Planck units

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Planck units are units of measurement named after the German physicist Max Planck, who first proposed them in 1899. They are an example of natural units, i.e. units of measurement designed so that certain fundamental physical constants are normalized to 1. In Planck units, the constants thus normalized are:

- the gravitational constant, G;

- The reduced Planck constant, ħ;

- the speed of light in a vacuum, c;

- the Coulomb force constant,

- Boltzmann's constant, kB (or simply k).

Each of these constants can be associated with at least one fundamental physical theory: c with special relativity, G with general relativity and Newtonian gravity, ħ with quantum mechanics, ε0 with electrostatics, and k with statistical mechanics and thermodynamics. Planck units have profound significance for theoretical physics since they simplify several recurring algebraic expressions of physical law by nondimensionalization. They are particularly relevant in research on unified theories such as quantum gravity.

Contents |

[edit] Base Planck units

All systems of measurement feature base units: in the International System of Units (SI), for example, the base unit of length is the meter. In the system of Planck units, the Planck base unit of length is known simply as the Planck length, the base unit of time is the Planck time, and so on. These units are derived from the five fundamental physical constants in Table 1, which are arranged in Table 2 so as to cancel out the unwanted dimensions, leaving only the dimension appropriate to each unit. (Like all systems of natural units, Planck units are an instance of dimensional analysis.)

| Constant | Symbol | Dimension | Value in SI units with uncertainties[1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed of light in vacuum | c | LT −1 | 299 792 458 m/s |

| Gravitational constant | G | L3M−1T −2 | 6.674 28(67) × 10−11 m3 kg−1 s−2 |

| reduced Planck's constant |  where h is Planck's constant where h is Planck's constant |

L2 M T −1 | 1.054 571 628(53) × 10−34 J s |

| Coulomb force constant |  where ε0 is the permittivity of free space where ε0 is the permittivity of free space |

L3MT −2Q−2 | 8 987 551 787.368 1764 N m2 C−2 |

| Boltzmann constant | k | L2MT −2Θ−1 | 1.380 6504(24) × 10−23 J K−1 |

Key: L = length, T = time, M = mass, Q = electric charge, Θ = temperature. The values given without uncertainties are exact due to the definitions of the metre and the ampere.

| Name | Dimension | Expressions | SI equivalent with uncertainties[1] | Other equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

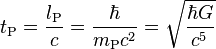

| Planck length | Length (L) |  |

1.616 252(81) × 10−35 m | |

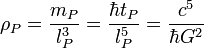

| Planck mass | Mass (M) |  |

2.176 44(11) × 10−8 kg | 1.220 862(61)× 1019 GeV/c2 |

| Planck time | Time (T) |  |

5.391 24(27) × 10−44 s | |

| Planck charge | Electric charge (Q) |  |

1.875 545 870(47) × 10−18 C | 11.706 237 6398(40) e |

| Planck temperature | Temperature (Θ) |  |

1.416 785(71) × 1032 K |

By setting to unity the five fundamental constants in Table 1, the base units of length, mass, time, charge, and temperature shown in Table 2 also acquire the value unity. This may be expressed in non-dimensional terms as follows:

Non-dimensional units such as these require careful use. As observed by Paul Wesson, in reference to G=c=1:

"Mathematically it is an acceptable trick which saves labour. Physically it represents a loss of information and can lead to confusion."[2]

[edit] Derived Planck units

In any system of measurement, units for many physical quantities can be derived from base units. Table 3 offers a sample of derived Planck units, some of which in fact are seldom used. As with the base units, their use is mostly confined to theoretical physics because most of them are too large or too small for empirical or practical use and there are large uncertainties in their values (see Discussion and Uncertainties in values below).

