Eternal return

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Eternal return (also known as "eternal recurrence") is a concept which posits that the universe has been recurring, and will continue to recur in a self-similar form an infinite number of times. The concept has roots in ancient Egypt, and was subsequently taken up by the Pythagoreans and Stoics. In the Hebrew Scriptures, the notion is supported in the book of Ecclesiastes.[1][2][3] With the decline of antiquity and the spread of Christianity, the concept fell into disuse, though Friedrich Nietzsche resurrected it on the grounds that it provides a reason for affirming life after the decline of theism.

In addition, the philosophical concept of eternal recurrence was addressed by Arthur Schopenhauer. It is a purely physical concept, involving no "reincarnation", but the return of beings in the same bodies. Time is viewed as being not linear but cyclical.

[edit] Premise

The basic premise is that the universe is limited in extent and contains a finite amount of matter, while time is viewed as being infinite. The universe has no starting or ending state, while the matter comprising it is constantly changing its state. The number of possible changes is finite, and so sooner or later the same state will recur.

Physicists such as Stephen Hawking and J. Richard Gott have proposed models by which the (or a) universe could undergo time travel, provided the balance between mass and energy created the appropriate cosmological geometry. More philosophical concepts from physics, such as Hawking's "arrow of time", for example, discuss cosmology as proceeding up to a certain point, whereafter it undergoes a time reversal (which, as a consequence of T-symmetry, is thought to bring about a chaotic state due to entropy).

The oscillatory universe model in physics could be provided as an example of how the universe cycles through the same events infinitely.

Peter Lynds has proposed a model in which time is cyclic, and the universe repeats exactly an infinite number of times. Because it is the exact same cycle that repeats, however, it can also be interpreted as happening just once in relation to time.[4]

[edit] Indian religions

The concept of cyclical patterns is very prominent in Indian religions, including Hinduism and Buddhism among others. The Wheel of life represents an endless cycle of birth, life, and death from which one seeks liberation. In Tantric Buddhism, a wheel of time concept known as the Kalachakra expresses the idea of an endless cycle of existence and knowledge.[5]

[edit] Classical antiquity

In ancient Egypt, the scarab (or dung beetle) was viewed as a sign of eternal renewal and reemergence of life, a reminder of the life to come. (See also "Atum" and "Ma'at.")

The Christian Old Testament/Jewish Tanakh appears to make reference to the idea of recurrence in Ecclesiastes 1:9: That which has been is that which will be, And that which has been done is that which will be done. So there is nothing new under the sun.

The ancient Mayans and Aztecs also took a cyclical view of time.

In ancient Greece, the concept of eternal return was connected with Empedocles, Zeno of Citium, and Stoicism.

[edit] Renaissance

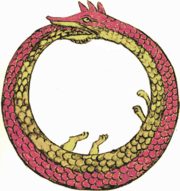

The symbol of the Ouroboros, the snake or dragon devouring its own tail, is the alchemical symbol par excellence of eternal recurrence, possibly borrowed from the Norse concept of Jörmungandr or the Midgard Serpent. The alchemist-physicians of the Renaissance and Reformation were aware of the idea of eternal recurrence; an attempt to describe eternal recurrence was made by the physician-philosopher Sir Thomas Browne in his Religio Medici of 1643:

- And in this sense, I say, the world was before the Creation, and at an end before it had a beginning; and thus was I dead before I was alive, though my grave be England, my dying place was Paradise, and Eve miscarried of me before she conceived of Cain. (R.M.Part 1:59)

[edit] Friedrich Nietzsche

The concept of "eternal recurrence" is central to the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. As Heidegger pointed out,[citation needed] Nietzsche never speaks about the reality of "eternal recurrence" itself, but about the "thought of eternal recurrence". The thought of eternal recurrence appears in a few of his works, in particular §285 and §341 of The Gay Science and then in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. It is also noted in a posthumous fragment.[6] The origin of this thought is dated by Nietzsche himself, via posthumous fragments, to August 1881, at Sils-Maria. In Ecce Homo (1888), he wrote that the thought of the eternal return as the "fundamental conception" of Thus Spoke Zarathustra.[7]

