Timeline of the Big Bang

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Physical cosmology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Universe · Big Bang Age of the Universe Timeline of the Big Bang Ultimate fate of the universe

|

||||||||||||||

This timeline of the Big Bang describes the events according to the widely accepted scientific theory of the Big Bang, using the cosmological time parameter of comoving coordinates.

Observations suggest that the universe as we know it began around 13.7 billion years ago. Since then, the evolution of the universe has passed through three phases. The very early universe, which is still poorly understood, was the split second in which the universe was so hot that particles had energies higher than those currently accessible in particle accelerators on Earth. Therefore, while the basic features of this epoch have been worked out in the big bang theory, the details are largely based on educated guesses.

Following this period, in the early universe, the evolution of the universe proceeded according to known high energy physics. This is when the first protons, electrons and neutrons formed, then nuclei and finally atoms. With the formation of neutral hydrogen, the cosmic microwave background was emitted.

Matter then continued to aggregate into the first stars and ultimately galaxies, quasars, clusters of galaxies and superclusters formed.

There are several theories about the ultimate fate of the universe.

Contents |

The very early universe

All ideas concerning the very early universe (cosmogony) are speculative. As of today no accelerator experiments probe energies of sufficient magnitude to provide any insight into the period. All proposed scenarios differ radically, some examples being: the Hartle-Hawking initial state, string landscape, brane inflation, string gas cosmology, and the ekpyrotic universe. Some of these are mutually compatible, while others are not.

The Planck epoch

- Up to 10–43 seconds after the Big Bang

If supersymmetry is correct, then during this time the four fundamental forces — electromagnetism, weak nuclear force, strong nuclear force and gravitation — all have the same strength, so they are possibly unified into one fundamental force. Little is known about this epoch, although different theories propose different scenarios. General relativity proposes a gravitational singularity before this time, but under these conditions the theory is expected to break down due to quantum effects. Physicists hope that proposed theories of quantum gravitation, such as string theory and loop quantum gravity, will eventually lead to a better understanding of this epoch.

The grand unification epoch

- Between 10–43 seconds and 10–36 seconds after the Big Bang[1]

As the universe expands and cools from the Planck epoch, gravitation begins to separate from the fundamental gauge interactions: electromagnetism and the strong and weak nuclear forces. Physics at this scale may be described by a grand unified theory in which the gauge group of the Standard Model is embedded in a much larger group, which is broken to produce the observed forces of nature. Eventually, the grand unification is broken as the strong nuclear force separates from the electroweak force. This occurs as soon as inflation does. According to some theories, this should produce magnetic monopoles. Unification of the strong and electroweak forces, means that the only particle expected at this time is the Higgs boson[citation needed].

The electroweak epoch

- Between 10–36 seconds and 10–12 seconds after the Big Bang[1]

The temperature of the universe is low enough (1028K) to separate the strong force from the electroweak force (the name for the unified forces of electromagnetism and the weak interaction). This phase transition triggers a period of exponential expansion known as cosmic inflation. After inflation ends, particle interactions are still energetic enough to create large numbers of exotic particles, including W and Z bosons and Higgs bosons.

The inflationary epoch

- Between 10–36 seconds and 10–32 seconds after the Big Bang

The temperature, and therefore the time, at which cosmic inflation occurs is not known for certain. During inflation, the universe is flattened (its spatial curvature is critical) and the universe enters a homogeneous and isotropic rapidly expanding phase in which the seeds of structure formation are laid down in the form of a primordial spectrum of nearly-scale-invariant fluctuations. Some energy from photons becomes virtual quarks and hyperons, but these particles decay quickly. One scenario suggests that prior to cosmic inflation, the universe was cold and empty, and the immense heat and energy associated with the early stages of the big bang was created through the phase change associated with the end of inflation.

