Thor

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2008) |

Thor (Old Norse: Þórr) is the red-haired and bearded[1][2] god of thunder in Germanic mythology and Germanic paganism, and its subsets: Norse paganism, Anglo-Saxon paganism and Continental Germanic paganism. The god is also recorded in Old English as Þunor, Old Saxon as Thunaer,[3] as Old Dutch and Old High German: Donar, all of which are names deriving from the reconstructed Proto-Germanic name *Þunraz.

Most surviving stories relating to Germanic mythology either mention Thor or center on Thor's exploits. Thor was a much revered god of the ancient Germanic peoples from at least the earliest surviving written accounts of the indigenous Germanic tribes to over a thousand years later in the late Viking Age.

Thor was appealed to for protection on numerous objects found from various Germanic tribes. Miniature replicas of Mjolnir, the weapon of Thor, became a defiant symbol of Norse paganism during the Christianization of Scandinavia.[4][5]

Contents |

[edit] Etymology

Proto-Germanic *Þunraz "thunder" gave rise to Old Norse Þorr, German Donner, Dutch donder as well as Old English Þunor whence Modern English thunder with epenthetic d.

Swedish tordön and Danish and Norwegian torden have the suffix -dön/-den originally meaning "rumble" or "din". The Scandinavian languages also have the word dunder, borrowed from Middle Low German.

[edit] Characteristics

[edit] Family

In the Poetic Edda and Prose Edda, Thor is the son of Odin and the giantess Jörd (Jord, the Earth). His wife is called Sif, and little is known of her except that she has golden hair. With his mistress, the giantess Járnsaxa, Thor had a son Magni and with Sif he had his daughter Thrud. There is nothing in the myths that states the identity of the mother of his son Modi.

The euhemeristic prologue of the Prose Edda also indicates he has a son by Sif named Lóriði, along with an additional 17 generations of descendants, but the prologue was meant to give a plausible explanation on how the Aesir came to be worshiped even though they were not gods in order to appease the Christian church. Thor also has a stepson called Ullr who is a son of Sif. Skáldskaparmál mentions a figure named Hlóra who was Thor's foster mother, corresponding to Lora or Glora from Snorri Sturluson's prologue, although no additional information concerning her is provided in the book.

[edit] Mjolnir

Thor owns a short-handled hammer, Mjolnir, which, when thrown at a target, returns magically to the owner. His Mjolnir also has the power to throw lightning bolts. To wield Mjolnir, Thor wears the belt Megingjord, which boosts the wearer's strength and a pair of special iron gloves, Járngreipr, to lift the hammer. Mjolnir is also his main weapon when fighting giants. The uniquely shaped symbol subsequently became a very popular ornament during the Viking Age and has since become an iconic symbol of Germanic paganism.

[edit] Chariot

Thor travels in a chariot drawn by the goats Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr and with his servant and messenger Þjálfi and with Þjálfi's sister Röskva. The skaldic poem Haustlöng relates that the earth was scorched and the mountains cracked as Thor traveled in his wagon. According to the Prose Edda, when Thor is hungry he can roast the goats for a meal. When he wants to continue his travels, Thor only needs to touch the remains of the goats and they will be instantly restored to full health to resume their duties, assuming that the bones have not been broken.

[edit] Bilskirnir

Bilskirnir, in the kingdom Þrúðheimr or Þrúðvangr, is the hall of Thor in Norse mythology. Here he lives with his wife Sif and their children. According to Grímnismál, the hall is the greatest of buildings and contains 540 rooms, located in Asgard, as are all the dwellings of the gods, in the kingdom of Þrúðheimr (or Þrúðvangar according to Gylfaginning and Ynglinga saga).

[edit] Stories

According to one myth in the Prose Edda, Loki was flying as a hawk one day and was captured by Geirrod. Geirrod, who hated Thor, demanded that Loki bring his enemy (who did not yet have his magic belt and hammer) to Geirrod's castle. Loki agreed to lead Thor to the trap. Grid was a giantess at whose home they stopped on the way to Geirrod's. She waited until Loki left the room, then told Thor what was happening, and gave him her iron gloves and magical belt and staff. Thor killed Geirrod, and all other frost giants he could find (including Geirrod's daughters, Gjálp and Greip).