Several authors have pointed out other occurrences of this hypothesis in contemporary thought. Rudolf Steiner, who revised the first catalogue of Nietzsche's personal library in January 1896, pointed out that Nietzsche would have read something similar in Eugen Dühring's Courses on philosophy (1875), which Nietzsche readily criticized. Lou Andreas-Salomé pointed out that Nietzsche referred to ancient cyclical conceptions of time, in particular by the Pythagoreans, in the Untimely Meditations. Henri Lichtenberger and Charles Andler have pinpointed three works contemporary to Nietzsche which carried on the same hypothesis: J.G. Vogt, Die Kraft. Eine real-monistische Weltanschauung (1878), Auguste Blanqui, L'éternité par les astres (1872) and Gustave Le Bon, L'homme et les sociétés (1881). However, Gustave Le Bon is not quoted anywhere in Nietzsche's manuscripts; and Auguste Blanqui was named only in 1883. Vogt's work, on the other hand, was read by Nietzsche during this summer of 1881 in Sils-Maria.[8] Blanqui is mentioned by Albert Lange in his Geschichte des Materialismus (History of Materialism), a book closely read by Nietzsche.[9]

Walter Kaufmann suggests that Nietzsche may have encountered this idea in the works of Heinrich Heine, who once wrote:

[T]ime is infinite, but the things in time, the concrete bodies, are finite. They may indeed disperse into the smallest particles; but these particles, the atoms, have their determinate numbers, and the numbers of the configurations which, all of themselves, are formed out of them is also determinate. Now, however long a time may pass, according to the eternal laws governing the combinations of this eternal play of repetition, all configurations which have previously existed on this earth must yet meet, attract, repulse, kiss, and corrupt each other again...[10]

Nietzsche calls the idea "horrifying and paralyzing", and says that its burden is the "heaviest weight" ("das schwerste Gewicht")[11] imaginable. The wish for the eternal return of all events would mark the ultimate affirmation of life:

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: 'This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more' ... Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.' [The Gay Science, §341]

To comprehend eternal recurrence in his thought, and to not merely come to peace with it but to embrace it, requires amor fati, "love of fate":[12]

My formula for human greatness is amor fati: that one wants to have nothing different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely to bear the necessary, still less to conceal it--all idealism is mendaciousness before the necessary--but to love it.[12]

In Carl Jung's seminar on Thus Spoke Zarathustra Jung claims that the dwarf states the idea of the Eternal Return before Zarathustra finishes his argument of the Eternal Return when the dwarf says, "'Everything straight lies,' murmured the dwarf disdainfully. 'All truth is crooked, time itself is a circle.'" However, Zarathustra rebuffs the dwarf in the following paragraph, warning him against over-simplifications.

The translation of Nietzsche's eternal return is from the German ewige Wiederkunft. The German word ewige also means perpetual. Though always translated as eternal it is worth noting this potential dual meaning.

[edit] Poincaré recurrence theorem

Related to the concept of eternal return is the Poincaré recurrence theorem in mathematics. It states that a system having a finite amount of energy and confined to a finite spatial volume will, after a sufficiently long time, return to an arbitrarily small neighborhood of its initial state. It should be noted that "a sufficiently long time" could be much longer than the predicted lifetime of the universe (see 1 E19 s and more).

[edit] Arguments against eternal return

Nietzsche scholar Walter Kaufmann has described an argument originally put forward by Georg Simmel, which refutes the claim that a finite number of states must repeat within an infinite amount of time:

Even if there were exceedingly few things in a finite space in an infinite time, they would not have to repeat in the same configurations. Suppose there were three wheels of equal size, rotating on the same axis, one point marked on the circumference of each wheel, and these three points lined up in one straight line. If the second wheel rotated twice as fast as the first, and if the speed of the third wheel was 1/π of the speed of the first, the initial line-up would never recur.[13]

However, Simmel's argument may not contradict eternal recurrence. There are an infinite number of states that each wheel can occupy, but they will return to a configuration arbitrarily close to the initial one an infinite number of times, as posited by Poincaré.