Reheating

During reheating, the exponential expansion that occurred during inflation ceases and the potential energy of the inflaton field decays into a hot, relativistic plasma of particles. If grand unification is a feature of our universe, then cosmic inflation must occur during or after the grand unification symmetry is broken, otherwise magnetic monopoles would be seen in the visible universe. At this point, the universe is dominated by radiation; quarks, electrons and neutrinos form.

Baryogenesis

There is currently not enough observational evidence to explain the reason there are more baryons in the universe than antibaryons. In order for this to be explained, the Sakharov conditions must be met at some time after inflation. While scenarios allowing for such conditions have been observed in particle physics experiments, the observed asymmetries are too small to account for the observed asymmetry of the universe.

The early universe

After cosmic inflation ends, the universe is filled with a quark-gluon plasma. From this point onwards the physics of the early universe is better understood, and less speculative.

Supersymmetry breaking

If supersymmetry is a property of our universe, then it must be broken at an energy as low as 1 TeV, the electroweak symmetry scale. The masses of particles and their superpartners would then no longer be equal, which could explain why no superpartners of known particles have ever been observed.

The quark epoch

- Between 10–12 seconds and 10–6 seconds after the Big Bang

In electroweak symmetry breaking, at the end of the electroweak epoch, all the fundamental particles are believed to acquire a mass via the Higgs mechanism in which the Higgs boson acquires a vacuum expectation value. The fundamental interactions of gravitation, electromagnetism, the strong interaction and the weak interaction have now taken their present forms, but the temperature of the universe is still too high to allow quarks to bind together to form hadrons.

The hadron epoch

- Between 10–6 seconds and 1 second after the Big Bang

The quark-gluon plasma which composes the universe cools until hadrons, including baryons such as protons and neutrons, can form. At approximately 1 second after the Big Bang neutrinos decouple and begin travelling freely through space. This cosmic neutrino background, while unlikely to ever be observed in detail, is analogous to the cosmic microwave background that was emitted much later. (See above regarding the quark-gluon plasma, under the String Theory epoch)

The lepton epoch

- Between 1 second and 3 minutes after the Big Bang

The majority of hadrons and anti-hadrons annihilate each other at the end of the hadron epoch, leaving leptons and anti-leptons dominating the mass of the universe. Approximately 3 seconds after the Big Bang the temperature of the universe falls to the point where new lepton/anti-lepton pairs are no longer created and most leptons and anti-leptons are eliminated in annihilation reactions, leaving a small residue of leptons.

The photon epoch

- Between 3 minutes and 380,000 years after the Big Bang

After most leptons and anti-leptons are annihilated at the end of the lepton epoch the energy of the universe is dominated by photons. These photons are still interacting frequently with charged protons, electrons and (eventually) nuclei, and continue to do so for the next 300,000 years.

Nucleosynthesis

- Between 3 minutes and 20 minutes after the Big Bang[2]

During the photon epoch the temperature of the universe falls to the point where atomic nuclei can begin to form. Protons (hydrogen ions) and neutrons begin to combine into atomic nuclei in the process of nuclear fusion. However, nucleosynthesis only lasts for about seventeen minutes, after which time the temperature and density of the universe has fallen to the point where nuclear fusion cannot continue. At this time, there is about three times more hydrogen than helium-4 (by mass) and only trace quantities of other nuclei.

Matter domination: 70,000 years

At this time, the densities of non-relativistic matter (atomic nuclei) and relativistic radiation (photons) are equal. The Jeans length, which determines the smallest structures that can form (due to competition between gravitational attraction and pressure effects), begins to fall and perturbations, instead of being wiped out by radiation free-streaming, can begin to grow in amplitude.

Recombination: 240,000–310,000 years

Hydrogen and helium atoms begin to form and the density of the universe falls. This is thought to have occurred somewhere between 240,000 and 310,000 years after the Big Bang.[3] Hydrogen and helium are at the beginning ionized, i.e. no electrons are bounded to the nuclei which are therefore electrically charged (+1 and +2 respectively). As the universe cools down, the electrons get captured by the ions making them neutral. This process is relatively fast (actually faster for the helium than for the hydrogen) and is known as recombination.[4] At the end of recombination, most of the atoms in the universe are neutral, therefore the photons can now travel freely: the universe has become transparent. The photons emitted right after the recombination, that can therefore travel undisturbed, are those that we see in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. Therefore the CMB is a picture of the universe at the end of this epoch.

