who were forced by the Soviets to flee their homes and relocate their lives in Pakistan. The swift rise to power, from the young Taliban in 1994, was the result of the disorder and civil war that had warlords running wild because of the complete breakdown of law and order in Afghanistan after the departure of the Soviets.[75]

The CIA World Fact Book reported that as of 2004, Afghanistan still owed $8 billion in bilateral debt, mostly to Russia.[76]

[edit] Civil war

The civil war continued in Afghanistan after the Soviet withdrawal. The Soviet Union left Afghanistan deep in winter with intimations of panic among Kabul officials. The Afghan mujahideen were poised to attack provincial towns and cities and eventually Kabul, if necessary.

Najibullah's regime, though failing to win popular support, territory, or international recognition, was however able to remain in power until 1992. Ironically, until demoralized by the defections of its senior officers, the Afghan Army had achieved a level of performance it had never reached under direct Soviet tutelage. Kabul had achieved a stalemate that exposed the mujahideen's weaknesses, political and military. For nearly three years, Najibullah's government successfully defended itself against mujahideen attacks, factions within the government had also developed connections with its opponents.

According to Russian publicist Andrey Karaulov, the main reason why Najibullah lost power was the fact Russia refused to sell oil products to Afghanistan in 1992 for political reasons (the new Russian government did not want to support the former communists) and effectively triggered an embargo. The defection of General Abdul Rashid Dostam and his Uzbek militia, in March 1992, ultimately undermined Najibullah's control of the state. In April, Najibullah and his communist government fell to the mujahideen, who replaced Najibullah with a new governing council for the country.

Grain production declined an average of 3.5% per year between 1978 and 1990 due to sustained fighting, instability in rural areas, prolonged drought, and deteriorated infrastructure. Soviet efforts to disrupt production in rebel-dominated areas also contributed to this decline. During the withdrawal of Soviet troops, Afghanistan's natural gas fields were capped to prevent sabotage. Restoration of gas production has been hampered by internal strife and the disruption of traditional trading relationships following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

[edit] Ideological impact

The Islamists who fought also believed that they were responsible for the fall of the Soviet Union. Osama bin Laden, for example, was asserting the credit for "the collapse of the Soviet Union ... goes to God and the mujahideen in Afghanistan ... the US had no mentionable role," but "collapse made the US more haughty and arrogant."[77] This lead to the development of a large mercenary force economy which would play a major role in future events in the twenty first century.

[edit] Media and popular culture

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Two books by prominent war correspondent and military history scholar Mark Urban discuss the stalemated nature of the military situation in Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation. See War in Afghanistan, St. Martin’s Press, 1987, and the sequel, War in Afghanistan, St. Martin’s Press, 1990. The second edition discusses the reasons for the Soviet withdrawal.

- ^ An excellent new publication on the war is The Great Gamble: The Soviet War in Afghanistan, by Gregory Feifer, Harper Collins, 2009. Feifer’s research underscores the stalemated character of the war, and explains how Gorbachev sought to withdraw from the conflict because he wanted to concentrate the USSR’s resources on reform at home.

- ^ The Soviet Afghan War: How a Superpower Fought and Lost, by Lester W. Grau, University Press of Kansas, 2002. Despite the wording of the title of his book, Grau’s excellent analysis reinforces the reality that the Soviets and mujahideen were locked in an unbreakable stalemate for the duration of the war. Grau’s thesis is that by incessantly pressuring the Soviet army’s logistical capabilities (control of the roads and airborne transportation), the mujahideen insured that they could resist the Soviet occupation indefinitely.

- ^ Compound War Case Study: The Soviets in Afghanistan, by Robert F. Baumann, Army Command and General Staff School (CGSS), 2001. This article, which is widely available on the Internet, is an excellent study of the multiple factors that influenced the Soviet decision to withdraw from Afghanistan. Baumann’s thesis is that the Soviets maintained an indecisive military advantage over the insurgents throughout the conflict, but that this advantage was offset by sharp Soviet reversals in other (i.e., non-military) dimensions of the conflict, such as economics, ideology, politics, and diplomacy.

- ^ a b J. Bruce Amstutz.(1994); Afghanistan; The First Five Years of Soviet Occupation; ISBN 0 788111-11-6 [1], p.155

- ^ "Timeline: Soviet war in Afghanistan". BBC News. Published February 17, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ Rubin, Barnett R. The Fragmentation of Afghanistan. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995. p. 20.

- ^ Valenta, Jiri (1980). “From Prague to Kabul: The Soviet Style of Invasion”.

- ^ Goldman, Minton (1984). Soviet Military Intervention in Afghanistan: Roots & Causes.

- ^ Bradsher, Henry S. Afghanistan and the Soviet Union. Durham: Duke Press Policy Studies, 1983. p. 72-73

- ^ Hilali, A. Z. “The Soviet Penetration into Afghanistan and the Marxist Coup.” The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 18, no. 4 (2005): 673-716, p. 709.

- ^ Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and Confrontation. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institute, 1994. p. 986.