According to Alvíssmál, Thor's daughter was promised to Alviss, a dwarf. Thor devised a plan to stop Alviss from marrying his daughter: he told Alviss that, because of his small height, he had to prove his wisdom. Alviss agreed, and Thor made the tests last until after the sun had risen - all dwarves turned to stone when exposed to sunlight, so Alviss was petrified.

Thor was once outwitted by a giant king, Útgarða-Loki. The king, using his magic, tricked Thor by racing Thought itself against Thor's fast servant, Þjálfi (nothing being faster than thought, which can leap from land to land, and from time to time, in an instant). Then, Loki (who was with Thor) was challenged by Útgarða-Loki to an eating contest with one of his servants, Logi. Loki lost, eventually. The servant even ate up the trough containing the food. The servant was an illusion of "Wild-Fire", no living thing being able to equal the consumption rate of fire. He called Thor weak when he only lifted the paw of a cat, the cat being the illusion of the Midgard Serpent. Thor was challenged to a drinking contest, and could not empty a horn which was filled not with mead but was connected to the ocean. This action started tidal changes. And here, Thor wrestled an old woman, Elli who was Old Age, something no one could beat, to one knee. Thor left humiliated, but was heartened later when he met a messenger who told him that in fact he had done tremendous deeds worthy of a powerful warrior god, in doing as well as he did with those challenges.

Another noted story involving Thor was the time when Þrymr, King of the Thurse (Giants), stole his hammer, Mjölnir. Thor went to Loki, hoping to find the culprit responsible for the theft, then Loki and Thor went to Freyja for council. Freyja gave Loki the Feather-robe so that he could travel to the land of the giants, to speak to their king. The king admitted to stealing the hammer, and would not give it back unless Freyja gave him her hand in marriage.

Freyja refused when she heard the plan, so the gods decided to think of a way to trick the King. Heimdall suggested dressing up Thor in a bridal gown, so that he could take Freyja's place. Thor at first refused to do such a thing, as it would portray him as a womanly coward, but Loki insisted that he do so or the Giants would attack Asgard, and win it over if he were not to retrieve the hammer in time. Thor reluctantly agreed (in the end), and took Freyja's place.

Odin rode Thor to the land of the Giants, and a celebration ensued. The king noticed a few odd things that his bride was doing; he noted that she ate and drank significantly more than what he would expect from a bride. Loki, who was in disguise as the false Freyja's servant, commented that she rode for eight full nights without food in her eagerness to take his hand. He then asked why his bride's eyes were so terrifying - they seemed to be aglow with fire - again Loki responded with the same lie, saying that she did not sleep for eight full nights in her eagerness for his hand. Then, the giant commanded that the hammer be brought to his wife and placed on her lap. Once it was in Thor's possession, he threw off his disguise and attacked all the giants in the room. Due to the success of this ruse, the giants were careful not to make the same mistake again.

According to the Prose Edda, Thor was to meet his death during Ragnarök at the hands of Jörmungandr. The two mortal enemies were locked in combat and though Thor did defeat the great serpent, he was only able to take nine steps before falling dead from the venom.

[edit] Literary sources

[edit] Eddic depictions

The two sources largest in information regarding Thor are the Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier oral tradition, and the Prose Edda, written by Snorri Sturluson. Both works are from 13th century Iceland.

[edit] Poetic Edda

- Völuspá

- Hárbarðsljóð, which details a contest between Thor and Odin in the guise of Harbarth as to who is the most accomplished.

- Grímnismál

- Hymiskviða

- Þrymskviða

- Alvíssmál

- Lokasenna

[edit] Prose Edda

[edit] Sagas

Thor is also mentioned in numerous sagas, which made use of skaldic poetry and oral traditions.