Table 3: Derived Planck units

| Name | Dimensions | Expression | Approximate SI equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Planck area | Area (L2) |  |

2.61223 × 10–70 m2 |

| Planck volume | Volume (L3) |  |

4.22419 × 10–105 m3 |

| Planck momentum | Momentum (LMT–1) |  |

6.52485 kg m/s |

| Planck energy | Energy (L2MT–2) |  |

1.9561 × 109 J |

| Planck force | Force (LMT–2) |  |

1.21027 × 1044 N |

| Planck power | Power (L2MT–3) |  |

3.62831 × 1052 W |

| Planck density | Density (L–3M) |  |

5.15500 × 1096 kg/m3 |

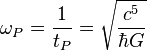

| Planck angular frequency | Frequency (T–1) |  |

1.85487 × 1043 s−1 |

| Planck pressure | Pressure (L–1MT–2) |  |

4.63309 × 10113 Pa |

| Planck current | Electric current (QT–1) |  |

3.4789 × 1025 A |

| Planck voltage | Voltage (L²MT–2Q–1) |  |

1.04295 × 1027 V |

| Planck impedance | Resistance (L2MT–1Q–2) |  |

29.9792458 Ω |

[edit] Planck units simplify key equations

Physical quantities that have different dimensions (such as time and length) cannot be equated even if they are numerically equal (1 second is not the same as 1 metre). In theoretical physics, however, this scruple can be set aside, by a process called nondimensionalization. Table 4 shows how Planck units, by setting the numerical values of five fundamental constants to unity, nondimensionalizes and simplifies many fundamental equations of physics.

| Usual form | Nondimensionalized form | |

|---|---|---|

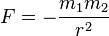

| Newton's law of universal gravitation |  |

|

| Einstein field equations in general relativity |  |

|

| Mass–energy equivalence in special relativity |  |

|

| Thermal energy per particle per degree of freedom |  |

|

| Boltzmann's principle for entropy |  |

|

| Planck's relation for energy and angular frequency |  |

|

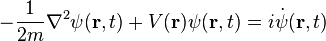

| Schrödinger's equation |  |

|

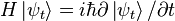

| Hamiltonian form of Schrödinger's equation |  |

|

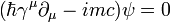

| Covariant form of the Dirac equation |  |

|

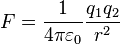

| Coulomb's law |  |

|

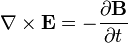

| Maxwell's equations |

|

|

[edit] Other possible normalizations

As already stated above, Planck units are derived by "normalizing" the numerical values of certain fundamental constants to 1. These normalizations are neither the only ones possible nor necessarily the best. Moreover, the choice of what factors to normalize, among the factors appearing in the fundamental equations of physics, is not evident, and the values of the Planck units are sensitive to this choice.

Possible alternative normalizations include:

- The permittivity of free space ε0 = 1.

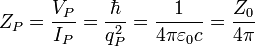

- Planck normalized to 1 the Coulomb force constant 1/(4πε0) (as does the cgs system of units). This sets the Planck impedance, ZP equal to Z0/4π, where Z0 is the characteristic impedance of free space. On the other hand, ε0 = 1:

- Equates ZP and Z0;

- Eliminate 4π from the nondimensionalized form of Maxwell's equations;

- Introduce a factor of (4π)-1 into the nondimensionalized form of Coulomb's law.

- Boltzmann's constant k = 2. This would:

- Remove the factor of 1/2 in the nondimensionalized equation for the thermal energy per particle per degree of freedom;

- Introduce a factor of 2 into the nondimensionalized form of Boltzmann's entropy formula;

- Not affect the value of any base or derived Planck unit other than the Planck temperature.

The factor 4π is ubiquitous in theoretical physics because it equals the surface area of a unit sphere, and appears in the formulae for the surface area and volume of any three dimensional sphere. For example, gravitational and electrostatic fields produced by point charges have spherical symmetry (Barrow 2002: 214-15). The 4πr2 appearing in the denominator of Coulomb's law, for example, follows from the flux of an electrostatic field being distributed uniformly on the surface of a sphere. If space had more dimensions, the factor 4π would have to be changed.

In 1899, Newton's law of universal gravitation was still seen as fundamental, rather than as a convenient approximation holding for "small" velocities and distances, as general relativity was to inform us starting in 1915. Hence Planck normalized to 1 the gravitational constant G in Newton's law. In theories emerging after 1899, G nearly always appears multiplied by 4π or a small integer multiple thereof. Hence a fundamental choice that has to be made when designing a system of natural units is which, if any, instances of 4nπ appearing in the equations of physics are to be eliminated via the normalization. 4nπG = 1 for some value of n:

- n=1. This would eliminate the factor 4πG appearing in:

- Gauss's law for gravity, Φg = −4πGM;

- The characteristic impedance of gravitational radiation in free space, Z0 = 4πG/c.[3] The c in the denominator stems from the general relativity prediction that gravitational radiation propagates at the same speed as electromagnetic radiation;

- The gravitoelectromagnetic (GEM) equations, which hold in weak gravitational fields or reasonably flat space-time. These equations have the same form as Maxwell's equations (and the Lorentz force equation) of electromagnetism, with mass density replacing charge density, and with 1/(4πG) replacing ε0.