- ^ a b The April 1978 Coup d'etat and the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan - Library of congress country studies(Retrieved February 4, 2007)

- ^ Pakistan's Support of Afghan Islamists, 1975-79 - Library of congress country studies(Retrieved February 4, 2007)

- ^ Bennett Andrew(1999); A bitter harvest: Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and its effects on Afghan political movements(Retrieved February 4, 2007)

- ^ Kabul's prison of death BBC, February 27, 2006

- ^ a b Kaplan, Robert D.(2001), Soldiers of God : With Islamic Warriors in Afghanistan and Pakistan, New York, Vintage Departures, ISBN 1-4000-3025-0, p.115

- ^ a b Goodson, Larry P.(2001); Afghanistan's Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics, and the Rise of the Taliban; University of Washington Press; ISBN-13 978-0295980508; p. 56-57

- ^ Ismail Khan, Herat, and Iranian Influence by Thomas H. Johnson, Strategic Insights, Volume III, Issue 7 (July 2004)

- ^ "The CIA's Intervention in Afghanistan (Interview with Zbigniew Brzezinski)". Le Nouvel Observateur. 1998-01-21. http://www.globalresearch.ca/articles/BRZ110A.html. Retrieved on 2008-03-15.

- ^ Bergen, Peter, Holy War Inc., Free Press, (2001), p.68

- ^ Interview with Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski-(13/6/97).

- ^ Walker, Martin (1994). The Cold War - A History. Toronto, Canada: Stoddart.

- ^ Coll, Steven. Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001. New York: Penguin Books, 2004. p. 48.

- ^ (Russian) ДО ШТУРМА ДВОРЦА АМИНА

- ^ Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and Confrontation. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institute, 1994. p. 1017-1018

- ^ Arnold, Anthony. Afghanistan’s Two-Party Communism: Parcham and Khalq. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1983. p. 96.

- ^ Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and Confrontation. Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institute, 1994. p. 1017.

- ^ The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan in 1979: Failure of Intelligence or of the Policy Process? - Page 7

- ^ Ye. I. Malashenko, Movement to contact and commitment to combat of reserve fronts, Military Thought (military-theoretical journal of the Russian Ministry of Defense), April-June 2004

- ^ Fisk, Robert. The Great War for Civilisation: the Conquest of the Middle East. London: Alfred Knopf, 2005. pp. 40-41 ISBN 1-84115-007-X.

- ^ Roy, Olivier (1990). Islam and resistance in Afghanistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 118. ISBN 0 521 39700 6.

- ^ Russian General Staff, Grau & Gress, The Soviet-Afghan War, p. 18

- ^ Grau, Lester (March 2004). "The Soviet-Afghan war: a superpower mired in the mountains". Foreign Military Studies Office Publications. http://leav-www.army.mil/fmso/documents/miredinmount.htm. Retrieved on 2007-09-15.

- ^ Russian General Staff, Grau & Gress, The Soviet-Afghan War, p. 26

- ^ Yousaf, Mohammad & Adkin, Mark (1992). Afghanistan, the bear trap: the defeat of a superpower. Casemate. pp. 159. ISBN 0 9711709 2 4.

- ^ Roy. Islam and resistance in Afghanistan. pp. 191.

- ^ "How the CIA created Osama bin Laden". Green Left Weekly. 2001-09-19. http://www.greenleft.org.au/2001/465/25199. Retrieved on 2007-01-09.

- ^ "1986-1992: CIA and British Recruit and Train Militants Worldwide to Help Fight Afghan War". Cooperative Research History Commons. http://www.cooperativeresearch.org/context.jsp?item=a86operationcyclone. Retrieved on 2007-01-09.

- ^ [2] Sageman, Marc Understanding Terror Networks, chapter 2, University of Pennsylvania Press, May 1, 2004

- ^ "Did the U.S. "Create" Osama bin Laden?(2005-01-14)". US Department of State. http://usinfo.state.gov/media/Archive/2005/Jan/24-318760.html. Retrieved on 2007-03-28.

- ^ a b c d The Path to Victory and Chaos: 1979-92 - Library of Congress country studies(Retrieved Thursday 31, 2007)

- ^ The siege was ended only in November 1987 through the conduct of Operation Magistal'

- ^ Eduardo Real: "Zbigniew Brzezinski, Defeated by his Success"

- ^ Crile, George (2003). Charlie Wilson's War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0871138549.

- ^ Kepel, Gilles, Jihad, Belknap, (2002), p.143

- ^ Maley, William and Amin Saikal, The Soviet Withdrawal from AfghanistanCambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, p.16

- ^ Encarta Encyclopedia:Soviet-Afgan War

- ^ Kepel, Jihad, (2002), p.143-4

- ^ Kaplan, Soldiers of God, p.12

- ^ Amnesty International file on Afghanistan URL Accessed March 22, 2006

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/1987/05/02/world/afghans-down-a-pakistani-f-16-saying-fighter-jet-crossed-border.html

- ^ http://www.pakdef.info/pakmilitary/airforce/war/indexafghanwar.html

- ^ Urban, War in Afghanistan, p. 219

- ^ Grau, Lester & Jalali, Ali Ahmad. "The campaign for the caves: the battles for Zhawar in the Soviet-Afghan War". GlobalSecurity.org. http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/2001/010900-zhawar.htm. Retrieved on 2007-03-29.