- Eyrbyggja saga

- Kjalnesinga saga

- Fóstbrœðra saga

- Fljótsdæla saga

- Hallfreðar saga

- Heimskringla

- Landnámabók

- Flateyjarbók

- Njáls saga

- Gautreks saga

[edit] Old Saxon Baptismal Vow

Thor, as Donar, is mentioned in a Old Saxon Baptismal vow in Vatican Codex pal. 577 along with Woden and Saxnot. The 8th or 9th century vow, intended for Christianizing pagans, is recorded as:

- ec forsacho allum dioboles uuercum and uuordum, Thunaer ende Uuöden ende Saxnote ende allum them unholdum the hira genötas sint

Which translates to:

- I renounce all the words and works of the devil, Thunear, Woden and Saxnôt, and all those fiends that are their associates.[3]

[edit] Gesta Danorum

In the 12th century, Saxo Grammaticus, in the service of Archbishop Absalon in Denmark, presented in his Latin language work Gesta Danorum euhemerized accounts of Thor and Odin as cunning sorcerers that, Saxo states, had fooled the people of Norway, Sweden and Denmark into their recognition as gods:

There were of old certain men versed in sorcery, Thor, namely, and Odin, and many others, who were cunning in contriving marvellous sleights; and they, winning the minds of the simple, began to claim the rank of gods. For, in particular, they ensnared Norway, Sweden and Denmark in the vainest credulity, and by prompting these lands to worship them, infected them with their imposture. The effects of their deceit spread so far, that all other men adored a sort of divine power in them, and, thinking them either gods or in league with gods, offered up solemn prayers to these inventors of sorceries, and gave to blasphemous error the honour due to religion. Some say that the gods, whom our countrymen worshipped, shared only the title with those honoured by Greece or Latium, but that, being in a manner nearly equal to them in dignity, they borrowed from them the worship as well as the name. This must be sufficient discourse upon the deities of Danish antiquity. I have expounded this briefly for the general profit, that my readers may know clearly to what worship in its heathen superstition our country has bowed the knee. (Gesta Danorum, Book I)[6]

[edit] Archaeological record

Thor was a very popular deity to the Germanic people and a number of surviving depictions of not only himself but also his exploits have survived many years of natural and intentional destruction.

[edit] Nordendorf fibula

Dating from the 7th century, the Nordendorf fibula, an (Alamannic) fibula found in Nordendorf near Augsburg (Bavaria) bears an Elder Futhark inscription mentioning Donar, the Western Germanic tribes' name for Thor.

[edit] Emblematic Mjolnir replicas

Widely popular in Scandinavia, Mjolnir replicas were used in Blóts and other sacral ceremonies, such as weddings. Many of these replicas were also found in graves and tended to be furnished with a loop, allowing them to be worn. They were most widely discovered in areas with a strong Christian influence including southern Norway, south-eastern Sweden, and Denmark.[4] By the late 10th century, increased uniformity in Mjolnir's design over previous centuries suggest it functioned as a popular accessory worn in defiance of the Christian cross.

[edit] Icelandic statue

A seated bronze statue of Thor (about 6.4 cm) from about AD 1000 was recovered at a farm near Akureyri, Iceland and is a featured display at the National Museum of Iceland. Thor is holding Mjolnir, sculpted in the typically Icelandic cross-like shape.

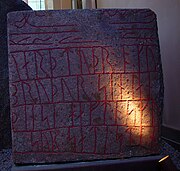

[edit] Rune and image stones

Most runestones were raised during the 11th century and so they coincided with the Christianization of Scandinavia. There are approximately six runic inscriptions that appear to refer to him and five of them do so in invocations to consecrate the stones.[7] Three of the inscriptions are found in Sweden (the Rök Runestone, Sö 140 and the Velanda Runestone) and three in Denmark (Dr 110, Dr 220 and the Glavendrup stone).[7] There are also runestones where what has been interpreted as hammers of Thor are carved.[8]

Thor's struggle with the Midgard Serpent as recorded in Hymiskviða can be found depicted on a number of image stones and runestones located in England, Denmark and Sweden respectively.