- n=2. This would eliminate 8πG from the Einstein field equations, Einstein-Hilbert action, Friedmann equations, and the Poisson equation for gravitation. Planck units modified so that 8πG = 1 are known as reduced Planck units, because the Planck mass is divided by

- n=4. This would eliminate the constant c4/(16πG) from the Einstein-Hilbert action. The Einstein field equations with cosmological constant Λ becomes Rμν − Λgμν = (Rgμν − Tμν)/2.

Hence a substantial body of physical theory discovered since Planck (1899) suggests normalizing to 1 not G but 4nπG, for one of n = 1, 2, or 4. However, doing so would introduce a factor of 1/(4nπ) into the nondimensionalized form of the law of universal gravitation.

[edit] Uncertainties in values

Planck units are clearly defined in terms of fundamental constants in Table 2 and yet, relative to other units of measurement such as SI, the values of those units are only known approximately. This is mostly due to uncertainty in the value of the gravitational constant G.

Today the value of the speed of light c in SI units is not subject to measurement error, because the SI base unit of length, the metre, is now defined as the length of the path travelled by light in vacuum during a time interval of 1/299 792 458 of a second. Hence the value of c is now exact by definition, and contributes no uncertainty to the SI equivalents of the Planck units. The same is true of the value of the vacuum permittivity ε0, due to the definition of ampere which sets the vacuum permeability μ0 to 4π × 10−7 H/m and the fact that μ0ε0 = 1/c2. The numerical value of the reduced Planck constant ℏ has been determined experimentally to 50 parts per billion, while that of G has been determined experimentally to no better than 1 part in 10000.[1] G appears in the definition of almost every Planck unit in Tables 2 and 3. Hence the uncertainty in the values of the Table 2 and 3 SI equivalents of the Planck units derives almost entirely from uncertainty in the value of G. (The propagation of the error in G is a function of the exponent of G in the algebraic expression for a unit. Since that exponent is ±1⁄2 for every base unit other than Planck charge, the relative uncertainty of each base unit is about one half that of G. This is indeed the case; according to CODATA, the experimental values of the SI equivalents of the base Planck units are known to about 1 part in 20,000.)

[edit] Discussion

Physicists sometimes humorously refer to Planck units as "God's units", as Planck units are free of arbitrary anthropocentricity. Unlike the meter and second, which exist as fundamental units in the SI system for historical reasons, the Planck length and Planck time are conceptually linked at a fundamental physical level.

Some Planck units are suitable for measuring quantities that are familiar from daily experience. For example:

- 1 Planck mass is about 22 micrograms;

- 1 Planck momentum is about 6.5 kg m/s;

- 1 Planck energy is about 500 kWh;

- 1 Planck charge is slightly more than 11 elementary charges;

- 1 Planck impedance is very nearly 30 ohms.

However, most Planck units are many orders of magnitude too large or too small to be of any empirical and practical use, so that Planck units as a system are really only relevant to theoretical physics. In fact, 1 Planck unit is often the largest or smallest value of a physical quantity that makes sense given the current state of physical theory. For example:

- a speed of 1 Planck length per Planck time is the speed of light in a vacuum, the maximum possible speed in special relativity;[4]

- our understanding of the Big Bang begins with the Planck Epoch, when the universe grew older and larger than about 1 Planck time and 1 Planck length, at which time it cooled below about 1 Planck temperature and quantum theory as presently understood becomes applicable. Understanding the universe when it was less than 1 Planck time old requires a theory of quantum gravity, incorporating quantum effects into general relativity. Such a theory does not yet exist;

- at a Planck temperature of 1, all symmetries broken since the early Big Bang would be restored, and the four fundamental forces of contemporary physical theory would become one force.