[edit] References in other literature

- In modern times eternal recurrence was a major theme in the teachings of the Russian mystic P. D. Ouspensky whose novel Strange Life of Ivan Osokin (first published St. Petersburg 1915) explores the idea that even given the free-will to alter events in one's life, the same events will occur regardless. The greater part of the 11th chapter of his "A New Model of the Universe" (1914) is devoted to the idea and he there identifies allusions to eternal recurrence in the writings of Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy, Robert Louis Stevenson, Dante Gabriel Rosetti and Charles Howard Hinton.

- James Joyce was influenced by Giambattista Vico (1668-1744), an Italian philosopher who proposed a theory of cyclical history in his major work, New Science. Joyce puns on his name many times in Finnegans Wake, including the "first" sentence: "by a commodius vicus of recirculation". Vico's theory involves the recurrence of three stages of history: the age of gods, the age of heroes, and the age of humans — after which the cycle repeats itself. Finnegans Wake begins in mid-sentence, with the continuation of the book's unfinished final sentence, creating a circle whereby the novel has no true beginning or end.[14] See also Ages of Man and Greek mythology.

- The religious scholar Mircea Eliade has applied the term "eternal return" to what he sees as a universal religious belief in the ability to return to the mythical age through myth and ritual (see Eternal Return (Eliade)). Eliade's theory of "eternal return" describes a distinctly nonspontaneous process that depends on human behavior; thus, it should be distinguished from the philosophical theory of eternal return (the subject of this article), which describes a mathematically inevitable process.

- Milan Kundera's seminal work, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, is rooted in the concept of eternal return, with the narration explicitly referring to and building on Nietzsche's interpretation.

- Jorge Luis Borges, in his short story "The Doctrine of Cycles" explains and refutes the concept of the Eternal Return, citing it as being "...usually attributed to Nietzsche."[citation needed]

[edit] References in popular culture

- Sarah Brightman, in her 2008 song "Fleurs du mal" from the album Symphony, comments, "What is done will return again / Will I ever be free?"

- Woody Allen, in Hannah and Her Sisters, considers the theory of eternal recurrence. "Great", says Woody, "that means I'll have to sit through the Ice Capades again."

- At the end of the 2001 film K-PAX, the extraterrestrial named "prot" explains eternal return by scientific laws in the universe. Implying the big crunch will restart the big bang and every person and life will be lived out in exactly the same way each time this occurs.

- In the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, the polytheistic religion of the humans of the Twelve Colonies is centered on the belief of eternal recurrence, and the religious elements of the show frequently incorporate this idea with the scriptural phrase "All this has happened before, and all this will happen again." The monotheistic Cylons also adhere to this doctrine and repeat the phrase as often as the humans.[15][16]

- The first line of Disney's Peter Pan is "All of this has happened before, and it will all happen again." This line has been cited as the inspiration behind the same theme in Battlestar Galactica.

- The Information Society song, Seek200, utilizes a sample of "all of this has happened..." from a Peter Pan record, repeatedly.

- This idea plays an integral part in the story of the Xenosaga RPG trilogy, primarily near the end of the third game, Xenosaga Episode III: Also sprach Zarathustra.

- The sci-fi television series Lexx makes frequent references to this concept, and it is a relatively important plot point throughout most of the early and mid-series, including the concept of "cycles of time", and the line, "Time begins and then time ends, and then time begins once again It is happening now, it has happened before, it will surely happen again..."[17]

- The ending of Stephen King's epic magnum opus, the Dark Tower series, suggests the concept of eternal return by having the final, ultimate truth embodied at the absolute center of existence (the final door at the apex of the tower) be a trip back through time to start seeking ultimate truth (The Tower) again.