In the English village of Gosforth, Cumbria, the remains of a 10th century stone depicting Thor and Hymir fishing can be found alongside numerous other Norse carvings.[9]

In Denmark, a church in the small Northern Jutlandic town of Hørdum houses the remains of a stone featuring Thor and Hymir's fishing trip for the Midgard Serpent. Thor is wearing the distinct pointed helmet he is portrayed with in other found depictions[10] and has caught the Midgard serpent while Hymir sits before him.[11]

Sweden has two stones depicting this legend. Created sometime between the 8th and 11th centuries, the bottom left corner of the Ardre VIII stone in Gotland has often been interpreted as depicting not only the fishing trip but also references to the slaughter of the ox prior to using it as bait,[12] potentially as part of an earlier version of the tale.[13] The Altuna Runestone in Uppland depicts Thor fishing for the Midgard serpent. Though lacking Hymir, it notably displays Thor's foot breaching the floor of the boat during the intense struggle.

[edit] Canterbury Charm

The Canterbury Charm is a runic charm discovered inserted in the margin of an Anglo-Saxon manuscript from the year 1073.[14] The charm is translated as:

Cyril wound-cause, go now! You are found. May Thor bless you, lord of ogres! Gyril wound-causer. Against blood-vessel pus![14]

The charm is intended for use against a specific ailment, described as "blood-vessel pus." MacLeod and Mees (2006) note that while Thor is not revered in surviving sources for his medical abilities, he was well attested as harboring enmity towards giants and as a protector of mankind. MacLeod and Mees compare the charm to the 11th century Kvinneby amulet (where Thor is also called upon to provide protection), the formula structure of the Sigtuna amulet, and a then-recently discovered rib bone featuring a runic inscription also from Sigtuna, Sweden.[14]

[edit] Kvinneby amulet

The Kvinneby amulet is an amulet that includes a runic inscription from around A.D. 1000. There are competing theories about the exact wording of the inscription but all agree that Thor is invoked to protect with his hammer. According to Rundata, this inscription reads:

Here I carve(d) protection for you, Bófi, with/... ... ... to you is certain. And may the lightning hold all evil away from Bófi. May Þórr protect him with that hammer which came from out of the sea. Flee from evilness! You/it get/gets nothing from Bófi. The gods are under him and over him.

The amulet was found in the mid-1950s in the soil of the village Södra Kvinneby in Öland, Sweden. The amulet is a square copper object measuring approximately 5 cm on each side. Near one edge there is a small hole, presumably used for hanging it around the neck.

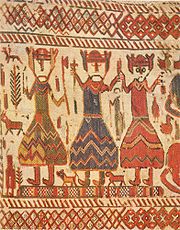

[edit] Skog Church Tapestry

A part of the Swedish 12th century Skog Church Tapestry depicts three figures often interpreted as allusions to Odin, Thor and Freyr.[15] The figures coincide with 11th century descriptions of statue arrangements recorded by Adam of Bremen at the Temple at Uppsala and written accounts of the gods during the late Viking Age. The tapestry is originally from Hälsingland, Sweden but is now housed at the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities.

[edit] Places associated with Thor

[edit] Thor's Oak

Thor's Oak was an ancient tree sacred to the Germanic tribe of the Chatti, ancestors of the Hessians, and one of the most important sacred sites of the pagan Germanic peoples. Its felling in A.D. 723 marked the beginning of the Christianization of the non-Frankish tribes of northern Germany.

The tree stood at a location near the village of Geismar, today part of the town of Fritzlar in northern Hessen, and was the main point of veneration of the Germanic deity Thor (known among the West Germanic tribes as Donar) by the Chatti and most other Germanic tribes.

[edit] Temple at Uppsala

Between 1072 and 1076, Adam of Bremen recorded in his Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum that a statue of Thor existed in the Temple at Uppsala. Adam relates that:

Thor takes the central position, with Wotan and Frey on either side. Thor, according to their beliefs, governs the air with its thunder, lightning, wind, rain, and fair weather. He is depicted carrying a scepter, much as our people depict Jove.[16]

[edit] Toponyms

As a very popular god amongst the Germanic tribes, many locations have been named after Thor:

- Thorsberg moor, Schleswig-Holstein, modern day Germany, is an ancient location bearing a large deposit of numerous ritually deposited artifacts between the 1 and 4 BC by the Angles.

- Tórshavn ("Thor's Harbor"), Faroe Islands is the capital city of the Faroe Islands.

- Thorsted ("Thor Stead"), Jutland, Denmark, near Thisted ("Tyr's Stead").