Relative to the Planck Epoch, the universe today looks extreme when expressed in Planck units, as in this set of approximations (see for example):[5] and[6]

Table 5: Today's universe in Planck units

| Feature of present-day universe | Approximate number of Planck units |

|---|---|

| Age | 8.0 × 1060 tP (4.3 × 1017 seconds) |

| Diameter | 5.4 x 1061 lP (8.7 × 1026 meters) |

| Mass | Roughly 1060 mP (3 × 1052 kilograms, only counting stars); 1080 protons (sometimes known as the Eddington number) |

| Temperature | 1.9 × 10−32 TP (temperature of the cosmic microwave background radiation, 2.725 kelvins) |

The recurrence of the large number 1060 in the above table is a coincidence that intrigues some theorists. It is an example of the kind of large numbers coincidence that led theorists such as Eddington and Dirac to develop alternative physical theories. Theories derived from such coincidences are often dismissed by mainstream physicists as 'numerology'. Natural units however can and do help physicists reframe physical questions that are accepted among conventional theorists. An example of such reframing is the following passage by Frank Wilczek:

We see that the question it [the smallness of N = GNmp2/ħc ≈ 3 × 10−39] poses is not, "Why is gravity so feeble?" but rather, "Why is the proton's mass so small?" For in natural (Planck) units, the strength of gravity simply is what it is, a primary quantity, while the proton's mass is the tiny number √N.

[edit] History

Natural units began in 1881, when George Johnstone Stoney derived units of length, time, and mass, now named Stoney units in his honor, by normalizing G, c, and the electron charge e to 1. (Stoney was also the first to hypothesize that electric charge is quantized and hence to see the fundamental character of e.) Max Planck first set out the base units (qP excepted) later named in his honor, in a paper presented to the Prussian Academy of Sciences in May 1899.[7][8] That paper also includes the first appearance of a constant named b, and later called h and named after him. The paper gave numerical values for the base units, in terms of the metric system of his day, that were remarkably close to those in Table 2. We are not sure just how Planck came to discover these units because his paper gave no algebraic details. But he did explain why he valued these units as follows:

...ihre Bedeutung für alle Zeiten und für alle, auch außerirdische und außermenschliche Kulturen notwendig behalten und welche daher als »natürliche Maßeinheiten« bezeichnet werden können... ...These necessarily retain their meaning for all times and for all civilizations, even extraterrestrial and non-human ones, and can therefore be designated as "natural units"...

[edit] Planck units and the invariant scaling of nature

Some theorists (such as Dirac and Milne) have conjectured that physical "constants" might actually change over time and they have devised cosmologies that allow for these changes (e.g. Dirac's Large Numbers Hypothesis). Such cosmologies have not gained mainstream acceptance and yet there is still considerable, scientific interest in the possibility that physical 'constants' might change. It is a possibility that challenges even the most brilliant minds and it raises questions that seem to admit different answers. One such question is this: if a dimensionful physical constant such as the speed of light did change, would we be able to notice it? George Gamow argued in his book Mr. Tompkins in Wonderland that any change in a dimensionful physical constant, such as the speed of light in a vacuum, would result in obvious changes. However, as shown in Table 2, Planck units are derived from ratios of dimensionful physical constants. Planck units therefore cannot be used to measure changes in those constants since the units themselves would change. If for example the speed of light c, were somehow suddenly cut in half and changed to c/2 then the Planck length would increase by a factor of 2√2 and Planck time would increase by a factor of 4√2. Measured in Planck units therefore, the new speed of light would be measured as 1 new Plank length per 1 new Planck time - which is no different to the old measurement. This unvarying aspect of the Planck scale, or of any other set of natural units, leads many theorists to conclude that a change in dimensionful physical constants can only ever show up as a change in dimensionless physical constants. One such dimensionless physical constant is the Fine structure constant. The fine structure constant (denoted α) relates the size of atoms - approximately the Bohr radius (denoted a0) - to physical constants and therefore to Planck units in this way:

,

,

where e2 is the squared elementary charge and me is the mass of the electron. John Barrow has addressed the issue in these terms:

[An] important lesson we learn from the way that pure numbers like α define the world is what it really means for worlds to be different. The pure number we call the fine structure constant and denote by α is a combination of the electron charge, e, the speed of light, c, and Planck's constant, h. At first we might be tempted to think that a world in which the speed of light was slower would be a different world. But this would be a mistake. If c, h, and e were all changed so that the values they have in metric (or any other) units were different when we looked them up in our tables of physical constants, but the value of α remained the same, this new world would be observationally indistinguishable from our world. The only thing that counts in the definition of worlds are the values of the dimensionless constants of Nature. If all masses were doubled in value [including the Planck mass mP] you cannot tell because all the pure numbers defined by the ratios of any pair of masses are unchanged.