Dark ages

Before decoupling occurs most of the photons in the universe are interacting with electrons and protons in the photon-baryon fluid. The universe is opaque or "foggy" as a result. There is light but not light we could observe through telescopes. The baryonic matter in the universe consisted of ionized plasma, and it only became neutral when it gained free electrons during "recombination," thereby releasing the photons creating the CMB. When the photons were released (or decoupled) the universe became transparent. At this point the only radiation emitted is the 21 cm spin line of neutral hydrogen. There is currently an observational effort underway to detect this faint radiation, as it is in principle an even more powerful tool than the cosmic microwave background for studying the early universe .

Structure formation

Structure formation in the big bang model proceeds hierarchically, with smaller structures forming before larger ones. The first structures to form are quasars, which are thought to be bright, early active galaxies, and population III stars. Before this epoch, the evolution of the universe could be understood through linear cosmological perturbation theory: that is, all structures could be understood as small deviations from a perfect homogeneous universe. This is computationally relatively easy to study. At this point non-linear structures begin to form, and the computational problem becomes much more difficult, involving, for example, N-body simulations with billions of particles.

Reionization: 150 million to 1 billion years

The first quasars form from gravitational collapse. The intense radiation they emit reionizes the surrounding universe. From this point on, most of the universe is composed of plasma.

Formation of stars

The first stars, most likely Population III stars, form and start the process of turning the light elements that were formed in the Big Bang (hydrogen, helium and lithium) into heavier elements. However, as of yet there have been no observed Population III stars which leaves their formation a mystery.[5]

Formation of galaxies

Large volumes of matter collapse to form a galaxy. Population II stars are formed early on in this process, with Population I stars formed later.

Johannes Schedler's project has identified a quasar CFHQS 1641+3755 at 12.7 billion light-years away,[6] when the Universe was just 7 percent of its present age.

On July 11, 2007, using the 10 metre Keck II telescope on Mauna Kea, Richard Ellis of the California Institute of Technology at Pasadena and his team found six star forming galaxies about 13.2 billion light years away and therefore created when the universe was only 500 million years old.[7] Only about 10 of these really early objects are currently known.[8]

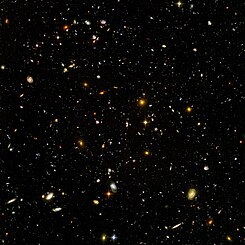

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field shows a number of small galaxies merging to form larger ones, at 13 billion light years, when the Universe was only 5% its current age.[9]

Based upon the emerging science of nucleocosmochronology, the Galactic thin disk of the Milky Way is estimated to have been formed 8.3 ± 1.8 billion years ago.[10]

Formation of groups, clusters and superclusters

Gravitational attraction pulls galaxies towards each other to form groups, clusters and superclusters.

Formation of our solar system: 8 billion years

Finally, objects on the scale of our solar system form. Our sun is a late-generation star, incorporating the debris from many generations of earlier stars, and formed roughly 5 billion years ago, or roughly 8 to 9 billion years after the big bang.

Today: 13.7 billion years

The best current data estimate the age of the universe today as 13.7 billion years since the big bang. Since the expansion of the universe appears to be accelerating, superclusters are likely to be the largest structures that will ever form in the universe. The present accelerated expansion prevents any more inflationary structures entering the horizon and prevents new gravitationally bound structures from forming.

Ultimate fate of the universe

As with interpretations of what happened in the very early universe, advances in fundamental physics are required before it will be possible to know the ultimate fate of the universe with any certainty. Below are some of the main possibilities.