- Torsted ("Thor Stead"), Jutland, Denmark, part of Horsens Kommune.

- Thorsager ("Thor Field"), Jutland, Denmark.

- Thorskov ("Thor Forest"), Jutland, Denmark, a small, marked section of forest located directly east of the Aarhus deer park.

- Thorsø ("Thor Lake"), Jutland, Denmark.

- Thor's name appears in connection with groves (Lundr) in place names in Sweden, West Norway and Denmark.[5]

- There are a number of Anglo-Saxon place names associated with Thor in England named Þunre leah (meaning "Grove or forest clearing of thunder") such as Thundersley in Essex, England.[5]

- A "Forest of Thor" existed on the north bank of Liffey, Ireland outside of Dublin in the year 1000. It was described as destroyed over the course of a month by Brian Boru, who took particular note of the oaks.[17]

- Thurstable (Þunres Stapol or "Thor's Pillar") in Essex, England.[18]

- Thurso ("When the Norse were in Scotland they named the town after their god"), ("or Bulls water"), Caithness, Scotland

- Torhout, Belgium and Turnhout, Belgium. Both names mean "Woods of Thor".

- Hósvík (older name: Tórsvík (þ also changes into h in some Faroese words)

[edit] Thursday

Thor gave his name to the Old English day Þunresdæg, meaning the day of Þunor, known in Modern English as Thursday. Þunor is also the source of the modern word thunder.

"Thor's Day" is Þórsdagr in Old Norse, Hósdagur in Faroese, except for Suðuroy, where it's called Tórsdagur, Thursday in English, Donnerstag in German (meaning "Thunder's Day"), Donderdag in Dutch (meaning Thunder day), Torstai in Finnish, and Torsdag in Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian.

The day was considered such an important day of the week that as late as the seventh century Saint Eligius reproached his congregation in Flanders for continuing their native practice of recognizing Thursday as a holy day after their Christianization.[19]

[edit] Personal names

The name "Thor", deriving from the deity, is the first element in many names:

- English male names: Dustin, Thurston,

- English female name: Donara (from the Old High German spelling)

- Norwegian male names: Thor, Tor, Toralf, Toralv, Torbjørn, Tore, Torfinn, Torgeir, Torgils, Torgny, Torgrim, Torkel, Torkjell, Torlak, Torleif, Tormod, Torodd, Torolv, Torstein and Torvald.

- Norwegian female names: Torbjørg, Tordis, Torfrid (Turid), Torgerd, Torgunn, Torhild (Toril), Torlaug, Torunn and Torveig.

- Icelandic male names: Þór, Þórhallur, Þorbergur, Þorbjörn, Þorfinnur, Þorgeir, Þorgils, Þorgrímur, Þorkell, Þorlákur, Þorleifur, Þormóður, Þorsteinn, Þorvaldur, Þórarinn, Þórir, Þórður, Þórgnýr and Þórólfur

- Icelandic female names: Þorbjörg, Þorgerður, Þóra, Þórdís, Þórhildur, Þórunn and Þórgunnur

- Faroese male names: Hóraldur, Hórður, Hóri, Hørður, Torbergur, Torbjørn, Torbrandur, Torfinnur, Torfríður, Torgeir, Torgestur, Torgrímur, Torkil, Torleivur, Torleygur, Tormann, Tormar, Tormóður, Tormundur, Torstein, Torvaldur, Tóraldur, Tórarin, Tórálvur, Tórður, Tórhallur, Tórheðin, Tóri, Tórir, Tóroddur, Tórolvur, Tórur

- Faroese female names: Torbera, Torbjørg, Torborg, Tordis, Torfinna, Torfríð, Torgerð, Torgunn, Torgunna, Torleig, Torný, Torvør, Tóra, Tórhalla, Tórhild, Tórun(n)

- Danish male names: Tor, Torben, Torbjørn, Torkil/Terkel, Torleif, Torsten, Torvald

- Danish female names: Tora, Tove

- Swedish male names: Tor, Torbjörn, Tord, Tore, Torgny, Torkel, Torleif, Torsten, Torvald