- The Rolling Stones reference the concept in their song "Sway" from the Sticky Fingers album: "Did you ever wake up to find / A day that broke up your mind / Destroyed your notion of circular time."[18]

- The idea of eternal recurrence is continually mentioned in the 2007 American horror film Wind Chill.

- Jim Morrison spoke about the idea of eternal recurrence. "Well, we’re all in the cosmic movie, you know that! That means the day you die, you gotta watch your whole life recurring eternally forever, in CinemaScope, 3-D. So you better have some good incidents happenin’ in there... and a fitting climax" - The End of "Light my Fire"(18:52) on Disc 2 of "The Doors: Live in Detroit"

- The 2007 Pulitzer Prize Winner for drama, Rabbit Hole by David Lindsay-Abaire, touches on the concept of eternal recurrence. A short story written by one of the play's characters describes a child who jumps through black holes, or rabbit holes, to access these alternate realities where his dead father is still alive.

- The Band Crosby Stills Nash and Young references the concept in the song Deja Vu with the lyrics: "If I had ever been here before on another time around the wheel I would probably know just how to deal" and "I feel Like I've been here before" and "We have all been here before"

- The plot premise of the Bill Murray movie ""Groundhog Day" is essentially modeled on the idea of eternal return.

[edit] See also

- Poincaré recurrence theorem

- Cyclical pattern

- Eternal Return (Eliade)

- Historic recurrence

- Möbius strip

- Infinite loop

- Ourobouros

[edit] Notes

- ^ Eccl. 1:9-11

- ^ Eccl. 3:15

- ^ Eccl. 6:10

- ^ Bang/Crunch/Bang. http://www.fqxi.org/community/forum/topic/111

- ^ August Thalheimer: Introduction to Dialectical Materialism from Google Cache

- ^ 1881, (11 [143])

- ^ Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, "Why I Write Such Good Books", "Thus Spoke Zarathustra", §1

- ^ See Posthumous fragment, 11 [312] 1881; See also Mazzino Montinari, Friedrich Nietzsche, 1974 (German transl. De Gruyter, 1991, French translation PUF, 2001) and also Nietzsche's personal library (see also [1] and revision of previous catalogues on the École Normale Supérieure's website)

- ^ Alfred Fouillée, "Note sur Nietzsche et Lange: le "retour éternel", in Revue philosophique de la France et de l'étranger. An. 34. Paris 1909. T. 67, S. 519-525 (French)

- ^ Kaufmann, Walter. Nietzsche; Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. 1959, page 276.

- ^ Kundera, Milan. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. 1999, page 5.

- ^ a b Dudley, Will. Hegel, Nietzsche, and Philosophy: Thinking Freedom. 2002, page 201.

- ^ Kaufmann, Walter. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. (Fourth Edition) Princeton University Press, 1974. p327

- ^ erg.ucd.ie

- ^ Battlestar Galactica: Razor - The Hybrid's Prophesy

- ^ scifi.com

- ^ Transcript for Brigadoom, 2.18 @ Wake the Dead

- ^ guitaretab.com

[edit] References

- Hatab, Lawrence J. (2005). Nietzsche's Life Sentence: Coming to Terms with Eternal Recurrence. New York : Routledge, ISBN 0-415-96758-9.

- Lorenzen, Michael. (2006). The Ideal Academic Library as Envisioned through Nietzsche's Vision of the Eternal Return. MLA Forum 5, no. 1, online at http://www.mlaforum.org/volumeV/issue1/article3.html.

- Lukacher, Ned. (1998). Time-Fetishes: The Secret History of Eternal Recurrence. Durham, N.C. : Duke University Press, ISBN 0-8223-2253-6.

- Magnus, Bernd. (1978). Nietzsche's Existential Imperative. Bloomington : Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-34062-4.

- Jung, Carl. (1988). Nietzsche's Zarathustra: Notes of the Seminar Given in 1934 - 1939 (2 Volume Set). Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691099538.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||