Big freeze: 1014 years and beyond

This scenario is generally considered to be the most likely, as it occurs if the universe continues expanding as it has been. Over a time scale on the order of 1014 years or less, existing stars burn out, stars cease to be created, and the universe goes dark.[11], §IID. Over a much longer time scale in the eras following this, the galaxy evaporates as the stellar remnants comprising it escape into space, and black holes evaporate via Hawking radiation.[11], §III, §IVG. In some grand unified theories, proton decay will convert the remaining interstellar gas and stellar remnants into leptons (such as positrons and electrons) and photons. Some positrons and electrons will then recombine into photons.[11], §IV, §VF. In this case, the universe has reached a high-entropy state consisting of a bath of particles and low-energy radiation. It is not known however whether it eventually achieves thermodynamic equilibrium.[11], §VIB, VID.

Big crunch: 100+ billion years

If the energy density of dark energy were negative or the universe were closed, then it would be possible that the expansion of the universe would reverse and the universe would contract towards a hot, dense state. This is often proposed as part of an oscillatory universe scenario, such as the cyclic model. Current observations suggest that this model of the universe is unlikely to be correct, and the expansion will continue or even accelerate.

Big rip: 200+ billion years

This scenario is possible only if the energy density of dark energy actually increases without limit over time. Such dark energy is called phantom energy and is unlike any known kind of energy. In this case, the expansion rate of the universe will increase without limit. Gravitationally bound systems, such as clusters of galaxies, galaxies, and ultimately the solar system will be torn apart. Eventually the expansion will be so rapid as to overcome the electromagnetic forces holding molecules and atoms together. Finally even atomic nuclei will be torn apart and the universe as we know it will end in an unusual kind of gravitational singularity. In other words, the universe will expand so much that the electromagnetic force holding things together will fall to this expansion, making things fall apart.

Vacuum metastability event

If our universe is in a very long-lived false vacuum, it is possible that the universe will tunnel into a lower energy state. If this happens, all structures will be destroyed instantaneously, without any forewarning.

References

- ^ a b Ryden B: "Introduction to Cosmology", pg. 196 Addison-Wesley 2003

- ^ Detailed timeline of Big Bang nucleosynthesis processes

- ^ Ryden B: "Introduction to Cosmology", pg. 158 Addison-Wesley 2003

- ^ Mukhanov, V: "Physical foundations of Cosmology", pg. 120, Cambridge 2005

- ^ Ferreting Out The First Stars; physorg.com

- ^ APOD: 2007 September 6 - Time Tunnel

- ^ "New Scientist" 14th July 2007

- ^ HET Helps Astronomers Learn Secrets of One of Universe's Most Distant Objects

- ^ APOD: 2004 March 9 - The Hubble Ultra Deep Field

- ^ Eduardo F. del Peloso a1a, Licio da Silva a1, Gustavo F. Porto de Mello and Lilia I. Arany-Prado (2005), "The age of the Galactic thin disk from Th/Eu nucleocosmochronology: extended sample" (Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union (2005), 1: 485-486 Cambridge University Press)

- ^ a b c d A dying universe: the long-term fate and evolution of astrophysical objects, Fred C. Adams and Gregory Laughlin, Reviews of Modern Physics 69, #2 (April 1997), pp. 337–372. Bibcode: 1997RvMP...69..337A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337.

External links

- PBS Online (2000). From the Big Bang to the End of the Universe - The Mysteries of Deep Space Timeline. Retrieved March 24, 2005.

- Schulman, Eric (1997). The History of the Universe in 200 Words or Less. Retrieved March 24, 2005.

- Space Telescope Science Institute Office of Public Outreach (2005). Home of the Hubble Space Telescope. Retrieved March 24, 2005.

- Fermilab graphics (see "Energy time line from the Big Bang to the present" and "History of the Universe Poster")

- Exploring Time from Planck time to the lifespan of the universe

- Astronomers' first detailed hint of what was going on less than a trillionth of a second after time began

- The Universe Adventure

|

||||||||