- Swedish female names: Tora, Torunn, Tove, Tova

- Finnish male names: Torsti, Torvald

- German male names: Thorald, Thoralf/Toralf, Thorben/Torben, Thorbjörn, Thorsten/Torsten, Thorwald/Torwald

- Dutch male names: Thor/Tore, Thoralf, Thorbjörn, Thorbrand, Thorkell, Thorleif, Thorolf, Thorsten/Torsten, Thorwald/Torwald/Torvald/Torold

- Scottish name: Torquil

- English surname: Thurkettle, Thurston, Thirkell

[edit] Parallels

Many writers (Saxo, Adam of Bremen, Snorre Sturlason, Ælfric of Eynsham) identified Thor with Jupiter. The comparison can be borne: both are gods of the sky that control thunder and lightning, are children of the mother Earth, both have a son who is a god of physical strength (Hercules and Magni), and were at some time considered the most powerful of the gods. The oak tree was sacred to both gods and they had mysterious powers. Thor is to kill Jörmungandr and Jupiter, the dragon Typhon. Tacitus identified Thor with the Greco-Roman hero-god Hercules because of his force, aspect, weapon and his role as protector of the world.

Parallels with varying degrees of closeness can be found in other northern mythologies, such as Taranis (Celtic), Perkunas (Baltic), and Perun (Slavic), connected either to thunder, to oaks or to both. Additionally parallel either to Thor or Tyr are Finno-Ugric gods Torum, Thurms, Tere, Ilmarinen etc. - see Tharapita.

[edit] Portrayal in modern popular culture

Thor, under the German form of his name, "Donner" (literally, "thunder"), appears in Richard Wagner's opera cycle, Der Ring des Nibelungen. This has led to many portrayals based on Wagner's interpretation, although some are closer to pre-Wagner models. Since Wagner's time, Thor has appeared, either as himself or as the namesake of characters, in comic books, on television, in literature and in song lyrics. Thor is also written about in Amon Amarth's song 'Twilight of the Thunder God' in which he is battling Jörmungandr, with Mjolnir.

[edit] References

- ^ Styrbjarnar þáttr Svíakappa (Tale of Styrbjorn the Swedish Champion)

- ^ Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar en mesta (Greatest Saga of Olaf Tryggvason)

- ^ a b Thorpe, Benjamin. Northern mythology : comprising the principal popular traditions and superstitions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and The Netherlands (1851).

- ^ a b Turville-Petre, E.O.G. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1964. p83

- ^ a b c Ellis Davidson, H.R. Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe (1965) ISBN 0140136274

- ^ The Nine Books of the Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus, translated by Oliver Elton (Norroena Society, New York, 1905) Available online: [1]

- ^ a b Rundata 2.0

- ^ Stephens, George (1878). Thunor the Thunderer. Williams & Norgate.

- ^ Graham-Campbell, James. The Viking World (2001) ISBN 0711218005

- ^ O'Donoghue, Heather. Old Norse-Icelandic Literature: A Short Introduction (2004) ISBN 0631236260

- ^ Margrethe, Queen, Poul Kjrum, Rikke Agnete Olsen. Oldtidens Ansigt: Faces of the Past (1990), ISBN 9788774682745

- ^ Christiansen, Eric. The Norsemen in the Viking Age (2002) ISBN 0631216774

- ^ Fuglesang, Signe Horn. Iconographic traditions and models in Scandinavian imagery Available online at: [2]

- ^ a b c Macleod, Mindy. Mees, Bernard (2006). Runic Amulets and Magic Objects, page 120. Boydell Press ISBN 1843832054

- ^ Leiren, Terje I. (1999). From Pagan to Christian: The Story in the 12th-Century Tapestry of the Skog Church. Published online: http://faculty.washington.edu/leiren/vikings2.html

- ^ Adam of Bremen, Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum , book 4, sections 26-27

- ^ Carl Marstrander. Thor en Irlande, "Revue Celtique" number 36, page 247. (1915-1916)

- ^ Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England, page 27. Penn State Press ISBN 0271007699

- ^ Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology (Translated by Stallybras, 1888), IV, page 1,737. Available online through the Northvegr Foundation: [3]

[edit] See also

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Thor |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Thor |

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||