– Barrow 2002

There are some experimental physicists who think they have in fact measured a change in the fine structure constant[9] and this has intensified the debate about the measurement of physical constants. According to some theorists[10] there are some very special circumstances in which changes in the fine structure constant can be measured as a change in dimensionful physical constants. Others however reject the possibility of measuring a change in dimensionful physical constants under any circumstance.[11] The difficulty or even the impossibility of measuring changes in dimensionful physical constants has led some theorists to debate with each other whether or not a dimensionful physical constant has any practical significance at all and that in turn leads to questions about which dimensionful physical constants are meaningful.[12]

[edit] See also

- Dimensional analysis

- Physical constants

- Natural units

- zero-point energy

- Planck scale

- Planck particle

- Planck epoch

- Planck length

- Planck time

- Planck force

- doubly special relativity

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ a b c Fundamental Physical Constants from NIST

- ^ 'The application of dimensional analysis to cosmology' Wesson P.S., Space Science Reviews 27 1980 p.117, [1]

- ^ arXiv:0710.1378v4

- ^ Feynman, R. P.; Leighton, R. B.; Sands, M.. "The Special Theory of Relativity". The Feynman Lectures on Physics. 1 "Mainly mechanics, radiation, and heat". Addison-Wesley. p. 15-9. LCCN 63-20717.

- ^ *John D. Barrow, 2002. The Constants of Nature; From Alpha to Omega - The Numbers that Encode the Deepest Secrets of the Universe. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-375-42221-8.

- ^ Frank J. Tipler, 1986. The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford University Press. Harder.

- ^ Planck (1899), p. 479.

- ^ *Tomilin, K. A., 1999, "Natural Systems of Units: To the Centenary Anniversary of the Planck System," 287-96.

- ^ J.K.Webbe et al., 'Further evidence for cosmological evolution of the fine structure constant', Phys.Rev.Lett 82 884 (1999) [2]

- ^ P.C.Davies, T.M.Davis and C.H.Lineweaver, 'Cosmology: Black Holes Constrain Varying Constants', Nature 418 602 (2002)

- ^ M.Duff, 'Comment on time-variation of fundamental constants', ArXiv e-prints (2002) [3]

- ^ M.Duff, O.Okun and G.Veneziano, 'Trialogue on the number of fundamental constants', Journal of High Energy Physics 3:023, ArXiv e-prints (2002) [4]

[edit] References

- Barrow, John D. (2002). The Constants of Nature; From Alpha to Omega - The Numbers that Encode the Deepest Secrets of the Universe. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0375422218. Easier.

- ———; Tipler, Frank J. (1986). The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford: Claredon Press. ISBN 0198519494. Harder.

- Duff, Michael (2002). "Comment on time-variation of fundamental constants". ArΧiv e-prints. arΧiv:hep-th/0208093.

- ———; Okun, L. B.; Veneziano, Gabriele (2002). "Trialogue on the number of fundamental constants". Journal of High Energy Physics 3: 023. doi:. arΧiv:physics/0110060.

- Planck, Max (1899). "Über irreversible Strahlungsvorgänge". Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin 5: 440–480. http://bibliothek.bbaw.de/bibliothek-digital/digitalequellen/schriften/anzeige/index_html?band=10-sitz/1899-1&seite:int=454. Pp. 478-80 contain the first appearance of the Planck base units other than the Planck charge, and of Planck's constant, which Planck denoted by b. a and f in this paper correspond to k and G in this entry.

- Penrose, Roger (2005). The Road to Reality. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Section 31.1. ISBN 0679454438.

- Tomilin, K. A. (1999). Natural Systems of Units: To the Centenary Anniversary of the Planck System. pp. 287–296. http://dbserv.ihep.su/~pubs/tconf99/ps/tomil.pdf.

[edit] External links

- Value of the fundamental constants, including the Planck base units, as reported by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- Sections C-E of collection of resources bear on Planck units. Good discussion of why 8πG should be normalized to 1 when doing general relativity and quantum gravity. Many links.

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||