- ^ "Winning the Endgame in Afghanistan," by James A. Phillips, Heritage Foundation Backgrounder #181, May 18, 1992.

- ^ "Charlie Wilson's War Was Really America's War," by Michael Johns, January 19, 2008.

- ^ "Think tank fosters bloodshed, terrorism," The Daily Cougar, August 25, 2008.

- ^ Isby, War in a distant country, p.47

- ^ Urban, War in Afghanistan, p. 251

- ^ Nicolae Andruta Ceausescu

- ^ Krivosheev, G. F. (1993). Combat Losses and Casualties in the Twentieth Century. London, England: Greenhill Books.

- ^ Russia and the USSR in wars XX century. -- Moscow: OLMA-Press, 2001. -- S. 537.

- ^ Death Tolls for the Major Wars ...

- ^ Kaplan, Soldiers of God (2001) (p.11)

- ^ Hilali, A. (2005). US-Pakistan relationship: Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co. (p.198)

- ^ Kaplan, Soldiers of God (2001) (p.11)

- ^ Kaplan, Soldiers of God (2001) p.188

- ^ "MINES PUT AFGHANS IN PERIL ON RETURN," By ROBERT PEAR, New York Times, Aug 14, 1988. p. 9 (1 page)

- ^ Zulfiqar Ahmed Bhutta, H. (2002). Children of war: the real casualties of the Afghan conflict. Retrieved December 11, 2007

- ^ Hauner, M. (1989). Afghanistan and the Soviet Union: Collision and transformation. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. (p.40)

- ^ Barakat, S. (2004). Reconstructing war-torn societies: Afghanistan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan (p.5)

- ^ Barakat, S. (2004). Reconstructing war-torn societies: Afghanistan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan (p.7)

- ^ Panetta L. (2007) Collateral damage and the uncertainty of Afghanistan...[3] San Francisco: OpticalRealities. Retrieved December 11, 2007

- ^ Kirby, A. (2003). War 'has ruined Afghan environment.' Retrieved November 27, 2007, from [4], Zulfiqar Ahmed Bhutta, H. (2002). Children of war: the real casualties of the Afghan conflict. Retrieved December 11, 2007, from [5]

- ^ USSR aid to Afghanistan worth $8 billion

- ^ Messages to the World, 2006, p.50. (March 1997 interview with Peter Arnett

[edit] Further reading

- Muhammad Ayub,An Army It's Role and Rule (A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil 1947-1999), ISBN 0-8059-9594-3

- The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB, Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, Basic Books, 1999, ISBN 0-465-00310-9

- Kurt Lohbeck, Holy War, Unholy Victory: Eyewitness to the CIA's Secret War in Afghanistan, Regnery Publishing (1993), ISBN 0-89526-499-4

- George Crile, Charlie Wilson's War: the extraordinary story of the largest covert operation in history, Atlantic Monthly Press 2003, ISBN 0-87113-851-4

- Robert D. Kaplan, Soldiers of God: With Islamic Warriors in Afghanistan and Pakistan, ISBN 1-4000-3025-0

- Mark Galeotti, Afghanistan: the Soviet Union's last war, ISBN 0-71468-242-X

- John Prados, Presidents' Secret Wars, ISBN 1-56663-108-4

- Kakar, M. Hassan, Afghanistan: The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979-1982, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995. (free online access courtesy of UCP)

- Borovik, Artyom, The Hidden War: A Russian Journalist's Account of the Soviet War in Afghanistan, ISBN 0-8021-3775-X

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Soviet war in Afghanistan |

- The Art of War project, dedicated to the soldiers of the recent wars, set up by the veterans of the Afghan war. Has Russian and English versions

- "Afganvet" (Russian: "Афганвет") — USSR/Afghanistan war veterans community

- [7]The illustrations of Kills of Pakistan Air Force F-16s During Afghan War

- Casualty figures

- U.N resolution A/RES/37/37 over the Intervention in the Country

- Afghanistan Country Study (details up to 1985)

- A highly detailed description of the Coup de Main in Kabul 1979

- The Take-Down of Kabul: An Effective Coup de Main

- Soviet Afghan War Documentary. An ITN & Pro Video production. Wars In Peace — Afghanistan (1990). Available on Google Video

- One Day in Soviet-Afghan War — Documentary (66 min), August 1988

- Primary Sources on the Invasion Compiled by The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

- 'Pain and Hope of Afghanistan', 1979-1989, Documentary with English subtitles

- Soviet Airborne: Equipment and Weapons used by the Soviet Airborne (VDV) and DShB from 1979 to 1991. English only.

|

||||||||